Se non è vero, è ben trovato (If not true, it is well conceived)[1]Borrowed from the title of Diane Favro’s essay “Digital Immersive Reconstructions of Historical Environments,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (2012), 273.

The Parameters of the Model

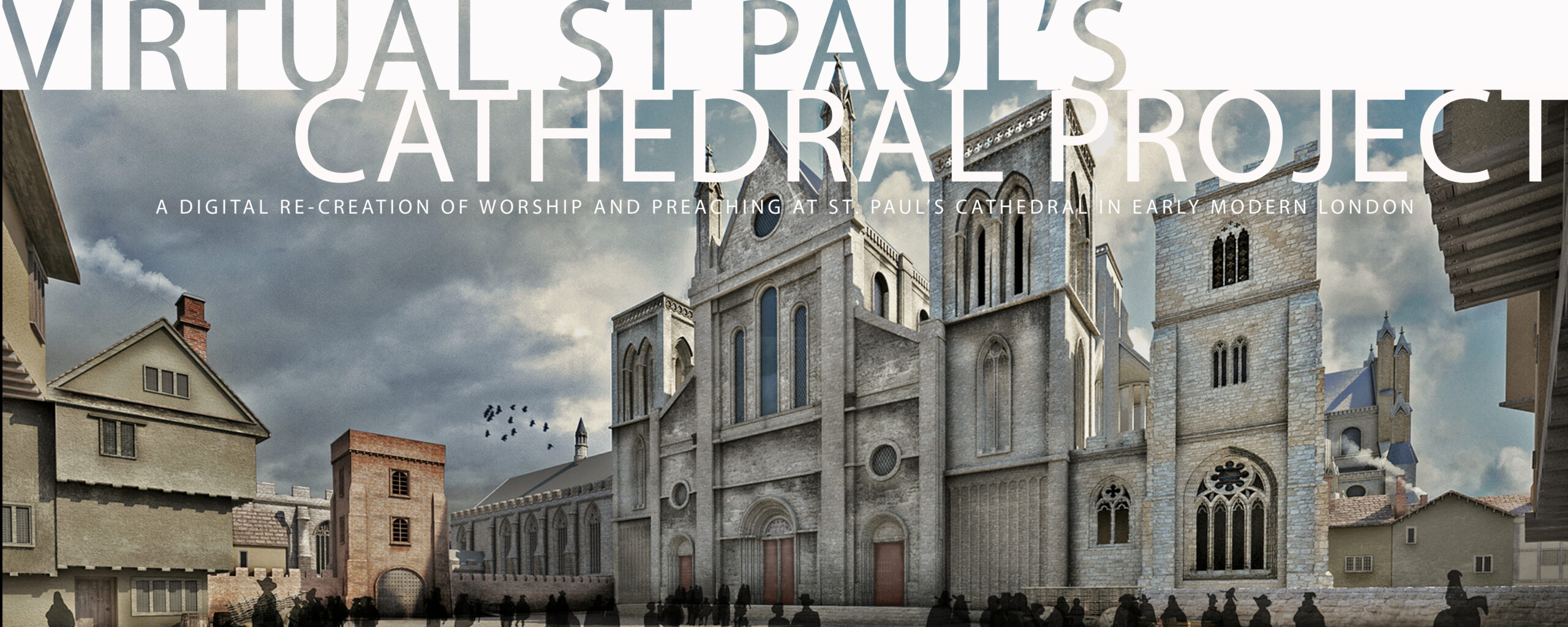

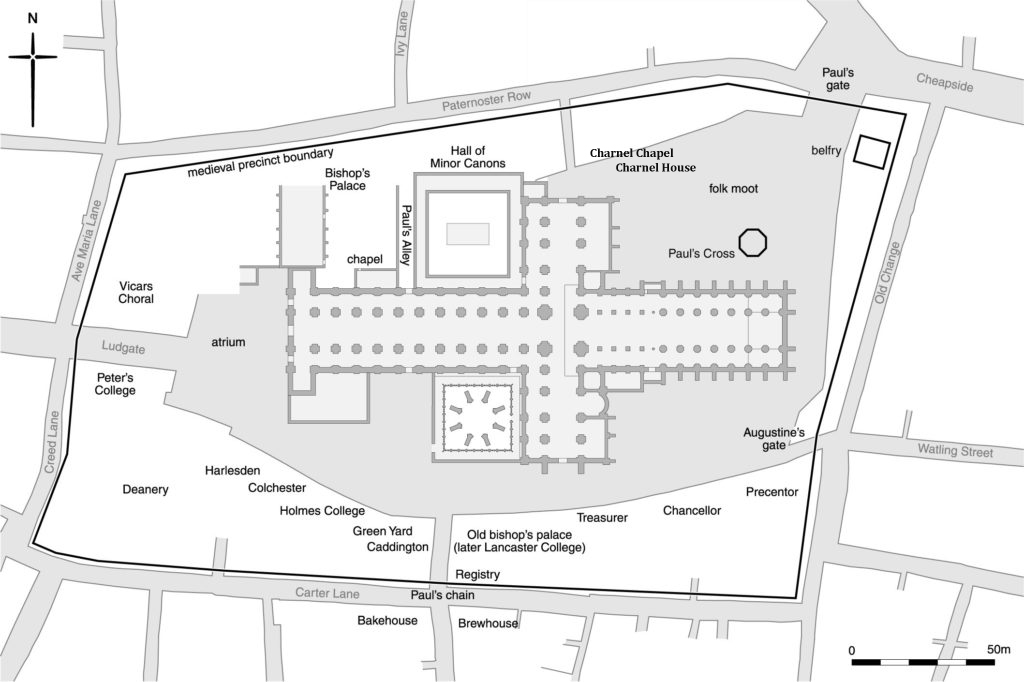

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project, in its Visual Model, depicts St Paul’s Cathedral and the buildings that surrounded it in Paul’s Churchyard, chiefly housing for the Cathedral’s staff and mixed-use houses with retail book shops on the ground floor and living accommodations above.

The model also includes the buildings along the streets that run alongside the wall that separated the Churchyard from the rest of London and faced the streets that surrounded it, specifically Paternoster Row to the north, Old Change Street to the east, and Carter Lane to the south. To the west of the Churchyard, Creed Lane ran north from Carter Lane to Ludgate Street, where its name changed to Ave Maria Lane, before it intersected with Paternoster Row to the north.

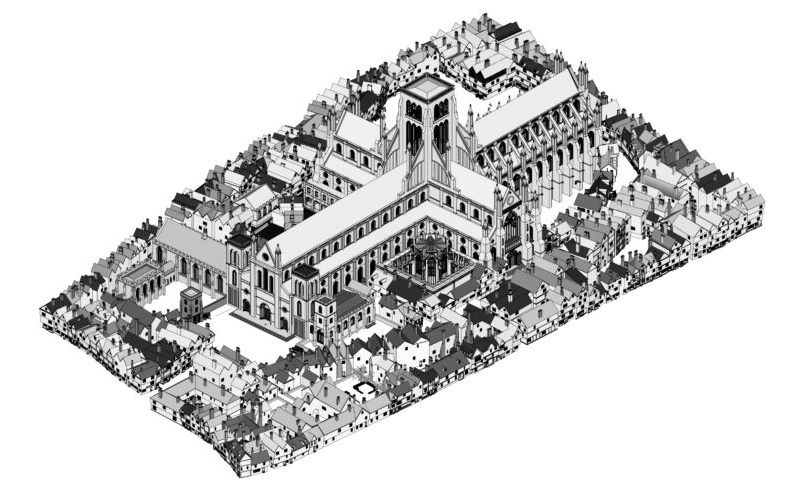

The image to the right, from John Schofield’s St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren, shows the Churchyard around 1500, with its medieval Cloister intact, as well as the sites of the Charnel House and Chapel to the northeast. By 1621 both these structures were gone, leaving room for additional domestic or mixed-use buildings, especially the buildings around the Cross Yard that contained bookshops on the ground floor and housing for the booksellers above.

Our Visual Model seeks to recreate this space, including the buildings within it. Our model is based on a combination of various kinds of evidence. This evidence includes the results of archaeological excavations and early modern records of land surveys that have helped us determine the location and dimensions of the cathedral itself, as well as many of the surrounding buildings. It also includes contemporary visual evidence from engravings, drawings, and paintings.

St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1450. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011)

Kinds of Evidence

Work with this evidence has demonstrated its value in informing us about what was there, and what it looked like, but it has also demonstrated to us the limited and often contradictory nature of this material. While we have sought to create as accurate a model as possible, we have, from time to time, relied both on the design of buildings of various types representative of their kind and, occasionally, on hypothetical recreations of structures — especially of the Cathedral’s West Front — for which we have no direct evidence.

Renderings of portions of the model have also been enriched by signs of aging in the buildings, some of which were already over 400 years old, as well as the effects of weather and the changes in light as the sun moves across the sky.

Much more information about the process of modeling and the sources of evidence we drew on to build it is included in other parts of this section of the website. For now, a word or two about what this model constitutes seems to be in order. This model is not an exercise in time travel, although we have sought to create as realistic and accurate a model as we have been able to. The students who have worked on the Visual Model have, from time to time, implied that they have hidden away an image of a Tardis somewhere on the grounds. But I am sure that there is much we have missed, or misunderstood, or simply got wrong.

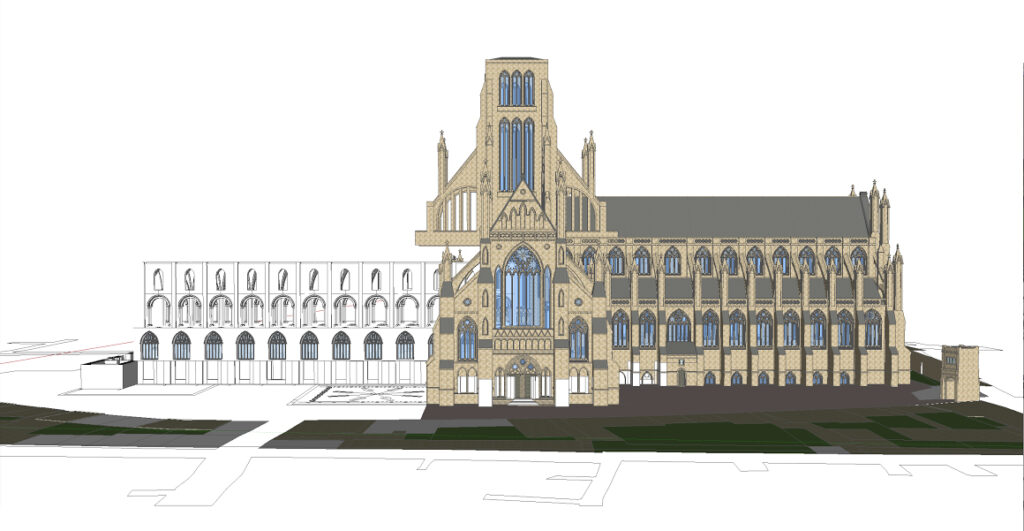

St Paul’s Cathedral, the West Front. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Purpose

We are better off imagining this model as more of an exercise in data visualization than as a depiction of a lost reality. The overall purpose of the visual model is to make it possible for us to explore the physical setting for worship and preaching at St Paul’s Cathedral during John Donne’s tenure as Dean of the Cathedral. While acts of worship and preaching have their generic components, they, nevertheless, are both site- and occasion-specific, grounded in the visual and acoustic characteristics of the spaces in which they were performed, in the scripts for their performance provided by the Book of Common Prayer, and by the social and educational backgrounds of the clergy and their congregations.

The Cathedral Project’s churchyard model is, instead, about using data visualization to organize and synthesize the available evidence into a coherent representation so we can gain a sense of perspective on the spaces in which important events took place, then explore that space for information about what the space might tell us about the significance of what took place there.

The overall goals of the Cathedral Project are, essentially, twofold, to help us grasp the dimensions and relationships of objects and spaces in this time and place, as a context for the events that took place within and outside St Paul’s Cathedral in the early modern era, and to explore, experientially, at least some of those events, as they unfolded in real time. The Cathedral Project is therefore, a tool for imagining more fully the religious life of early modern London, at least from the perspective of the cathedral that stood at its heart.

Stages of the Model

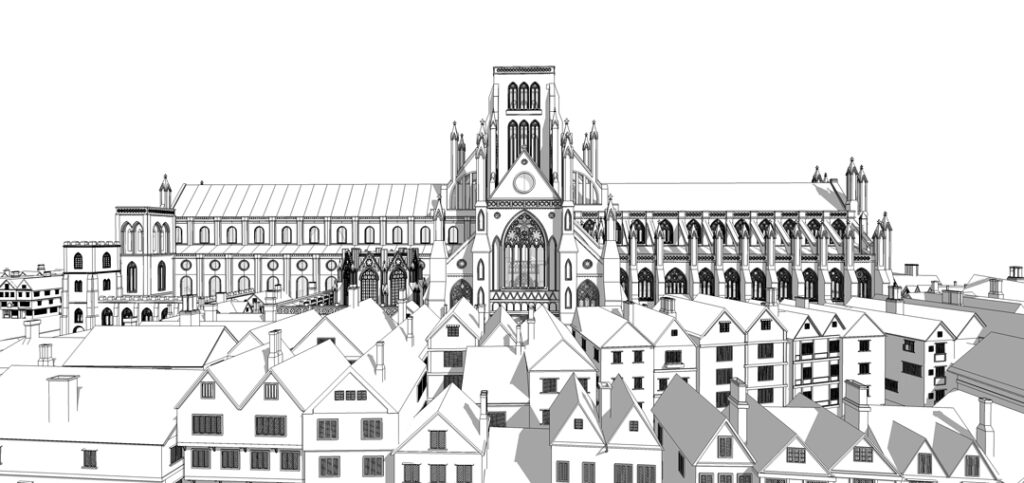

The images below illustrate steps in the process of developing the Visual Model. We of course started with the model built by Joshua Stevens for the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, then began to add the Nave.

Once the Nave of the Cathedral was finished, the next step was the addition of the houses surrounding the Cathedral, in this case, along the south side where the Treasurer, the Chancellor, and the Precentor lived.

Next came the addition of textures, or surfaces, to the structures, and the beginning of decisions about the color of roofs and walls, both of the Cathedral itself and of the houses around it.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the South Side. From the Visual Model, under development by Smith Marks.

We recognized that the color of the Cathedral’s external stone walls would be affected by the color of the light, ranging from tones of grey in cool morning light to tones of yellow in warm afternoon light. Images of the Cathedral throughout this website reflect our effort to illustrate this phenomenon.

References

| ↑1 | Borrowed from the title of Diane Favro’s essay “Digital Immersive Reconstructions of Historical Environments,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (2012), 273. |

|---|