An Odd Work of Grace

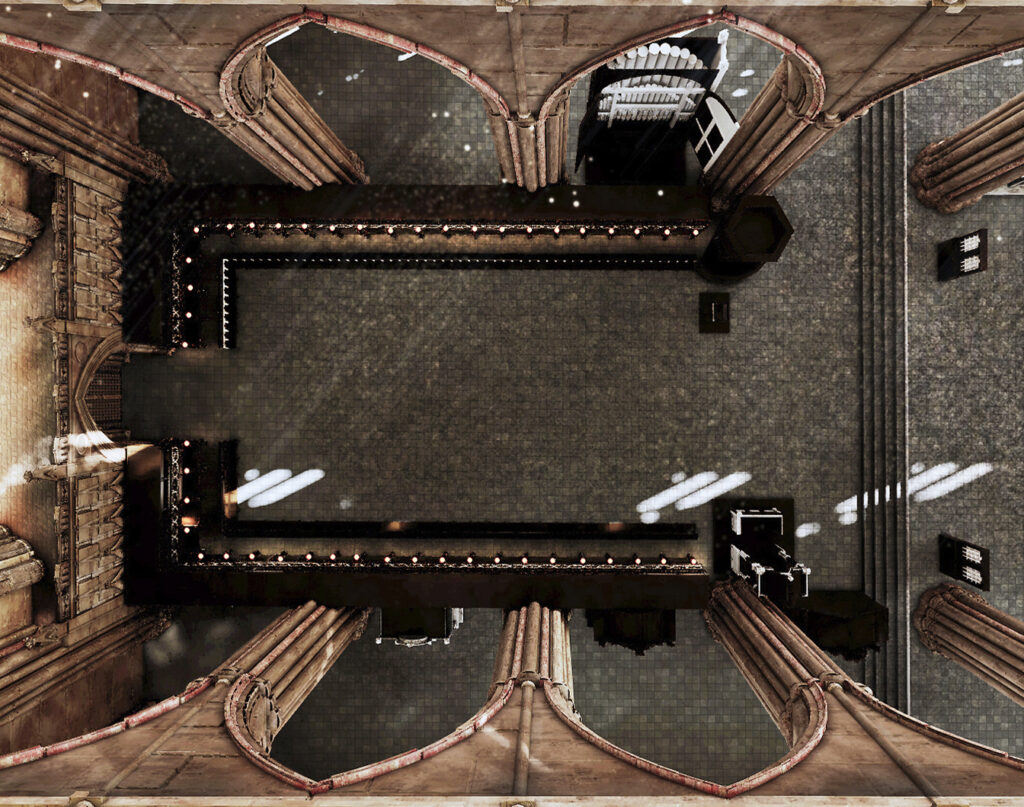

The purpose of the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project is to make the liturgies authorized by the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) available to us as experiences that unfold in real time in one of the spaces in which they were fully implemented. The early modern Church of England, given birth in the liturgical reforms initiated under Edward VI in the 1550’s, given essentially final form in the Elizabethan Settlement of 1559, and given reaffirmation under James I in 1604, incorporated basic concerns of the European Reformation while giving them its own particular formulation and practice; at the same time it preserved and continued far more of the customs and practices of the medieval Church than other reformed churches, an aspect of the English Reformation that is often ignored.1 The distinctive character of the English Reformation is of course embodied in the lived religion of England as it put into practice the corporate round of worship enabled by the Book of Common Prayer and its supporting documents.

Cranmer’s distinctive efforts at reform in fact move in two directions at once — his reformation through use of the Book of Common Prayer broadened the scope of monastic religious life by using the services of the monastic hours as models for daily worship in cathedrals and parish churches (see the attached Table of Continuities for a fuller list) while it simultaneously reshaped the meaning of the Eucharist, recovering and putting in practice patristic understandings of Eucharistic presence as meaningful in the corporate action of priest and congregation as it recited the narrative and received the elements of Jesus’ Last Supper with his Disciples. This degree of continuity, together with the distinctiveness of change and the goal of social reform — building up the true Christian Commonwealth — are what set the English Reformation apart from other European Reformations.

Continuity and Change

The Church of England’s defining combination of continuity and change is realized most fully in the experience of the lived religion its basic documents create. So our goal with the Virtual Cathedral Project is to make this “odd work of Grace”2 accessible in practice — materializing the ephemeral — in its distinctive form and substance. We must grant — given the absence of extensive data confirming liturgical practices on a parish-by-parish basis — that the extent of parish compliance with the Prayer Book’s rites and rubrics during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I is difficult to establish. On the one hand, the legal requirements for the Prayer Book’s possession by every church and cathedral, its required use to enable people to meet at least the minimum number of times to receive communion each year, and the bishops’ use of Visitations to assess compliance with these legal requirements all remind us that congregations were under scrutiny about their compliance and suggest that they felt pressure to comply.3 Therefore, one suspects that the vast majority of English churches did use the Book of Common Prayer, and used it to a greater or lesser degree of compliance with its rubrics. The matter of objecting to use of the Prayer Book at all — a centerpiece of Puritan demands — is yet another sign that the Prayer Book was used widely.

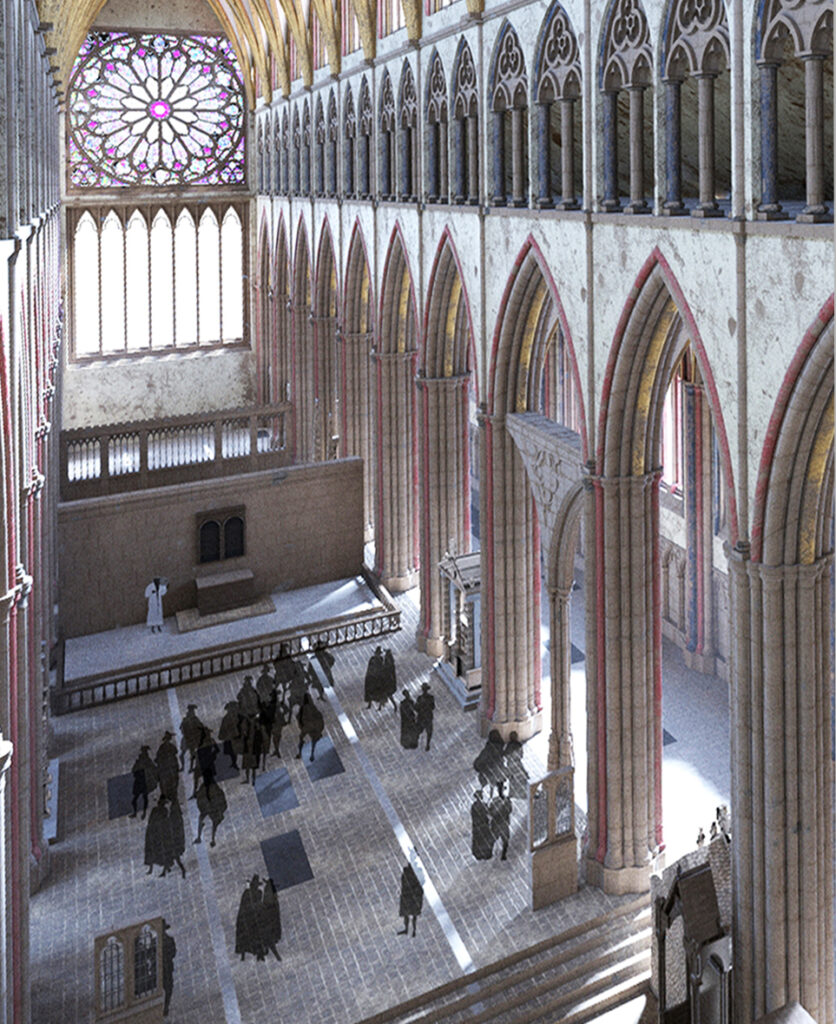

Whether or not this is in fact the case, we can be reasonably confident that if Cranmer’s goals for the liturgical life of English cathedrals and parish churches were realized anywhere, it was St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Hence our attention to worship at St Paul’s as a way of making the Church of England available for study as it was in practice, in performance. Basing our work on a recreation of a cathedral that no longer exists rather than in one of England’s many surviving medieval cathedrals enables us to focus on the interior arrangements of the building as it was in the immediate post-Reformation period rather than having to work around the rearrangements of worship space that have taken place inside existing English cathedrals in the intervening 350 years.4

Corporate, Pragmatic, Liturgical, and Sacramental

Recognizing that the organizing of public worship was at the heart of religious reform in 16th century England enables us to understand more fully how the religious life of early modern England was far more a faith to be practiced than it was a body of doctrine to be affirmed. This is, of course, reflected in the fact that the official documents of the English Reformation were about changing the style, language, and structure of public worship rather than about articulating a dramatically different understanding of the Christian faith. While movements for religious reform across Europe resulted in massive theological tomes, the Reformation in England produced a collection of books — the Great Bible, the Book of Common Prayer, the two Books of Homilies, the Ordinals, and the Primers — all of which were about enabling the practice of public worship.5

As far as the faith of the Church of England was concerned, the community was enabled to proclaim it through the recitation of the historic creeds of the Patristic Age. In John Jewel’s view, the Church of England of the Elizabethan Settlement was not so much a refounding of the Church as it was a recovery, or resumption, of the beliefs and practices of the Patristic age.6 In this view, the Church of England is really the true Church, not Roman Catholicism, which had gone astray. Or, as Lancelot Andrewes put it, the Church of England is understood through its affirmation that

One canon reduced to writing by God himself, two testaments, three creeds, four general councils, five centuries and the series of fathers in that period – the three centuries, that is, before Constantine, and two after, determine the boundary of our faith.7

The Prayer Book provided scripts for worship services that, from Baptism to Confirmation to Holy Communion to Marriage to Ministry to the Sick and Dying to the Burial Office, staged, supported by grace, and informed a lifetime of participation in the corporate life of the Church, a corporate religious life that was pragmatic, liturgical and sacramental. The Prayer Book lectionaries brought the Bible into the recital of the Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer chapter by chapter, moving through (most of) the Hebrew Bible once a year, (most of) the New Testament three times a year,8 and the Book of Psalms twelve times a year. The Books of Homilies provided sermons for clergy who were unable to gain licenses to preach from their diocesan bishops to deliver during the rite of Holy Communion on Sundays and Holy Days. The Ordinals provided authorized rites for ordination of deacons, priests, and bishops, who would provide through time the sacramental ministries of the Church. The Primers — using simplified forms of the Daily Offices — enabled individuals and families to take part in an ongoing life of common worship when they were unable to attend services in their parish churches.

Background

Heiko Obermann, in his ground-breaking The Harvest of Medieval Theology,9 argues that what we call the Reformation was the result of a search for a more convincing answer to the question, “What must we do to be saved?” than medieval theology was able to provide. Obermann claims that, at heart, late medieval theology’s answer to that question was, “A loving God will not withhold His favor from one who does his best.” Which, of course, potentially leaves one, not with a sense of security, but with yet another question, “How does one know that one has done one’s best?”

In Obermann’s interpretation, this lack of security led the medieval Church to multiply the possible things that one could do to convince oneself that one has done one’s best. These might be to go on a pilgrimage, or buy an indulgence, or endow a chantry priest to say Mass for the repose of one’s soul. The doctrine of Purgatory — that the souls of the faithful who lived less-than-perfect lives went to a site of continued preparation for eventual transfer to Paradise, and that good deeds done in one’s name after one’s death could shorten one’s time in Purgatory — led to development of a practice that supported a large group of clergy entirely engaged in saying Masses for their deceased benefactors. All of these were, in addition, of course, to the more direct approach of loving God and loving one neighbor as oneself.

The Reformation, then — in addition to its objections to the commercialization of grace represented by the sale of indulgences — is about finding new ways of providing assurance of salvation. The post-Reformation Church of England provided one kind of an answer — that assurance came through a lifetime of participation in the public worship of the Church, as enabled by divine grace through the worship services scripted by the Book of Common Prayer and led by clergy ordained by bishops of the Church, clergy who, according to the Prayer Book had been given “power and commandment . . . to declare and pronounce to [God’s] people . . . the absolution and remission of their sins.” People baptized using the Prayer Book service received “the fullness of [God’s] grace,” were “grafted into the body of Christ’s congregation,” and set upon a life of continuing as “Christ’s faithful soldier and servant unto his life’s end.”

The first Book of Homilies taught that they were justified by faith, a faith into which they were baptized, then professed and claimed for themselves through repeating the Apostles’ Creed at every service of Morning and Evening Prayer, the Nicene Creed at every service of Holy Communion except on Christmas Day, the Epiphany, Saint Matthias, Easter Day, Ascension Day, Whitsunday, Saint John Baptist, Saint James, Saint Bartholomew, Saint Matthew, Saint Simon and Saint Jude, Saint Andrew, and upon Trinity Sunday, when the Creed of St Athanasius was used instead. Those who participated in worship according to the Book of Common Prayer on Sundays and Holy Days went through a process which included — on three occasions during the liturgical day — confession and absolution of their sins, leading to participation in the rite of Holy Communion that culminated in people being assured that those who had participated fully had been assured “therby of [God’s] favour and goodnes towarde [them], and that [they] be very membres incorporate in thy mistical body, whiche is the blessed company of al faithful people, and be also heyres through hope of thy everlasting kingdom.” This message of assurance was reaffirmed by the recitation of the Gloria in excelsis with its offering of “prayse,” blessing, worship, glorification, and thanksgiving to God.

The rites of Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, Ministry to the Sick, and the Burial Office brought the private and individual events in one’s life into the life of the corporate worshiping community. The promise of the first Book of Homilies that — in addition to the multiple liturgical occasions of assurance that one’s sins had been forgiven, that one was favored by God, a part of Christ’s mystical body, and an “heir through hope of [God’s] everlasting kingdom” — one possessed that “true and lively faith” that justified by doing good works, the “fruits of faith,” by repenting one’s sins, by living “in love and charity with [one’s] neighbors,” and intending to “live a new life . . . walking from henceforth in God’s holy ways.” The Homilies taught the importance of corporate worship, with its interactive narratives of confession and absolution, of profession of faith, of dialogue with God through the offering of praise and intercession, and its participation in the corporate actions of offering, blessing, breaking, and receiving the consecrated bread and wine, culminating in the Church’s ancient proclamation of “Glory to God on high.” So Cranmer’s — and the Church of England’s — answer to the question of how one could be confident of one’s salvation was described by, informed by, and enabled by corporate use of the rites of the Book of Common Prayer.

Context

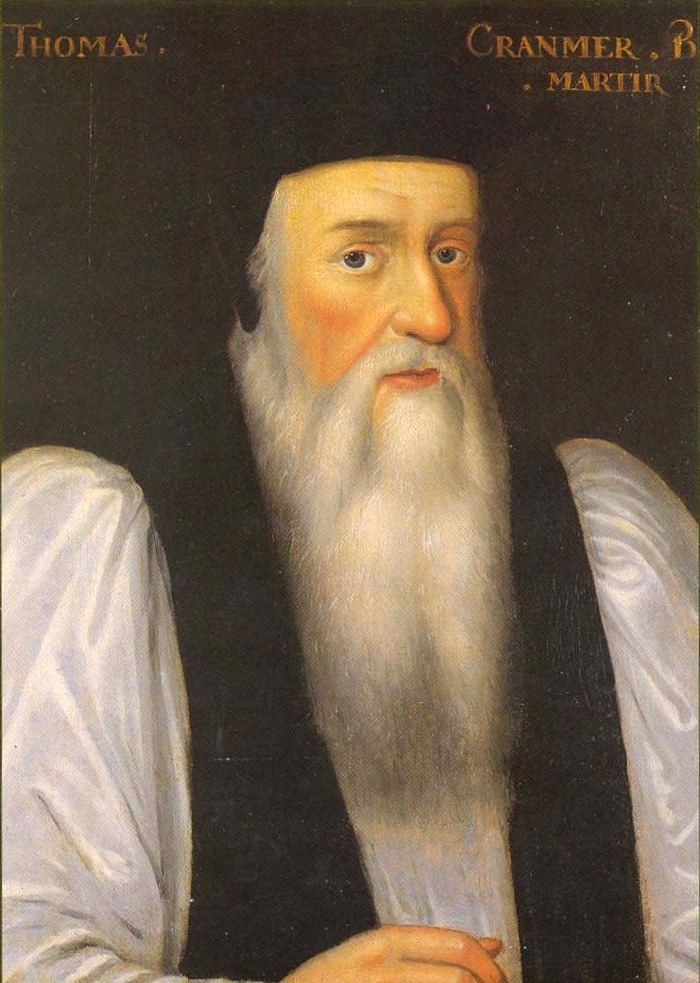

The English Reformation is generally regarded by historians as part of the Reformed — as opposed to the Lutheran — tradition of religious reform. One reason for this is that Thomas Cranmer, the architect of the English Reformation, was in personal communication with Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli, both of whom were living in England and serving as Regis Professors of Divinity at Oxford and Cambridge early in the reign of Edward VI. Such arguments often make the assumption that the writings of Bucer, Vermigli, and others provide a template for interpreting the documents and liturgies of the Edwardian Reformation, often to the point of ignoring the possibility that Cranmer might have listened but also come to his own conclusions. Indeed, the claim made by the Cathedral Project is that the performance of public worship, created by the Prayer book rites at the choreographed intersection of structured reading of the Bible, recitation of creeds, prayers, and anthems, and participation in the sacraments, was at the heart of Cranmer’s vision of a reformed Church of England. So its words, realized in the corporate action of public worship, are what we are to look to for a fuller and richer understanding of what he believed about the Christian faith.

Even though there was widespread support for the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) among Reformers, both those who remained in England under Mary and those who took refuge abroad in Geneva and other cities10, many of their younger followers would soon take the Reformed tradition in directions that proved increasingly divisive and — ironically, as we will see — restorative of features of the medieval Church that the early Reformers objected to. Their increasingly energetic affirmation of purity over inclusiveness, of sermons over sacraments11, of a restoration of the medieval focus on clergy as the primary actors in worship, of individual soul-searching over the corporate faith of the Church — a trend that continues to this day — demonstrates the difficulty the Reformers found in constructing a satisfactory, and enduring, answer to Obermann’s second question, the one about how one knows one has done one’s best.

The tendency among historians has been, anachronistically, to conflate the later Reformed movement’s emphasis on predestination and its objections to the Book of Common Prayer into the positions of Cranmer’s Reformed advisors of the 1540’s and 1550’s and Cranmer’s response to their council; hence, we get support for the legend that Cranmer, had he survived Mary’s reign, would have abandoned episcopacy and created a third version of the Book of Common Prayer that would have looked more like the Presbyterian Book of Church Order than his own Prayer Book. 12 Our project assumes, of course, that — although Cranmer’s views on the need for religious reform evolved over time — his vision reached its fullness and completion in the reform program he put into practice in the reign of Edward VI.

As a result of the approaches most church historians take, however, much of the discussion about the post-Reformation Church of England is framed by the question of what kind of church it was, or was intended to be, or would have become, if Edward VI had lived longer, or if Queen Elizabeth I had not intervened, or if William Laud had never become Archbishop of Canterbury. This pursuit of the “real” Church of England, and concomitant visions of what that “real” Church of England would have looked like have a way of structuring our readings of the past and of the people who inhabited it. In the case of John Donne, for example, in my career as a scholar of early modern English literature, we have had the Catholic Donne, the Protestant Donne, the Calvinist Donne, and the anti-Calvinist Donne, as well as the apostate Donne, the devout Donne, and the opportunistic Donne, not to mention all the other Donnes that shifting interpretive frameworks have enabled us to consider. 13

Defining the Church of England

As the distinguished historian of the Reformation Diarmaid MacCulloch has pointed out, the labels that have emerged to describe the religious traditions that emerged out of the various European rejections of papal authority in the 16th century “have a tendency to give a premature precision to people’s outlooks at a time when new religious identities were only painfully and gradually being created.”14 The difficulty thus created is inherent even in the simplest of terms — the dichotomy “Catholic vs Protestant.” That dichotomy is troubled by changing definitions of what constitutes the meaning of these terms. If the definition of the term “Protestant” is simply that it means anyone or any group that rejects the authority of the Bishop of Rome, then the Church of England was Protestant from the Act of Supremacy of 1534 and remains so today. This would be the case even if the Church of England had remained a church that worshipped in Latin, maintained the monastic system, and perpetuated a celibate priesthood. So, historians who argue, as did Tessa Watt, that for a time the Church of England had only “a patchwork of beliefs,” and by 1600 was still “distinctively ‘post-Reformation’ but not thoroughly Protestant,” have taken sides in a debate not of their making and constructed a definition of “Protestantism” for themselves more in line with the views of Puritan dissenters than with the historical record; in the process, they overlook the kind of church the Church of England was set up to be and actually turned out to be. 15

One complicating factor in the development of the Church of England’s identity is, of course, the period of Mary’s reign from 1553 until her death in 1558, when the authority of the Bishop of Rome was acknowledged once more. Yet one can also argue that that the “Catholic” status of the Church of England in this period does not mean that it once again became identical to the medieval Church of England. Some of the changes wrought by the Henrican and Edwardian reigns — the abolition of the monastic system, for example — could not be undone. Nor was the Catholic Church to which Mary returned the Church of England itself unchanged by the Reformation. After all, by the beginning of her reign the Council of Trent had completed two of its three sessions.

A National Church

Framers of a reformed Church of England faced a challenge unique among European nations. Unlike the German dukedoms or the Swiss city-states, the English needed to create a national church, a Church for millions rather than thousands, so, as Lucy Wooding has put it, the English Reformers sought “historical sanction and continuity” in their “need to fashion a form of Elizabethan Protestantism that was not just a protest movement but a framework for a state church.” 16 Hence their consistent appeal not only to scripture but to the Patristic Age as well.

As a result, the early English Reformers would claim that their Church was not simply a better alternative to Roman Catholicism but in fact the true Catholic Church, in continuity with the Church of the Apostles and the Fathers, while Rome was the AntiChrist. Or, as Edmund Spenser imagined it, Ecclesia Anglicana was the offspring of St George (his Red Cross Knight) and Una (the Truth), under the gracious shepherding and protection of Elizabeth I, Gloriana, the Faerie Queene. So Spenser describes the wedding of the Red Cross Knight and his beloved Una —

His owne two hands the holy knots did knit,

That none but death for euer can deuide;

His owne two hands, for such a turne most fit,

The housling fire did kindle and prouide,

And holy water thereon sprinckled wide;

At which the bushy Teade a groome did light,

And sacred lampe in secret chamber hide,

Where it should not be quenched day nor night,

For feare of euill fates, but burnen euer bright.

Then gan they sprinckle all the posts with wine,

And made great feast to solemnize that day;

They all perfumde with frankincense diuine,

And precious odours fetcht from far away,

That all the house did sweat with great aray:

And all the while sweete Musicke did apply

Her curious skill, the warbling notes to play,

To driue away the dull Melancholy;

The whiles one sung a song of loue and iollity.

During the which there was an heauenly noise

Heard sound through all the Pallace pleasantly,

Like as it had bene many an Angels voice,

Singing before th’eternall maiesty,

In their trinall triplicities on hye;

Yet wist no creature, whence that heauenly sweet

Proceeded, yet each one felt secretly

Himselfe thereby reft of his sences meet,

And rauished with rare impression in his sprite.

Great ioy was made that day of young and old,

And solemne feast proclaimd throughout the land,

That their exceeding merth may not be told:

Suffice it heare by signes to vnderstand

The vsuall ioyes at knitting of loues band.

Thrise happy man the knight himselfe did hold,

Possessed of his Ladies hart and hand,

And euer, when his eye did her behold,

His heart did seeme to melt in pleasures manifold.17

The Elizabethan Settlement of Religion in 1559, of course, reinstated the basic elements of the Edwardian Reformation, with slight variations, chief among them the revision in the Words of Administration of consecrated bread and wine in the Communion Service, achieved by combining sentences from both the 1549 and the 1552 Prayer Books. In addition, the requirement for use of Erasmus’ Paraphrases on the Gospels and Acts was dropped, the Forty-Two Articles were condensed into Thirty-Nine Articles, and a second Book of Homilies was added to the first. The key liturgical change was, of course, the addition of the words of institution from the 1549 Prayer Book (“The Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ which was given for thee, preserve thy body and soul into everlasting life” and its companion for the administration of the cup) to the words of institution from the 1552 Prayer Book, thus dramatizing the point that the language of the presence of Christ in the bread and wine finds meaning in relationship to the action within which the elements of Communion are offered, blessed, distributed, and received.

This means that everyone in England from the time of the Act of Supremacy was Protestant by default, so that claims that England had a “Long Reformation,” or that much of England remained Catholic long after 1534 reflect either the lumping of a wide variety of ways of being Protestant into a single meaning that obscures differences or that artificial lines of distinction between “Protestant” and “Catholic” identities are being created ex post facto and applied retroactively in ways that often obscure rather than clarify what was actually happening in early modern England. Since the character of any complex living organization changes over time, and so did the Church of England. To speak of there being a “Long Reformation” suggests that one has a specific idea of what a “reformed” Church of England would be like, in terms of which the Church of England was not reformed until it fit that definition. 18

So we are far better if we approach the history of the post-Reformation Church of England with attention to what did happen, in terms of an unfolding process, honoring some aspects of Medieval tradition while rejecting others, influenced by continental developments, but still best understood on its own terms rather than forced to fit into the categories of other religious and theological traditions. We especially need to avoid assuming that the post-Reformation Church of England is defined by one or another of the sides taken up in the various theological debates that took place among some of its leaders and some of their followers. Instead, we need to look to its official documents and the corporate religious life they enabled, and to its defenders against its opponents.

Corporate Unity versus Individual Destiny

The conventional story of the Reformation has it beginning in Luther’s Germany, then spread across Europe, developing new centers of Protestant thought in Zurich, Geneva, and other European cities. The European Reformation began as a protest against features of the medieval Church, hence “Protestant” and “Protestantism” became names for those who protested and the movement they created in protest. Issues that absorbed the attention of the protestors included ways in which the Medieval Church had turned the sacrament of the Eucharist into an action performed by the priest before an essentially passive congregation instead of the communal and participatory rite that Cranmer and his followers found in the writings of the Patristic Age.

Soon, however, simple dichotomies began to break down as Protestant groups found it necessary to move from reaction to affirmation, by beginning to formulate systems of belief and forms of practice to define themselves as stand-alone religious traditions, in contrast both to the medieval Catholic church and to other developing Protestant groups. At this point, things begin to get complicated, as do questions of nomenclature. As far as Englishfolk still loyal to Rome were concerned, the Church of England was surely Protestant, but to increasingly more radical followers of this or that continental Protestant group or leader, the Church of England was still too Catholic. The challenge we face is in recognizing what is distinctive about the Church of England as it developed, recognizing the extent to which it might, from one perspective, be seen as Protestant but from other perspectives be seen as what just as accurately might be termed an eccentric Catholicism.

Luther’s original formulations of a Protestant theology offered his interpretations of belief on issues at the heart of his concerns with the Medieval church. This set of issues — including justification by faith, the authority of scripture over tradition, the priesthood of all believers, worship and scripture reading in the vernacular, and the number and meaning of the sacraments — established an agenda for a growing number of theologians. So Luther and his followers’ response to the question of “What must we do to be saved” was based on a doctrinal premise — that we are not justified by our works but by our faith, that the heart of Christianity is found in Paul’s claim in his Epistle to the Ephesians, that “by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: Not of works, lest any man should boast.”

Yet it quickly became apparent that the more one relied on interpretations of scripture to order the common life of Christians, the more diverse those interpretations became. Luther challenged the Medieval Church on the issue of sale of indulgences in 1517; by 1524, Zwingli and his followers were in conflict with Luther and his followers over differing interpretations of what constituted the faith that justifies, of the role of good works, and especially of the meaning of the Eucharist, or Holy Communion. By the 1530s, John Calvin’s distinctive interpretations of these issues had found its own set of devotees, all within a scant 20 years from Luther’s original challenge to the Medieval Church. So the spirit of reaction and re-formation seems to have been built into Protestantism from the beginning, leading to an increased fragmentation of Protestant identity, with the number of Protestant denominations, even now, seemingly increasing by the day. 19

One way of thinking about these developments is to return to Obermann’s point about the Reformation itself being about dissatisfaction with the Medieval Church’s answer — or collection of answers — to the question of what must one do to be saved. If we are saved by faith, through grace, and if the Medieval doctrine of the sacraments as conduits of grace is undermined as part of the effort to distance the new Protestant churches from the consequences of the Medieval Church’s belief in transubstantiation, then the progressive reliance of the Reformers on the doctrine of predestination — for Luther, God’s predestination of the elect is important; for Calvin, it is essential; for Calvin’s followers like Theodore Beza, it becomes overwhelmingly central to the understanding of Christian teaching — can be seen as a sign of the difficulty they, too, faced in arrving at an enduringly powerful and broadly acceptable answer to this question.

Throughout the evolution of Reformed belief and practice is a growing attention to the inner life, the relationship of each individual believer to God. Timothy Rosendale explores well the paradoxes and complexities of this growing emphasis among Protestants on the inner life of the individual in his discussion of assurance considered outside the ongoing life of the Christian community. On the one hand, for Puritans, “[t]he inscrutable arbitrariness of God’s electing choice, while for some a source of terror, is also paradoxically the central source of soteriological comfort, isolated and insulated from the sinful vagaries of human will and action. Because God’s will is eternal, effective, and unchanging, salvation is absolutely guaranteed to the elect. As Luther put it to Erasmus, “I should not wish to have free choice given to me,” because then “my conscience would never be assured and certain” that I had done enough; but with everything in God’s hands, “I am assured and certain” of my salvation and glory.” On the other hand, “not everyone asserted or linked the two. . . directly and confidently . . . ; while grace is a source of comfort for all Christians, as we have seen, Christians have long disagreed on the degree of that grace’s hegemony. . . . Even the Calvinist 1646 Westminster Confession hedges a bit on the question of assurance, saying that “such as truly believe in the Lord Jesus, and love him in sincerity, endeavoring to walk in all good conscience before him, may in this life be certainly assured that they are in a state of grace, and may rejoice in the hope of the glory of God.” So, for all the Reformers came the moment when even their multiplying of possibilities for finding confidence in their salvation were found wanting, or as Rosendale puts it, “Assurance is not a sine qua non of election, but a kind of second blessing, given to some but not all.” 20

Ironically, in the evolving Reformed tradition, the clustering of Protestant groups around individual theological voices, the multiplication of Protestant theological traditions, and the collapse of traditional forms of Christian worship into the defining Protestant act of preaching recreated in the Puritan Minister the authority of the Medieval priesthood. The Catholic priest was a man set apart because he could work the miracle of transforming bread and wine into the literal Body and Blood of Christ; the Protestant preacher was a man set apart because he could, with his words, work the miracle of evoking the experience of conversion in the hearts of his listeners. In both cases, the ordained minister was the central actor, performing the role of the Man of God before a passive congregational serving as his audience.

One further sign of this reinvention of the clergy caste is the way in which proposed Puritan alternatives to the Book of Common Prayer reduced the role of the laity in public worship. All the various liturgies in the Book of Common Prayer include the active participation of all members of the congregation, whether this be through call-and-response interchanges (“The Lord be with you./And with thy Spirit”) or corporate recitations of prayers, confessions, canticles, and so forth. Puritan alternatives, offered in the late 16th century in books such as A booke of the forme of common prayers, administration of the Sacraments, &c. agreeable to Gods Worde, and the vse of the reformed Churches (1587)21 delete such interchanges and other signs of active congregational participation in favor of lengthy prayers delivered by the minister. Other differences indicating important theological distinctions include prayers of confession without texts for absolution, absence of of lectionaries for guiding public readings of scripture, abandonment of any of the historic Creeds, emphasis on the sermon as the essential reason for gathering listeners,22and a communion service without a recitation of any of the Biblical Institution Narratives of the Last Supper. As a result, the essential passivity of the medieval congregation was once more reaffirmed.

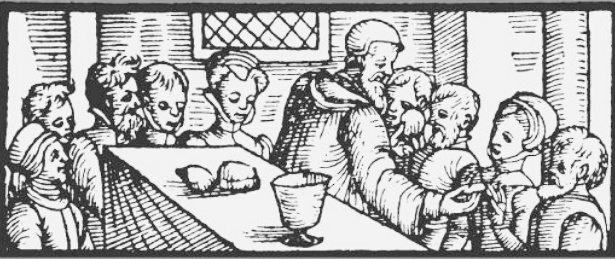

As we will see, in Cranmer’s liturgical scripting all members of the community have their roles and their voices. This is especially visible in Cranmer’s recasting of the rite of Holy Communion, where the celebrating priest is not the unique holy man, but the coordinator and enabler of the liturgy, the “work of the people.” He is not the only active person in the service, nor are his congregation merely the passive observers of his actions. All participate, their different roles uniting in the one corporate action. 23

The answer to the question of how we know if we are saved that was provided by Cranmer and his colleagues was, of course, that assurance comes through participation in the corporate, public life of the Church as enabled by the hierarchy of the ordained ministry and use of the Book of Common Prayer. The individual believer is fulfilled in the faith through participation in this life of corporate worship. To use the words of Peter White, the theology of the Church of England was “neither oppressed by a doctrine of total depravity nor so obsessed with the dangers of Pelagianism that it is afraid to admit the co-operation of the will with grace.” 24.

In Cranmer’s view, justification comes by faith through grace; while God is certainly free to bestow grace by other means, grace comes through the sacraments, through participation in Baptism and Holy Communion, in living the Christian life, including, tangibly, learning the texts folks needed to participate in corporate worship (especially the Creeds, the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer); when they know them, and the contents of the Catechism, they will be confirmed by their Bishop; they will be taught the activities of Christian living and inspired to do so through preaching; they will learn to express their faith through the “fruits of faith,” of good works of love and charity toward their neighbors; they will discover through participation in Holy Communion that they are the “mystical” Body of Christ, the “blessed company of all faithful people”; they will be married and have their children baptised in Church; they will be ministered to in their illnesses by their local vicar; they will die “in sure and certain hope of resurrection to eternal life.”

A Pragmatic Universalism

Hence, the best definition of the theology at the heart of English religious life coordinated by the Book of Common Prayer is that it was a pragmatic universalism.25. For the Church of England, faced with the challenge of sustaining a truly national church and the opportunity, through reforming the body politic, of creating a true godly kingdom, the full doctrine of predestination — that God not only predestines the Elect but also the Damned — was inherently divisive. The signs of its divisiveness are evident in the host of theological controversies it spawned, all of which heightened the energy around the subject, and the repeated efforts of Elizabeth and James to restrain public inquiry into its endless complexities.26.

The career of John Cotton, the early 17th century priest who was the vicar of St Botolph’s Church in Boston, England, and a devoted student of Calvin and Beza, provides a useful example. During his tenure as vicar of St Botolph’s, Cotton lived out his beliefs by organizing a parish of the elect within St Botolph’s, much to the distress of his other parishioners, and of his Bishop. Cotton, of course, eventually left England to join the Puritan colony in Boston, Massachusetts, where the challenges of reconciling conflicting individual interpretations of reformed Christianity in the absence of an overarching vision of community and a structure for the adjudication of differences led to continued fragmentation of the Body of Christ. And so it goes; as of last count by the Center for the Study of Global Christianity (CSGC) at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, there are now over 41,000 Christian denominations.

Unity, Concord, Charity

In Germany and Northern Europe, reasons for the break with Rome were primarily theological, however much their social and political contexts influenced the ways in which the course of the Reformation played out. In England, however, the specific catalyst for the Reformation was pragmatic. England’s break with Rome was provoked by Henry VIII’s reaction to the Papacy’s refusal to grant him an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Initially, of course, Henry had responded negatively to Luther’s break with Rome; in the early 1520’s, his 1521 anti-Lutheran pamphlet Assertio Septem Sacramentorum or Defence of the Seven Sacraments earned him the title of title “Fide Defenso,” or “Defender of the Faith” from Pope Leo X. Beginning in the late 1520’s, however, Henry sought a papal dispensation so he could divorce Catherine and marry again to provide security for the Tudor dynasty by provision of a male line of succession.

By the early 1530’s, however, when Pope Clement VII refused to grant Henry’s request, the King chose the route of rejection of papal authority as a way to reach his personal and political goals of marriage to Anne Boleyn. This led to a series of legislative acts, most notably the Act of Supremacy, passed by Parliament in 1534, which officially severed the relationship between the Church of England and the Papacy by rejecting Papal authority over religious affairs in England and declaring Henry to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

After a brief return to acceptance of papal authority during the reign of Queen Mary (1553 – 1558), the Church of England’s separation from Rome was reaffirmed by the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559). Thus, the Church of England was, from its beginnings, a national church. That is, with the monarch as its Supreme Head (under Henry VIII and Edward VI) or Supreme Governor (under Elizabeth and all subsequent English monarchs) and with the English Parliament as the governing body whose acts separated it from Rome and established it as the national church, the Church of England encompassed the entire population of the English nation. As such, it was mandated by Crown and Parliament to consider that membership in the Church included everyone born in the country.

England’s version of post-Reformation Christianity would therefore be of necessity a very different kind of Church than that found in Zurich or Geneva, or even in Scotland, where Calvin’s distinctive form of Protestantism would thrive both theologically and in terms of church organization. In the 1530’s, the population of Geneva was just over 20,000, while the population of England was over 3,000,000. The scale of territory, the size of the population, and the inevitable range of religious experience that would be required to bring meaning to such a diverse population, dictated that the transformation of a nation, rather than a regional dukedom as in Luther’s Germany or a city-state as in Switzerland or other parts of Europe, into a state church would pose a significant challenge.

Thomas Cranmer, Henry’s Archbishop of Canterbury and chief architect of the post-Reformation Church of England, was influenced in his theological development by Luther, whose Germany he visited in 1532, then, as we have already noted, by Philip Melancthon, Martin Bucer, and Peter Martyr Vermigli (in the 1540’s, Bucer and Vermigli both lived in England, Bucer serving as the Regius Professor of Divinity at the University of Cambridge and Vermigli serving as Regus Professor of Divinity at Oxford). Yet Cranmer’s program for the transformation of England from a nation Protestant only in its rejection of papal authority and its abolition of the monastic system into a nation Protestant in that it created a fully-articulated national church that would transform its Catholic predecessor would turn out to be a program that was pragmatic rather than dogmatic, liturgical rather than improvisational, and sacramental rather than rhetorical.

The recently-documented existence of transnational Anglo-Hellenic networks in place from the early 1520’s, visible in the English Reformers’ use of Greek texts from the Patristic Age and their contact with contemporary Greek visitors to England. 27 help us understand the models of non-Roman Church organization and identity available to Cranmer and his supporters. Like Orthodoxy, the Church of England turned out to be a Church grounded in scripture and the writings of the Church Fathers, episcopal in polity yet independent of the Papacy, and identified as English both in language and in national identity.

While some historians lament the absence of a spokesperson for the reformed Church of England recognizable on the model of Luther or Calvin, the reality is that the major body of theological writing for the reformed Church of England existed, hiding in plain sight, because it took the form of scripts for worship rather than elaborate formulations of belief. As David Griffiths has recently put it — arguing that the Church of England has always had “its own distinctive ethos” —

The liturgical genius of Thomas Cranmer ensured that its ethos found its best expression in the prayer-book: for a written liturgy can express the mind of a church more subtly and flexibly, and hence more permanently, than any set of doctrinal formulations.28

Cranmer’s program of reform, rolled out during the reign of Edward VI, defined the emerging Church of England as foregrounding the gathered community of the nation, parish by parish, diocese by diocese, province by province, and the corporate life of faith which its basic documents made possible. This universality of membership was reflected in the national legal system by such features as the requirement that every child born in the country be presented for baptism in the local parish church within 4 days of its birth and that everyone in the country was required to attend worship services in one’s parish church every Sunday and Holy Day, and receive Communion there at least 3 times a year, and always at Easter. 29

A Developing Vision

Cranmer produced two editions of the Book of Common Prayer during the reign of Edward VI. Each of these books was introduced into the worship life of the Church of England on auspicious days. The first Prayer Book was formally put into use on Whitsunday (the Feast of Pentecost) in 1549; the second was introduced on an equally auspicious day, the Feast of All Saints (All Hallows Day) in 1552. The first of these days was clearly chosen with care by Thomas Cranmer, because it enabled him to locate this transformation of worship in the English Church in the context of biblical precedent. By choosing Whitsunday, the Feast of Pentecost, as the day to inaugurate use of the Book of Common Prayer in wide public worship, Cranmer was able to stage the event as a repetition of the first Pentecost.

On that day in 1549, as congregations whose clergy had acquired a copy of the newly-printed Prayer Book took part in the service of Holy Communion, they heard as the Epistle for the Day the account from Acts about how – fifty days after Easter — when Jesus’ followers were “all with one accord together in one place . . . they were all fylled with the holy goost, and beganne to speake with other tonges, euen as the same [spirit] gaue them vtteraunce. . . . . . When thys was noysed aboute, the multitude came together, & were astonnyed, because that euery man hearde them speake with his awne langage. 30

As this happened in Jerusalem, fifty days after the first Easter, so, there, in the England of 1549, it was happening again, also fifty days after Easter, but now in cathedrals and churches across the land. So, on that day in June, the Reformers could say that what is happening was a renewal of the work of the Holy Spirit, a reconnection of the Church of England in 1549 with the church of Jesus’ early followers.

The second of Cranmer’s Prayer Books was officially put into use on All Saints’ Day in 1552. If the first of Cranmer’s Prayer Books was chiefly about transforming public worship into the “language understanded of the people,” the second one was chiefly about performing the liturgical enactment of the gathered community at worship as the Body of Christ on earth. Or, as Cranmer’s Collect for All Saints’ Day puts it,

Almighty God, which hast knit together thy elect in one Communion and fellowship, in the mysticall body of thy Sonne Christ our Lord: grant us grace so to follow thy holy Saints in all vertuous and godly living, that wee may come in those unspeakable joyes, which thou hast prepared form that unfainedly love thee, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Fortunately, we have an account of the introduction of the 1552 Book of Common Prayer in St Paul’s Cathedral:

Item on [Alhallows] day began the boke of the new series of bred and wyne in Powlles, with alle London, and the byshoppe [Nicholas Ridley] dyd the servis hym-selfe, and prechyd in the qwere at the mornynge servis, and dyd it in a rochet and nothynge elles on hym. And the dene with alle the resydew of the prebentes went but in their surples and lefte of their abbet [hoods] of the universtye; and the byshope prechyd at after-none at Powlles crosse, and stode there tyll it was nere honde v. a cloke, and the mayer nor aldermen came not with-in Powlles church nor the craffted as they were wonte to doo, for be-cause they were soo wary of hys stondynge.31

In his discussion of Anglican spirituality, Harvey Guthrie got the Church of England about right when he said that, from the beginning, it was neither about adhering to a particular theological formulation of the faith, like Catholics or Lutherans or early Calvinists, or about demanding a personal experience of conversion or a private conviction of one’s election, like the Calvin’s followers in the Reformed tradition. Instead, it was a pragmatic tradition, a tradition that was corporate, liturgical, and sacramental, in which people are identified as members by being baptised, by taking part in the liturgical life of the corporate body, by participating in the celebration of Holy Communion, by observing the Church’s feasts, fasts, and ordinances, by shaping their lives by the rhythms of confession, absolution, communion, ever more seeking to live in love and charity with their neighbors, as “very members incorporate in [Christ’s] mystical body which is the blessed company of all faithful people.” 32

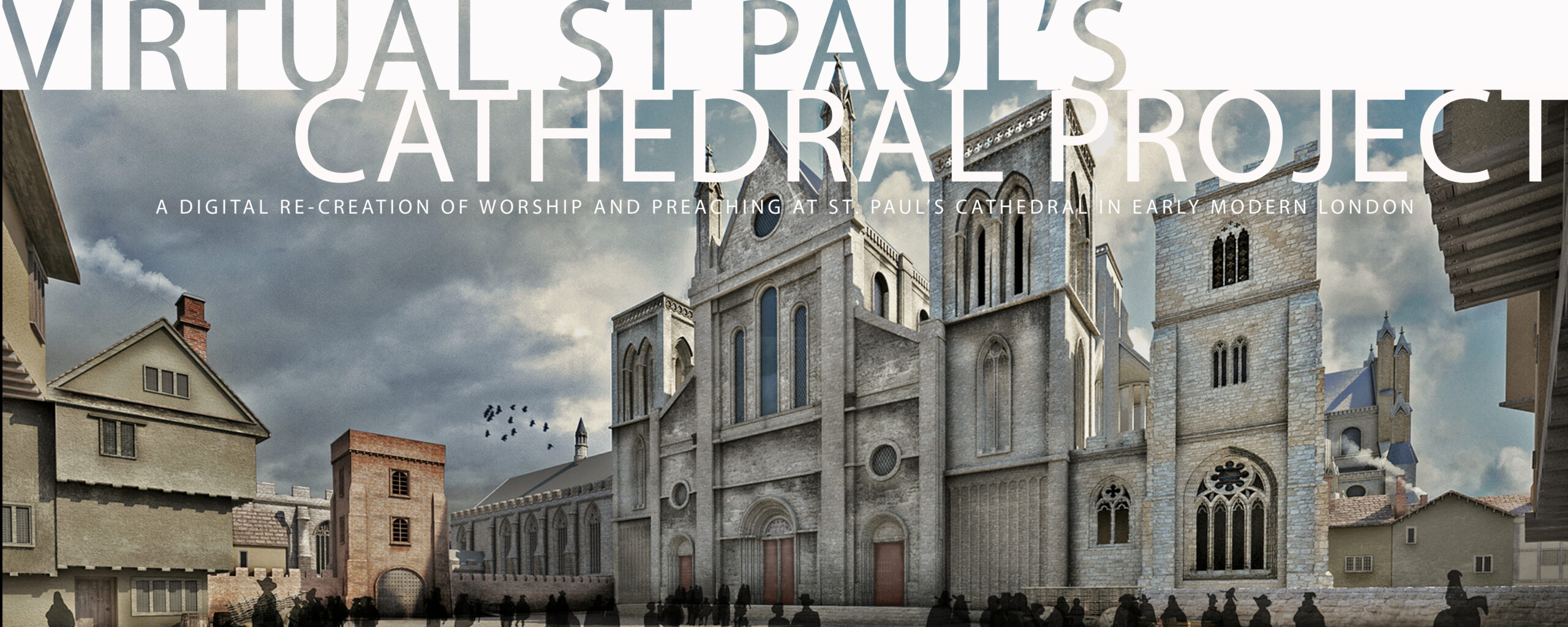

St Paul’s Cathedral, the East Front. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

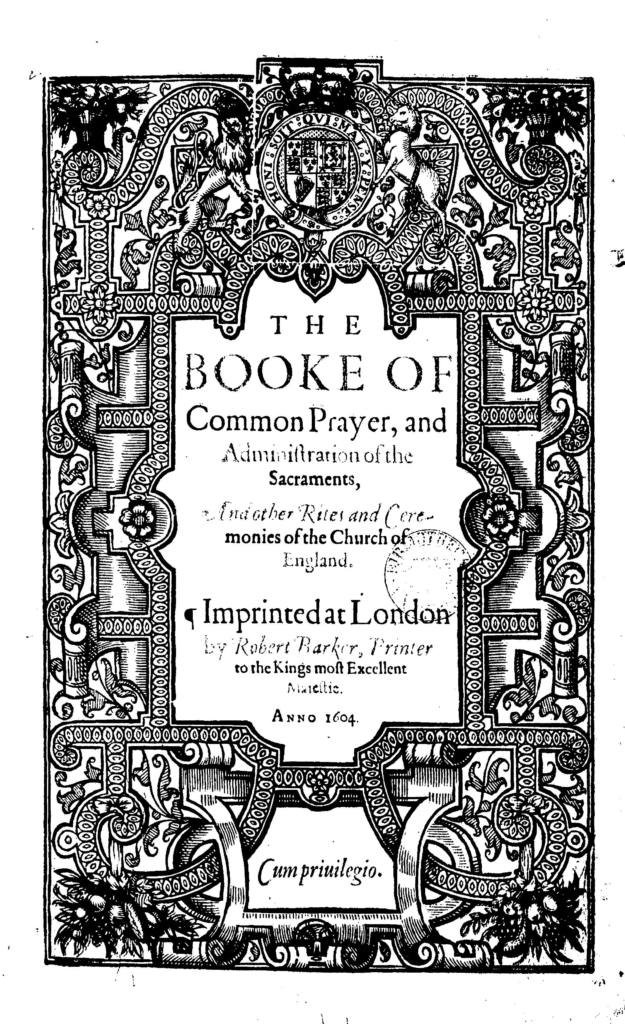

Englishfolk who, whatever their own personal beliefs or understandings might be, were asked to comply with the terms of the Elizabethan Settlement in weekly church attendance, in being married by their parish priest, having their children baptized, and receiving the bread and wine of Holy Communion at least 3 times a year. 33Their corporate life was enabled by use of texts every parish church was required to purchase and to use — the Book of Common Prayer (1549/1552; 1559; 1604) and the Great Bible (1539); their understanding of the reformed faith was enlightened through use of the sermons in the Book of Homilies (Book One, 1547; Book Two, 1563 ) and the Articles of Religion (42 in 1553, 39 in 1571). At the beginning, the official perspective on scripture came not from Luther or one of the other continental reformers, but from Erasmus, whose Paraphrases on the Gospels and Acts was also one of the original “Great Books” of the Edwardian Reformation. 34

A Congregation of Unity Together

The genius of Cranmer’s reform program was in its combination of a common worship life with freedom to interpret the meaning of its language and practices for oneself. Queen Elizabeth I is reported to have said, “I have no desire to make windows into men’s souls.” So the response of the reforming Church of England to the question about one’s confidence about one’s relationship with God comes not through an individual’s ascent to a distinctive doctrinal formulation or to an individual’s conversion from unbeliever to believer (captured nicely some centuries later in John Wesley’s description of feeling his “heart strangely warmed” when someone spoke to him of “the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ”), but in a life-long immersion in the life of a community formed by corporate worship using the Book of Common Prayer. The rites of the Prayer Book created for ordinary parishioners provided, in the words of David Bagchi, “a daily and weekly framework of comfort and assurance.”35

Cranmer’s Sacramental Theology

Cranmer’s Prayer Book and its ancillary documents from Edward’s reign use the language of the continental Reformers, but reinterpret them as components of the gathered community’s life of faith. While the Articles of Religion affirm that “we have no power to do good works . . . without the grace of God,” we are assured by the Book of Common Prayer that at baptism we receive God’s grace, so that we are “regenerate . . . with thy Holy Spirit, [received] as [God’s] own child by adoption,” and incorporated into “thy holy congregation,” so that, according to Article XXVII of the Thirty-Nine Articles, “the promises of the forgiveness of sin, and of our adoption to be the sons of God by the Holy Ghost, are visibly signed and sealed, Faith is confirmed, and Grace increased by virtue of prayer unto God.”

The Articles also affirm that we are justified by faith and not by works; the Book of Common Prayer enables parishioners to reaffirm their faith, daily, over and over, using the historic Creeds of the Church. The Articles affirm human sinfulness; the Book of Common Prayer provides opportunities at Morning and Evening Prayer and at Holy Communion for the congregation to confess its sins, corporately, and to be absolved of them. The Book of Homilies asserts that while we are justified by faith and not works, the faith that justifies us is a “true and lively faith” that reveals itself in good works, in the actions of a life, as the Prayer Book puts it, of “love and charity with our neighbors . . . walking from henceforth in [God’s] holy ways.” So, we are advised that we are to look to our works, look to how we participate in the social world around us, rather than following the Puritans deeper and deeper into our individual selves.

The goal of corporate worship according to the Book of Common Prayer is ever deeper engagement with leading a Christian life, as described in the Communion Service’s invitation to reception:

You that do truly and ernestly repente you of youre sinnes, and be in love, and charite with your neighbors and entende to lede a newe lyfe, folowing the commaundementes of God, and walkynge from hence furthe in his holy waies: Draw nere and take this holy Sacrament to your comforte, make your humble confession to almighty God, before this congregation here gathered together in his holye name, mekely knelynge upon your knees.

An ongoing process of repentance and absolution, together with living charitably in community, and receiving the sacrament of Holy Communion brings one comfort, identity, and purpose, because, through one’s participation in the the Communion one is assured that God shows “favor and goodness toward us,” that we are linked in this action with the faithful who have gone before, who are with us now, and with those who are yet to come, all “very members incorporate in thy mystical body, which is the blessed company of all faithful people,” and therefore “heirs through hope of thy everlasting kingdom.” The most telling change that Cranmer made in the service of Holy Communion in the 1552 Prayer Book was to locate the congregation’s reception of the bread and wine of Communion immediately after the priest’s recitation of Jesus’ Words of Institution, right after the congregation hears Jesus say, through the voice of the Celebrant, that “This is my Body,” “This is my Blood”; Do this in remembrance of me.”

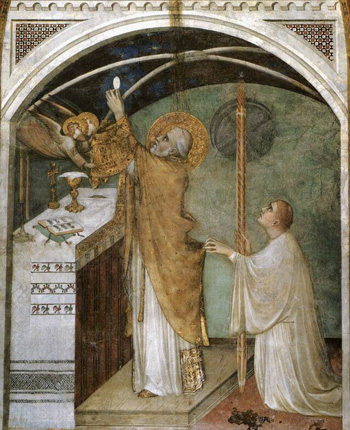

In the lived religion of the Medieval Church, worship centered on the moment when the priest elevated the consecrated host. Eamon Duffy has described eloquently how, when this elevation was preformed, members of the congregation would be alerted by the ringing of the Sanctus bells to direct their attention to the act.36 As multiple celebrations of Mass were taking place each day, congregants might wander around from altar to altar hoping to catch that moment several times, or position themselves to be able to see the elevation take place at more than one altar at the same time. The theology of the Mass echoed and emphasized this spatialization of the sacrament; Christ is present, corporally, in the bread held in the priest’s hands there, over there, apart from the congregation, which is here, and not there. Actually receiving the holy bread, the Body of Christ, making the transition from here to there, took extensive preparation shaped by participation in the sacrament of penance, and so was rarely done, perhaps only once a year even in the lives of the most devout layfolk.

In contrast, in Cranmer’s mature text of the Communion rite, the language of presence that so troubled the post-Reformation Churches is clarified; the meaning of the words “presence of Christ in the Holy Communion” comes from the experience of the congregation’s participating in the action of Jesus, to take the bread, to bless it, to break it, and to offer it to his disciples. In the Medieval Mass, Christ was physically present, after consecration, in the bread and wine of the Mass, apart from the congregation; in Cranmer’s Holy Communion Christ is present in the congregation’s action with the bread and wine, as the risen Body of Christ is recognized in the bread and wine as it is consumed by the Body of Christ, the gathered congregation. Or, as one of the late 16th century commentaries on the Prayer Book Catechism puts it, the “outward sign in this Sacrament” is “Bread and Wine, together with the actions of blessing, breaking, distributing and receiving, exercised in and about the same,” so the “inward, spiritual thing signified thereby is “The Body and Bloud of Christ, given us by God, and received of us by faith for the nourishing of our soules unto eternall life.”

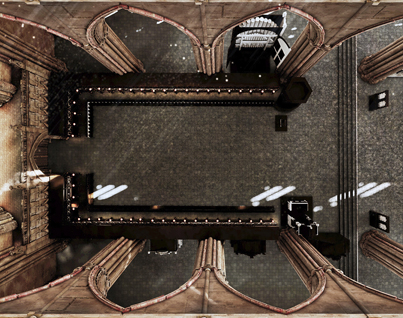

Cranmer’s understanding of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist thus linked of concepts of Christ’s presence in the bread and wine of Holy Communion to the temporal actions of the celebrant and congregation with the bread and wine of Communion, is made visible in use of what we would call free-standing altars, tables standing “in the body of the church, or in the chancel.” Here, Cranmer anticipates the language and practice of the modern Liturgical Movement, which led to modern use of free-standing altars in both Catholic and Anglican churches, and to documents such as the Agreed Statement on Eucharistic Doctrine of the Anglican/Roman Catholic Joint Preparatory Commission, which states in part

- Communion with Christ in the eucharist presupposes his true presence, effectually signified by the bread and wine which, in this mystery, become his body and blood. The real presence of his body and blood can, however, only be understood within the context of the redemptive activity whereby he gives himself, and in himself reconciliation, peace and life, to his own. On the one hand, the eucharistic gift springs out of the paschal mystery of Christ’s death and resurrection, in which God’s saving purpose has already been definitively realized. On the other hand, its purpose is to transmit the life of the crucified and risen Christ to his body, the church, so that its members may be more fully united with Christ and with one another.

- Christ is present and active, in various ways, in the entire eucharistic celebration. It is the same Lord who through the proclaimed word invites his people to his table, who through his minister presides at that table, and who gives himself sacramentally in the body and blood of his paschal sacrifice. It is the Lord present at the right hand of the Father, and therefore transcending the sacramental order, who thus offers to his church, in the eucharistic signs, the special gift of himself.

- The sacramental body and blood of the Savior are present as an offering to the believer awaiting his welcome. When this offering is met by faith, a lifegiving encounter results. Through faith Christ’s presence — which does not depend on the individual’s faith in order to be the Lord’s real gift of himself to his church — becomes no longer just a presence for the believer, but also a presence with him.

Thus, in considering the mystery of the eucharistic presence, we must recognize both the sacramental sign of Christ’s presence and the personal relationship between Christ and the faithful which arises from that presence. - The Lord’s words at the last supper, “Take and eat; this is my body”, do not allow us to dissociate the gift of the presence and the act of sacramental eating. The elements are not mere signs; Christ’s body and blood become really present and are really given. But they are really present and given in order that, receiving them, believers may be united in communion with Christ the Lord.37

This emphasis on the role of Holy Communion as constitutive of community in time and in Christ, as the community recollects and gives thanks for how God has acted, especially in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, celebrates both the community and the Christ who unites the separate individuals into one church, and looks forward to the anticipation of the future consummation of history and the eternal reign of the Messiah. Cranmer’s theology of the Holy Communion perhaps came from his study of St Augustine’s works, notably Augustine’s Sermon 272, in which Augustine tells his congregation,

“[Y]ou, therefore, are Christ’s body and members, it is your own mystery that is placed on the Lord’s table! It is your own mystery that you are receiving! You are saying “Amen” to what you are: your response is a personal signature, affirming your faith. When you hear “The body of Christ”, you reply “Amen.” Be a member of Christ’s body, then, so that your “Amen” may ring true! But what role does the bread play? We have no theory of our own to propose here; listen, instead, to what Paul says about this sacrament: “The bread is one, and we, though many, are one body.” [1 Cor. 10.17] Understand and rejoice: unity, truth, faithfulness, love. “One bread,” he says. What is this one bread? Is it not the “one body,” formed from many? Remember: bread doesn’t come from a single grain, but from many. When you received exorcism, you were “ground.” When you were baptized, you were “leavened.” When you received the fire of the Holy Spirit, you were “baked.” Be what you see; receive what you are.”

So, unlike Medieval Catholicism, which organized its public worship around the celebration of the Mass, with its offering of the sacrifice of Christ to God the Father with the goal of changing God’s mind about humanity, Cranmer’s Holy Communion was about reassembling the Church as Christ’s earthly Body, about changing the congregation’s mind about God, about furthering the Church’s role in Christ’s work of reconciliation through the Church’s work in the world, about building the True Christian Commonwealth. Even the Doctrine of Predestination (a topic very much in the air in the early 1500s and after) takes its meaning in relationship to the building up of the congregation as the Body of Christ. We are told, in Article XVII of the Thirty-Nine Articles, that the positive side of the Doctrine of Predestination is “full of sweet, pleasant, and unspeakable comfort’ to those who “walk religiously in good works” because “it doth greatly establish and confirm their faith of eternal Salvation to be enjoyed through Christ as because it doth fervently kindle their love towards God.” On the other hand, the negative side of the Doctrine of Predestination is to be avoided because “to have continually before their eyes the sentence of God’s Predestination, is a most dangerous downfall, whereby the Devil doth thrust them either into desperation, or into wretchlessness of most unclean living, no less perilous than desperation.” In this reading, the concept of Predestination, instead of simply the occasional use of a term in popular usage to support and encourage the faithful, is perhaps best put in the language of Peter Baro, “that God truly and without limit called all people to repentance, faith, and salvation. Consequently, God had predestined those whom he eternally foresaw would have faith in Christ while rejecting those who were foreknown to persist in sin. Thus no necessity was imposed on human wills. Election was eternal and immutable, but it was also conditional, the effect of divinely foreseen freely made human choices.” 38 Or, as Judity Maltby has put it, even to clergy to whom Predestination mattered, it was “a predestinarianism with such expansive edges that at every Prayer Book funeral service the deceased could be declared as among the elect.” 39

In other words, the overall health of the body politic as the Body of Christ provides the norm from which to evaluate and embrace or reject matters of doctrine or belief. This approach to defining the goals of a program of religious reform resulted in a collection of resources that enabled the corporate practice of the Christian faith as the hallmark of the English Reformation. The “Great Books” of the English Reformation provide resources for worship that intersect at the time of worship; the Book of Common Prayer provides the scripts for a process of public worship that then incorporates into the public performance of the Prayer Book Rites the structure of readings from the Great Bible and the model sermons from the Book of Homilies. These services incorporate the historic creeds of the Early Church, providing continuity between the worship life of the Church of England and the period of Christian history which the English Church understood to be normative. The Articles of Religion provide basic guidance about the terms of Clergy ordained by use of the Church of England’s Ordinal ensure that these worship services are conducted “decently and in good order.”

Post-Elizabethan Settlement Primers and Guides to the Church’s Catechism reinforce the centrality of public worship. As Harrison tells us, “In the afternoon likewise we meet again, and, after the psalms and lessons ended, we have commonly a sermon, or at the leastwise our youth catechised by the space of an hour.” So Christian education is located in the parish church, and conducted as an adjunct to evening Divine Service. The Primer of 1553 provides individuals and families with rites simplied from but essentially based on the Prayer Book’s Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer; as David Siegenthaler puts it, in the Primers, private devotion derives from “the corporate devotion of the whole church: . . . private prayer derives from corporate prayer and . . . the forms and concerns of private prayer and the forms and concerns of public prayer.” The official Catechisms of John Ponet, Bishop of Winchester (first published 1553) and Alexander Nowell, Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral (first published in 1570), are both based on the official Catechism of the Church of England; they both, in Siegenthaler’s words, promote the belief that personal morality and private sinfulness are to be seen primarily in the context of the their impact on the godly commonwealth, a subsuming of “individual godliness in an aggregate godliness.” 40

Context

This emphasis on the value of building up corporate unity had been present from the beginning of the Edwardian program of reform. In the Preface to the Book of Common Prayer of 1549, Archbishop Cranmer asserted its value when he declared that one purpose of this Book was the unity of the nation in prayer: “heretofore, there hath been great diversitie in saying and synging in churches within this realme: . . . Now from hencefurth, all the whole realme shall have but one use.” To the end that all may participate in “one use,” Cranmer declares that “all thynges shalbe readde and song in the Church, in the Englishe tongue, to the ende that the congregacion may bee thereby edifyed.” To this generation of English Reformers, the concept of “election” did not refer to an individual’s relationship to the eternal decrees of God, but, on the model of election provided by the Old Testament, to England as God’s elect nation. At the coronation of Edward VI, Cranmer heralded Edward as the “new Josias,” who would restore England to God’s favor through his reformation of the body politic.

Clearly, therefore, Cranmer’s goal in the creation of the Book of Common Prayer was not to do what Kenneth Stevenson has described as “embod[ing] a liturgy that put Reformation teaching (As though there were such a thing as a single version of “Reformation teaching”!) into praying words.” 41 Instead, it is to the Book of Common Prayer that one should look to understand Cranmer’s understanding of “Reformation teaching.” Cranmer’s goal was to create a liturgical structure that enabled the Church of England to be a truly national church, a pragmatic church, in which people are identified as members by being baptised and by taking part in the liturgical life of the corporate body, thus bringing the private dimensions of their lives into the life of the worshipping corporate community, living in love and charity with their neighbors, and dying “in sure and certain hope of resurrection to eternal life.”

In other words, the prayers of the Church come first, so that “as we pray, so do we believe, and as we believe, so do we live'” (or, in the Latin, “lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi”). Hence, the pastoral demands of a national church came first, not slavish allegiance to abstract theological formularies. 42

This pragmatic goal of national unity in matters of religion for the good of the entire nation as congregation thus became a distinctive emphasis of of the early years of Elizabeth’s reign. As Angela Ranson has recently pointed out, the Marian Exiles, whether they sequestered during Mary’s reign in Geneva or Zurich, on their return to England joined those who had stayed behind in fulfilling the promise of the Edwardian Reformation under the reign of Elizabeth. 43

In his early defense of the Elizabethan Settlement, John Jewel, who had been Cranmer’s secretary, chose to defend the Church of England against Catholic opponents not as much on doctrinal grounds as much as on the grounds that the English Church is united in what it does, together, and that what it does is what the true Church has done, always and everywhere. In his Apology of the Church of England, his defense of the Elizabethan Settlement,44and in Part II, especially, he repeatedly begins sentences with the phrase “We believe” to affirm the Church’s faith, as expressed in what Lancelot Andrewes would describe later as “One canon reduced to writing by God himself, two testaments, three creeds, four general councils, five centuries, and the series of Fathers in that period – the centuries that is, before Constantine, and two after, determine the boundary of our faith.”

It was members of the next generation of Calvinists who began to challenge the Church of the Elizabethan Settlement on the grounds that it was unBiblical. In the 1590’s, in the face of rising Puritan opposition to the Elizabethan Settlement, Richard Hooker would spend all eight volumes of the Of the Lawes of Ecclesiasticall Polity defending the Settlement and life of the national Church it sought to facilitate, devoting by far the most space (all of Volume V) to direct defense of the Book of Common Prayer. Seeking to persuade followers of Calvin’s distinctive version of Reformed Christianity that the Elizabethan Settlement met the needs of the English for a national Church, Hooker is polite about Calvin’s role as a reformer, but in the marginal notes to his copy of the Puritan Christian Letter of Certaine English Protestantes (1599), he speaks with a more personal voice. Calvin’s influence on Hooker’s Puritan opponents is so great, Hooker writes, that Calvin is a “boile that may not be touched.”

Historians tend to ignore the fact that Hooker, in the Lawes, is not so much neutrally describing the Church of England as an entity outside of himself but seeking common ground with his Puritan opponents so as to persuade thiem to accept the Church of England as it is rather than trying to refigure it to fit their own requirements. So his stance is at heart the stance of a persuader, a rhetorician, not a systematic theologian. He is overpolite about Calvin, is willing to describe the episcopate as esse, simply a workable part of the Church as it is, rather than a bene esse, a “good, or essential, part.” 45

Of course, some of Calvin’s followers were by then at the heart of the Established Church; in 1595, John Whitgift, then Archbishop of Canterbury, submitted the Lambeth Articles for adoption as an official doctrinal statement of the Church of England. Whitgift’s Articles take a hard, rather than a pragmatic, approach to the Doctrine of Predestination.46Whitgift’s Articles not only affirm both the negative and positive sides of predestinarian claims but also proclaim both a very pessimistic view of human nature and the belief that Christ died only for the Elect. So if Whitgift had been successful in getting them adopted as an official statement of the Church of England, Article XVII of the Thirty-Nine Articles would have had to be rewritten. On the other hand, early in the seventeenth century, the English delegates to the Synod of Dort would challenge the idea (which was also part of Whitgift’s Articles) that Christ died only for the elect. Among the specific reasons they gave for their belief that Christ died for the sins of the whole world were the facts that it was so stated in Article XXXI of the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion and repeated at every celebration of Holy Communion in the Prayer of Consecration.

Ian Green’s discussion of the contrast between the Church of England’s vision of the individual as important as part of the larger community and the inward life as supportive of, rather than superior to, the public and Calvin’s followers, with their emphasis on inward searching for signs of election is helpful here. In his Print and Protestantism in Early Modern England, Green describes Calvin’s English followers thus:

The consequences for the life of faith of the high Calvinist stress on the total depravity of man, election being irrespective of human merit, Christ having made a limited atonement (in effect), and the existence of different kinds of faith of which only one was saving, were considerable for those who were exposed to such teaching and grasped it thoroughly. It led to an insistence on the heart being not merely bruised but broken and reduced to what Perkins once called ‘a holy desperation’. It was the depth of this desperation and the evolution of new means of curing it — by providing detailed accounts of how to distinguish between different types of faith and between true believers and ‘drowsy professors’, lists of the ‘marks’ of those whose names were written in the Book of Life, and details of the techniques of introspective analysis which would help the elect to tell if they were on the right road to heaven — which helped to distinguish ‘godly’ writing from other English Protestants’ work. The difference of emphasis from official teaching here can be seen if we look at the teaching of the formularies written in the Edwardian and early Elizabethan periods, such as the Book of Common Prayer, short catechism, and homilies. There the elect were equated simply with those who believed, as God knew they would, so that membership of the elect was not crucial to the account of the life of faith contained therein.

According to Green, these formularies, along with a wide range of writings of this age, both Catholic and Protestant, and including the works of George Herbert, John Donne, Lancelot Andrewes, and Jeremy Taylor, “all demanded that the faithful look inside themselves in order to ‘acknowledge and confess’ their ‘mainfold sins and wickednesses,’ and ensure that they had a ‘lively faith’ (to be determined, according to the First Book of Homilies, by looking outside oneself to notice if one did good works, the “fruits of a true and lively faith”) and a ‘pure heart,’ were ‘truly and earnestly’ repentant for their sins and ‘unfeignedly’ believed in the holy Gospel. But they did not lay it down as a norm that the experience of sorrow for sin would be traumatic, or that those who were truly repentant could be distinguished readily from those ]#’who were not by certain infallible signs; and for assurance of salvation they urged the faithful to look to Christ rather than into their own hearts.” 47

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Tower. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

OUTCOMES

Worship using the Book of Common Prayer after the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion in 1559 gradually became a familiar practice, organizing the calendar, shaping the experience of Scripture and worship, so that, as Eamon Duffey puts it, “Cranmer’s somberely magnificent prose, read week by week, entered and possessed their minds, and became the fabric of their prayer, the utterance of their most solemn and their most vulnerable moments.” [7] Or, as William Harrison put it in his classic contemporary account of Tudor social life [8]), “the minister saith his service commonly in the body of the church, with his face toward the people” so “the ignorant doo not onelie learne diuerse of the psalmes and vsuall praiers by heart, but also such as can read, doo praie togither with [the priest]: so that the whole congregation at one instant powere out their petitions vnto the liuing God.”

Or, as Izaac Walton put it in his Life of George Herbert,

Mr. Herbert’s own practice; which was to appear constantly with his wife and three nieces—the daughters of a deceased sister—and his whole family, twice every day at the Church-prayers, in the Chapel, which does almost join to his Parsonage-house. And for the time of his appearing, it was strictly at the canonical hours of ten and four: and then and there he lifted up pure and charitable hands to God in the midst of the congregation. And he would joy to have spent that time in that place, where the honour of his Master Jesus dwelleth; and there, by that inward devotion which he testified constantly by an humble behaviour and visible adoration, be, like Joshua, brought not only “his own household thus to serve the Lord;” but brought most of his parishioners, and many gentlemen in the neighbourhood, constantly to make a part of his congregation twice a day: and some of the meaner sort of his parish did so love and reverence Mr. Herbert, that they would let their plough rest when Mr. Herbert’s Saint’s-bell rung to prayers, that they might also offer their devotions to God with him; and would then return back to their plough. And his most holy life was such, that it begot such reverence to God, and to him, that they thought themselves the happier, when they carried Mr. Herbert’s blessing back with them to their labour. Thus powerful was his reason and example to persuade others to a practical piety and devotion.48

The introduction of the first Book of Common Prayer in 1549 had led to popular uprisings in several parts of the country, including among the folks in the West Country, who proclaimed to Edward VI that “We will not receive the new service, because it is but like a Christmas game.” Indeed, their reaction to the introduction of the Prayer Book serves as a reminder that the Book of Common Prayer, even though its use in all churches across England was required by law, never made everyone happy. Dissatisfaction with the Prayer Book, which ebbed and flowed between 1549 and 1645, finally contributing to the outbreak of the English Civil War and to that January 4th, when Parliament passed the Ordinance that took away the Book of Common Prayer. But by the mid-1640’s, the people of the West Country felt differently about what was happening than their ancestors had in 1549. In this later case, they petitioned Charles I that he “eternize (as far as in you lies) [this] divine and excellent form of Common Prayer.” In this period of run-up to the Civil War, others joined them; the good folks of Cheshire added their praise, declaring that at least in Cheshire “scarce any Family or Person [who] can read, but are furnished with the Book of Common Prayer, in the conscionable Use whereof, many Christian Hearts have found unspeakable joy and comfort.”49

This immersion in the Lectionary-structured reading of Scripture, prayer, confession-and-absolution, and observation of the Sacraments therefore began to have its impact on the writings of clergy like John Donne and George Herbert, as well as on layfolk like Henry Vaughan. Here are a couple of examples.

Donne’s Devotions

Cranmer’s and the Elizabethan Settlement’s understanding of public worship as essentially corporate also found a voice in the 1620’s in the words, and work of John Donne, Dean of St Paul’s from 1621 to 1631. In his dramatization of the spiritual journey he documented in his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. Donne tells us, in the Third Expostulation of his Devotions that while he is “nayled” to his bed by his illness, he cannot be where God is, in Church, in the Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral, carrying out his role as priest and Dean in the regular round of daily and weekly services that marked the working life of the Cathedral.