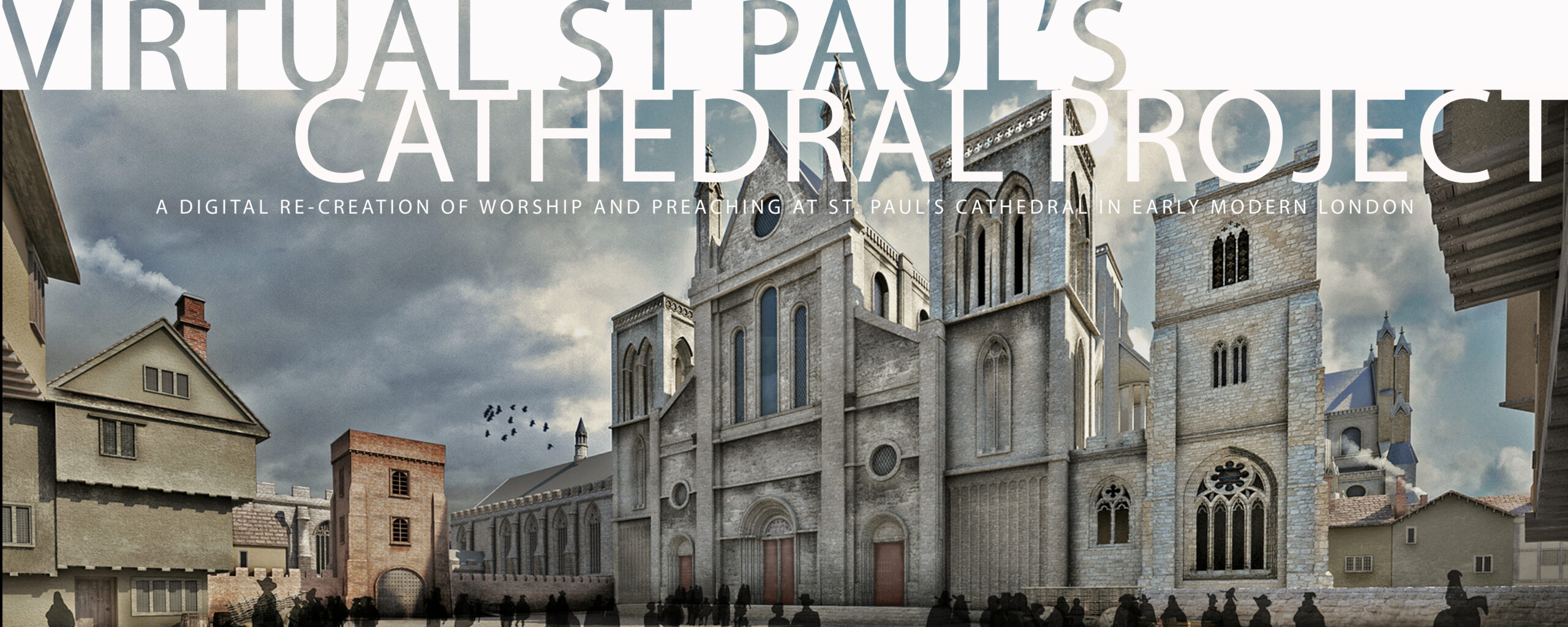

John Donne and the Role of St Paul’s Cathedral in the Life of the Church of England

John Donne was Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral from 1621 to 1631. St Paul’s was (and still is) the cathedral of the Diocese of London, a component part of the Church of England. The position of St Paul’s Cathedral as the cathedral of the Diocese of London, and of Donne as its Dean, are best understood in the context of the organizational structure of the Church of England and of its clergy in the 1620’s. What follows is an attempt to sketch out that structure, to describe the normative expectations that the English had of their state Church, of its structures of authority, its worship services, and of the people’s role in its life.

While there were of course people who disagreed with the Church of England’s ways of doing things, clergy who did not follow their ordination vows to conduct worship services according to the Book of Common Prayer and the Canons of the Church, or who held theological positions different from or even contrary to the understandings of the Christian life as articulated in the official documents of the Church of England, my goal here is to set out what the religious life of most of the English was like.

Especially was this the case in the Cathedral of the Diocese of London, where religious life was under the careful scrutiny of the Bishop of London from his residence in Paul’s Churchyard and of the King himself, from his residence in the Palace of Westminster, two miles away from the Cathedral, as it sat atop Ludgate Hill on London’s western border.

The Church of England

In the 1620’s, the Church of England was the official Christian body in England. With its origins in Henry VIII’s break with Rome in the 1530’s, the Church of England was formalized by the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559), declaring Queen Elizabeth as the Supreme Governor of the Church. When Elizabeth died in 1603, she was succeeded by James VI of Scotland who was crowned James I of England and granted the same title, and role, in the life of the Church of England as Elizabeth had held before him.

James exercised that role early in his reign by presiding, in 1604, over the Hampton Court Conference, a gathering of Bishops of the Church of England and leaders of the Puritan wing of the Church in response to Puritan concerns expressed in the Millenary Petition to King James about their role in the Church.

Among the outcomes of the Hampton Court Conference were two publications that would form the heart of worship and congregational life in the years to come. The first was a revised edition of the Book of Common Prayer (1604), slightly updating the Book of Common Prayer (1559) that had formed the liturgical heart of the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion. The second was an authorized revision of earlier English translations of the Bible, to published in 1611, that would become known as the King James Bible.

Structure of the Church of England

Structure — The post-Reformation Church of England continued the basic internal structure of the medieval English Church, with its division of the country into geographic areas called Provinces, Dioceses, and Parishes.

The Church of England had two Provinces — the Province of Canterbury and the Province of York. Each Province was headed by an Archbishop. or Primate. The Archbishop of York was known as the Primate of England, while the Archbishop of Canterbury was know as the Primate of All England.

Each Province was divided into several Dioceses, each headed by a Bishop. The Archbishops of York and Canterbury were Bishops of their Dioceses as well as Primates of their Provences.

The Province of Canterbury, also known as the Southern Province, contained, in 1600, the Dioceses of Bath and Wells, Bristol, Canterbury, Chichester, Ely, Exeter, Gloucester, Hereford, Lichfield, Lincoln, London, Norwich, Oxford, Peterborough, Rochester, Salisbury, Winchester, and Worcester.

The Archbishop of Canterbury when Donne was ordained (1615) was George Abbot (Ab of Canterbury 1611 – 1633). Abbot was succeed by William Laud, formerly Bp of London (Ab of Canterbury 1633 – 1645).

The Province of York, also known as the Northern Province, contained, in 1600, the Dioceses of Carlisle, Chester, Durham, Sodor and Man, and York.

The Archbishop of York when Donne was ordained was Tobias Matthew (Ab of York 1606 – 1628), who was folliowed by George Montaigne, formerly Bishop of London (Ab of York 1628), by Samuel Harsnett (Ab of York 1629 – 1631), and by Richard Neile (Ab of York 1632 – 1640).

Bishops of London during Donne’s career in the priesthood were John King, who ordained Donne in 1615 (Bp of London 1611 – 1621), George Montaigne (Bp of London 1621 – 1628), and William Laud (Bp of London 1628 – 1633).

Each Diocese was divided into geographic areas called Parishes, each with its Parish Church, served by a priest as rector, often assisted by another priest called the vicar or curate.

In addition to cathedrals and parish churches, the Church of England also had churches, called peculiars, that existed outside the diocesan structure. Chief among them were the Royal Peculiars, which answered directly to the Crown rather than to a diocesan bishop. These included Westminster Abbey, St George’s Chapel, Windsor, and the Chapels Royal at Hampton Court and the Palace at Westminster. Others included the Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy, the Chapels of St Peter ad Vincula and St John the Evangelist in the Tower of London and the Royal Foundation of St Katharine, also near the Tower.

Orders of Ministry

Clergy of the Church of England were ordained by Diocesan Bishops, using the ordination rites (the Ordinal: The form and manner of making and consecrating Bishops, Priests, and Deacons ) provided by the Book of Common Prayer.

In the hierarchy of ministry in the Church of England, Deacons were ordained “to assist the Priest in Divine Service, and specially when he ministereth the holy Communion, and to help him in the distribution thereof; and to read Holy Scriptures and Homilies in the Church; and to instruct the youth in the Catechism; in the absence of the Priest to baptize infants; and to preach, if he be admitted thereto by the Bishop.”

In Donne’s day, the Office of a Deacon was generally a transitional office. In other words, most people going through the ordination process were ordained as Deacons, then ordained as Priests after six or more months. One exception was the poet George Herbert, who was ordained a Deacon in 1626 but was not ordained to the priesthood until 1630. Another exception was Nicholas Ferrar, who was ordained a Deacon in 1626 but — even though he organized and led the religious community at Little Gidding — was never ordained to the Priesthood.

Priests in the Church of England were ordained to the “Office and Work of a Priest in the Church of God,” which consisted of pronouncing forgiveness of sins, preaching “the Word of God, and [ministering] the holy Sacraments in the Congregation, where [they] shalt be lawfully appointed thereunto” as well as to “bring all such as are or shall be committed to [their] charge, unto that agreement in the faith and knowledge of God, and to that ripeness and perfectness of age in Christ, that there be no place left among [them], either for error in religion, or for viciousness in life.”

Bishops in the Church of England were consecrated to “instruct the people committed to [their] charge; and to teach or maintain nothing, as necessary to eternal salvation, but that which [they] shall be persuaded may be concluded and proved by [the Holy Scriptures],” to study “the Holy Scriptures, and call upon God by prayer for the true understanding of the same; so that [they] may be able by them to teach and exhort with wholesome Doctrine, and to withstand and convince the gainsayers,” to “banish and drive away from the Church all erroneous and strange doctrine contrary to God’s Word; and both privately and openly to call upon and encourage others to the same,” to “show [themselves] in all things an example of good works unto others,” to “maintain and set forward . . . quietness, love, and peace among all men; and such as be unquiet, disobedient, and criminous, within [their] Diocese, correct and punish, according to such authority as [they] have,” to “be faithful in Ordaining, sending, or laying hands upon others, and to “shew [themselves] gentle, and be merciful for Christ’s sake to poor and needy people, and to all strangers destitute of help.”

Archbishops were appointd from among the existing members of the House of Bishops and were installed in their new offices without further ordination. The Archbishops of Canterbury and York serve as Bishops of their own Dioceses as well as Archbishops for the Provinces of York and Canterbury. The Archbishop of Canterbury is a higher office than the Archbishop of York, by just a bit, a relationship that is reflected in their titles; the Archbishop of Canterbury is “Primate of All England,”while the Archbishop of York is “Primate of England.”

John Donne’s Career as a Priest in the Church of England

John Donne was ordained Deacon and Priest on the same day, on January 25th, 1615, by John King, Bishop of London, in the Bishop’s Chapel, which was located against the side of St Paul’s, on the north side of the Cathedral.

Being ordained both to the office of Deacon and Priest on the same day was strictly against the Canons of the Church of England, which required that at least six months intervene between ordination to the Diaconate and ordination to the Priesthood. But Donne was being ordained at the request of King James, who had been encouraging Donne for several years to be ordained, and James was, after all, not only King of England but also Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Bishop King was hardly in a position to reject the King’s request.

Clergy appointed rectors of parishes often hired other clergy to serve in their stead, setting up the possibility that a priest might be the rector of more than one congregation.

John Donne, for example, was appointed rector of St John the Baptist parish church in Keyston, in Huntingdonshire, on January 16, 1615, then also became the Reader in Divinity at Lincoln’s Inn in 1616, the same year he also became the rector of St Nicholas parish church in Sevenoaks, in Kent. Without giving up any of these posts, he also became Chaplain to the Viscount Doncaster in 1619 and accompanied him that year on the Viscount’s embassy to Germany.

Donne finally resigned from his post at Keyston in October of 1621, only to become Dean of St Paul’s later that November. He also resigned from his position at Lincoln’s Inn in February of 1622, but was appointed Rector of St Edmund’s Church in Blunham, in Bedfordshire, in April of that year. He also became a vicar at St Dunstan’s in London in March of 1624, a post he held until his death in 1631.

Donne was not totally absent from his parish churches; he preached occasionally and attended Vestry meetings at St Dunstan’s and there are reports of his visiting the rural parishes at least from time to time. He must have had a special connection with his parishioners at St Edmund’s in Blunham, because he gave them a chalice and cover he had had made by a silversmith in London in 1626.

Clergy were appointed by their Bishops, often with input from the local member of the nobility or from the monarch. Clergy salaries were funded by the payment by their parishioners of tithes, or “the tenth part of the increase, yearly arising and renewing from the profits of lands, the stock upon lands, and the personal industry of the inhabitants.”

When Donne resigned from his position at St John the Baptist parish church in Keyston, he sued them for not paying him what he thought he had coming to him in salary.

Clergy in the Church of England had opportunities to hold other posts besides those of parish priest or diocesan bishop. Bishops had staffs of clergy, headed by a senior priest who held the title of Archdeacon. Clergy could serve as chaplains in private chapels in the homes of the nobility. They also staffed the Royal and other Peculiars, the chapels in the Colleges at Oxford and Cambridge Universities and the Inns of Court in London.

Cathedrals had chapters of clergy, called Canons or Prebends. Some of these cathedral clergy were residential, working full time in the cathedral itself. Others had additional posts as rectors of parishes or other church positions; they came to the cathedral for meetings of the Chapter or for special events in the cathedral.

In Donne’s day, St Paul’s had 30 Canons, each one of which had his own seat in the Cathedral’s Choir.

John Donne’s Work Life

In her introduction to Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne (2022), Katherine Rundell gives a profoundly distorted view of Donne’s work life as a priest of the Church of England and Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral. She claims that Donne was a celebrity in his own time; “wherever he was,” Rundell writes, ” people came flocking, often in their thousands, to hear him speak.” Assessing Rundell’s claims is a challenge because the question of crowd size in early modern spaces is difficult to estimate, due to the fact that people are larger today than they were in the Elizabethan age. In addition, it may well be the case that Elizabethan sermon-goers were more comfortable standing closer to each other than we would be today (Notice the close proximity of crowd-members in the image below of Hugh Latimer preaching at the Preaching Place at Whitehall in the Reign of Edward VI.)

The key number that gets reused in discussions of crowd size is John Jewel’s estimate of crowds for Paul’s Cross sermons in the years following the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion as ranging between 5,000 and 6,000 people. Jewel may well have wanted to impress his foreign correspondent about how well England’s second try at a Reformation was going, a likely sign that Jewel was estimating on the high side.

Nevertheless, when we were examining the question of crowd size for the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project

(https://vpcross.chass.ncsu.edu/size-of-the-crowd/) we used a modern-day figure of 4 or so square feet per auditor and found that there was plenty of space in St Paul’s Cross Yard to accommodate a crowd the size of the crowd John Jewel estimates. Interestingly, Benjamin Franklin, in trying to estimate the size of crowds gathering to hear the preacher George Whitfield in Philadelphia in 1739, used a figure of 2 square feet per listener, a figure that would dramatically increase our estimate of the size of crowds attending outdoor sermons.

(chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/becomingamer/ideas/text2/franklinwhitefield.pdf)

That said, however, the only places in London where “thousands” were able to gather to hear Donne preach were Paul’s Cross, inside St Paul’s Cathedral’s churchyard; the Spital, near Bishopsgate; and the Preaching Place at Whitehall Palace. Of Donne’s 160 or so surviving sermons, only one was preached at the Spital and 5 were preached at Paul’s Cross. Donne was a more frequent preacher at Whitehall’s Preaching Place, delivering a series of Lenten sermons there for a number of years. Thus, while some of Donne’s sermons delivered at these sites may not have survived, it is clear that his preaching at outdoor sites where “thousands” might have gathered to hear him were rare occurrences in no way typical of his usual work as a preacher.

Hugh Latimer preaching at the Preaching Place at Whitehall in the Reign of Edward VI. Image courtesy Wikimedia.

Donne’s surviving sermons also include sermons preached at the parish church of St Dunstan’s in the West. I have not been able to determine the actual interior space of Donne’s St Dunstan’s, but I am reliably informed that only a few parish churches in England in this time were large enough to house a congregation in excess of a thousand people (and certainly not “thousands”). Most English Parish churches were much smaller, perhaps closer to the seating capacity of Trinity Chapel at Lincoln’s Inn, which wee have estimated as accommodating around 175 worshipers.

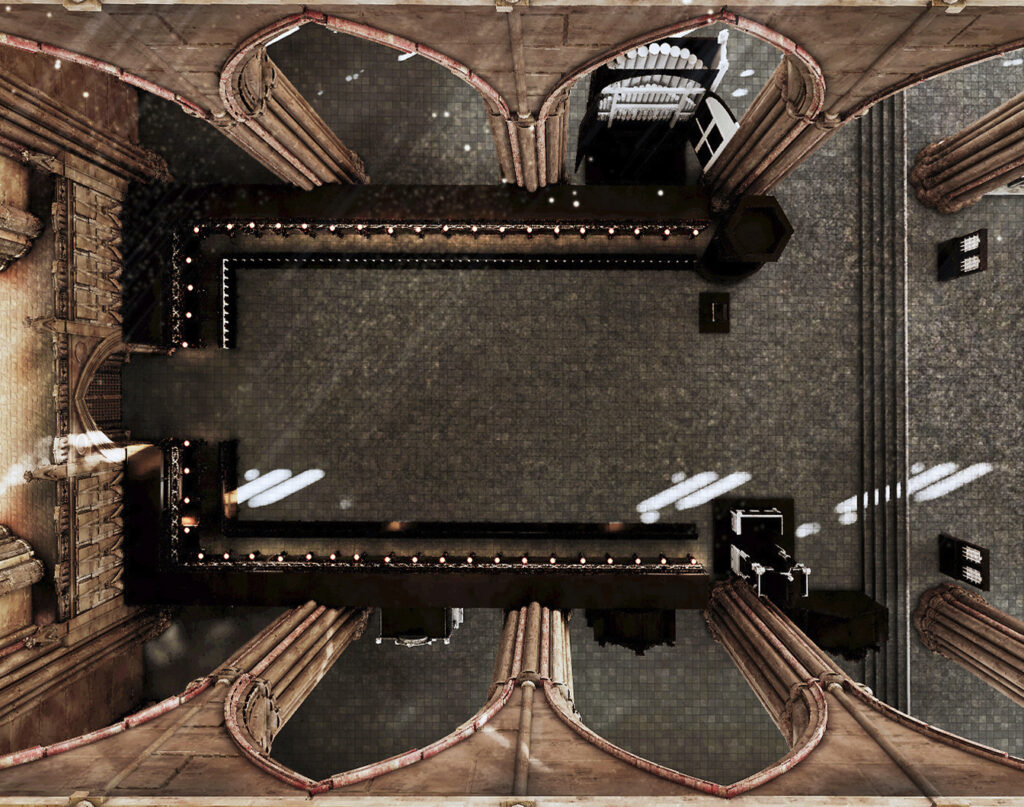

The largest single block of sermons preached by Donne is the collection of at least 57 sermons he preached at St Paul’s Cathedral, in the Choir (since the nave of St Paul’s Cathedral had been given over to secular purposes after the Reformation). The titles of six of these sermons specify that they were preached “in the evening.” But since the practice at the Cathedral was to have the Bishop of London choose the preacher for the morning service and the Dean of the Cathedral choose the preacher for the sermon following Evensong, it is likely that most, if not all, of Donne’s sermons at St Paul’s were preached in the evening.

St Paul’s, the Choir from Above. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

The occasions at which Donne preached at St Paul’s include some of the major feasts of the Christian Year — Christmas, Candlemas, Easter, Whitsunday, and All Saints’ Day — at which one might expect a Cathedral’s Dean to deliver the sermon. As attested to by several of Donne’s surviving sermons for “the day of S. Pauls Conversion,” among Donne’s special responsibilities as Dean was to preach on the feast daay of the Cathedral’s special patron saint.

But other sermons by Donne — including especially his series on the Penitential Psalms — are not connected to specific occasions, suggesting that Donne preached more frequently than on the recurring major festivals. In fact, it is likely to be the case that St Paul’s Cathedral had an organized schedule of preaching dates, with each resident clergy having his special assigned days. Working Donne’s frequent preaching assignments at the Chapel Royal into this schedule must have posed a major challenge for the person assigned for organizing the schedule of services at the Cathedral.

Yet another set of Donne’s surviving sermons are those delivered on special occasions for Donne’s friends, patrons, and social acquaintances. These sermons revelatory of Donne’s social networks — since they were given on the occasions of marriages, funerals, christenings, and churchings — often took place in private chapels or homes, places very unlikely to attract Rundell’s “thousands.” Like Donne’s sermon at the Consecration of Trinity Chapel at Lincoln’s Inn, these sermons address very specific and limited audiences, reminding us that the preaching work of a priest is most often about local concerns and personal relationships, not about topics that would be of interest to large crowds or celebrity clergy.

Convocation

Meetings of Convocation are assemblies of the Bishops and clergy in the Provinces of Canterbury and York. These meetings have been held periodically since the late centuries of the first millenium. The meetings were originally of Bishops, but by 1283 membership had come to include the bishops, deans, archdeacons, and abbots of each province, along with one representative (or proctor) from each cathedral chapter and two proctors elected by the clergy of each diocese.

Members of Convocation met in two Houses, with the House of Bishops meeting separately from the Lower House of deans and other clergy. Meetings of Convocation for the Province of Canterbury took place in Westminster Abbey, after an opening-day ceremony at St Paul’s Cathedral.

John Donne attended meetings of the Convocation of Canterbury while he was Dean of St Paul’s. At the meeting of 1626, he was elected the Prolocutor, or presiding officer of the Lower House. As prolocutor, Donne delivered a Latin oration to a gathering of both Houses of Convocation. [1]For more on Donne’s participation in the Convocation of 1626, as well as the roles of some of Donne’s servants, see Mary Ann Lund’s essay “Donne’s Faithful Servants: Thomas … Continue reading

References

| ↑1 | For more on Donne’s participation in the Convocation of 1626, as well as the roles of some of Donne’s servants, see Mary Ann Lund’s essay “Donne’s Faithful Servants: Thomas Roper and Robert Christmas at St Paul’s Cathedral,” in Old St Paul’s and Culture, forthcoming from Palgrave in 2021. Also, “Donne through Contemporary Eyes: New Light on His Participation in the Convocation of 1626,” The Free Library 1995. |

|---|