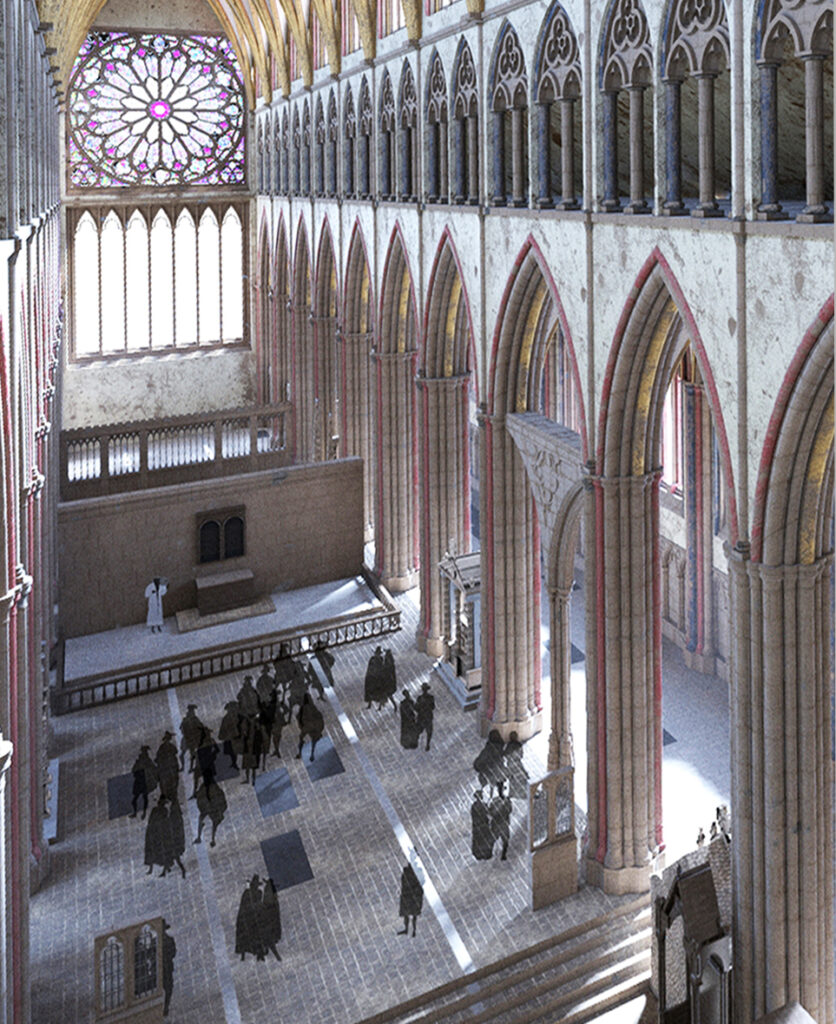

This section of the Cathedral website offers a walking tour of St Paul’s interior, with the goal of identifying parts of the interior and their functions and clarifying the relationships among the various structures and locations within the Cathedral itself.

Please note: Details of images of the Cathedral’s interior in the images and panoramic views below may reflect different stages in the evolution of our Visual Model, so details such as the colors of the vaulting, the placement of floor tiles, and the shape of doorways may vary from image to image.

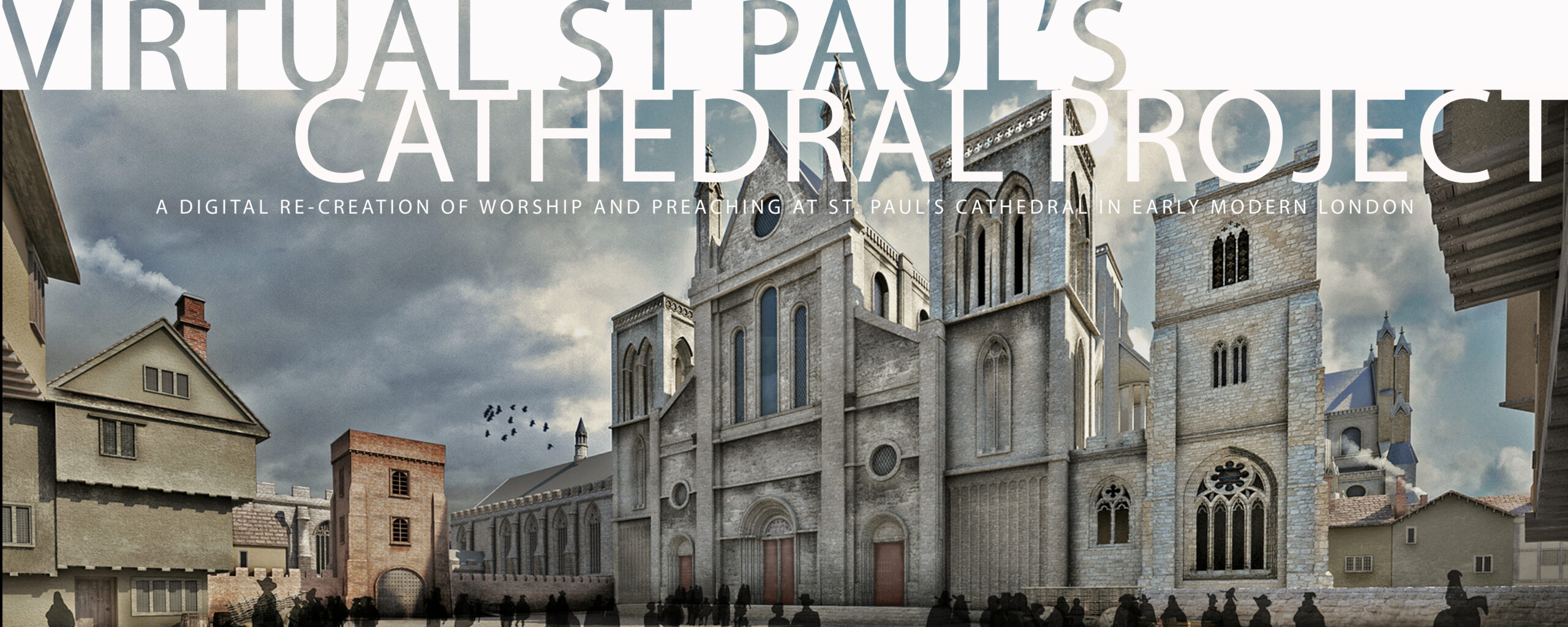

We begin our tour as we approach the Cathedral’s West Front, headed toward the doors in the center of the façade.

We then enter the building, moving into the center of the Nave. Looking eastward, we see in the distance the Choir Screen, with the ceiling of the Choir opening above it and the Great Rose Window glowing in the morning sunlight, in view in the distant East Front.

Looking westward, back toward the Great West Front, we see the windows and the door through which we entered this space. The structure on the right is the tomb of Thomas Kempe, Bishop of London, who died in 1489.

In the Middle Ages, this space was used for liturgical processions and for celebrations of Mass by chantry clergy. Given the fact that it was the largest enclosed space in the city of London, however, it also became a place where people gathered out of the weather for commercial and legal transactions.

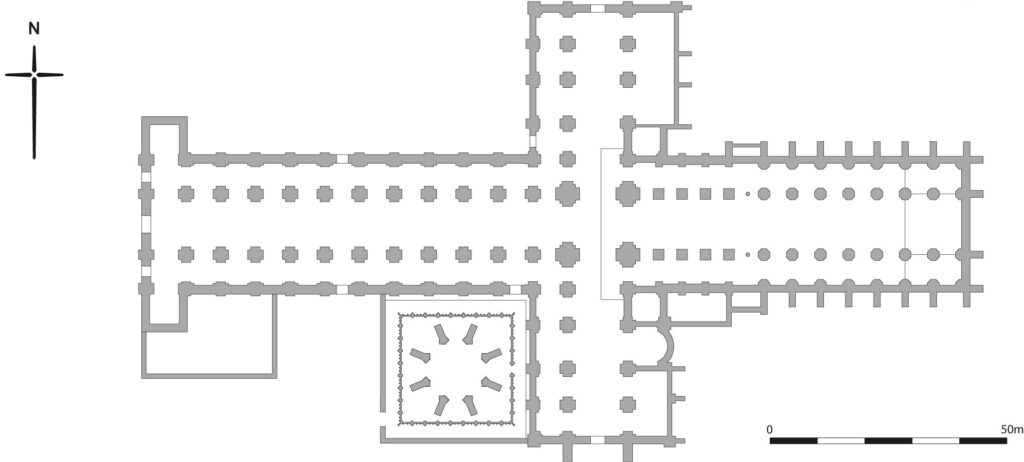

These activities were encouraged by the fact that the Cathedral blocked access from the south to the north, channeling movement of personal and commercial life through the transepts or through the passageway across the Nave created by the doorways on either side of the Nave, about halfway between the West Front and the Crossing, as alternatives to taking the long way around the ends of the building.

Post-Reformation, this space became dedicated almost exclusively to secular and commercial activities, earning for itself the name Paul’s Walk because it was a place where people of fashion came to see and be seen. [Footnote Roze Henschell, St Paul’s Cathedral Precinct in Early modern Literature and Culture (Oxford UP 2020, pp. 23-67).

Continuing our journey eastward once more, we come to the Crossing, where the North and South Transepts intersect with the Nave. Before us are the steps leading up to the Choir and Choir Screen, which separates the Nave from the Choir.

Overhead in the Crossing is the underside of the (now truncated) Tower, above which are the Cathedral’s bells. We show the Crossing Tower in both the cool light of morning and the warm light of evening.

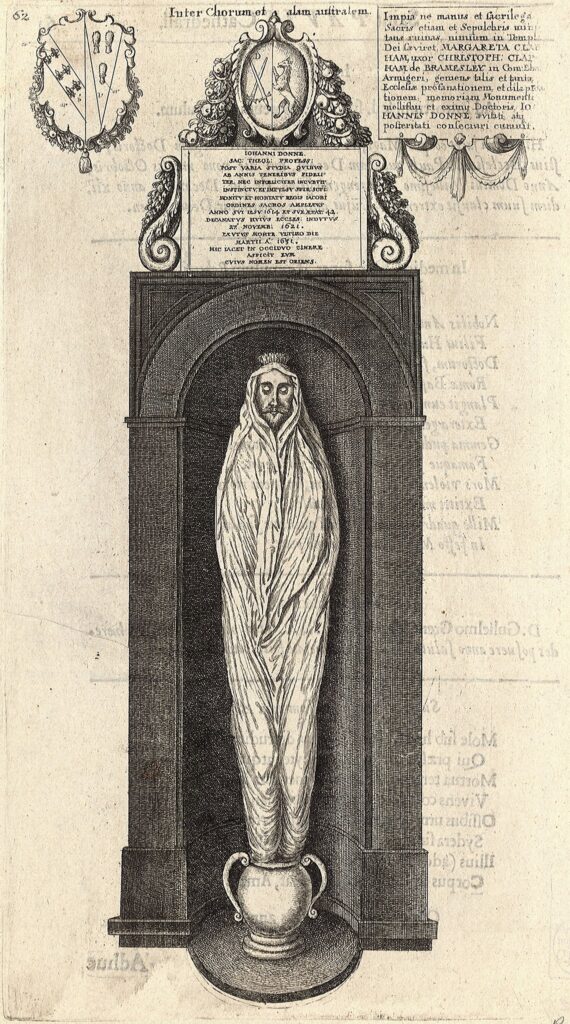

Above the ceiling of the Tower are the Cathedral’s bells, used for ringing out calls to prayer and announcements of deaths among members of the Cathedral community. These bells therefore anchored a form of communication network for people living within the sound of the Cathedral’s bells. One is reminded of John Donne’s comments about the ringing of these bells in his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions.

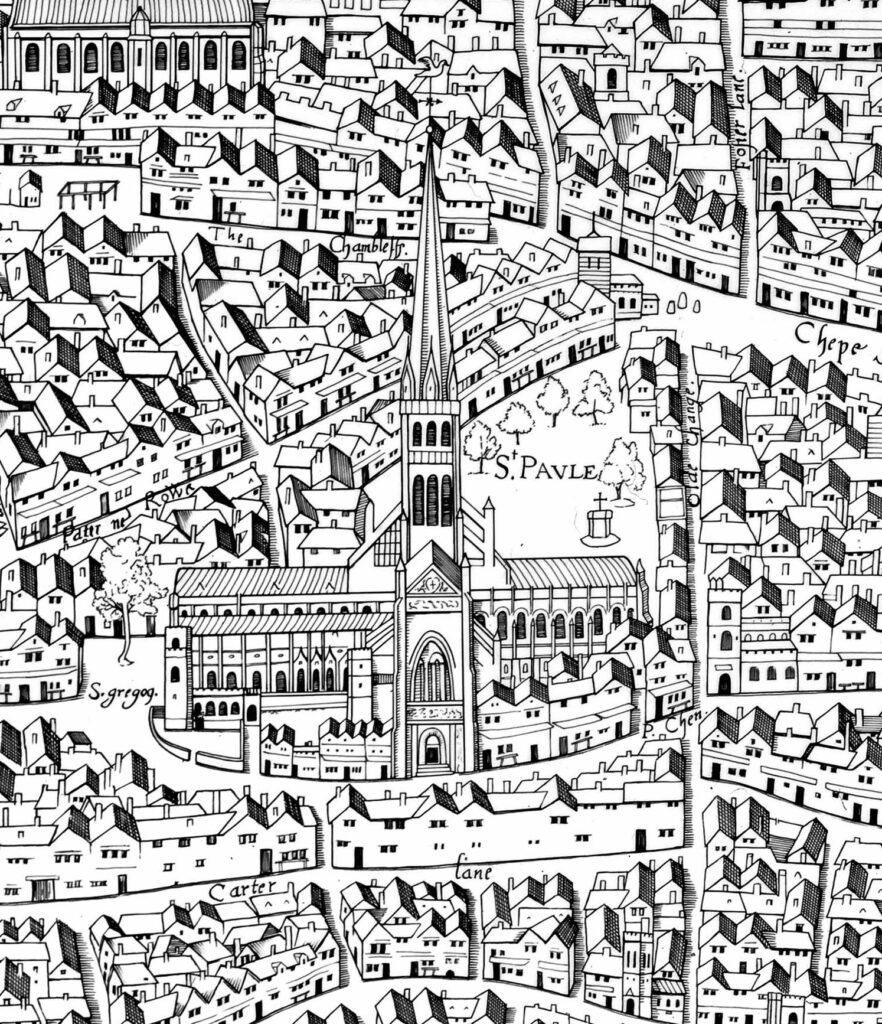

The Cathedral’s tower burned after being struck with lightning in 1561 and was never rebuilt. The image to the right, from the Copperplate Map of London, shows the Cathedral’s spire in all its pre-1561 glory.

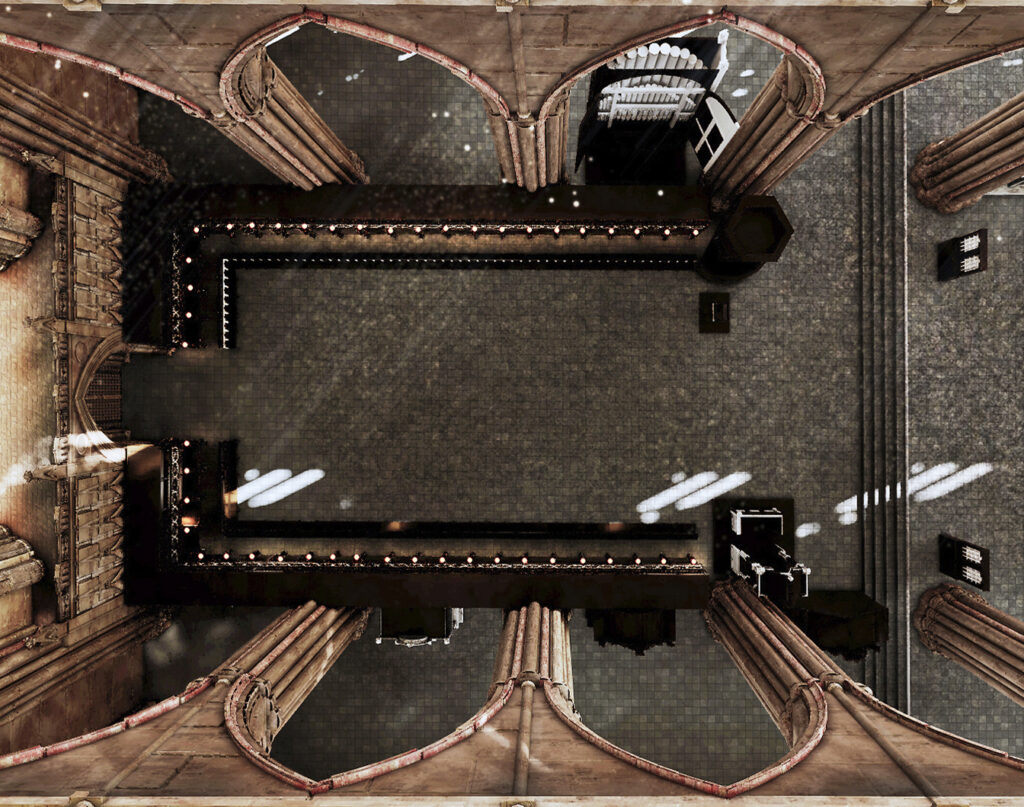

As we look up into the Tower, this is a good time to notice the entire ceiling of the Cathedral, stretched out from end to end.

We now move up the steps and through the Choir Screen into the Choir itself. The Choir area stretches before us, beginning with the Choir Stalls where daily in the morning and afternoon the Cathedrals’ Choir and the resident clergy assembled for Morning and Evening Prayer, to read the appointed Lessons from the Old and New Testaments, chant the appointed Psalms, and offer prayers for divine assistance on behalf of all members of the Diocese of London.

The image to the right shows the Choir area as seen from the stall assigned to the Dean of the Cathedral, John Donne from 1621 to 1631. To the left, above the Choir Stalls, is the Cathedral’s organ. Below the organ is the Choir’s pulpit, from which Donne and other preachers at the Cathedral delivered their sermons. On the floor is the lectern, holding a copy of the Authorized, or King James, Bible from which the Lessons from the Bible for the day and the occasion were read.

To explore a 360 degree panoramic view of the Choir as seen from the east end of the Choir stalls, click on this block of text.

At the end of the right bank of stalls is the Cathedral’s cathedra, or Bishop’s Throne, the official seat of the Bishop of the Diocese of London and one of the basic symbols of his episcopal office. It is also the word, and the function, that give the building itself the name of cathedral and identifies this building as the official church of the diocesan bishop.

This image shows the Choir from the pulpit. Each of the 30 Canons or Prebends of the Cathedral Chapter had his own stall in the Choir. Our model shows a bench running the length of the stalls, for members of the Choir to sit.

We have followed Hollar’s image of the Choir in not showing any additional furniture in this area of the Cathedral. But it seems likely that there was an additional long prie-dieu, or prayer desk, running along in front of the Choir bench to hold music and to provide kneelers for the members of the Choir.

We chose to model all the windows as glazed with white glass, having been advised that medieval stained glass was probably destroyed during the waves of iconoclasm that took place in the years following the Reformation.

We have been reliably informed that a new program of stained glass, depicting scenes in the life of the Apostle Paul, was installed in the Choir in the early seventeenth century. Having no idea how extensive it was, or what specific scenes it depicted, we considered several possible ways to indicate the presence of such a program, such as to color light coming through these windows when it hit the floor or the furniture. But, we ultimately decided not to try such an experiment in depiction.

We have now moved up the flight of steps into the area between the Choir Stalls and the Altar and are looking back at the Stalls. From here, the Bishop’s Throne is more prominently visible. We turn around to face east and see the space between the Stall area and the Altar area.

Now we have faced eastward and moved up to balcony level for a look at the Altar area. The Altar is shown here, following Hollar, against a wall that separates the Choir area proper from the east end of the building. It is also shown railed in.

This is approximately the spot where the High Altar was located in medieval St Paul’s. Behind it was the shrine of St Erkinwald, a site of pilgrimage and devotion pre-Reformation. We imagine that, in the decades immediately following the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion in 1559, the Altar was located away from this wall, somewhere in the area between the steps and the wall shown here, turned to be oriented north/south on its longest side.

We know the altar was — by the reign of Charles I — located in the position shown in this image because there was a dispute between the clergy at St Gregory’s parish church and the Cathedral clergy over the location of the Altar. At St Gregory’s, the Altar stood away from the wall, while the Altar stood, as shown here, against the wall. The dispute was ultimately taken to Charles for adjudication; Charles ruled in favor of the position the Altar occupied inside the Cathedral.

In our model, we have taken the position that, by the time Donne became Dean of the Cathedral, the transition in the Altar’s location in the Cathedral’s Choir had already taken place.

In the image to the right, we have moved to the balcony and are looking down on the east end of the Choir. The priest at the altar has consecrated the bread and wine of communion and is welcoming members of the congregation — perhaps the Lord Mayor of London and his entourage — who are coming to the Altar to receive the consecrated elements while kneeling at the Altar rail.

In this image, we have moved from the Altar area and into the South Aisle of the Choir. To our left is the monument for John Colet, Dean of the Cathedral in the early 16th century.

In our image of the South Aisle, members of the congregation for a service going on in the Choir have not found seating in the Choir itself but have decided to stand while listening to the service. One imagines that Donne’s sermons — and perhaps the sermons of other preachers on Sunday afternoons — would have drawn a crowd that exceeded the seating capacity of the Choir stalls. Who actually attended worship services at the Cathedral is unclear, although we are promised by the folks preparing the new Oxford edition of Donne’s sermons that they will address this issue in the preface to one of their volumes of Donne’s Cathedral sermons.

The problem is that — as the church of the entire Diocese of London — the Cathedral itself had no formal congregation. As is discussed elsewhere on this website, people who lived in Paul’s Churchyard but were not employees of the Cathedral or responsible for worship services in the Cathedral were required to attend worship in one of the two parish churches located inside Paul’s Churchyard.

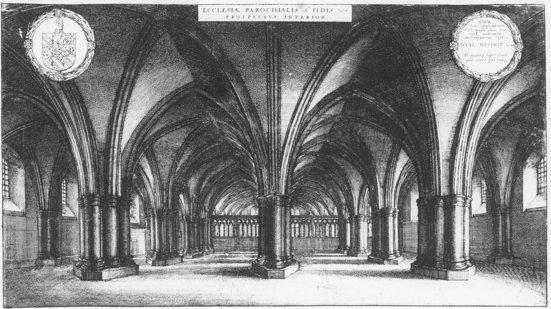

Folks who lived on the east and north sides of the Churchyard were required to attend services at St Faith’s church, which was located in the basement of St Paul’s, under the Choir of the Cathedral (see Hollar’s image of St Faith’s, below).

Folks who lived on the west and south sides of Paul’s Churchyard were required to attend services at St Gregory’s Church, found adjacent to the south side of St Paul’s West Front. So, in addition to those who had reason of responsibility for worship at St Paul’s, who attended? We know that the Lord Mayor of London and his entourage attended worship in St Paul’s on certain specific civic occasions during the year. Perhaps also visitors to London would have included worship at St Paul’s as part of their travels. Beyond that, we must await further archival research into worship habits for enlightenment.

In 1631, after Dean Donne’s death, his own monument was to be installed in the space between us and Dean Colet’s monument.

We now have moved east in the South Aisle of the Choir and reached the interior of the east end of the Cathedral. Behind us in the Medieval Cathedral would have been the Shrine of St Erkinwald; in front of us would have been St Mary’s Chapel. To the right of Our Lady’s Chapel would have been the Chapel of St Dunstan, while to the left would have been St George’s Chapel.

Finally, we have arrived in the North Aisle, shown in this image from our Virtual Reality model of St Paul’s, located here to provide a contrast to our other styles of rendering images of our models. We are here among more monuments to the Cathedral’s distinguished dead.

But we are ready to proceed west along the North Aisle, passing the Chapel built in memory of John of Gaunt, in Shakespeare’s words, “time honored Lancaster.” It was build to be a chantry chapel where Masses would have been said for the repose of the Duke’s soul; by the time of Donne’s Deanship, however, it had become a storage room for vestments and the space where members of the clergy taking part in worship in the adjacent Choir would have prepared for their task.

We could proceed back to the Crossing, and then down the Nave to the West Front to resume our day in London. If it were a regular Sunday when we visited, however, we could follow the clergy taking part in the day’s Paul’s Cross sermon by following the Verger down a flight of steps to a door at ground level and proceeding out into the Cross Yard in time for the sermon to begin.

Before leaving the Cathedral’s interior, we pause to look up for one last look at the expanse of the Cathedral’s Ceiling as it stretches out above us.