Work remains to be done in a number of facets of Donne’s career as a priest of the Church of England. Here are four examples:

1. Donne’s relationship with the church of St John the Baptist, Keyston

In 1616, the year after John Donne was ordained to the priesthood in the Church of England, he was appointed to the livings of two parish churches, the Church of St John the Baptist in Keyston, Huntingdon, and the Church of St Nicholas in Sevenoaks, Kent. Donne’s appointment at Keyston was made by King James I, dated 16 January 1616; presumably James was here following up on his promise to Donne to advance Donne’s career if Donne took Holy Orders.

RC Bald, in his biography of Donne (John Donne: A Life (Oxford 1970) details, on pp. 386 – 388, some complexities of this appointment, including the fact that the appointment had also been given to a priest named John Scott. Donne ultimately got the post at Keyston, but promised he would support Scott’s candidacy when the time came for Donne to resign the position.

When Donne resigned from his post at Keyston in October of 1621, just prior to his becoming Dean of St Paul’s later that November, he helped Scott obtain the post, which had also been promised to a priest named Henry Seylard.

In the midst of all this, we find that Donne felt he had not been appropriately paid his salary by the good folks at St Nicholas, so he brought suit to obtain his due.

This document is described in the Catalogue of the Archive as Personal responses to articles of libel against Thomas Hills of Sharnbrook, Bedfordshire, in a cause of substraction of tithes due to John Donne DD, Rector of Keyston, who had been Parson in 1620. Responses given in court before Thomas Morrison.

Image courtesy Huntingdonshire, England Public Record Office.

It reads as follows:

The answers of Thomas Hills of Sharnebrooke in the county of Bedfordshire in the diocese of Lincoln…assignor John Dunne, Master in sacred theology… recently Rector of Keyston, Huntingdonshire, in the diocese of Lincoln…

[To the first article the respondent believes that] one of the yeares…vizt [that is to say] the yeare 1620 the assignor John Donne doctor in Divinitie was commonly accompted and reputed to be parson of Keyston…

[To the second article, as in the first and second, he believes that it is true…]

[And to the fourth and fifth articles…] the respondent believes that the sayd yeare 1620 he this respondent held and occupied wthin the parish of Keyston aforesayd nine hundred and twelve acres of meadowe and pasture ground and noe more (vt credit ffiftie acres of the sayd meadowe and pasture vizt that wch he thisrespondent did mowe and conuert to haye being worth the sayd yeare every acre one wth another xxs legalis &c (vt credit) and noe more And the other eight hundred threescore and twoo acres of the sayd meadowe and pasture vizt that wch he did feede and eate downe wth cattell being worth the sayd yeare every acre one wth another vjs legalis &c (vt credit) and noe more. The tythe of wch sayd fiftie acres mowed and conuerted to hay as aforesayd he this respondent did duely pay vnto the ffarmor or deputie of the sayd Mr Doctor Dunne. And for the tythe of the sayd eight hundred threescore and twoo acres fed and eaten downe wth cattell as aforesayd this respondent doth believe that he ought not to pay or be troubled for any tythe thereof in regard that the Lady Wingfeild and Sir James Wingfeild her sonne did demise and let all the sayd nyne hundred and twelve acres vnto the respondent tythe free and did vndertake to satisfie the sayd Mr Doctor Dunne for the tythe of the sayd eight hundred threescore and twoo acres

[To the sixth statement, the respondent believes that it is true.]

[To the seventh statement, the respondent doesn’t believe that it is true.]

[To the eighth statement, the respondent believes that it is true.]

[To the ninth statement, the respondent believe that in the former case, it is true, and denies what is denied; and as for the other, he doesn’t believe that it is true.]

Repeated 8 August 1625 in our court Signed Thomas Hills

Thomas Morison

The following account — “Parishes: Keyston,” in A History of the County of Huntingdon: Volume 3, ed. William Page, Granville Proby and S Inskip Ladds (London, 1936), pp. 69-75. <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/hunts/vol3/pp69-75> — points toward approaches to filling out the background and alerts us to the fact that this court case deals with matters of land valuation and revaluation and the history of land enclosures.

Of St Nicholas , we are told that

The church at Keyston was valued in 1291 at £18 13s. 4d. and in 1535 at £30 1s. 6d. In 1428 it was assessed at twenty-three marks, and paid 37s. 4d. to the subsidy. The advowson was attached to the manor and followed the same descent. It was acquired before 1764 by Charles, Marquess of Rockingham; it descended to Mr. G. C. Wentworth-Fitzwilliam, whose executors are now patrons. The tithes in Keyston seem to have been of considerable value, for about 1620, when Sir James Wingfield proposed the inclosure of over 1,700 acres of land, the rector, John Donne [the History says it was Scott, but Scott did not become the vicar of Keyston until after Donne resigned in 1621], ‘perceiving the great inconvenience which was to arise to the church,’ resisted the proposal and refused to receive tithes in kind out of the inclosure, declaring that the rectory was thereby disinherited almost to the value of one-half yearly. Upon this complaint, ‘to prevent the disherison of the said church and to make the said parsonage of as good, or neere as good, value as it was before,’ Sir James and his tenants agreed that arbitrators ‘of qualitie and conscience’ should be chosen by common consent ‘for establishing such a yearly rate upon the new inclosed grounds as they in their consciences and discretions should think to be equall ratably and respectively for the proportion of the said lands.’ Sir Robert Payne and Sir Lewis Pemberton, the chosen arbitrators, decided that the inclosure should pay 1s. 8d. an acre yearly to the rector and his successors in lieu of tithes. Notwithstanding their agreement, Edward Bate and Thomas Hilles, ‘two substantiall tenants’ and owners respectively of 120 and 850 acres of the inclosure, neglected to pay their share. The rector brought an action against them in chancery; whereupon Edward Bate declared that the rate was exorbitant, and begged ‘not to be compelled to pay as sett down by the referees’; while Thomas Hilles pleaded that, having consulted Edward Maria Wingfield and learned that ‘Dame Mary,’ probably the widow of Sir Edward Wingfield, ‘was not willing to encumber the inheritance with this perpetual rent charge,’ he did not absolutely agree to it, but ‘did pay at times to stay suits until there might be some friendly agreement.’ “

2. The baptism at Sevenoaks

Of all the sermons that Donne preached at Baptisms (Christenings), four survive. None indicate, however, the identity of the child being baptized. Erica Longfellow, editor of the forthcoming volume of Donne’s sermon at marriages, christenings, and churchings, volume VII in the edition published by the Oxford University Press, once suggested, in a paper delivered at the Conference of the John Donne Society in 2011, that at least one of these sermons was preached at the Baptism of the child of a nobleman.

The parish records of St Nicholas, Sevenoaks, Kent supply one possible candidate. According to the parish registry, Lady Mary Sackville, born on the 4th of July 1625, was baptized at St Nicholas on July 15th of that year. Her father was Sir Edward Sackville, 4th Earl of Dorset; her mother was Mary Curzon Sackville, Countess of Dorset. The Sackvilles lived at Knowle, the great country house 3 miles from St Nicholas.

When the Lady Mary Sackville was baptized in 1625, Donne had been the pluralist rector of St Nicholas, Sevenoaks, Kent, since since 1616. Sackville, who had recently inherited the title of Earl of Dorsett, was a person who, according to Bald (p. 455), arranged in 1624 for Donne to become vicar of St Dunstan’s in the West.

Bald says Donne in the summer of 1625 was staying with the Danvers in Chelsea; one could easily imagine his making the 20 or so mile journey to visit his parishioners in Sevenoaks, spend some days with the Sackvilles at Knowle, baptize the Lady Mary, and preach on the occasion. After all, there were 11 days between her birth and the baptism for all to be arranged, and, clearly, Donne owed the Earl a big favor.

One might consult the Household Account Books of the Sackville family at Knole, which might have guest lists for meals, also accounts of household expenses, which might turn up a record of Donne’s being in residence for this event.

3. The furniture at Blunham

During a pilgrimage to the parish churches where Donne served as (absentee) rector, I was told by the rector of St Edmund’s Church in Blunham that she had been told that several pieces of the liturgical furniture in the building were survivals from the Middle Ages, including the pulpit and a side altar, which, she said, had originally been the main altar. Given the look of the pulpit, her comments might have merit as more than local legend.

It would be especially interesting to determine if the side (previously main) altar at St Edmund’s were the one in use when Donne made his occasional visits to the church and celebrated Holy Communion there.

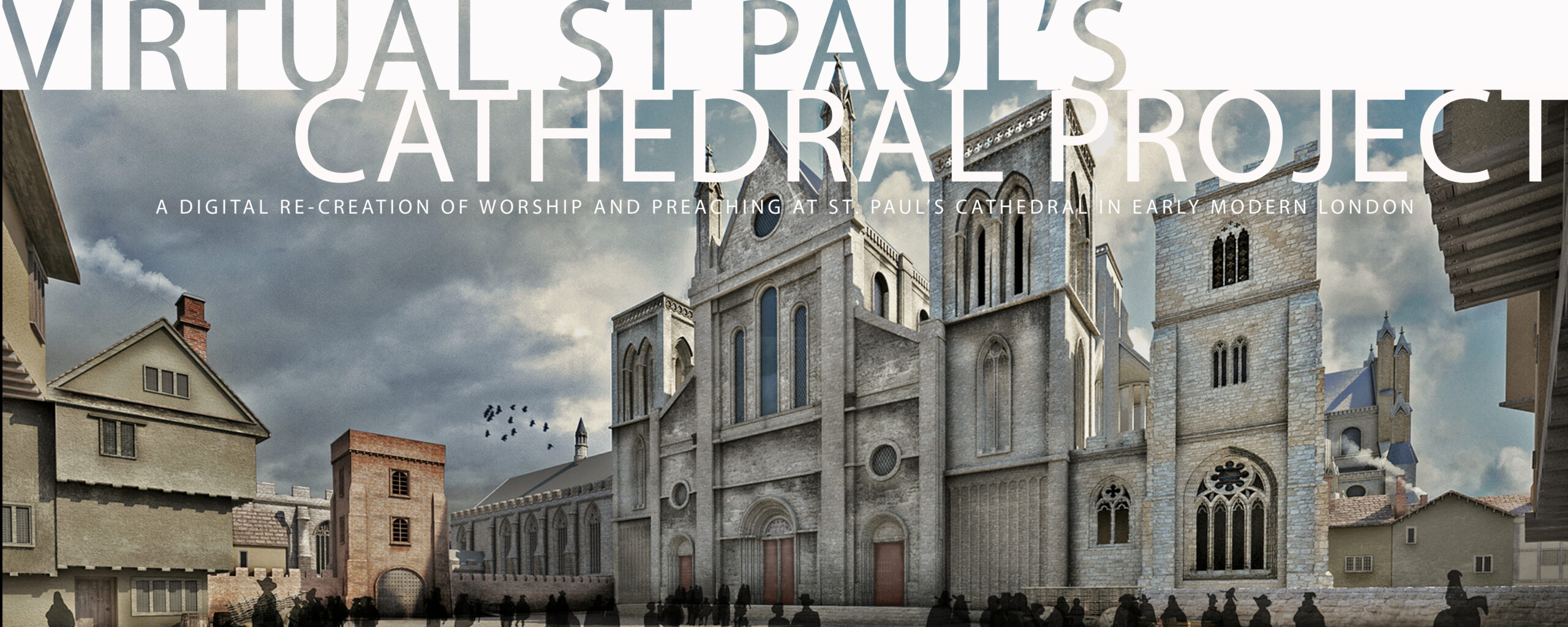

4. The (Lack of) Repair of the Fabric of St Paul’s Cathedral

In contemporary accounts, St Paul’s Cathedral in the early seventeenth century is always falling down, or, at least, in need of serious repairs. Details of the kinds of repairs the Cathedral needed are rarely given, but one might imagine leaky roofs, decaying stonework, and the perennial question of replacing the spire, destroyed by fire after a lightning strike in 1561.

In 1616, a new effort to fund repairs got under way, a project which produced the famous painting of St Paul’s by John Gipkin. Funds were raised, materials were purchased, and delivered to Paul’s Churchyard.

Then Donne became Dean of the Cathedral, and nothing further was done. The materials purchased for the repairs sat in the Churchyard throughout Donne’s tenure. There are stories that the Duke of Buckingham eventually (was given permission to remove, took the liberty of stealing) some of this material for repairs on his London home. Donne’s inaction is one of the great mysteries of Donne’s tenure as Dean, awaiting the discovery of a letter or other source to clarify

Only after Donne’s death did work begin anew on repairs, except at this point Inigo Jones, the King’s Architect, was called in and given permission to redesign an entirely new neo-classical façade for the building, at least some of which had been completed by the time William Dugdale hired Wenceslas Hollar to make the engravings of Jones’ work.

5. Donne and the Brentwood School

In 1622, shortly after becoming Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, John Donne, along with Bishop of London George Montaigne, and Sir Anthony Browne of Brentwood, in Essex, signed and sealed a legal document that represents the Charter for the Brentwood School, founded in 1558 by Anthony Browne’s ancestor Anthony Browne during the reign of Mary Tudor.

John Donne, Seal. Photograph courtesy John N Wall.

John Donne, Seal. Image by Wenseslas Hollar. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Two areas for further research arise from this document. One is the seal itself, the same seal that appears on the monument to Donne erected in St Paul’s, near the moneuent to John Colet, Donne’s predecessor as Dean of the Cathedral. The seal shows, on the left, the crossed swords that are part of the crest of St Paul’s Cathedral. To the right, it shows a rearing wolf, an element in the family crest of the Donne family.

So this seal is the official seal Donne used as Dean of the Cathedral to certify official documents he signed as Dean of the Cathedral. Donne must have signed many documents during his ten years as Dean, but this impression, on the Charter of the Brentwood School, may be the nly one that survived the Great Fire.

The second point at which further research is warranted is the fact that the Charter Donne, Montaigne, and Browne signed in 1622 finally gave legal standing to a school that had been functioning without a Charter since 1558. It is unusual for the Brentwood School to have functioned for so many years without clear legal standing.

One possibility for the delay is that the Browne family had been a Catholic family for many generations. Donne, of course, grew up in a recusant family. Is there a chance that Donne’s willingness to get involved in getting the Browne family’s long-missing charter represents another chapter in Donne’s relationship with the English Catholic community, now that he was Dean of St Paul’s?