Panorama of London with old St. Paul’s Cathedral seen from the north. From the collection of the Berlin State Museum, image courtesy of ARTSTOR.

St Paules great Church challenging the superioritie of all other land buildings for its antiquitie, greatnesse, loftinesse and majestie . . . appearing to sight amonge the rest of the Churches and common buildings as a stately Elephant with an Ambarree or Indian pavilion on his backe doth in the midle of an Armie of horse and foote.

— Peter Mundy, 16361

This section of the website is devoted to St Paul’s Cathedral and its surrounding Churchyard as physical objects with histories of construction and function and the Cathedral as an institution within the structure of the Church of England. We explore the history of the Cathedral building and its Churchyard, and locate them in the story of the English Reformation. We also describe the place a cathedral had in the organizational structure of the Church of England and the Diocese of London. The continued existence of cathedrals in the post-Reformation Church of England has puzzled many historians. For example, Christopher Haigh, who has argued that the Reformation “should have killed off cathedrals in England”; their survival, to Claire Cross, is “surprising”; to Diarmaid MacCulloch, their survival is “one of the great puzzles of the English Reformation.”2 But their presence as physical embodiments of episcopal governance and their function as symbols of the diocese at prayer seems entirely understandable for a Church resolved to be, or out of necessity came to be, a Church pragmatic in its determination to accommodate a nation of diverse spiritualities. 3

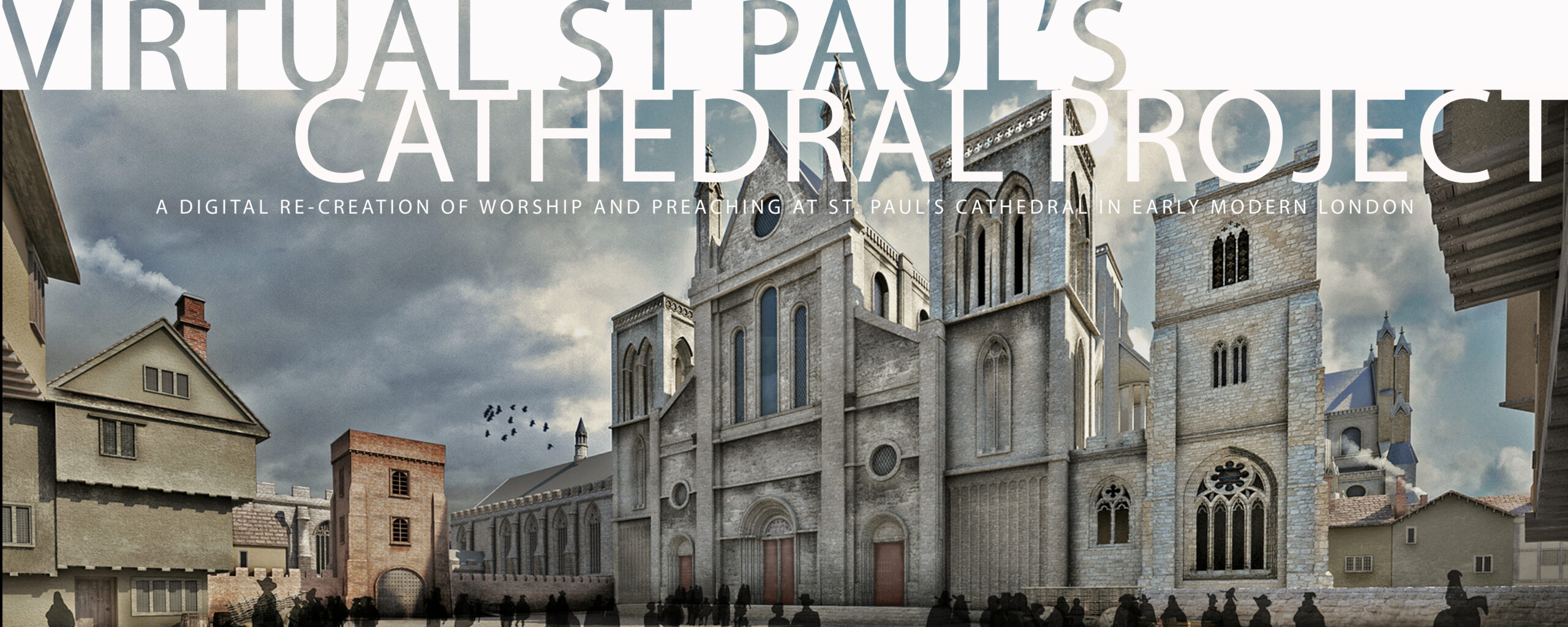

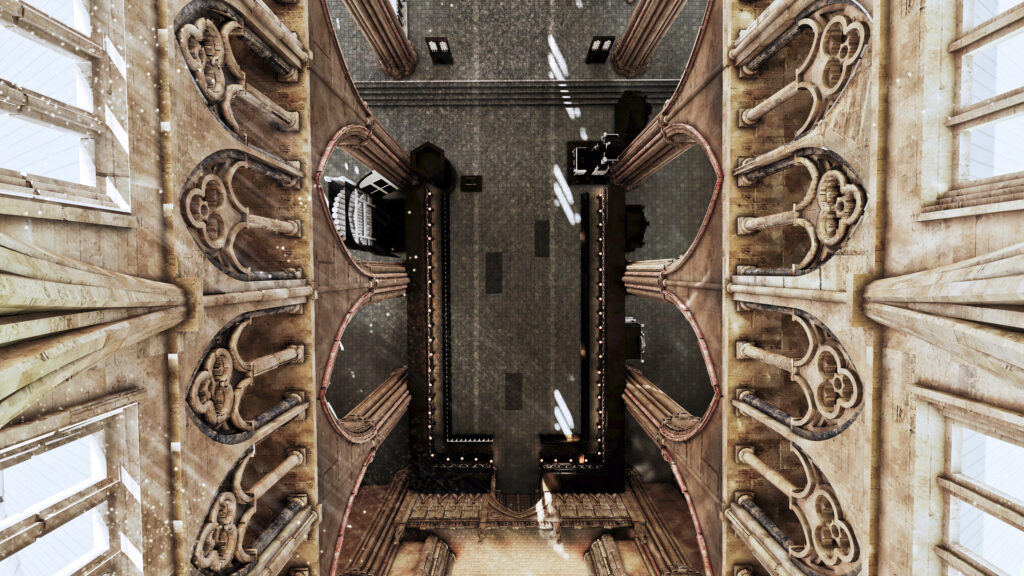

Our point of reference is the decade between 1621 to 1631, when John Donne was Dean of the Cathedral, a period roughly 60 years after the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) gave enduring form and substance to the post-Reformation Church of England. Throughout this period, and in spite of ongoing concerns that the structure of St Paul’s was in serious disrepair, St Paul’s continued to be the dominant physical structure in the entire city of London, as all the contemporary images of early London testify.

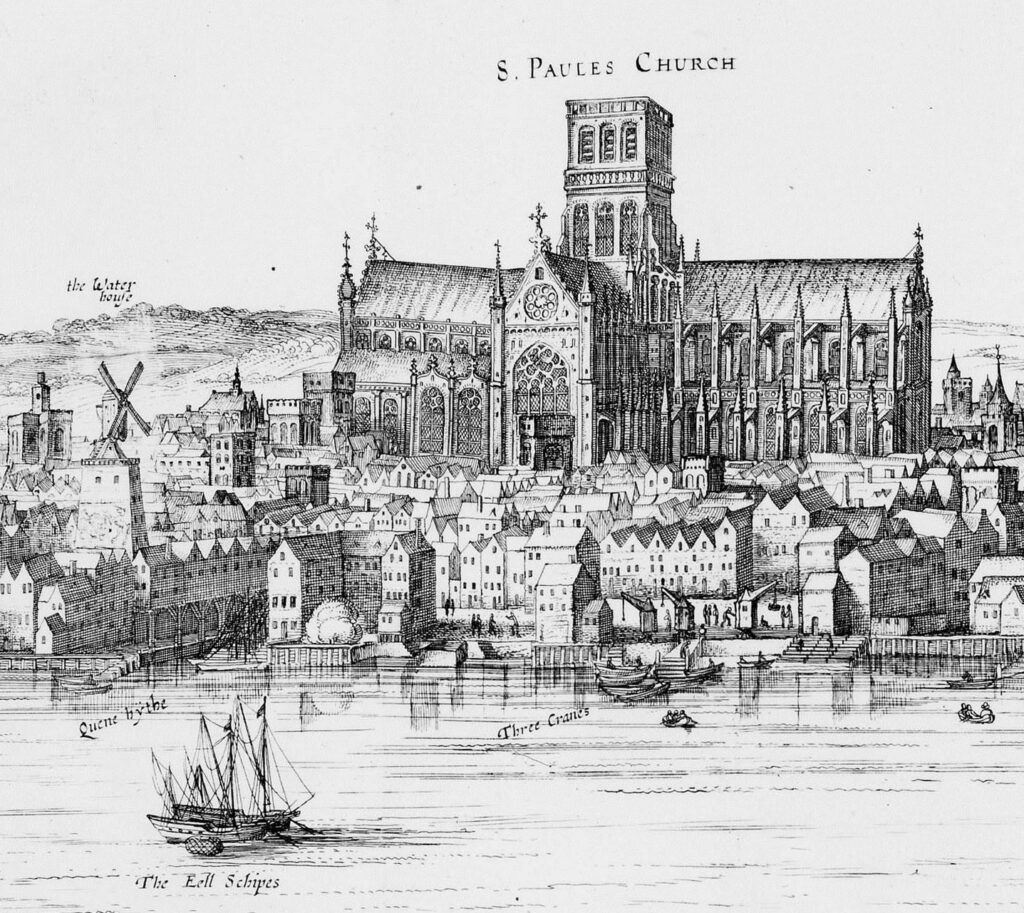

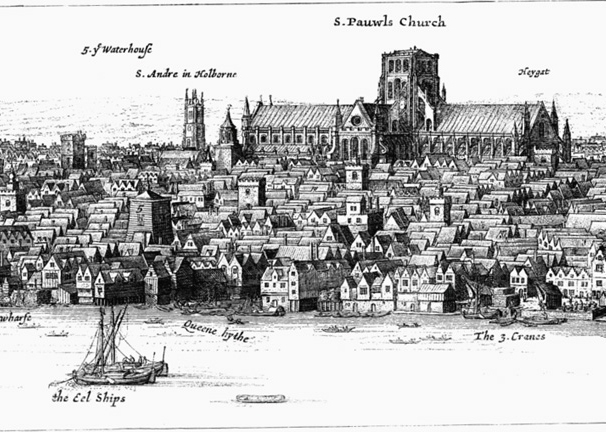

In Visscher’s View of London (1616), St Paul’s Cathedral rises up dramatically above the top of Ludgate Hill to tower above the City of London, spread out around it. Since Visscher never actually saw London, his sense of the relationship of scale between the Cathedral and its City may exaggerate the relative size of the Cathedral (compare his View with that of Wenceslaus Hollar, who had seen it), but it captures the importance of the Cathedral for the life of the City of London in the seventeenth century.

Both Visscher’s and Hollar’s panoramic views of the City of London make clear St Paul’s Cathedral was a significant physical presence in the City, its location near Ludgate marking the western boundary of the City, even as the Tower of London marked its eastern boundary. As such, it served as a point of spatial orientation from which directions could be given or the progress of journeys marked. This role was enhanced by the sound of its bells that rung the hours or called people to worship, audible more widely than the bells of parish churches because of the height of the bells and their lack of impediment from other buildings.

The Cathedral also served as the center of administration for the Diocese of London, with the residence of the Bishop of London and the site of his administrative offices standing at the northwest side of Paul’s Churchyard. Adjacent to the Bishop’s Palace was the Bishop’s official Chapel, where Donne was ordained by John King, Bishop of London, on January 23rd, 1615.

The organizational structure of the Church of England in the seventeenth century was strongly hierarchical, as it had been in the Middle Ages, strongly organic in self-understanding, and strongly geographical. When Englishfolk thought of the Church of England they thought of a church that was coterminous with the nation itself. Baptism in one’s local parish church was mandatory; one’s baptismal record was thus both a record of incorporation into the Church of England and of citizenship in the nation of England. This sense of the union of populace, worship, organization, and geography was reinforced by the Reformation’s transfer of ultimate responsibility for the Church from the Pope to the Monarch of England.

Each organizational unit of the Church of England also represented a geographic area of the country. The entity called the Church of England was divided into two parts, or Provinces, the Province of Canterbury and the Province of York. Each Province was administered by an Archbishop. The Archbishop of York was the Primate of England, while the Archbishop of Canterbury was the Primate of All England, as a sign of his being senior in authority to the Archbishop of York.

Each Province was subdivided into Dioceses, each one of which had its own Bishop. Each Bishop had his own cathedral, a church that served as the Bishop’s church and housed his cathedra, or throne, a basic symbol of his office. The act of seating a new Bishop in his cathedra, inside his cathedral, was a major moment in the rite of consecration for a new Bishop. The cathedral itself served as an embodiment of the unity of the Diocese, where the daily round of worship was conducted and prayer for the nation, the Diocese, and the individual parishioner was offered.

Each Diocese was divided into Archdeaconries, each one of which was administered by an Archdeacon. The archdeacons together comprised the senior administrative staff of the Bishop of the Diocese.

Each Archdeaconry was subdivided into parishes, each of which had a parish church. Each parish church was administered by its own rector or vicar. A small exception to this structure were the collegiate churches, of which only a few survived the Reformation. Chief among them was Westminster Abbey. Collegiate churches were distinctive in that they were not subject to the authority of the Bishop of the diocese in which they were located but instead were responsible directly to the Crown.

In this hierarchic structure, authority flowed downward. The Crown chose archbishops from among the current members of the episcopate. Bishops, collectively, consecrated new bishops. Bishops named archdeacons from among the current set of priests. Bishops ordained priests and deacons. Priests (and of course Bishops as well) baptized, celebrated Holy Communion, preached sermons, and maintained the Daily Offices and their round of prayer and readings from Scripture. Priests and Deacons ministered to the physical and spiritual needs of their congregations.

The organizational structures of the Church of England, as worshipping communities, nested within its larger structures of administration and authority, created a nation at worship and at prayer, in unity of voice and purpose. The post-Reformation Church of England was, therefore, from the beginning, corporate, liturgical, and sacramental, providing support and guidance in the maturing of one’s faith and assurance that its members were “very members incorporate in the mystical body of [Christ], which is the blessed company of all faithful people.” Or, as Harrison puts it, “the whole congregation at one instant [could] pour out their petitions unto the living God for the whole estate of His church in most earnest and fervent manner,” enabled to do so of course by the rites of the Book of Common Prayer, at services of worship led by ordained clergy in their parish churches.

In the Church of England’s hierarchy, the City of London was at the heart of the Diocese of London, a diocese within the Province of Canterbury. During John Donne’s tenure as Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, George Abbot was Archbishop of Canterbury, serving from 1611 until 1633. George Montaigne was Bishop of London from 1621 – 1627; he was then succeeded by William Laud. The Archdeacon of London when Donne became Dean of the Cathedral was Theophilus Aylmer, who had been appointed in 1591 and continued as Archdeacon until his death in 1626. Aylmer was then replaced by Thomas Parke, who served until the abolition of the Church of England after the Commonwealth victory in the English Civil War. 4

While the early years of the English Reformation had seen conflict over the kind of Reformation the English Reformation would be, by 1621 the new had become a habitual part of daily life. People had become familiar with the language and structure of reformed public worship and had developed a sense of the kind of religious tradition the Church of England was coming to be.

The story of St Paul’s Cathedral in the late 16th century and early 17th centuries mirrors this narrative. The Cathedral’s responses to the Injunctions of 1598 suggest an organization that is unsure about its purpose and therefore careless in the way it went about the work of the Cathedral. We hear of Choristers who wear dirty vestments and come late to the services, seemingly more interested in collecting spur money from the men of fashion who flocked to display themselves in the Cathedral’s Nave than in singing Divine Service. The organ seems not to be in the best of repair. And so forth.

At the same time, however, there were signs of new life, especially as represented by the work of composers who were called upon to supply music for cathedral choirs and the choirs of collegiate churches like Westminster Abbey and the Chapels Royal at Whitehall and Windsor Castle. The challenge of producing new music for English texts and Prayer Book services was first taken up by the generation of Tallis, Marbecke, and others, to be succeeded by the generations of Byrd, Gibbons, and others — so that by the early decades of the seventeenth century, the flourishing of the English Choral Tradition had begun. Eventually, the preservation of this music fell especially to the Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral, where John Barnard, who became a Minor Canon at St Paul’s in 1623, and Adrian Batten, hired by Donne as a Vicar Choral in 1626, brought together manuscripts of this music into large collections now housed in the Archives of the Royal Academy of Music in London and the Bodlean Library at Oxford University.

Interestingly, John Barnard’s collection of manuscripts at the Royal Academy — one of the sources for his First Book of Selected Church Musick (1641) — gives us a glimpse of life among the choristers at St Paul’s Cathedral. One of the scores of musical settings for the Canticles of Morning and Evening Prayer comes in two versions — one for use when the full Choir was on hand, and one for use when the boys were on vacation in the summers. Such information — together with the Cathedral’s responses to the Laudian Visitation in the mid-1620’s — help give us the sense that organizationally things had been put right, for the work of the Cathedral seems to have been done decently and in good order for some time. The English priest and poet George Herbert — who used to slip away from his post as rector of St Andrew’s Church, Bemerton, to attend choral services at nearby Salisbury Cathedral — might have been describing St Paul’s as well when, in his poem “The Brittish Church,” he celebrated the Church of England as neither too high nor too low, neither too Catholic nor too Protestant, but just right.

The British Church

I joy, dear mother, when I view

Thy perfect lineaments, and hue

Both sweet and bright.

Beauty in thee takes up her place,

And dates her letters from thy face,

When she doth write.

A fine aspect in fit array,

Neither too mean nor yet too gay,

Shows who is best.

Outlandish looks may not compare,

For all they either painted are,

Or else undress’d.

She on the hills which wantonly

Allureth all, in hope to be

By her preferr’d,

Hath kiss’d so long her painted shrines,

That ev’n her face by kissing shines,

For her reward.

She in the valley is so shy

Of dressing, that her hair doth lie

About her ears;

While she avoids her neighbour’s pride,

She wholly goes on th’ other side,

And nothing wears.

But, dearest mother, what those miss,

The mean, thy praise and glory is

And long may be.

Blessed be God, whose love it was

To double-moat thee with his grace,

And none but thee.5

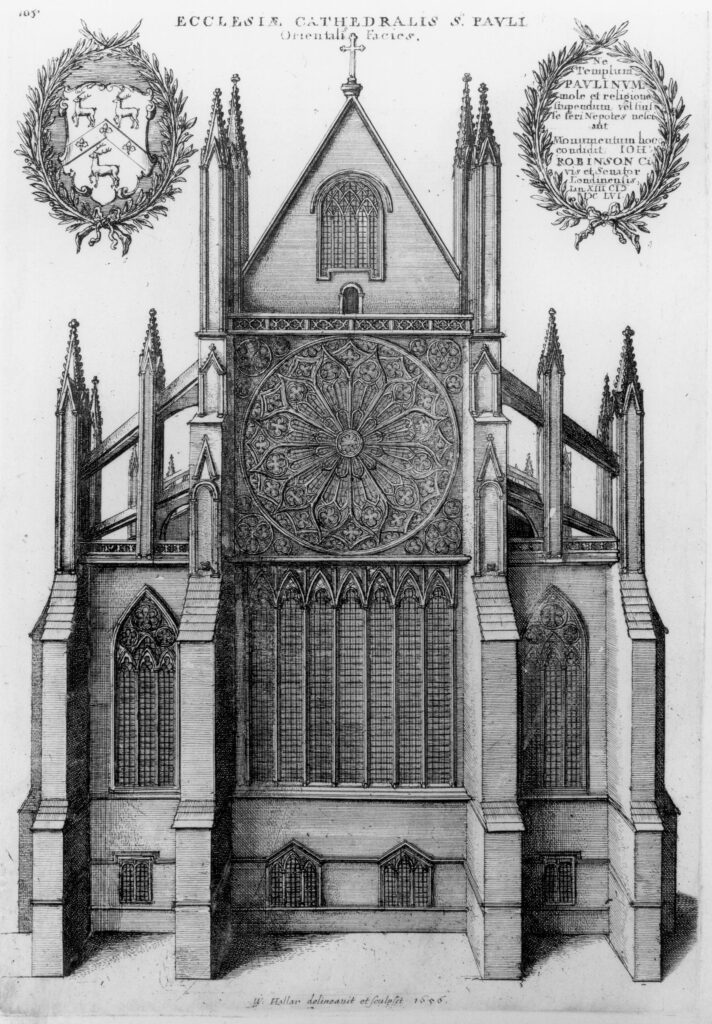

St Paul’s Cathedral, the East Front. Engraving by Wenseslaus Hollar.

Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

REFERENCES

- Who, having been to India, knew an elephant when he saw one.

- See Christopher Haigh, Why Do We Have Cathedrals? A Historian’s View, St. George’s Cathedral Lecture, no. 4 (Perth, 1998), pp. 2 – 6, also Claire Cross, “‘Dens of Loitering Lubbers’: Protestant Protest against Cathedral Foundations, 1540– 1640,” in Schism, Heresy and Religious Protest, ed. Derek Baker, vol. 9 of Studies in Church History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972), p. 237; MacCulloch, Later Reformation in England (MacMillan, 1990), p. 79.

- On cathedrals, post-Reformation, see Ian Athereton, “An Apology of the Church of England’s Cathedrals,” in Defending the Faith : John Jewel and the Elizabethan Church, edited by Angela Ranson, André A. Gazal, and Sarah Bastow (Penn State, 2019), pp. 98-118.

- Look under the tab COMMUNITY for a fuller account of the Cathedral’s staff during Donne’s tenure as Dean.

- George Herbert, “The British Church,” from George Herbert: The Country Parson, The Temple, ed. John N. Wall (Paulist Press, 1981), pp. 229-30.