These churches are called cathedrals, because the bishops dwell or lie near unto the same, as bound to keep continual residence within their jurisdictions for the better oversight and governance of the same, the word being derived a cathedra – that is to say, a chair or seat where he resteth, and for the most part abideth.

— William Harrison, A Description of England, 1577

Materializing the Ephemeral

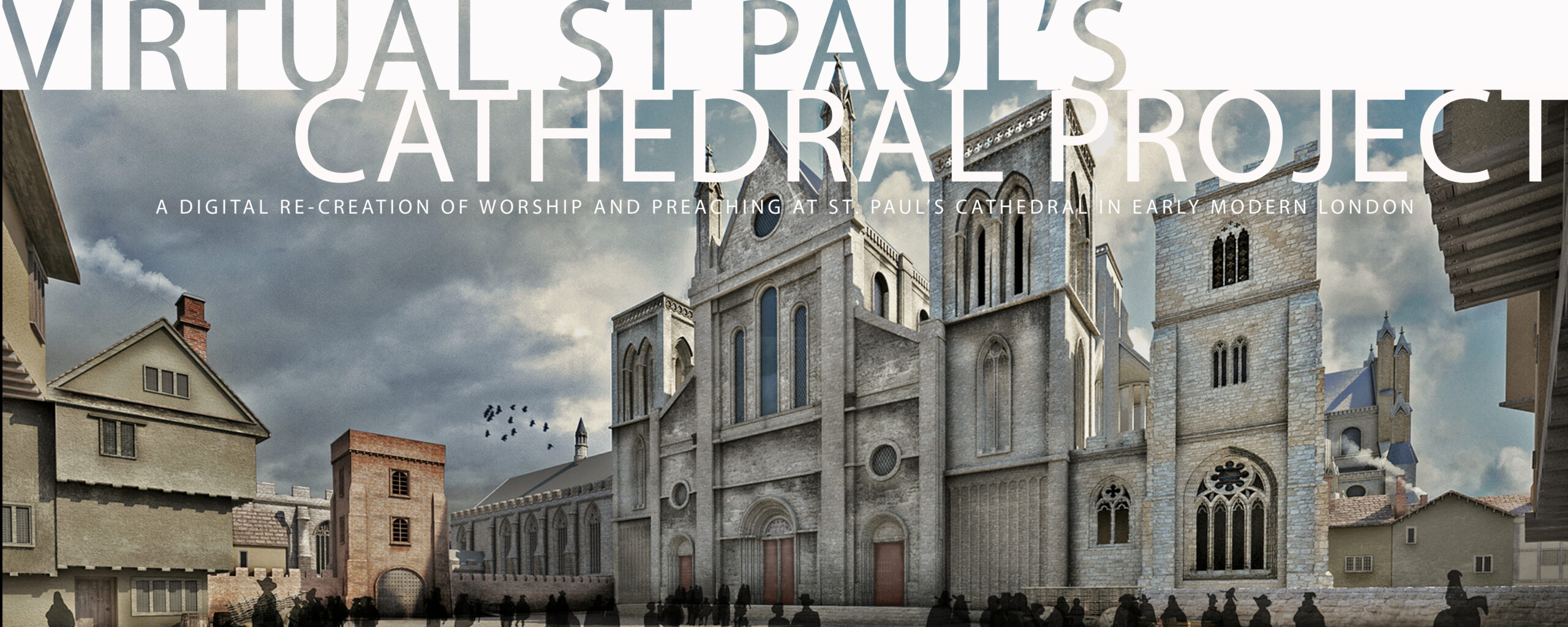

The goal of the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project is to use the tools of visual and acoustic modeling to make available to scholars the experience of public worship as scripted by the Book of Common Prayer as it unfolds in real time in a recreation of one of the most significant worship centers of the Church of England in the early seventeenth century. Our purpose is to enable scholars to study the embodied faith of the English Reformers, as opposed to the abstracted faith expressed in theological treatises. We are concerned with the experience of the performed faith, the faith that recognizes, with Jesus’ followers on the road to Emmaus, that the Risen Christ was made known to them in the breaking of the bread, made known to them in corporate action, in the joining of words and ritual actions.

In accord with the methodological principles for developing computer-based visualizations (and now auralizations) of historically significant cultural sites set forth in the London Charter for the Computer-based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage, the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project is defined as a “evidence-based restoration” of the exterior and interior of St Paul’s Cathedral and the spaces and structures of the surrounding Churchyard in the spring of 1624 and the fall of 1625.

Following the Charter’s concern for the importance of intellectual transparency in computer-based modeling and visualization of historic sites, the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project lists all research sources and seeks to clarify how the various kinds of historic materials came together to make possible what one sees and hears on this site. This includes discussions of sources for all the elements of what one sees and hears on this site, as well as assessment of the relative values of different kinds of evidence.

In addition, clear distinctions are made between those aspects of the site that 1. represent historic information, or 2. offer representative approximations of lost structures, or 3. recreate lost experiences. In the case of the latter of these aspects of the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project, the grounds for belief in the (extent of the) accuracy of approximations or recreations, as well as careful presentation of the assumptions guiding their development and realization are extensively delineated.

This approach is intended to help us to understand and evaluate our assumptions about the look and sound of the sites and sounds of worship and preaching inside St Paul’s Cathedral, adding experience in real time to our repertory of tools for interpreting these events, and – because it is flexible and open to change – to create the opportunity for testing and evaluating multiple models of the event it recreates as new information and new interpretations emerge.

Religious Context

The Church of England has always been known as a Christian tradition that emphasizes the theology of Incarnation, the recognition of the divine in space, time, and human action. While most scholars of the English Reformation and its aftermath have emphasized theology as concerned with the real of ideas, the word spoken or printed, the formal, logical abstractions of verbal formulation, the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project has been designed to enable us to experience thus reflect upon worship and preaching at St Paul’s Cathedral as events that unfold over time and on particular occasions in London in the early seventeenth century. Such events underscore how the post-Reformation Church of England placed corporate worship at the center of its religious identity. Enabled by Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer, “one use” for all England, worshippers prayed in “one voice,” sought assurance of their faith in their public works of charity to one another, and were assured that their hope lay in being part of one “mysticall body.”

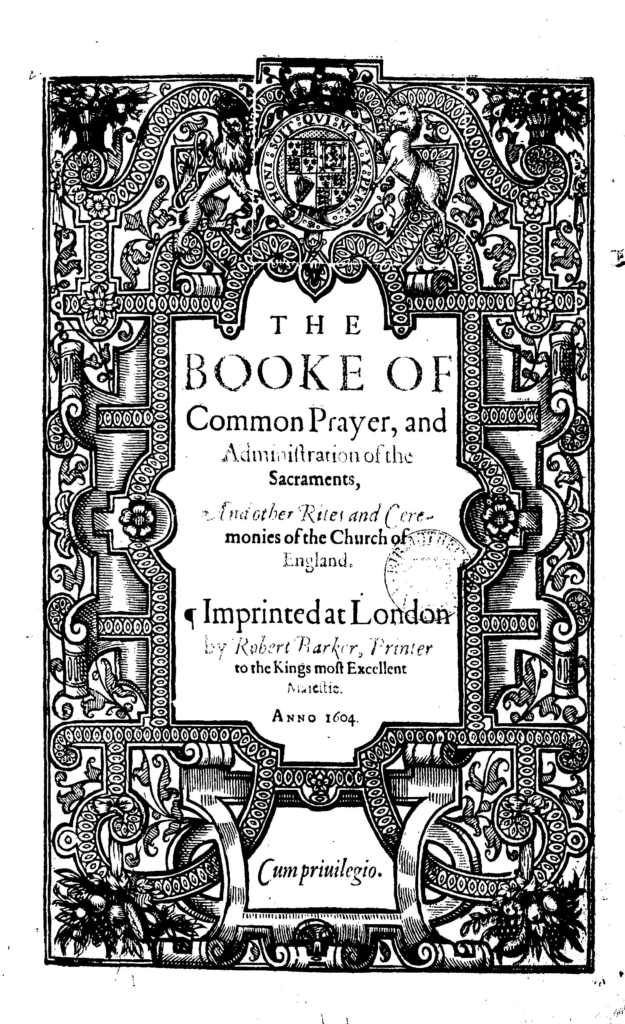

As a result of its central place in the public religious life of England, the Book ofCommon Prayer was one of the most frequently-reprinted books in early modern England. Yet our understanding of it is complicated by the artificial separation we make between the Prayer Book as a book and the Prayer Book in practice. The Prayer Book, in and of itself, is not what matters; all the Prayer Book does is to provide rituals, scripts, for the corporate worship it enables. What matters is the worship of the gathered community itself, the embodiment of the Church as the Body of Christ.

Lived Religion

We hope that by using the St Paul’s Cathedral Project, students of the English Reformation will shift their attention from debates among academic theologians, however interesting they may be, to the lived experience of corporate worship and to the formation in Christian living it encourages.

Our concern is, therefore, with what Peter Verhagen and others have called “lived religion.”11 As Timothy Rosendale and Daniel Swift have both recently pointed out,2 the Book of Common Prayer has not received the attention it deserves from historians and literary scholars, who have attended more fully to the history of Bible translation and to the theological disputes among the Reformers.

Nonetheless, both Rosendale and Swift underestimate, and mostly ignore, the work of their predecessors, especially Thomas Stroup,3 on the parallels between the structure of Prayer Book rites and plays by Shakespeare, on the parallels between the structure of Prayer Book rites and Spenser’s Amoretti and the Art of the liturgy,”4 on echoes of the Psalms and scripture readings as received through the Prayer Book lectionary in Spenser’s Amoretti, or Ramie Targoff’s discussions of prayer as performance,5 or my own work on the influence of the Book of Common Prayer on the work of Spenser, Donne, Herbert, and Vaughan.6

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project and its companion the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project remind us that the early modern sermon is primarily an act of performance, conducted in the relationship between priest and congregation on a specific occasion and in a specific architectural setting. To understand more fully the surviving texts of early modern sermons, we are called to situate them in reconstructions of their original setting, recognizing that the texts that survive represent, at best, scripts for their performance and, more commonly, only provide traces of the lost original.

If the commonly-held belief that early modern preachers worked from notes rather than fully-developed texts is true, then the distance between the sermon delivered and the sermon text either in manuscript or printed form is marked by issues of memory, after-the-fact second thoughts, and expansions of the text. This point is reinforced by the large number of clergy who refused to have their sermons printed on the grounds that something essential to their understanding of a sermon when it was removed from the specific context of its delivery and isolated on the printed page. We are also called to recognize that part of the context for every sermon is the matrix of biblical texts appointed for public reading on that day by the lectionaries of the Book of Common Prayer.

- See Verhagen’s essay here: https://www.academia.edu/69181344/Lived_Religion_Proposal_for_a_new_congenial_definition.

- See Rosendale’s Liturgy and Literature in the Making of Protestant England (Cambridge, 2007) and Swift’s Shakespeare’s Common Prayers: The Book of Common Prayer and the Elizabethan Age (Oxford, 2013).

- See Stroup’s Microcosmos: The Shape of the Elizabethan Play (Kentucky, 1965).

- In SEL 1974, pp 47-61.

- Ramie Targoff, Common Prayer: The Language of Public Devotion in Early Modern England (Chicago, 2001).

- John N. Wall,Transformations of the Word: Spenser, Herbert, Vaughan [Georgia, 1988), also “John Donne and the Practice of Priesthood.” Renaissance Papers 2007 (2008), 1-16.

Quick Access to the Cathedral Project

Quick Access to Sound Changes

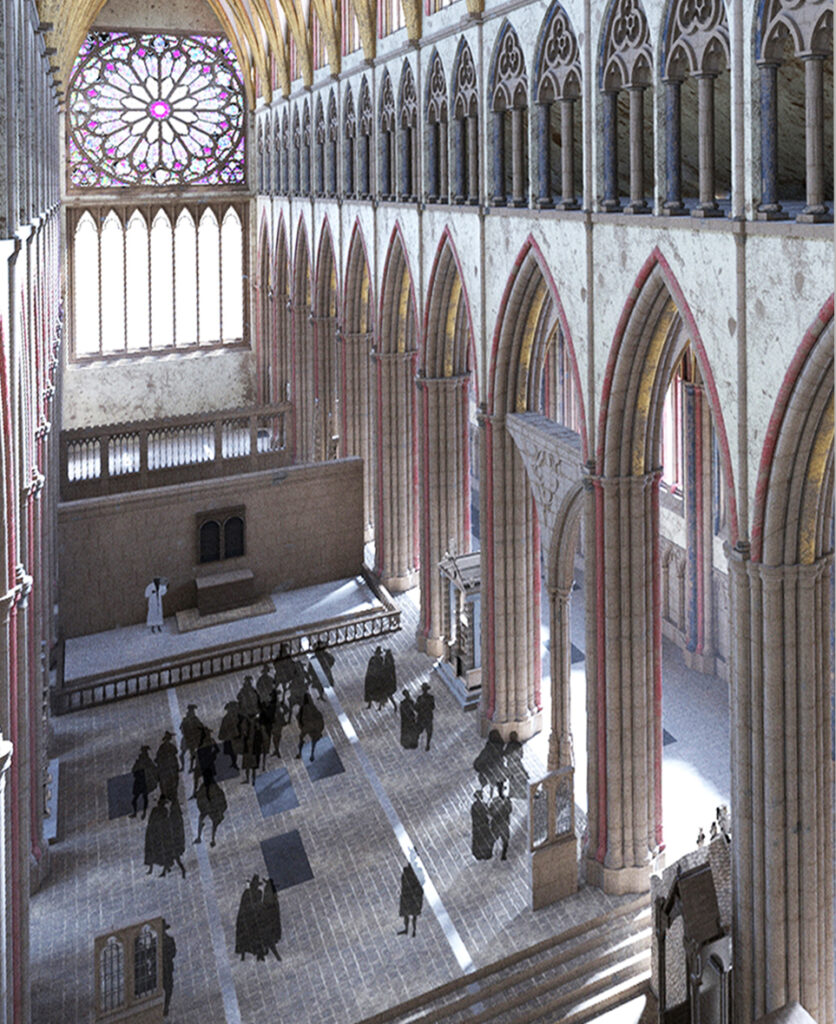

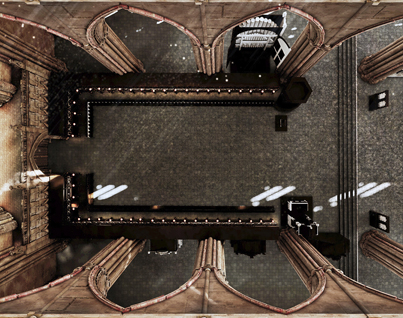

Thanks to auralization of sound within our acoustic model of St Paul’s Choir, we can experience differences in the sound of worship services as we move from one part of the Choir to another. We chose five specific listening positions as the basis of our acoustic modeling. Each of the worship services recreated on the website can be heard in full from each of these five listening positions. To sample the experience of sound as it changes in volume and sound quality as one moves about the space from one of these listening positions to another, click on the image below. This video is about 2 minutes long and moves us from one of these listening positions to another as we listen to the beginning of our recreation of the service of Matins on Easter Sunday 1624.

Prayer Book Worship

Each occasion of worship scripted by the Book of Common Prayer brings to life a moment of intersection between the gathered worshiping community and the cycles of Biblical reading, prayer, and sacramental enactment. By experiencing our recreations of some of these acts — of reading, of prayer, of preaching, of hearing and responding, of sacramental participation — we may be able to glimpse the religious life of early modern England in process. At the least, we may come to know what went into preparing for these events, who was needed for them to be performed, and what might be the outcome of participating in the ordered public life of a post-Reformation Church that had reimagined itself as essentially pragmatic, as essentially corporate, liturgical, and sacramental.

The worship practices of the gathered community provided the context, and the vehicle, for understanding Christian faith, developing religious identity, and practicing the vocabulary of belief. Sundays in cathedrals and collegiate and parish churches saw the people of God gathered for Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, and Holy Communion with sermon, followed in the afternoon by Evening Prayer, perhaps including catechizing or another sermon. Each weekday, clergy, either alone or with members of their flocks, continued the reading of Morning and Evening Prayer.

By the time John Donne became Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in 1621, the Church of England defined by the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) had been in place for six decades. Several generations of Englishfolk had been baptized, confirmed, participated in worship services, received Holy Communion, married, ministered to in sickness, and buried through use of the Prayer Book rites. Texts and language that were new in 1549 or 1552 or 1559 had become familiar, their recitation habitual, their rhythms dependable structuring elements in their daily lives, their rites giving meaning to the significant moments in their individual lives through incorporation into the public worship of the gathered community.

Over the course of a lifetime, Englishfolk were formed as post-Reformation Christians and developed their understanding of the faith through their corporate practice. Assured that their children were, through Baptism, “regenerate and graffed into the bodye of Christes congregacion,” assured at Holy Communion that they were “very membres incorporate in thy mistical body, whiche is the blessed company of al faithful people, and . . . heyres through hope of thy everlasting kingdom,” assured at funerals that their deceased loved ones were buried in “sure, and certein hope of resurrection to eternall lyfe,” assured three times during every Sunday’s services that they had received “mercy,” “pardon,” and “absolution” from their sins, been confirmed and strengthened “in all goodness,” and advanced on the way “to everlasting life,” they were constantly being affirmed, informed, and supported in their Christian journeys. 1

Performance of these interactive and community-building rites of public corporate worship, scripted by the Book of Common Prayer, enabled the nation, gathered in prayer, to join in unison in its address to God, be assured that their sins were forgiven, find support in times of trial, and affirmation that they were “fulfilled with [God’s] grace and heavenly benediction.“2. As a result of this general implementation of Cranmer’s plan for the transformation of corporate religious life in England, what had been new and strikingly different in 1549, or 1552, or even 1559 had become customary, expected, and reassuring. As Eamon Duffey has put it, “Cranmer’s somberely magnificent prose, read week by week, entered and possessed their minds, and became the fabric of their prayer, the utterance of their most solemn and their most vulnerable moments.”3

Setting

We locate our recreation of the rites of the Book of Common Prayer in the Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral in London in the 1620’s, during the tenure of John Donne as Dean of the Cathedral. Our interest in specific physical spaces is as deliberate as our interest in the rites of public worship because they define what people see when they gather, and how well they can hear, and what distractions they might encounter. Worship scripted by the Book of Common Prayer is always embodied worship, taking place in specific sites, with specific gatherings of people, and on specific occasions in the Church Year and in the individual and corporate lives of the clergy and their congregations.

The St Paul’s Cathedral Project enables us to explore how — through use of the Prayer Book — the Bible was received and the parishioners’ relationships with God were negotiated through public worship, the public performances of lectionary readings, preaching from biblical texts, and performance of biblically-derived Prayer Book liturgies. In these worship services, parishioners were no longer passive observers of rites performed in Latin by clergy, but were active participants in these rites, joining in corporate confession, recitation of the Lord’s Prayer and the Creeds, and reception of the bread and wine of Holy Communion. They heard the Bible read sequentially, year after year. They watched the Seasons of the Church Year bring them through fasts and festivals, through the annual remembrance of Jesus’ life and the Church’s reflection on its calling as the Body of Christ.

To make it possible to understand the full experience of corporate public worship in the post-Reformation Church of England, the Cathedral Project recreates worship services from the Book of Common Prayer (1604) on two representative days in the Church of England’s liturgical calendar. The central event is a recreation of worship for Easter Sunday, March 28th, 1624, a festival occasion. The day begins with Sung Matins, continues with the Great Litany and Holy Communion, including Bishop Lancelot Andrewes’ sermon for that day, then concludes with Evensong and the sermon John Donne, Dean of the Cathedral, preached at the cathedral on that day in 1624.

The second day of services is for the Tuesday after the First Sunday in Advent in 1625, an ordinary (or ferial) day on the calendar of the Church of England, a day defined only by the observation of Matins and Evensong. These services are set within a detailed model of the cathedral itself, as well as the buildings and spaces that surrounded it in Paul’s Churchyard, as they were until they were all swept away by the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Personnel

We focus attention on John Donne, the English poet and essayist who was born into a Roman Catholic family but who became a priest of the Church of England in 1615 and served as Dean of St Paul’s from 1621 until his death in 1631. More famous for his poetry, Donne also preached dozens of sermons in his lifetime, creating a body of religious prose that dwarfs the scale of his secular writings. 4

Donne became a priest of the Church of England in 1615, nearly 60 years after the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) had established the basic institutions, structures of authority, ceremonial practices, and beliefs of the reformed Church. The Elizabethan Settlement had survived the challenges of those who believed it was insufficiently reformed, as well as the uncertainties posed by the transition from the reign of Elizabeth I to the reign of James I. The Elizabethan Settlement had been reaffirmed by the Hampton Court Conference of 1604. It, along with James I, had escaped the potentially catastrophic aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

By the time Donne became Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in 1621, the religious life of England had had six decades of public worship and spiritual formation enabled by use of the Book of Common Prayer. Language and practices that in the early 1560’s were startlingly new had become familiar and habitual. In addition, by 1621, especially in cathedrals like St Paul’s, the English choral tradition had also made the transition from Latin to English as new generations of singers and musicians had discovered ways of enriching Prayer Book worship through choral settings of Prayer Book canticles and other texts as well as through anthems based on biblical texts.

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project enables us to experience in real time the daily and weekly worship life of the Church of England from within the rites of worship themselves as they unfold through the hours of their performance. Unlike studies of the post-Reformation Church of England that emphasize theological debates and formularies of belief, the Virtual Cathedral Project immerses us in the lived experience of worship.

While most scholars want to identify and define the post-Reformation Church of England as fixed at a paradigmatic moment in its development, the Virtual Cathedral Project enables us to recognize that what characterized the Church of England was a continuity of practice over time. This practice would be interpreted in a variety of ways, as theological perspectives and reflection on the experience of worship changed with the passage of time. The practice of worship itself could change, as styles of ceremonial, vestments, and performance changed. But the core rites and processes of Biblical readings, prayers, sacraments, and preaching remained the same. The structure of the Daily Offices and Holy Communion remained the same. The mix of continuity and difference between the post-Reformation Church of England and its medieval predecessor ebbed and flowed, but the central practices and texts of Cranmer’s early Prayer Books remained the same.

After all, even after the Civil War, and the Restoration of the Church of England, and after the 19th century flourishing of evangelicalism under the Wesleys and the flourishing of catholic worship post-Oxford Movement, the official worship text and the core worship life of the Church of England remains the Prayer Book of 1559, in its lightly-revised version of 1662.

More Shortcuts to Exploring the Cathedral Project

https://www.academia.edu/69181344/Lived_Religion_Proposal_for_a_new_congenial_definition.

- Quotations from the Book of Common Prayer (London, 1604), Robert Barker, Printer. STC 1627.

- BCP, Holy Communion, Post-Communion Prayer.

- Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in Englandc. 1400–1580. London: Yale University Press, 1992, p. 589.

- Details of Donne’s life are chiefly drawn from R. C Bald’s John Donne: A Life (Oxford, 1970), still the most important biography of Donne, after all these years.