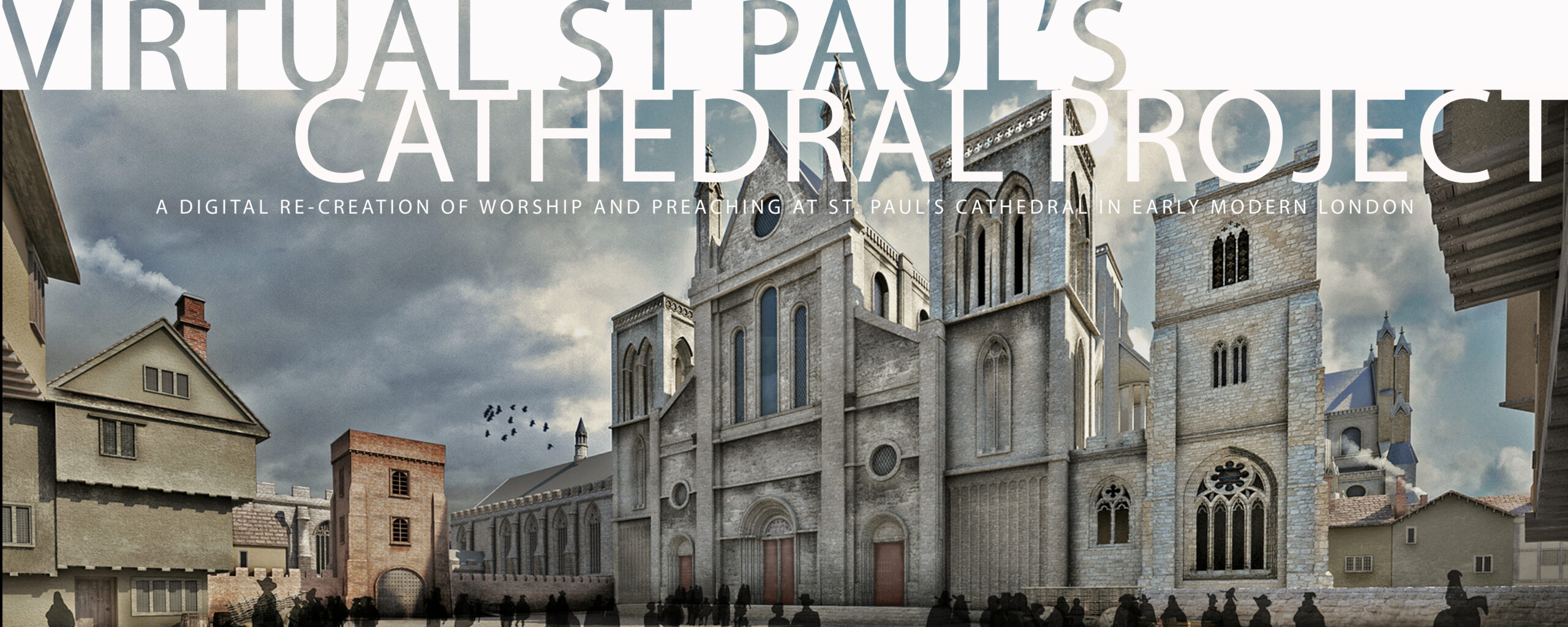

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project remains, inevitably, a work in progress. As such, the Visual Model represents a stage in that work. To bring together in one model the things we know or believe we know about the structures in Paul’s Churchyard requires drawing a line at some point in the process of our research. We have done this in the full knowledge that there is more to know, that new information will appear; indeed, we hope that our work will inspire other people to continue it by looking for new sources of information about the buildings inside Paul’s Churchyard.

Potential New Uses of the Model

Technology moves ever onward, especially in the area of display. During the years of developing the Virtual Paul’s Cross and Virtual Cathedral Projects, this has been especially true. Each new development opens the possibility of new uses for our visual models.

Augmented Reality

One potential use would be to create an augmented reality version which would enable the user to move around Paul’s Churchyard with a viewing device that would enable the user to see our model from the perspective of the position in which the user happened to be standing.

For example, one could stand along and see Wren’s Cathedral in front, but see on the viewing device our model of St Paul’s and Paul’s Churchyard from the same position, (The two images below do not line up exactly, but one can still get a sense of the experience that an augmented reality use of the model might provide. )

With an augmented reality version of our model, the user could wander around Paul’s Churchyard and inside the Cathedral itself, comparing past and present along the way.

Virtual Reality

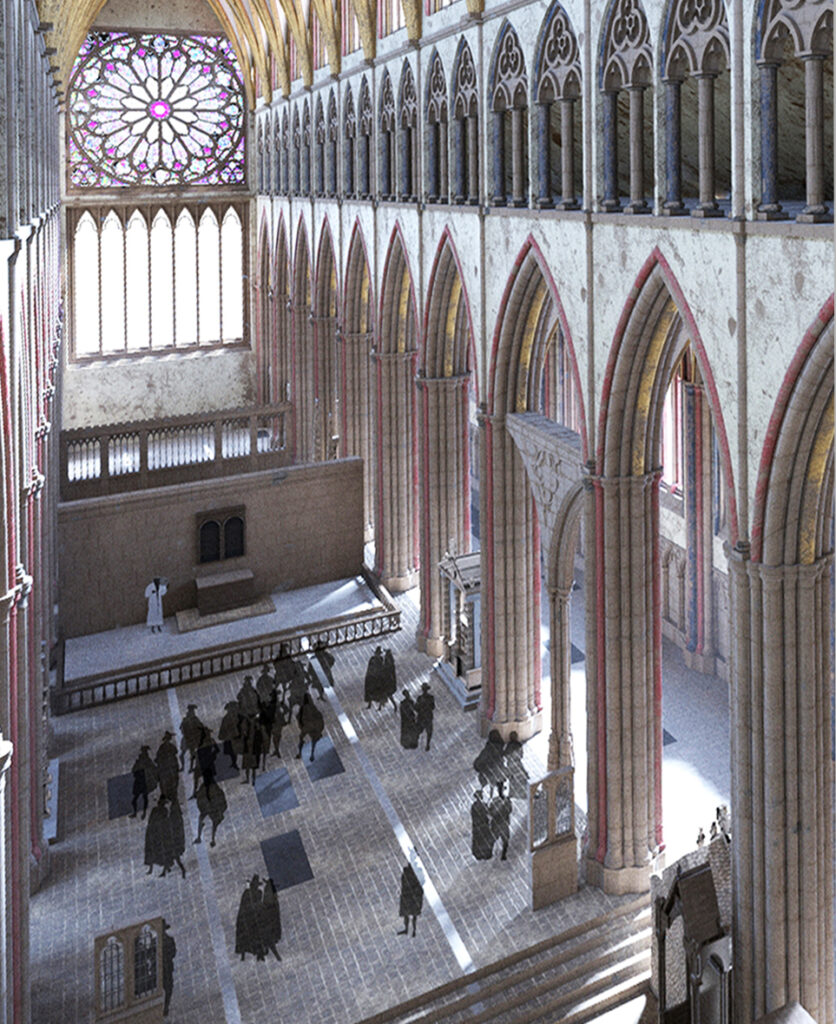

The Virtual Cathedral Project includes a VR version of the Choir area of the Cathedral, go here https://vpcathedral.chass.ncsu.edu/?page_id=2322

Inside this rendering of the Visual Model, one can move about the Choir at will. Still in the works is an enhanced version which will include access to the recordings of the worship services at the center of the Cathedral Project, which will change in sound as the user moves about the space.

With world enough, and time and money, we will complete the VR experience to include the rest of the Cathedral’s interior as well as the Churchyard around the Cathedral.

Adding Human Figures

The observant user of the sites and models clustered under the Virtual Donne umbrella will notice that the visual images on the Paul’s Cross site and the Trinity Chapel site contain human figures to suggest the relative size of spaces and to clarify how people used these spaces for worship. However, fewer of the images on the Cathedral site are populated by human figures.

Some are.

But many, including some of the most important ones, are not.

This is a limitation of our work, the consequence of the need to address more pressing visualization needs at the end of our funding period. It can, of course, be remedied.

Documenting the Models

Another feature of our Visual Models still to be developed is a way to document for each image the sources we drew on in creating a model of a specific building or creating a specific space between buildings. We hoped to create a system which — if one hovered a mouse pointer over a specific image of St Paul’s or any other structure in our models — would link the user directly from an image to the source data for that image and to a discussion of what kind of representation this image creates. We thus hoped to clarify whether any particular model uses highly specific or concrete data or whether it draws on our knowledge of what a building of this age and this function would have generally looked like, thus demonstrating whether this specific image is highly accurate or more or less generic or representational.

All the models on view in this website are based on data gathered from a variety of sources. Some of the buildings draw on specific images; others are more generic, based on visual records of buildings from the 16th and 17th centuries of the same scale, or built for the same use, or As discussed here on this website (https://vpcathedral.chass.ncsu.edu/?page_id=122), part of this data comes from archaeological excavations. The foundations of St Paul’s and of the Paul’s Cross preaching station are still in the ground in London and have been excavated at various points since the Great Fire. For dimensions of width and the specific location of the building itself there is truly hard data, for the stones speak for themselves.

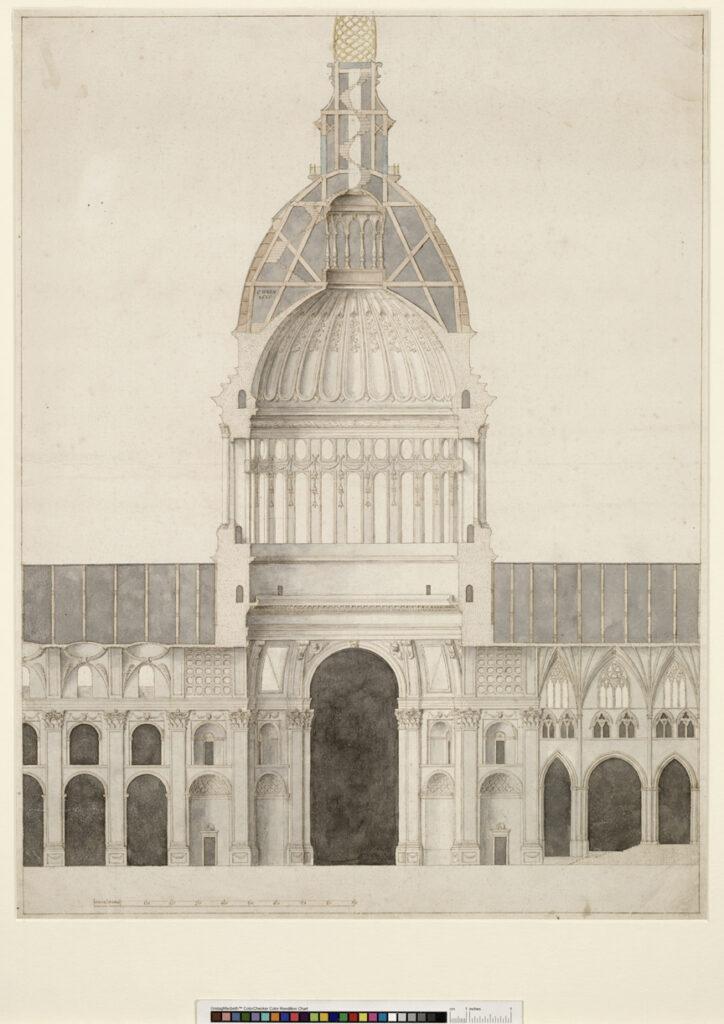

For the height of the building — and of the windows and various levels of wall sections — we can thank Christopher Wren, who, before the Great Fire, created a design for renovating the Cathedral which he embodied in a scale drawing which shows an unfortunate dome to replace what was left of the medieval tower. For our purposes, however, we are grateful to Wren for including a scale drawing of the medieval interior walls.

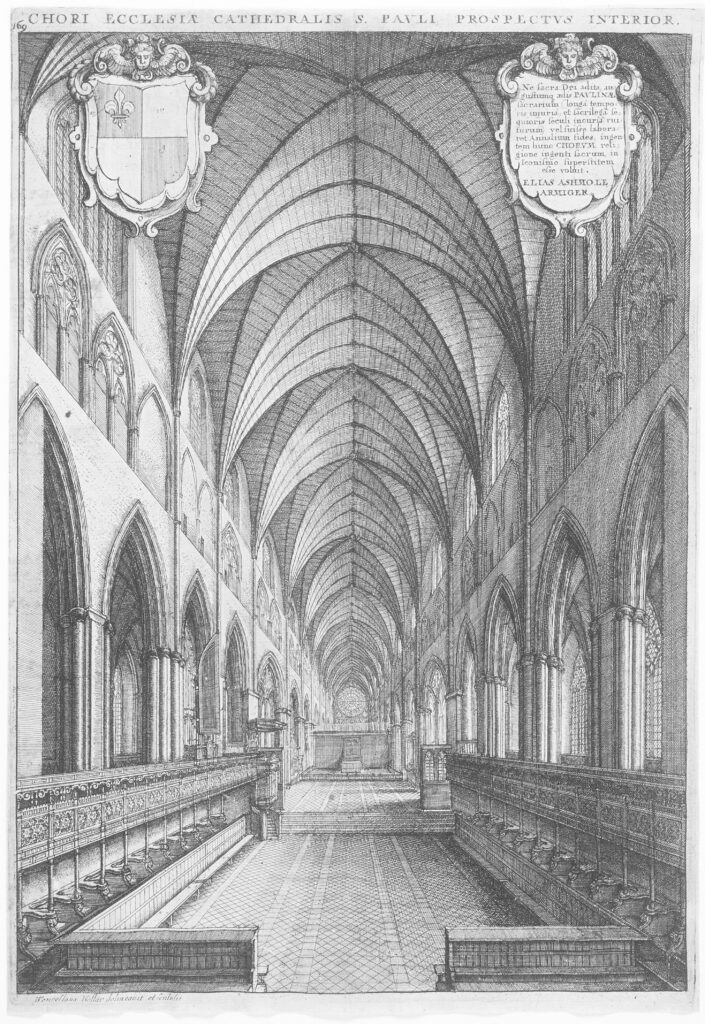

Other data contemporary with the building comes from the visual record, most notably the drawings and engravings of Wenseslaus Hollar for William Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s, published in 1658. As we discuss elsewhere, these images differ in both large ways and small, calling for careful review. For other buildings, we might note a general location and roof style from an image and depend on the historic record to help us fill in the details.

Again, this work still lies in the future. Substituted for it is an extended discussion of kinds of data, how we used it, go here: https://vpcathedral.chass.ncsu.edu/wp-admin/post.php?post=122&action=edit

Polishing the Eagle

For example, we have recently become aware of a document that indicates that a member of the Cathedral’s custodial staff received payment for “polishing the eagle.” What this means is not clear from the document, but it might mean that St Paul’s had a brass lectern with an eagle on it used in the Choir to hold the folio copy of the Bible — in the 1620’s, the Authorized, or King James Bible of 1611 — from which the Lessons appointed by the Prayer Book Lectionary would have been read during services.

Eagle Lecterns. Images courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

These brass lecterns were common in cathedrals and churches in the 16th and 17th centuries; the one pictured above is c. 1500. We considered making the one in our model a lectern like this but opted for a simpler design since we had no specific evidence that St Paul’s lectern was of this design or materials. Future versions of our model may well want to adopt this design so that the custodians of our model may be able to earn extra money by polishing this eagle.

Completing the Choir Stalls

As mentioned elsewhere on this site, we followed Hollar’s depiction of the Choir Stalls, which show the stalls for the Canons stretched around the north and south sides and the west end of the Choir in a single row. Hollar shows a bench running around in front of the stalls, presumably to provide seating for the Cathedral’s Choir.

Future research may find support for a double row of Choir Stalls and/or for the location of kneelers and music stands in front of the singers’ bench, perhaps as shown in this photograph of the 14th century Choir Stalls at Winchester Cathedral.

Documenting the Houses in Paul’s Churchyard

For another, more significant example — well after we had modeled the houses on the South Side of the Cathedral as representationally accurate, our archaeological consultant John Schofield found a survey of the Deanery which gave us more specific information about its size and organization. This survey was made in 1649, after the abolition of the Church of England by the Commonwealth government; the cathedral had been closed, the lands of the Dean and Chapter surveyed, because the Commonwealth government viewed them as assets to be sold.

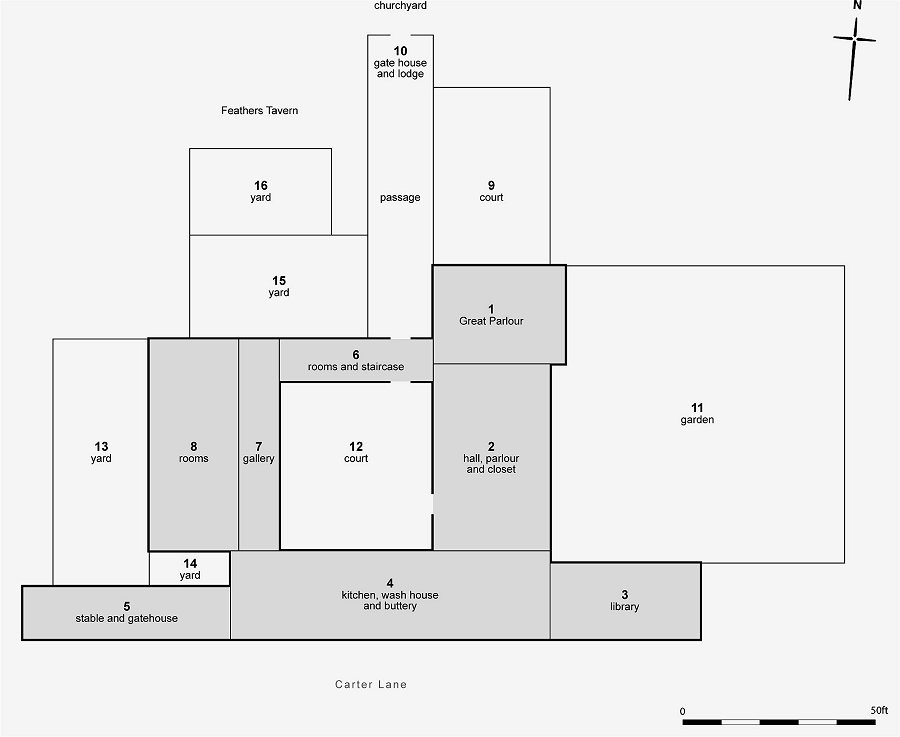

Here is Schofield’s survey:

Fortunately, Schofield made this discovery in time for us to incorporate it into our exterior model, thus:

But we are convinced that the Commonwealth government also surveyed other buildings in the Churchyard owned by the Cathedral, and that their dimensions are also to be found in the Parliamentary Survey in the London Metropolitan Archives. They await those who follow us in working on the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Model.

There are parts of the Visual Model that are based on more substantial data than others. For example, in our Visual Model, the houses on the northeast side of the Churchyard are modeled on the basis of measurements and descriptions contained in surveys of the foundations of these buildings which owners of the property were required to provide to the government of the City of London as a condition of their rebuilding this property. Our models in this area, therefore, combine these specific detail with more generic characteristics one finds in surviving images of these kinds of buildings.

The houses on the south side, except for the Deanery, of course, are shown as houses of the period, based on the property boundaries on Ogilby and Morgan’s post-Fire map of 1676 and therefore may be said to be representationally accurate; that is to say, they are based on surviving images of these types of structures. For more on our modeling principles embodied in these structures, see the discussion elsewhere on this website.

Future work may help us provide more specific details about the houses of the Chancellor, Precentor, Treasurer, and other cathedral dignitaries who lived in this area of the Churchyard. Recently, Roger Bowers, our resident authority on cathedral music, has brought to our attention that the Ledgers of the cathedral’s Chapter survive, also in the London Metropolitan Archives. These ledgers contain, as Bowers puts it, the Chapter’s “office copies of the leases it had made of the properties it owned.” These accounts include detailed descriptions of the porperties inside the Churchyard, as well as accounts of when they were leased out, and to whom.

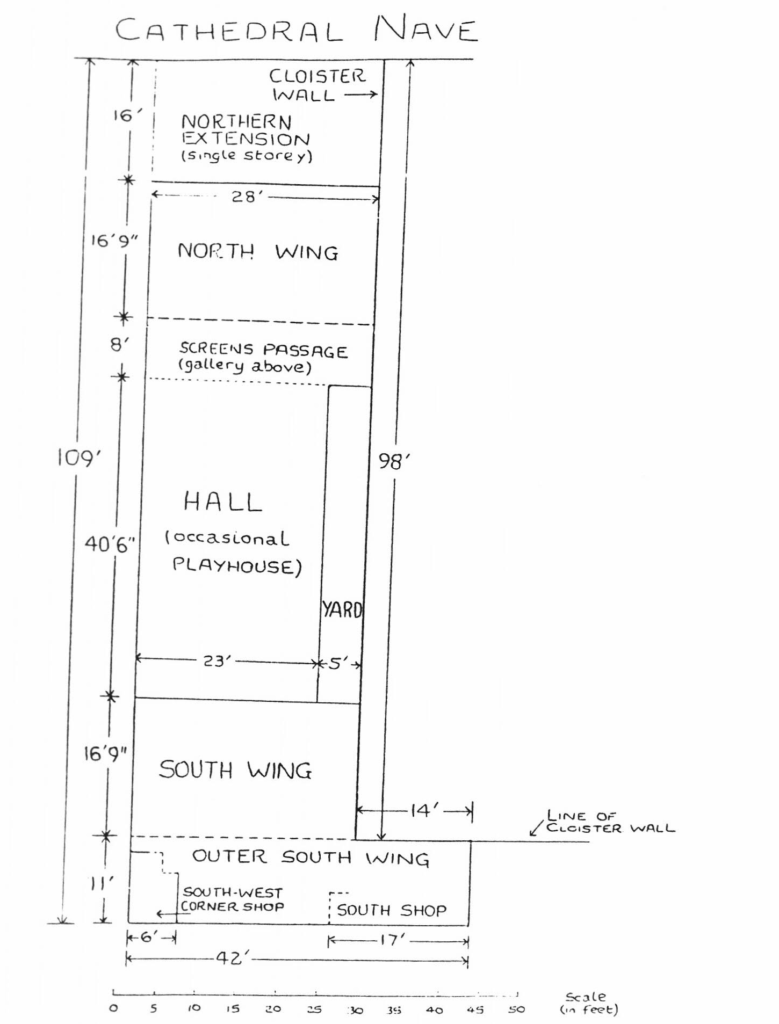

Bowers used these records to create a description of one structure inside the Churchyard, the Almoner’s House, just south of the nave and west of the wall around the Cathedral’s Chapter house. Here is Bowers’ reconstruction of the building based on the evidence contained in the Dean’s Register for Donne’s time as Dean:

Here is our current model of the Almoner’s House, based on surviving images:

Our models are similar, not identical. In this case, as in the case of all the structures, our information came too late in the modeling process for us to take full advantage of it.

As we move the Project closer to a stopping point — so we can write final reports to the NEH, for example — we look forward to what others may uncover that will bring new light, as well as renewed accuracy, to our models.

Smells

One persistent question we have received throughout our work on both the Paul’s Cross Project and the Cathedral Project has to do with the possibility of expanding our modeling beyond sight and sound to others of the five senses — touch, taste, and smell.

The one we get the most questions about is the possibility of adding smell. Given the adeptness of folks today in creating specific smells through artificial means, this expansion could be a real possibility.

The first challenge here would be to reconstruct what specific smells someone attending either a sermon outdoors at Paul’s Cross or worship services inside the Cathedral would be the most likely to encounter. One questioner suggested that the most likely smells one would encounter in Paul’s Churchyard would have been the aromas of horse manure and rotten cabbage, reflecting certain conclusions about the large population of horses that must have been around to facilitate the movement of goods and people and the challenges people faced in the disposal of garbage and sewage.

Such an effort would be supported and informed by the growing number of studies of cityscapes and the conditions and organizations of urban life, especially in London, which was going through a rapid period of population growth in the early modern period. One early learning from this work is that the citizens of early modern London may well have been far more adept in dealing with the material conditions of urban life than we might expect, given our awareness of their lack of garbage trucks and land fills

We look forward to seeing what future recreators of the sights and sounds — AND smells — of early modern London might make available to us.

A Possible Link between Medieval St Paul’s and Wren’s St Paul’s

We know that stones from Medieval St Paul’s were reused in the construction of Wren’s baroque replacement. If you take the guided tour of Wren’s Cathedral, the tour guide will probably point some of these out to you when you are being guided around the basement.

Three sets of facts may provide clues to a further link.

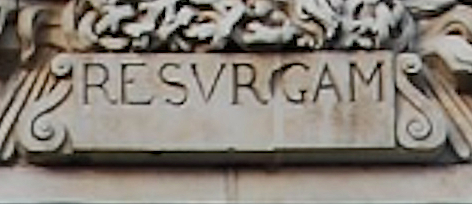

The first set includes the data that John King, Bishop of London (who ordained Donne to the diaconate and priesthood in 1615) died on Good Friday, 30 March 1621, and was buried in the south aisle of St. Paul’s Cathedral, under a plain stone on which was inscribed only the word RESURGAM.

RESURGAM is, of course, Latin for “I shall rise again.”

The second set includes the story that Christopher Wren, when he first began to lay out on the floor of the reconstructed cathedral the shape of his proposed dome, called a workman to bring him a bit of stone. The workman grabbed the first piece that came to hand. Inscribed on it in Latin was the word, RESURGAM.

The third set includes that date that above the door of the South Transept of today’s St Paul’s is a carving (see below) which shows a phoenix rising from the fires of his nest. Below the phoenix is a stone carving which says RESURGAM.

The stone here could be an original part of this carving, perhaps inspired by the stone the workman found, but it does seem to have been broken vertically around the letter “G.”

Using a piece of broken stone does not seem to be something a stonecarver might do if one were carving this stone specifically for this doorway, but just the thing one might include in this carving from the old Cathedral, if this stone is the stone the workman found, and especially if the stone the workman found is the stone carving from Bishop King’s grave marker.

Lots of “if’s” there, I know. But, just saying . . . . .