WHERE at the death of oure late Soveraigne lord King Edward the sixt, there remained one uniforme order of common service and prayer, and of the administracion of Sacramentes, Rites, and Ceremonies, in the churche of Englande, whiche was set furth in one booke entituled: The booke of common prayer, and administracion of Sacramentes, and other Rites and ceremonies in the churche of Englande, aucthorised by Act of Parliament . . .

Be it therefore enacted, by the aucthoritie of this present parliament, that the sayde booke, with the ordre of service, and of the administracion of Sacramentes, Rites and Ceremonies, with the alteracion, and addicions, therein added and appoynted by this estatute, shall stande, and be from and after the sayde feaste of the Nativitie of Sainct John Baptist, in full force and effect . . .

And further be it enacted by the quenes highnes, with the assent of the lordes and commons, in thys present Parliament assembled, and by aucthoritie of the same, that all and synguler ministers, in any cathedrall, or paryshe church . . . shall . . . be bounden to saye and use the Matins, Evensong, celebracion of the Lordes supper, and administracion of eche of the Sacramentes, and all their Common and open prayer, in suche ordre and fourme, as is mencioned in the sayde booke . . . . .

From An Act for the Vniformitie of Common Prayer, and Service in the Church, and administration of the Sacraments (The Act of Uniformity, 1559)

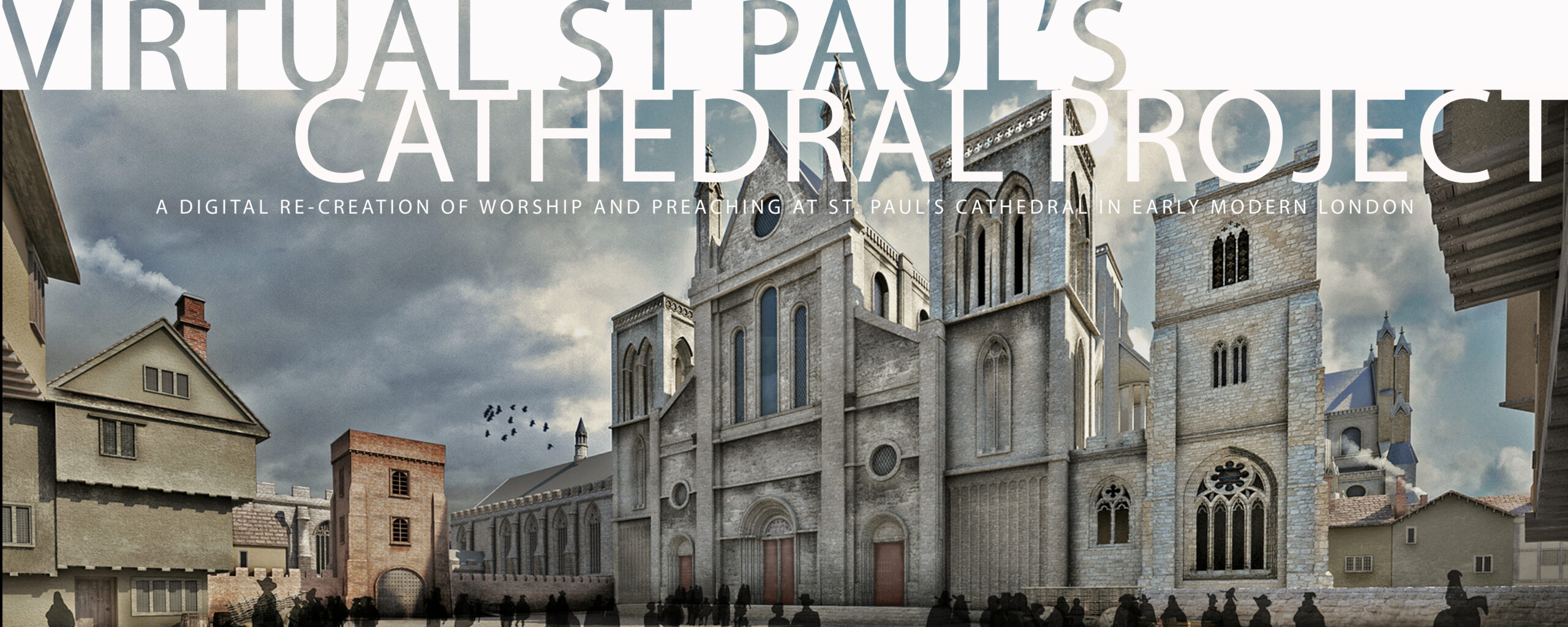

Worship at St Paul’s Cathedral

The purpose of this section of the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral website is to set out the assumptions about worship in the Church of England in the years between the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion in 1559 and the outbreak of the English Civil War in the early 1640’s that have guided us in recreating worship services at St Paul’s. Our goal here is to clarify the role of cathedrals in the post-Reformation Church of England, to identify some of the continuities and discontinuities between worship pre- and post-Reformation, to explore how the Book of Common Prayer structures the intersection of prayers, scripture readings, choral performances, and sacramental acts that constituted daily worship in cathedrals and collegiate churches and, we believe, in the majority of chapels and parish churches across England in the early modern period.

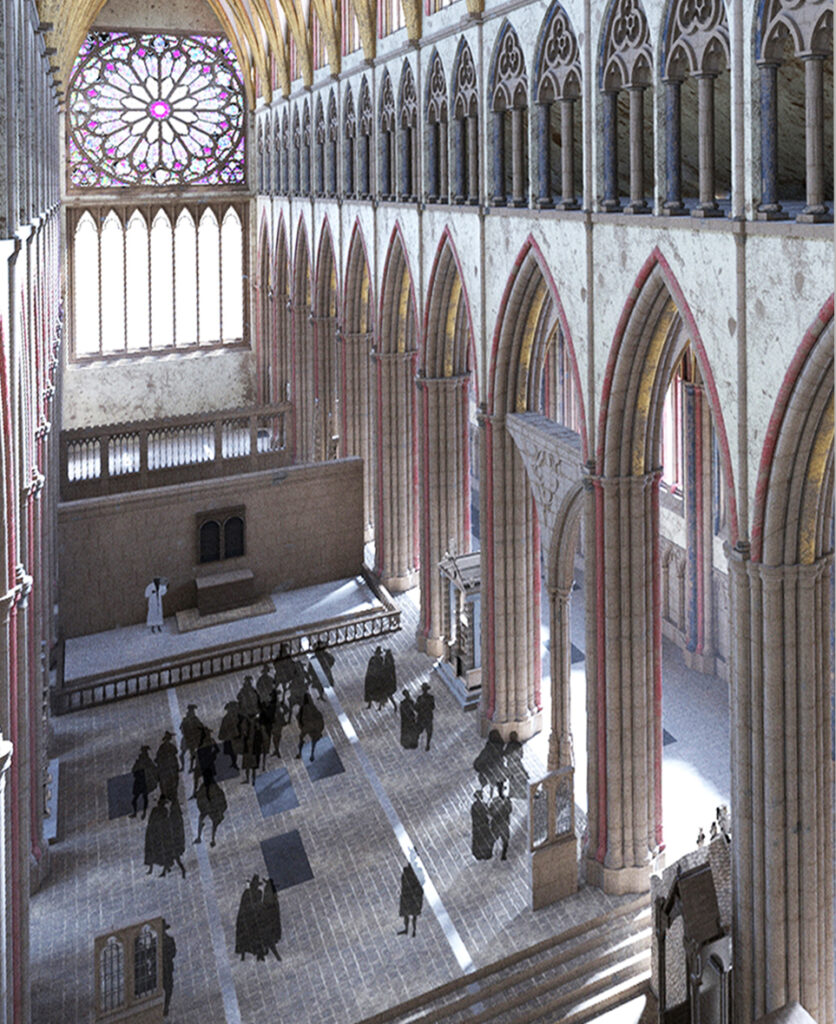

The chief function of a cathedral in early modern England was to maintain the daily round of worship services according to the use of the Book of Common Prayer. Maintaining the daily round of worship was, to quote from the Book of Common Prayer, the “bounded duty and service” of the Cathedral’s staff. In the words of Roger Bowers, our consultant on everything musical, “those attending to the efforts of the earthly choir below were the denizens of the heavenly choir above, and that sufficed. Just as in pre-Reformation times, each service was an act of worship addressed to the Almighty, to the other Persons of the Trinity, and to all the hosts of heaven, all offered up in a manner designed also to edify and sanctify those on Earth by whom it was being performed. Whether or not any other mere human was present to hear was a matter of entire irrelevance.” There surely were days when no one except the members of the Cathedral’s Choir and its clergy were present, but from the perspective of the cathedral and its staff, that did nto matter.

Cathedral clergy and musicians maintained this daily round as an end in itself, as the material embodiment of the diocese at prayer, and as a model of devotion and practice for other churches in the diocese. Worship in St Paul’s Cathedral was a manifestation and embodiment of the entire Diocese of London collectively hearing God’s Word, taking part in God’s sacraments, and offering to God the world in its brokenness for God’s healing. Worship at St Paul’s and other cathedrals in each diocese of the Church of England therefore served as an example, a standard, and a surrogate for parish churches in their own embodiment of this prescribed round of services. The style of cathedral worship was distinctive, with its use of organ and a professional choir of men and boys, but the services themselves were the same.

Our recreations of worship in the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project are based on the assumption that the requirements for worship in the Church of England, as set out in the Book of Common Prayer (1559 and 1604) and in the Act of Uniformity of 1559, and which were reinforced by the Canons of 1604, were followed in cathedrals and the vast majority of parish and collegiate churches across England. English law required citizens to attend worship in their local parish churches, to have their new-born children baptized in this churches within a few days of birth, and to have the major events of their lives, from marriage to burial, organized and informed by use of the texts of the Book of Common Prayer. Through the performance of these rites, the private became public, the community was formed, sustained, and identified as the People of God, and, as William Harrison put it, the community recognized itself as Church, as God’s people, through their act of pouring “out their petitions unto the living God for the whole estate of His church in most earnest and fervent manner.”

While opposition by some clergy and laity to use of the set prayers, formal liturgies, and liturgical calendars of seasons and biblical readings set out in the Book of Common Prayer is well-documented, so, too, is lay resistance to clergy who insisted that the Prayer Book remained too Catholic and needed further purification on scriptural models. [1] For the vast majority of the English in the post-Reformation period, however, their understanding of their faith was formed by what they experienced in worship scripted by the Prayer Book and were told about the meaning of that experience by the texts of the Prayer Book in their explanations of the meaning of participation in the Church’s public acts of worship. For the reluctant or the disagreeable, the system of fines imposed by the Act of Uniformity for people who refused to attend Prayer Book worship on Sundays in their local parish churches, as well as other requirements concerning baptisms, marriages, and thrice-annual reception of Holy Communion, must have ensured that the local parish church and the cycles of services conducted there were familiar to almost everyone.

Corporate, Liturgical, and Sacramental

The genre of the Book of Common Prayer is, of course, the Regulum, or Rule of St Benedict, [1]See Martin Thornton, English Spirituality (1963, a spiritual and theological tradition that, in the words of Harvey Guthrie, “makes it possible for the basis of the spiritual life of a community of Christian people to be the corporate, liturgical, sacramental, and domestic life of that community itself.” The Prayer Book’s rites enable the gathered community of believers to be formed, enabled, assured, and supported by their participation in the rites of the Book of Common Prayer.

A Pragmatic Universalism[2]For a discussion of Richard Hooker’s “hypothetical universalism,” see Michael J. Lynch. “Richard Hooker and the Development of English Hypothetical Universalism,” in … Continue reading

Participation in the worship of the Church of England provided layfolk with membership in a body that welcomed them and supported them communally through the most important transitions in their personal lives, from birth to coming of age to marriage to illness and finally to their deaths. What mattered to most folks who took part in its public ceremonies was that those ceremonies were meaningful and effective, providing reassurance of their membership in “the blessed company of all faithful people.”

The rites of the Prayer Book created for ordinary parishioners provided, in the words of David Bagchi, “a daily and weekly framework of comfort and assurance.”[2] As their lives were shaped and informed by participation in the community of worship scripted by the Prayer Book rites, they were constantly being affirmed, informed, and supported in their Christian journey.[3] Among the things they were taught was happening as they participated in the rhythm of the Daily Offices, received the sacraments of Baptism and Holy Communion, and were baptized, confimed, married, and buried according to the Prayer book rites, are the following:

- At every service of Holy Communion, they were reminded that the model for the Christian life they were called to live was a life in community, a life described as consisting of repenting of one’s sins, of being “in love and charitie with your neighbors,” of intending “to lede a newe lyfe, following the commaundementes of God and walkynge from hence furthe in his holy waies,” and of drawing “nere and tak[ing] this holy Sacrament (of corporate Communion) to your comfort,” a process now (re)begun by participating in a public act of repentance and of receiving the priest’s pronouncement of God’s promise to have “mercye upon you, pardon and deliver you from all your sinnes, confirme and strengthen you in all goodnes, and bring you to everlastyng lyfe.” So the priest invites the faithful to “make your humble confession to almighty God, before this congregation here gathered together in his holye name, mekely knelynge upon your knees.”

- Their children (and they, by inference) had been “embraced” by God in the rite of Baptism “with the arms of his mercy,” had been given “the blessing of eternal life,” and were, through baptism, “regenerate and graffed into the bodye of Christes congregacion.”

- They were assured when confirmed by their Bishop that God would “strengthen them . . . with the Holy Ghost the Comforter, and daily encrease in them [God’s] manifolde gifts of grace.”

- They were taught at weddings that their marriage signified “the mystical union that is betwixt Christ and his Church.”

- Weekly — or at least three times a year — they were assured at Holy Communion that they who had “duly received these holy mysteries” were “blessed members incorporate in the mystical Body of thy Sonne, which is the Blessed Company of all faithful people” and were “heyres through hope of thy everlasting kingdom.”

- They were assured at funerals that their deceased loved ones were buried in “sure, and certein hope of resurrection to eternall lyfe.”

- Those who had received the Last Rites of the Church were taught that they approached their deaths forgiven for their offences, absolved “from al [their] synnes,” and abided “in sure and certain hope of resurrection to eternall lyfe.”

- Three times during every Sunday’s services, and daily if they took part in the Daily Offices, they were assured that they had received “mercy,” “pardon,” and “absolution” from their sins, been confirmed and strengthened “in all goodness,” and advanced on the way “to everlasting life.”

Contrary to the claims of many historians that the theology of the reformed Church of England was essentially Calvinist,[1] and in contrast to the bleak pessimism of Archbishop Whitgift’s Lambeth Articles,[3]Hence convinced that one’s status before God depended on God’s eternal decree regarding someone rather than on any temporal event in which that person might participate; for how the history of … Continue reading with its division of God’s people into the damned and those whom God had chosen to save from before all time, certainly before anyone living in England in the 1620’s had a chance to have a say in the matter, the Book of Common Prayer embodied and enabled a theology of pragmatic universalism.

The Prayer Book’s consistent message to all parishioners is that by virtue of their participation in corporate worship scripted by the Prayer Book and by fulfilling in their “new lives” the guidance to “repent,” to “live in love and charity with their neighbors,” to follow “the commaundementes of God and walkynge from hence furthe in his holy waies,” they could live, from their births to their deaths, in “sure and certain hope” that they were reconciled to each other and to God and thus were “heyres through hope of thy everlasting kingdom.” Or, again to quote John Donne, this time at Easter of 1627, preaching in the Choir of St Paul’s, “This is the faith that sustaines me, when I lose by the death of others, or when I suffer by living in misery my selfe, That the dead, and we, are now all in one Church, and at the resurrection, shall be all in one Quire.” [4]For discussions of the Prayer Book’s role as a component of Thomas Cranmer’s broader Reform program of social transformation of England into the true Christian Commonwealth which Cranmer … Continue reading

The Prayer Book’s pragmatic emphasis on the outward, corporate, and communal in its staging of the way to the true Christian commonwealth in this life and to salvation in the next is reflected in the Church of England’s official statement of belief the (originally Forty-Two in 1553 but by 1571) Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion. Article 17 refers to the newly invigorated concept of predestination among continental Reformers, not as a statement of belief but as a pastoral concept stands in stark contrast to the obsessive inward-turning emphasis of Calvin’s followers. In this presentation, the positive side of predestination theology is good to talk about because it is “full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort to godly persons” because it “doth greatly establish and confirm their faith” and “kindle their love of God.” The other side of classic predestinarian thought, however, is “a most dangerous downfall,” leading to desperation, or into a recklessness of most unclean living,” and therefore should not be mentioned again.

Outward and Corporate

In the Preface to the first Book of Common Prayer (1549), Archbishop Cranmer stresses the importance of uniform public worship, noting that heretofore, there hath been great diversitie in saying and synging in churches within this realme: some folowyng Salsbury use, some Herford use, some the use of Bangor, some of Yorke, and some of Lincolne: Now from hencefurth, all the whole realme shall have but one use.[5]See Judith Maltby, Prayer Book and People in Elizabethan and early Stuart England (Cambridge, 1998) for an informed discussion of the limits on implementation of the English liturgical … Continue reading Cranmer’s vision is of a nation united in prayer through “use” of common forms of worship and texts for prayer. To enable this uniformity of worship, the Church of England in the reign of Edward VI, produced a series of monumental publications stretching from the Great Bible (1539), [6]William Harrison, The Description of England (second edition 1587; rpt. Dover, 1968) p. 36. through the first Book of Homilies (1547) and the first Books of Common Prayer (1549, 1552), investing enormous resources in enabling Englishfolk to have “one use”

As a result of the general implementation of Cranmer’s plan for the transformation of corporate religious life in England, as Eamon Duffey puts it, “Cranmer’s somberely magnificent prose, read week by week, entered and possessed their minds, and became the fabric of their prayer, the utterance of their most solemn and their most vulnerable moments.” [7]In The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, c. 1400 – c. 1580, second edition (Yale, 2005) p. 593 Or, as William Harrison put it in his classic contemporary account of Tudor social life [8]In The Description of England (1587, rpt. ed Georges Edelen, Dover Publications (New York1968), “the minister saith his service commonly in the body of the church, with his face toward the people” so “the ignorant doo not onelie learne diuerse of the psalmes and vsuall praiers by heart, but also such as can read, doo praie togither with [the priest]: so that the whole congregation at one instant powere out their petitions vnto the liuing God.”

There is nothing read in our churches but the canonical Scriptures, whereby it cometh to pass that the Psalter is said over once in thirty days, the New Testament four times, and the Old Testament once in the year. And hereunto, if the curate be adjudged by the bishop or his deputies sufficiently instructed in the holy Scriptures, and therewithal able to teach, he permitteth him to make some exposition or exhortation in his parish unto amendment of life.

And for so much as our churches and universities have been so spoiled in time of error, as there cannot yet be had such number of able pastors as may suffice for every parish to have one, therebare (beside four sermons appointed by public order in the year) certain sermons or homilies (devised by sundry learned men, confirmed for sound doctrine by consent of the divines, and public authority of the prince), and those appointed to be read by the curates of mean understanding (which homilies do comprehend the principal parts of Christian doctrine, as of original sin, of justification by faith, of charity, and such like) upon the Sabbath days unto the congregation.

And, after a certain number of psalms read, which are limited according to the dates of the month, for morning and evening prayer we have two lessons, whereof the first is taken out of the Old Testament, the second out of the New; and of these latter, that in the morning is out of the Gospels, the other in the afternoon out of some one of the Epistles.

After morning prayer also, we have the Litany and suffrages, an invocation in mine opinion not devised without the great assistance of the Spirit of God, although many curious mind-sick persons utterly condemn it as superstitious, and savouring of conjuration and sorcery. This being done, we proceed unto the communion, if any communicants be to receive the Eucharist; if not, we read the Decalogue, Epistle, and Gospel, with the Nicene Creed (of some in derision called the “dry communion”), and then proceed unto an homily or sermon, which hath a psalm before and after it, and finally unto the baptism of such infants as on every Sabbath day (if occasion so require) are brought unto the churches; and thus is the forenoon bestowed. In the afternoon likewise we meet again, and, after the psalms and lessons ended, we have commonly a sermon, or at the leastwise our youth catechised by the space of an hour.

And thus do we spend the Sabbath day in good and godly exercises, all done in our vulgar tongue, that each one present may hear and understand the same, which also in cathedral and collegiate churches is so ordered that the psalms only are sung by note, the rest being read (as in common parish churches) by the minister with a loud voice, saving that in the administration of the communion the choir singeth the answers, the creed, and sundry other things appointed, but in so plain, I say, and distinct manner that each one present may understand what they sing, every word having but one note, though the whole harmony consist of many parts, and those very cunningly set by the skilful in that science.

For these rites, the Lectionaries of the Book of Common Prayer organized the transmission of the Bible from page to people in a structured order, so that — through reading out loud in the context of the daily services of Morning and Evening Prayer — the Old Testament was read through once a year and the New Testament was read through three times a year. Additional readings from Scripture were provided for celebrations of Holy Communion on Sundays and Holy Days.

Vestments

Continuities and Discontinuities in Vestments

The apparel in like sort of our clergymen is comely, and, in truth, more decent than ever it was in the popish church . . . . . William Harrison, A Description of England (1577)

One of the many marks of continuity between the post-Reformation and pre-Reformation Church of England was the continuation of medieval Choir dress for clergy, consisting of cassock, surplice, and tippet, with a Canterbury cap upon one’s head, as the standard attire for conducting (non-eucharistic) worship services.

Below are a pair of English martyrs wearing the same clerical attire of cassock, surplice, and tippet, as well as the Canterbury cap. One the left is John Fisher, beheaded on Tower Hill on June 22, 1535 for refusing to acknowledge Henry VIII as Supreme Head of the Church in England. On the right is Nicholas Ridley, burned at the stake, along with Hugh Latimer, in Oxford on October 16, 1555 for refusing to acknowledge the Pope as the Head of the Church in England.

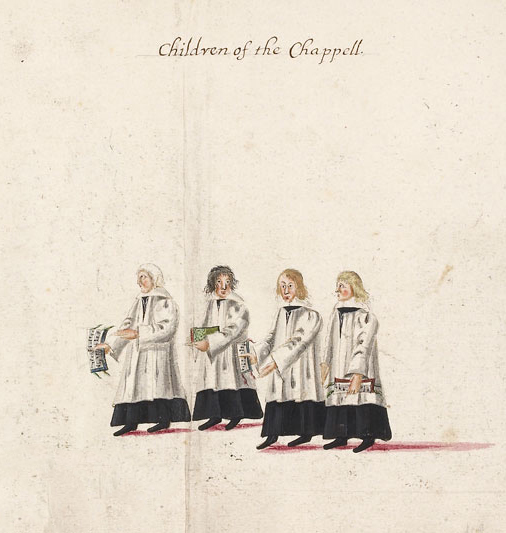

The wearing of cassocks and surplices also extended from the clergy to members of the Choir. The image below, from the unique color drawing of Queen Elizabeth I’s funeral procession, shows some of the Choristers from the Chapel Royal wearing their cassocks and surplices, a practice surely duplicated at St Paul’s Cathedral.

The wearing of cassocks and surplices also extended from the clergy to members of the Choir. The image above, from the unique color drawing of Queen Elizabeth I’s funeral procession, shows some of the Choristers from the Chapel Royal wearing their cassocks and surplices, a practice surely duplicated at St Paul’s Cathedral.

John Gipkin’s famous painting of 1616 (see image below) depicting a Paul’s Cross sermon in progress shows the preacher wearing a cassock, surplice, tippet, and Canterbury cap.

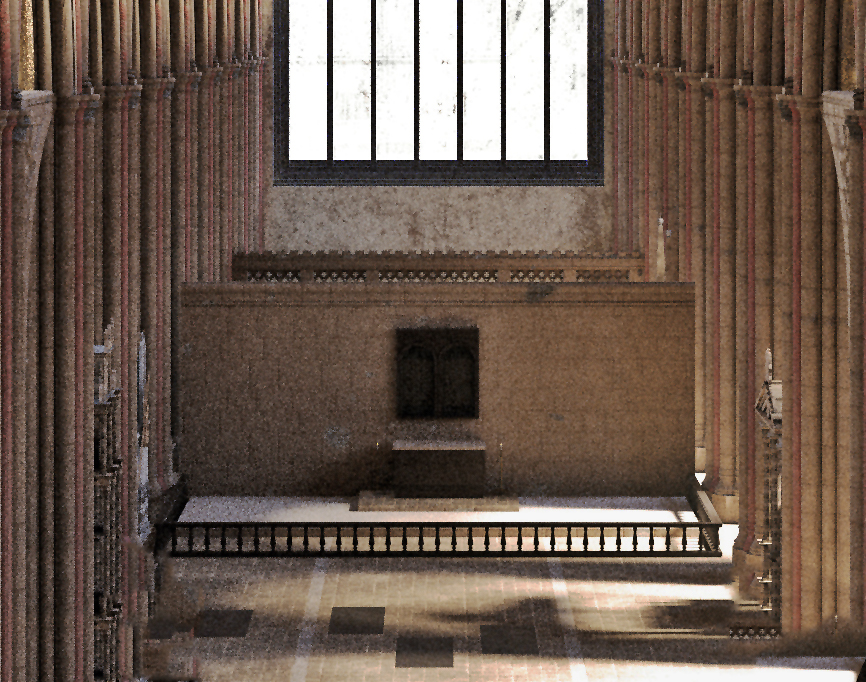

The Books of Common Prayer of 1559 and 1604 instruct clergy that “the minister at the time of the Communion, and at all other times in his ministration shall use such ornaments as were in use by authority of Parliament in the second year of the Reign of Edward the Sixth,” which would seem to mandate that the priest celebrating Holy Communion would wear the traditional vestments of an alb over his cassock (instead of the surplice) and a chasuble or a cope.

The image below, also from the color drawing of Queen Elizabeth I’s funeral procession, shows that use of the cope persisted post-Reformation at the Chapel Royal.

We know that wearing a cope as part of worship persisted at St Paul’s Cathedral as well. Accounts of Donne’s being formally welcomed by the Canons of St Paul’s include their wearing copes over their cassocks and surplices and vesting Donne in his cope before they processed into the Choir for the formal ceremony of installation. [9]See Bald, John Donne: A Life (Oxford University Press, 1970, pp. 381. See also, for the ritual of installation as Dean of the Cathedral, see William Sparrow Simpson, ed. Registrum Statutorum et … Continue reading

What did not persist, however, was widespread use of chasubles, at least until their use was recovered in the Church of England in the mid- to late 19th century. And, of course, the Puritan wing of the Church of England objected to all these vestments as popish rags.

We therefore conclude that Donne, as Dean of St Paul’s, wore a cassock, surplice, and tippet (and perhaps a Canterbury cap as well) when participating in the Daily Offices and other non-eucharistic worship services at the Cathedral. When celebrating Holy Communion, taking part in formal processions, and performing other ceremonial functions as Dean of the Cathedral, he would have worn a cope.

MUSIC

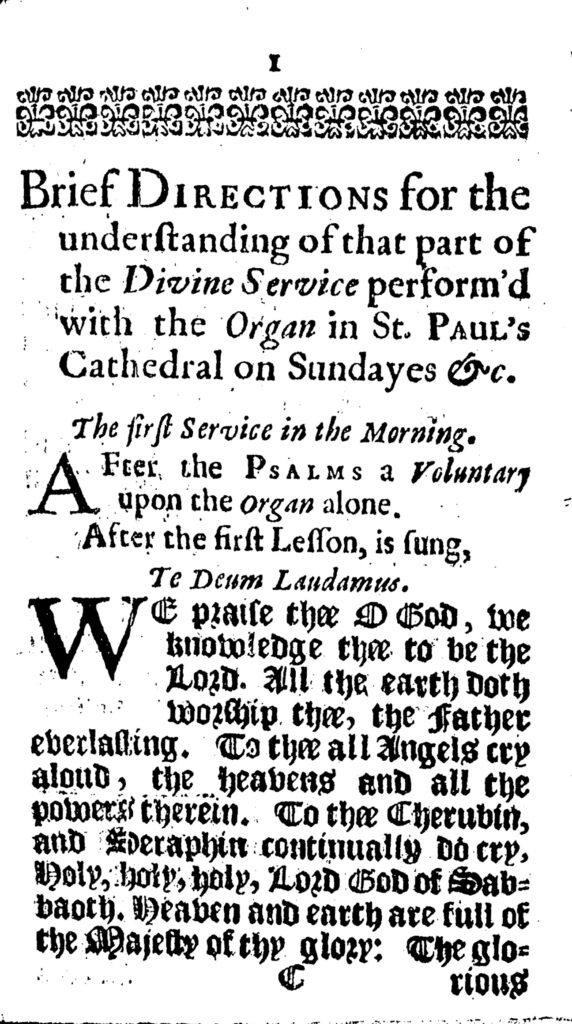

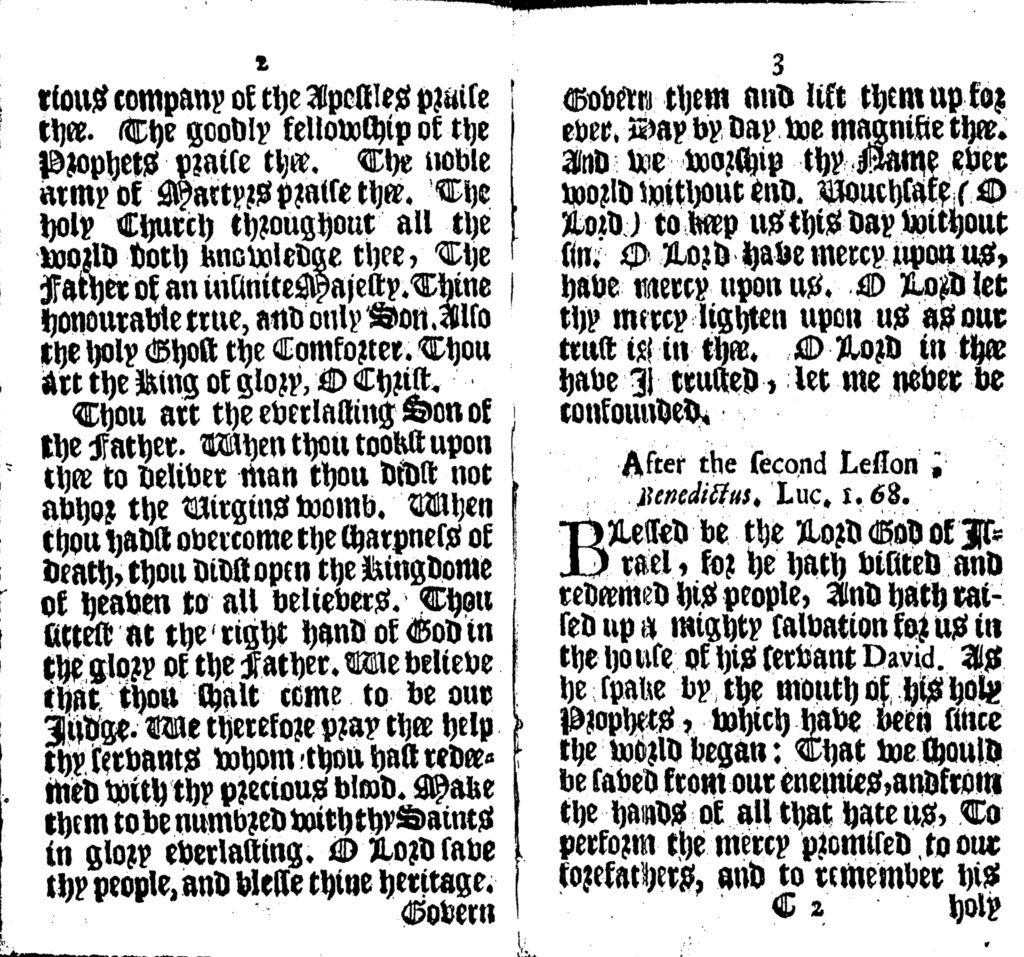

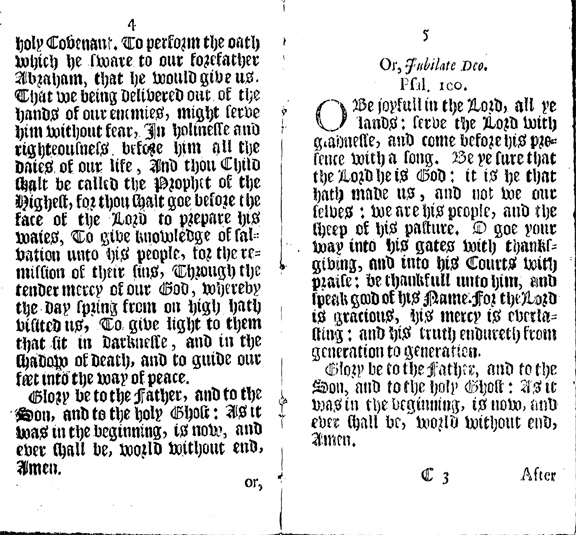

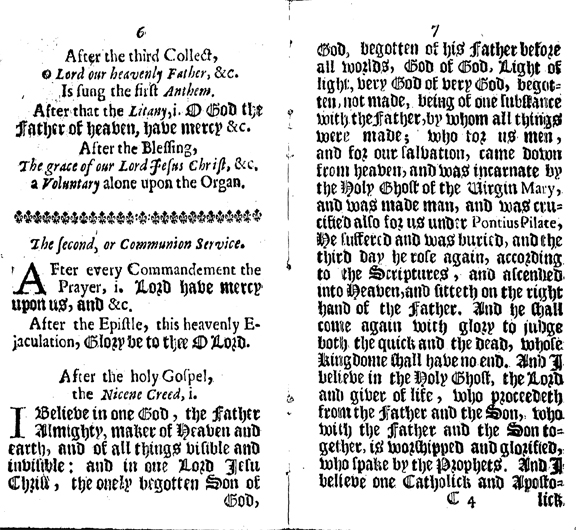

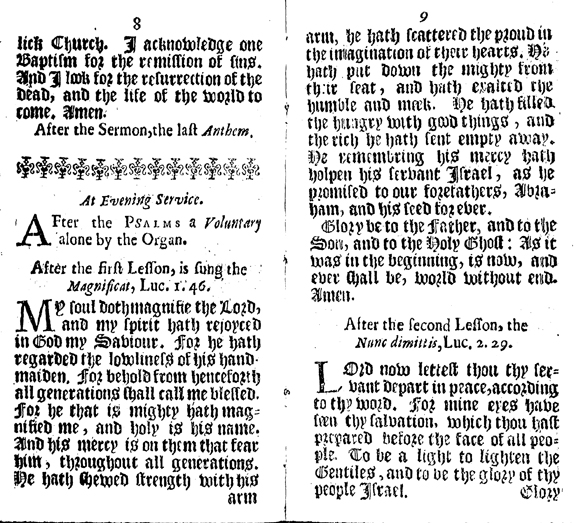

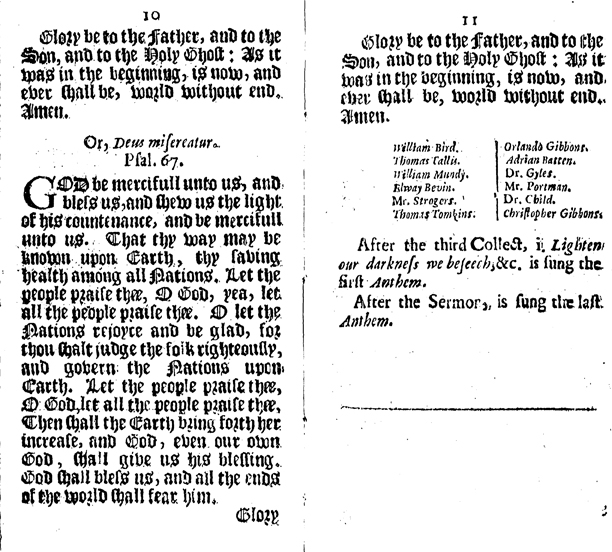

Our decisions about types and locations of organ and choral music have been guided by James Clifford’s, The divine services and anthems usually sung in His Majesties chappell and in all cathedrals and collegiate choires in England and Ireland (London, 1664). After the Restoration of the Church of England in 1660 and the reopening of St Paul’s as a functioning cathedral, Clifford set out to respond to the continuing complaints of the Puritans that they could not understand the words in the music sung in choral settings of Prayer Book worship. So, he decided to print the words of the Canticles and Anthems “usually sung in His Majesties chappell and in all cathedrals and collegiate choires in England and Ireland.” In the process, he includes a description of “that part of the Divine Service perform’d with the Organ in St Paul’s Cathedral on Sundayes,” a description we have followed for the location of organ voluntaries, anthems, and other parts of Divine Service.

Of course, Clifford is describing worship at St Paul’s post-Restoration, so it is possible that the way of doing things changed between 1643 and 1664, or, for that matter, between Donne’s death in 1631 and the closing of the Cathedral in 1643. But Clifford is describing a practice only two or three years after the recommencement of sung services at St Paul’s, as part of a Restoration, not a rebeginning, in a part of Church life that tends to be very conservative in regard to change in the best of times. In light of all that, and in the absence of any other, more timely, guides to the order of service, we have chosen Clifford as our ours.

[1] The Lambeth Articles, never officially adopted by the Church hierarchy, embody Calvinist beliefs about human depravity and human dependence for hope on the eternal will of a remote and abstract God. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lambeth_Articles for the full text.

[2] David Bagchi, “‘The Scripture moveth us in sundry places’: framing biblical emotions in the Book of Common Prayer and the Homilies,” in Richard Meek & Erin Sullivan (eds), The Renaissance of Emotion: Understanding Affect in Shakespeare and his Contemporaries (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), p. 54.

[3] All quotations in this essay from the Book of Common Prayer are, for the purposes of convenience, from the edition of 1559, ed. by John Booty (Folger Library, 1976). Donne at St Paul’s would have used the edition of 1604, essentially a reprint of the 1559 edition except for updating in various prayers and other texts to reflect changes brought by the accession to the throne of James I).

[4] A loose translation of the traditional Latin affirmation lex orandi, lex credende.

References

| ↑1 | See Martin Thornton, English Spirituality (1963 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a discussion of Richard Hooker’s “hypothetical universalism,” see Michael J. Lynch. “Richard Hooker and the Development of English Hypothetical Universalism,” in Richard Hooker and Reformed Orthodoxy, eds. W. Bradford Littlejohn and Scott N. Kindred-Barnes (Bristol, CT: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017), pp. 273-293. |

| ↑3 | Hence convinced that one’s status before God depended on God’s eternal decree regarding someone rather than on any temporal event in which that person might participate; for how the history of the post-Reformation Church of England looks from within this perspective, see Alec Ryrie, Being Protestant in Reformation Britain (Oxford, 2013) and “The Reformation in Anglicanism,” In The Oxford Handbook of Anglican Studies (Oxford, 2015), pp. 34 – 45. |

| ↑4 | For discussions of the Prayer Book’s role as a component of Thomas Cranmer’s broader Reform program of social transformation of England into the true Christian Commonwealth which Cranmer embodied in the Great Bible, the Book of Homilies, and other official books of the English Reformation, see the opening chapters of John N. Wall’s Transformations of the Word: Spenser, Herbert, Vaughan (1988), as well as his “Godly and Fruitful Lessons: The English Bible, Erasmus’ Paraphrases, and the Book of Homilies.” In The Godly Kingdom of Tudor England, (1981), pp. 45-135 and “The Book of Homilies of 1547 and the Continuity of English Humanism in the Sixteenth Century” Anglican Theological Review, 58 (1976), 75-87, as well as other sections of this website. |

| ↑5 | See Judith Maltby, Prayer Book and People in Elizabethan and early Stuart England (Cambridge, 1998) for an informed discussion of the limits on implementation of the English liturgical reformation and on lay response to dissenting clergy. |

| ↑6 | William Harrison, The Description of England (second edition 1587; rpt. Dover, 1968) p. 36. |

| ↑7 | In The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England, c. 1400 – c. 1580, second edition (Yale, 2005) p. 593 |

| ↑8 | In The Description of England (1587, rpt. ed Georges Edelen, Dover Publications (New York1968 |

| ↑9 | See Bald, John Donne: A Life (Oxford University Press, 1970, pp. 381. See also, for the ritual of installation as Dean of the Cathedral, see William Sparrow Simpson, ed. Registrum Statutorum et Consuetindinum Ecclesiae Cathedralis Sancti pauli Londinensis. (London, 1873). |