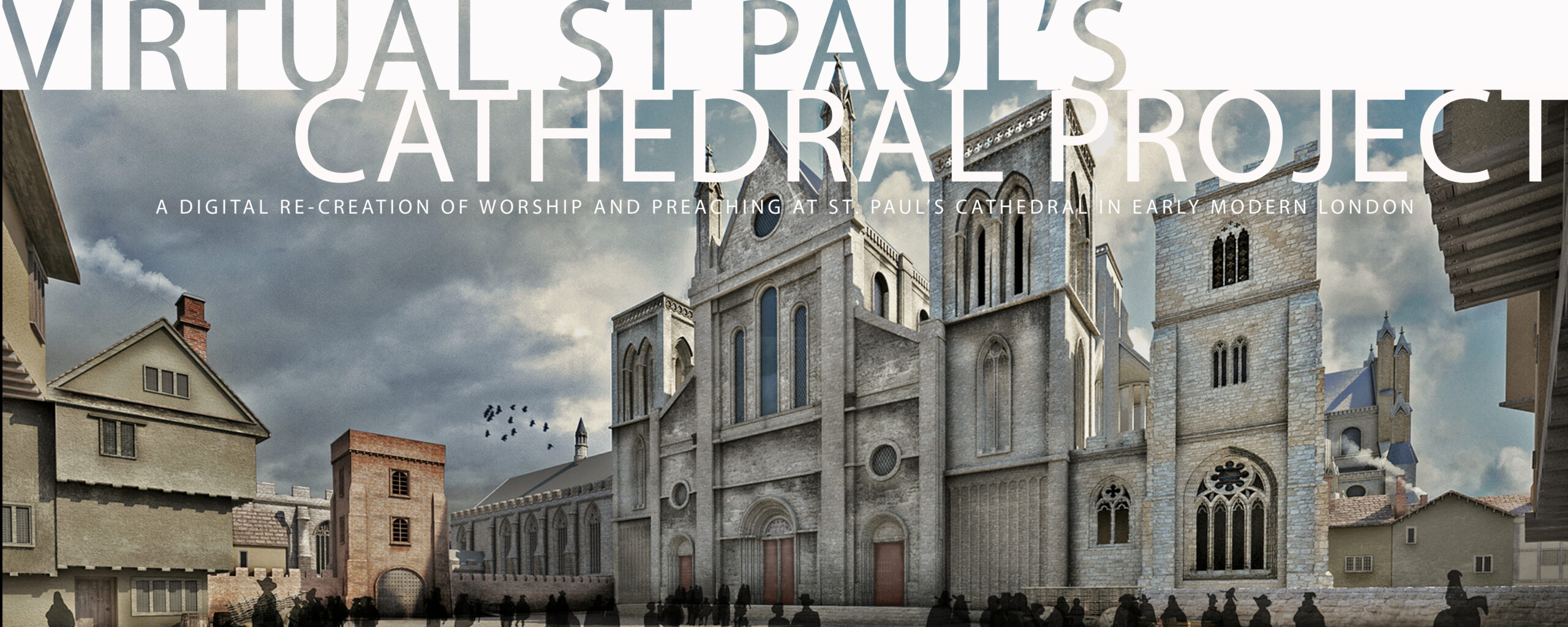

The digital tools employed by the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project enable us to integrate the physical traces of preFire St Paul’s Cathedral with the surviving textual and visual records of the cathedral and its surroundings to create a visual model of the Cathedral and its churchyard. They also enable us to experience a historically faithful interpretation of worship services and peaching performed in the Cathedral.

In accord with methodological principles for developing computer-based visualizations (and now auralizations) of historically significant cultural sites set forth in the London Charter for the Computer-based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage, the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project is defined as an “evidence-based restoration” of the Cathedral and its surrounding structures and spaces between 1621 and 1631, the years of John Donne’s tenure as Dean of the Cathedral.

Following the Charter’s concern for the importance of intellectual transparency in computer-based modeling and visualization of historic sites, the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project lists all research sources and seeks to clarify how the various kinds of historic materials came together to make possible what one sees and hears on this site. This includes discussions of sources for all the elements of what one sees and hears on this site, as well as assessment of the relative values of different kinds of evidence.

In addition, clear distinctions are made between those aspects of the site that 1. represent historic information, or 2. offer representative approximations of lost structures, or 3. recreate lost experiences. In the case of the latter of these aspects of the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project, the grounds for belief in the (extent of the) accuracy of approximations or recreations, as well as careful presentation of the assumptions guiding their development and realization are extensively delineated.

This approach is intended to help us to understand and evaluate our assumptions about the look and sound of cathedral worship in the early modern period, to add experience in real time to our repertory of tools for interpreting these events, and – because it is flexible and open to change – to create the opportunity for testing and evaluating multiple models of the event it recreates as new information and new interpretations emerge.

We also provide the opportunity to think through the idea that the lived religion of early modern England is essentially performative, a collaboration between clergy and laity, scripted by the Book of Common Prayer.