Moreover, by this book are priests to administer the sacraments, by this book to church their women, by this book to visit and housle the sick, by this book to bury the dead, by this book to keep their rogation, to say certain psalms and prayers over the corn and grass, certain gospels at crossways, etc. This book is good at all assaies; it is the only book of the world.

— Henry Barrow, A Brief Discoverie, 1590.

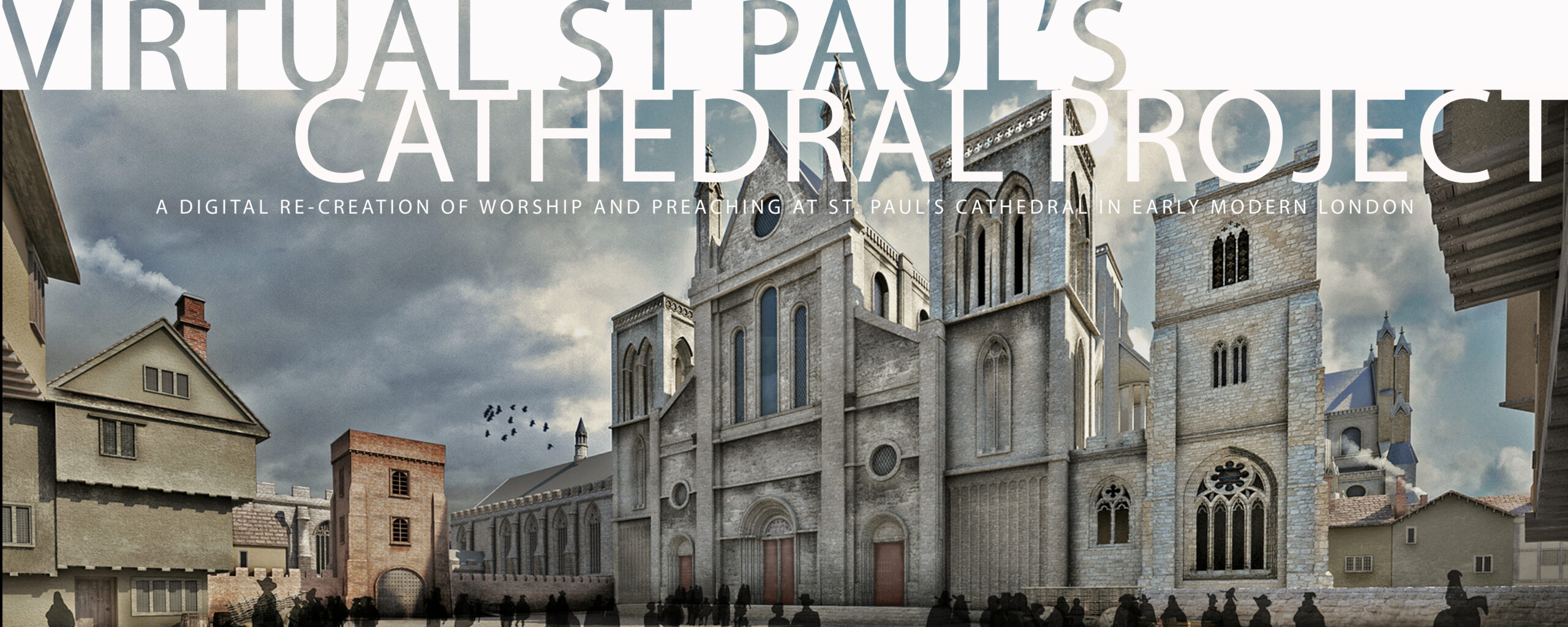

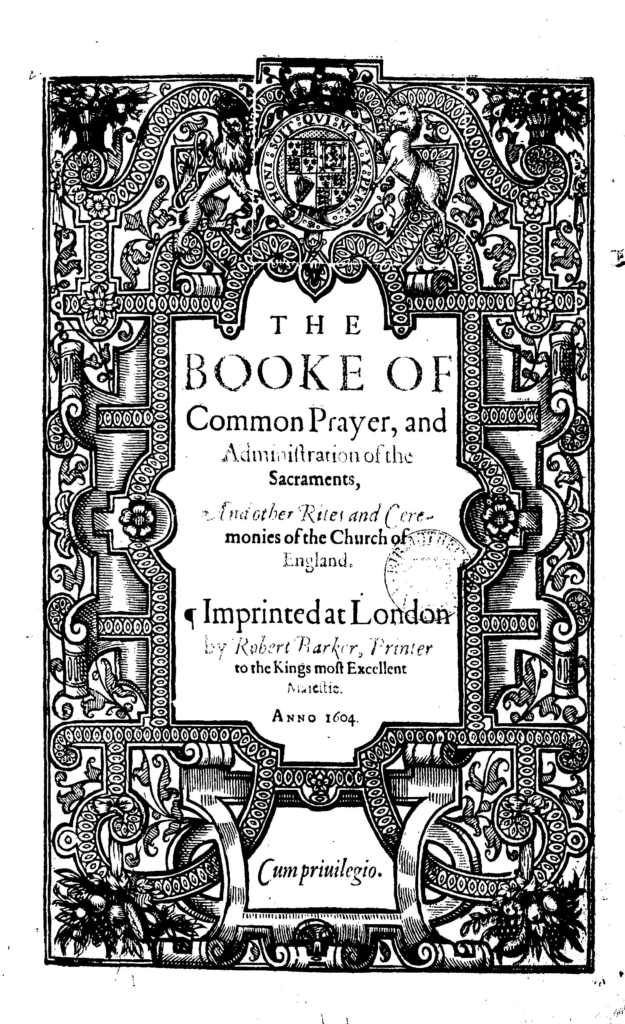

The Puritan Henry Barrow’s description is, of course, right on target, even though his scorn for the Book of Common Prayer is always just below the surface. His true feelings come through more clearly in his summary description of the Prayer Book as “a stinking patcherie devised apocrypha Liturgy.” Barrow’s hostility to the Prayer Book is an indication of the distance the Reformed tradition of Protestantism traveled in the 16th century. After all, Cranmer’s advisors in his compliation of the Book of Common Prayer included Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli, leaders in the early development of the Reformed tradition.

Nevertheless, the Book of Common Prayer was not simply a book written only by Thomas Cranmer, as many historians imply. In fact, as David Griffiths has pointed out, the 1549 Prayer Book was actually complied by Cranmer and a committee of twelve others, including seven bishops and six other dignitaries. Griffiths lists the known members of this committee as “Archbishop Cranmer; Bishops Ridley of Rochester, Holbeach of Lincoln, Thirlby of Westminster, and Goodrich of Ely; Doctors May (Dean of St Paul’s), Hayes (Dean of Exeter, Robertson (afterwards Dean of Furham), and Redman (Master of Trinity College, Cambridge).” [1]David Griffiths, The Bibliography of the Book of Common Prayer: 1549 – 1999 (British Library, 2002), p. 6. As Griffiths puts it, the Church they created was “catholic in liturgy and protestant in using the vernacular, but also ‘established’ in its forms of government.”

Intersections

Worship according to the Book of Common Prayer is in reality a series of acts of coordination scripted by the Prayer Book services which creates for any given day an intersection of that day on the calendar of the secular year with readings from the Bible, the Prayer Book, and the Books of Homilies (or an original sermon, if the priest in charge of the sermon was licensed to preach by his Bishop).

Worship on any particular day takes its contents from the intersection of that day with the Church Year, with that day on the Calendar of Bible Readings and the monthly recital of the Psalter for the Daily Offices of Morning Prayer (also called Matins) and Evening Prayer, on that day and the Calendar of Saints’ days, and on that day with the requirement that the Great Litany be recited on Sundays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and that Holy Communion be celebrted on Sundays, Saints’ Days, and Holy days.

This section of the website is intended to serve as a guide for researchers to create that intersection for themselves for any day in the early modern period, a day when, for example, John Donne or any other priest in the Church of England at the time was preaching, so that one can experience for oneself the Biblical texts, prayers, and other components for the worship events that preceeded and, perhaps, included that sermon.

There is nothing read in our churches but the canonical Scriptures, whereby it cometh to pass that the Psalter is said over once in thirty days, the New Testament four times, and the Old Testament once in the year. . . . . . And, after a certain number of psalms read, which are limited according to the dates of the month, for morning and evening prayer we have two lessons, whereof the first is taken out of the Old Testament, the second out of the New; and of these latter, that in the morning is out of the Gospels, the other in the afternoon out of some one of the Epistles. William Harrison, A Description of England (1577)

The Lectionaries

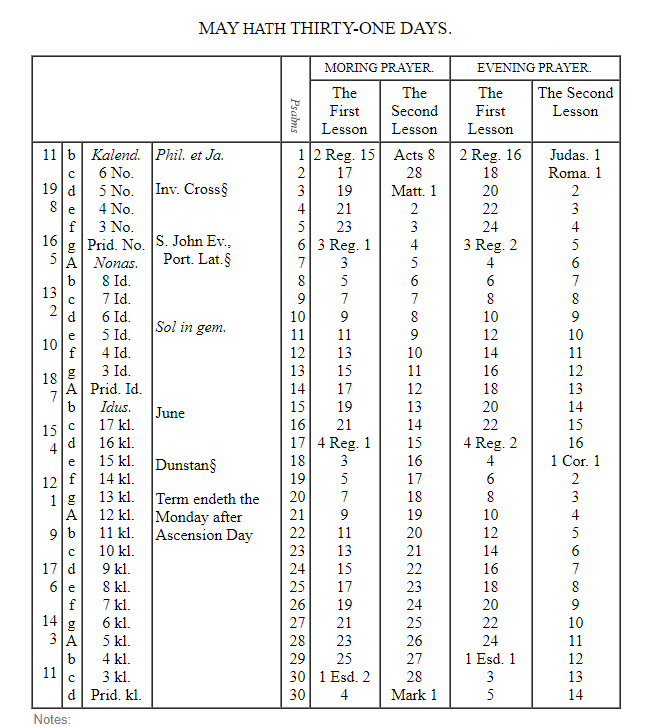

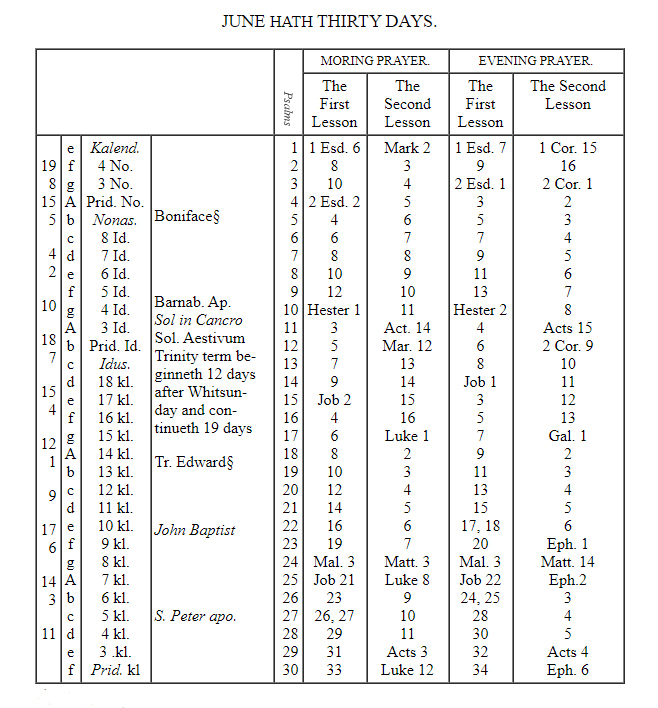

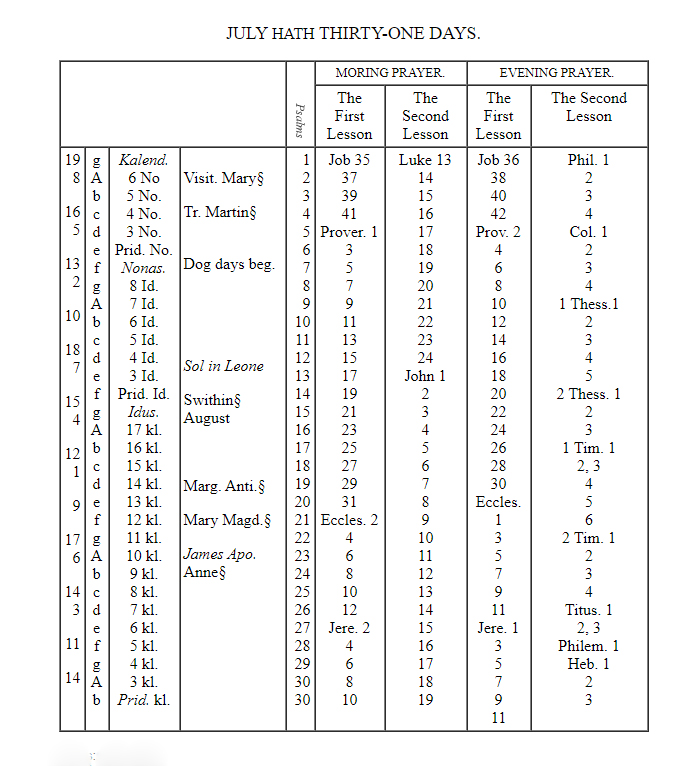

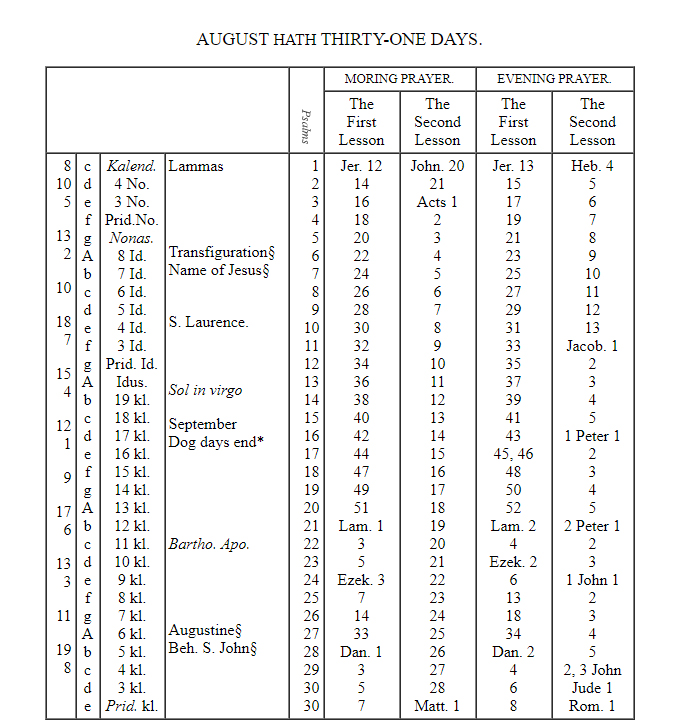

The Book of Common Prayer, from the first edition of 1549, contains three Lectionaries that assign readings from the Bible and the Book of Psalms. The first, the Daily Office Lectionary, assigns a reading from the Old Testament and a reading from the New Testament for each observance of Morning and Evening Prayer for every day of the year. As a result, the follower reads the Old Testament through once a year and the New Testament through three times a year. Along with the Daily Office Lectionary is the “Table for the Order of the Psalms to be Said at Morning and Evening Prayer,” which divides the Psalter into units so that the follower reads the entire Book of Psalms through, in order, once a month.

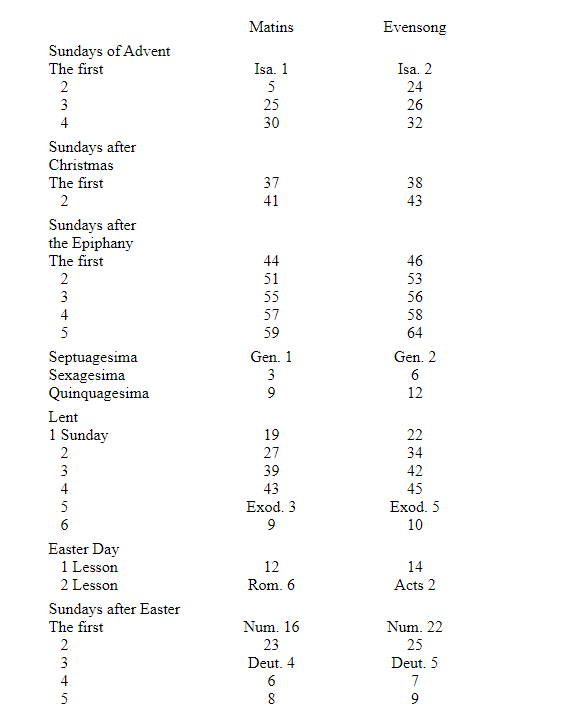

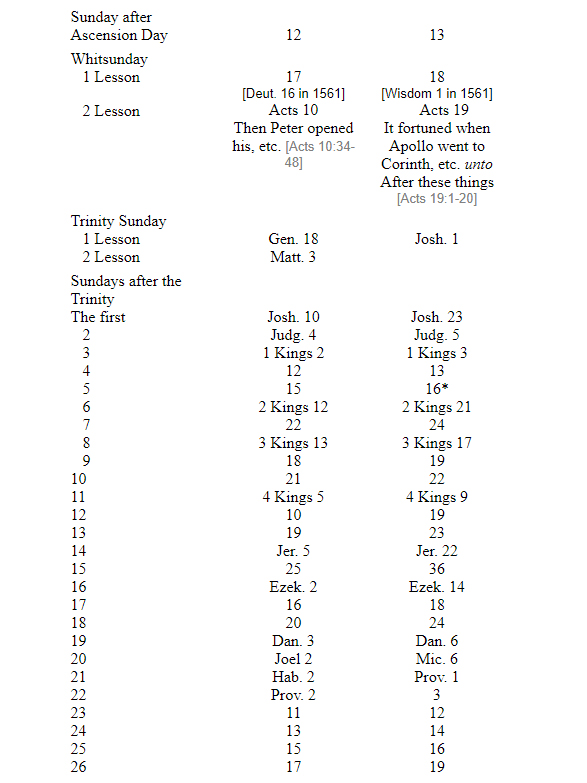

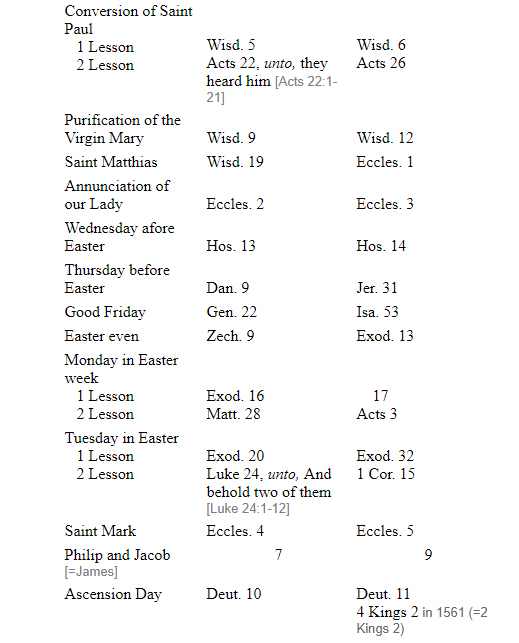

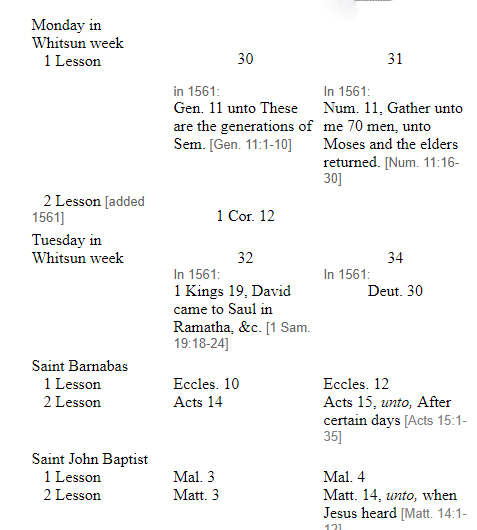

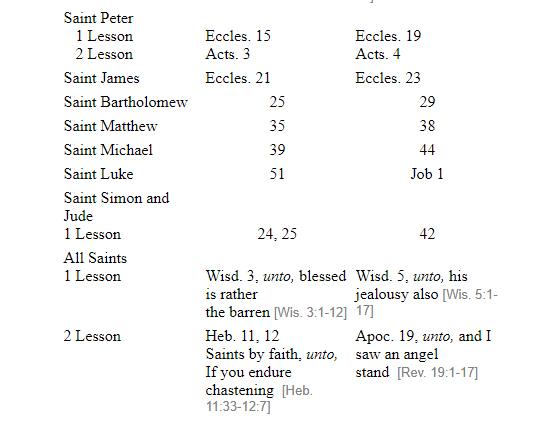

The second Lectionary provides “Proper Lessons to be read for the First Lessons Both at Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer on the Sundays throughout the Year, and for Some, also the Second Lesson.” This Lectionary also provides “Lessons Proper for Holy Days.” When a particular day of the month happens to be a Sunday or Holy Day, the directions for lessons to be read provided by this Lectionary take precedent over the Lessons provided by the basic Daily Office Lectionary.

These two Lectionaries are both found at the beginning of every edition of the Book of Common Prayer in the early modern period, from the very first in 1549 through the Prayer Book of 1604. Both these Lectionaries, plus the directions for reading the Psalter, can all be found at the bottom of this page of the website.

The third Lectionary is called “The Collects, Epistles, and Gospels, to Be Used at the Celebration of the Lord’s Supper and Holy Communion through the Year.” It is found between the text of the Great Litany and the text of the rite of Holy Communion in the Book of Common Prayer. This Lectionary provides Bible readings for teh srvice of holy Communion on that day. The Collects are prayers; there are different ones for each Sunday and Holy Day in the Calendar of the Church Year. The Collect for each Sunday is read at Morning and Evening Prayer on each day of the week that follows each Sunday. An exception is when a Holy Day happens to fall on one of those days, in which case, the Collect for that day would be used instead of the Collect for the preceeeding Sunday.

The Church Year

The Church Year is a term for the liturgical year, which is organized around two central Holy Days, Easter, with its moveable date, and Christmas, whch is always December 25th. Easter Day is always the first Sunday after the full moon on or after Mar. 21. The date of Easter also determines the beginning of the season of Lent on Ash Wednesday and the date of Pentecost on the fiftieth day of the Easter season. The sequence of all the Sundays in the Church Year is based on the date of Easter.

The Church Year, in the early modern period, had six seasons — Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Trinity. Each season has its distinct emphasis, with the Seasons from Advent through Easter using readings from the Gospels that recount the story of Jesus’ life. The Trinity Season, which begins with Trinity Sunday and its affirmation of the doctrine of the Trinity, continues through the Sundays after Trinity. Readings in this Season address the work of the Church, the Christian community, after Jesus’ earthly ministry cumulates in the Ascension of the Risen Christ and God’s bestowal of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost.

Advent

The first season of the Church Year is the Advent Season, which includes the four Sundays before Christmas Day and always begins with the First Sunday of Advent, whihc is always the fourth Sunday before Christmas Day. In early modern Prayer Books, the choices of Collects and Lessons set a tone of preparation, of looking forward, both to the upcoming celebration of Jesus’ Nativity and to Jesus’ promised second coming “in power and great glory.”

Christmas

The Christmas Season begins on Chritmas day, which is also one of the seven principal feasts of the Church Year. The focus of the Christmas Season is of course, Jesus’ birth and its larger significance. The Christmas season lasts for twelve days, from Christmas Day until Jan. 5, the day before the Epiphany. The night called Twelfth Night is the night of the twelfth day of the Christmas Season.

Epiphany

The Epiphany Season always begins with the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6th. The Epiphany Season emphasizes the proclamation of Jesus’ birth to the Gentile world (the Gospel for the Feast of the Epiphany is the story of the coming of the Magi); the Season also includes the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ teaching in the Temple as a youth, and the miracle of Jesus’ turning water into wine at the wedding Feast in Cana. The Epiphany Season in the early modern period could last for 5 or 6 Sundays, depending on the date of Easter.

Pre-Lent

Cranmer’s Prayer Book continued the Medieval tradition of having three weeks prior to the beginning of Lent set aside for preparation for the Lenten Season, which is itself a season of preparation for Easter. The three Sundays in this period have the Latin names Septuagesima (Latin for “seventieth”), Sexagesima (“sixtieth”), and Quinquagesima (“fiftieth”). In the Medieval Calendar the first Sunday in Lent was called Quadragesima (“fortieth”), a reference to the 40 days of Lent, so the three Sundays before Quadragesima were named after the nearest round figures, 70, 60 and 50.

Lent

In early modern Prayer Books, the Lent begins with the Wednesday before the First Sunday in Lent, or, as the Prayer Book puts it, “The first day of Lent.” The traditional name is, of course, “Ash Wednesday,” but Cranmer’s change of name reflects the Church of England’s dropping the imposition of Ashes as part of the English Reformation’s act of separating itself from the Medieval Church. Lent continues, on the model of Jesus’ 40 days of fasting and temptation in the wilderness, for the 40 days plus the Sundays before Easter. Lent culminates with Holy Week, which begins, in the early modern Prayer Book, with the Sunday Next before Easter (traditionally called Palm Sunday). Cranmer’s Calendar retains the reading of Jesus’ Passion from Matthew’s Gospel. Holy Week continues, in Cranmer’s Prayer Book, with assigned Epistle and Gospel readings for celebrations of Holy Communion for each day, the Gospel readings consisting of the accounts of Jesus’ Passion from the Gospels of Mark, Luke, and John. Cranmer drops the traditional names for Maundy Thursday and Holy Saturday, but retains the name Good Friday for that day on the Medieval Calendar.

Easter

Easter is of course the feast of Christ’s resurrection. In England, Easter Day occurs on the first Sunday after the full moon on or after the vernal equinox, thus Easter Day always falls between March 22nd and April 25th. Cranmer’s Prayer Book provides texts, or antiphons, from Romans and I Corinthians to be used instead of Psalm 95 in Morning Prayer.

Easter Day also begins the Season of Easter, which extends, on Cranmer’s Calendar, until the Saturday before Trinity Sunday. It thus includes the Feast of the Ascension and Pentecost, or Whitsunday (the name is a contraction of “White Sunday,” which may be named that because of a tradition of having lots of Baptisms on that day and having people being baptised wear white). Whitsunday of course celebrates the descent of the Holy Spirit, Jesus’ promised comforter, to his followers, with beneficial effects, including the ability to preach the Gospel in all languages. This feature of Whitsunday was, of course, the reason that Cranmer chose Whitsunday in 1549 as the day to implement use of the first Book of Common Prayer.

The Easter Season also includes the occasions for Rogation observations on April 25th and on the Monday to Wednesday of the week of the Celebration of th Feast of the Ascension on Thursday. The name rogation comes from the Latin word rogare, meaning “to ask”; rogation worship includes processions and special petitions to God for protection from God’s judgment and other calamities, including poor harvests. Rogation Days are also associated with the practice of “beating the bounds,” making a formal procession around the boundaries of a parish. The rector or vicar of the parish, together with his churchwardens and other parochial officials would lead a crowd of boys around the parish boundaries. The boys would beat the parish boundary markers with birch or willow boughs. The purpose of beating the bounds was to teach the younger members of the congregation where the boundaries of their parish were, an important task in a time before maps were commonplace. During the procession, clergy would lead the members of the procession in reciting the Great Litany and offer prayer for God’s protection for the parish in the coming year.

Trinity

The Trinity Season begins with Trinity Sunday and extends Sunday by Sunday after Trinity Sunday until the end of the Church Year on the Saturday before the First Sunday in Advent, in late November or early December. The Season of Trinity invites congregations to emphasize the role of the Church in the world, as the Body of Christ on earth, as the people called to continue Jesus’ redemptive work in the world, and as today’s link between the Church of the New Testament, the Church of the future, and the Church ot the world to come.

DAILY WORSHIP

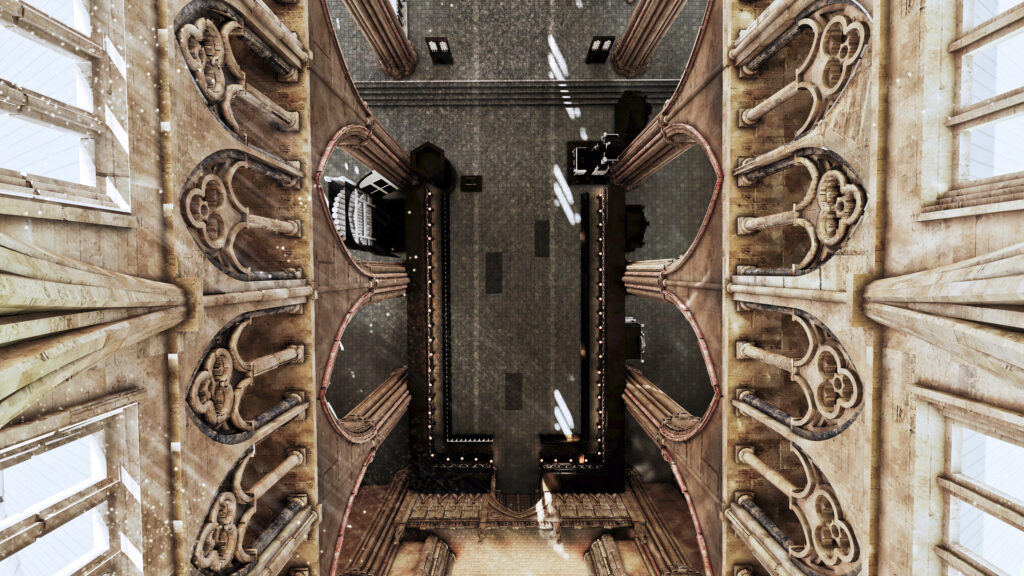

Daily worship in the early modern Church of England consisted of the Daily Offices of Morning Prayer (or Matins) and Evening Prayer (or Evensong), created by Thomas Cranmer for the first Book of Common Prayer of 1549 and continued with only minor changes into the present day. In doing so, Cranmer chose to continue the Benedictine tradition — a part of Christian practice in England since the days of St Augustine, of Canterbury — of structuring the day around regularly scheduled occasions for corporate reading of scripture and intercessory prayer.

Use of Daily Offices as formal occasions for communities of the faithful to join in structured reading and hearing of the Bible remind us that the Church of England established by the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) was at heart corporate and liturgical. Twice daily, members of the faithful across the nation gathered for common prayer, united by their participation in listening and speaking, and in responding through confession, through prayer, and through praise.

John Donne, in his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, recognizes this fundamentally corporate character of the “Christian Church” in which God has “planted” him when he acknowledges God’s presence in the corporate gathering of the worshipping community but not necessarily in his bedroom in the Deanery. “God’s “breath,” writes Donne, “in the Congregation, thy Word in the Church, breathes communion and consolation here [in this life], and consummation hereafter.” Donne’s language assumes the collective — the challenge he believes he faces, at the beginning of the Devotions, lies in his separation from that community, hence from God in that community. Donne situates himself, as a result of his illness, as apart from that congregation, a separation that he believes has serious consequences for him. “I lye here,” Donne writes, “I lye here and say, Blessed are they, that dwell in thy house, but I cannot say, I will come into thy House.” And, again, “Where I lie, I could heare the Psalme, and did joine with the Congregation in it, but I could not heare the Sermon.” And, again, “My friends [are at] their prayers in the Congregation,” but “I [am] in a solitude,” and “woe unto me,” he says, “if I bee alone.”

Donne and other clergy in the Church of England committed themselves at their ordinations to reading the Daily Offices as public services in cathedrals and in their parish churches. Walton’s biography of George Herbert records his compliance with this discipline and documents its practice on a daily rather than on a Sunday-only model:

Mr. Herbert’s own practice . . . was to appear constantly with his wife and three nieces—the daughters of a deceased sister—and his whole family, twice every day at the Church-prayers, in the Chapel, which does almost join to his Parsonage-house. And for the time of his appearing, it was strictly at the canonical hours of ten and four: and then and there he lifted up pure and charitable hands to God in the midst of the congregation.

And he would joy to have spent that time in that place, where the honour of his Master Jesus dwelleth; and there, by that inward devotion which he testified constantly by an humble behaviour and visible adoration, be, like Joshua, brought not only his own household thus to serve the Lord; but brought most of his parishioners, and many gentlemen in the neighbourhood, constantly to make a part of his congregation twice a day: and some of the meaner sort of his parish did so love and reverence Mr. Herbert, that they would let their plough rest when Mr. Herbert’s Saint’s-bell rung to prayers, that they might also offer their devotions to God with him; and would then return back to their plough.

And his most holy life was such, that it begot such reverence to God, and to him, that they thought themselves the happier, when they carried Mr. Herbert’s blessing back with them to their labour. Thus powerful was his reason and example to persuade others to a practical piety and devotion.

Cranmer developed these two services to enable the nation as a whole to join (either literally or metaphorically, since on some days the cathedrals and some parishes did the reading, listening, and responding for others) in this cycle of scripture readings and prayer. He developed them out of the daily corporate prayer life of monastic communities in the medieval church. By doing so, Cranmer consolidated the Hours of the monastic day, which featured 8 offices of prayer and scripture reading for which members of the communities gathered in their chapels.

They were, as follows:

- Matins (during the night, at about 2 a.m.)

- Lauds or Dawn Prayer (at dawn, about 5 a.m., but earlier in summer, later in winter)

- Prime or Early Morning Prayer (First Hour = approximately 6 a.m.)

- Terce or Mid-Morning Prayer (Third Hour = approximately 9 a.m.)

- Sext or Midday Prayer (Sixth Hour = approximately 12 noon)

- None or Mid-Afternoon Prayer (Ninth Hour = approximately 3 p.m.)

- Vespers or Evening Prayer (“at the lighting of the lamps”, about 6 p.m.)

- Compline or Night Prayer (before retiring, about 7 p.m.)

While the early years of the English Reformation saw the dissolution of monastic communities, Cranmer retained the monastic practice of structuring the day through daily offices at specific fixed times of day set aside for prayer and the reading of scripture as his model for daily worship of the whole nation, not just those living in formal community. He in effect consolidated the first four monastic offices into Morning Prayer or Matins and the other four into Evening Prayer (or Evensong, for places “where they do sing,” as the Prayer Book puts it), with the goal of making this practice of structuring the day more amenable to the realities of daily living.

Cranmer also set out, as he puts it in the Preface to the BCP of 1549, to emulate the “ancient fathers,” who

so ordered the matter, that all the whole Bible (or the greatest part thereof) should be read over once in the year, intending thereby, that the Clergy, and especially such as were Ministers of the congregation, should (by often reading, and meditation of God’s word) be stirred up to godliness themselves, and be more able to exhort others by wholesome doctrine, and to confute them that were adversaries to the truth. And further, that the people (by daily hearing of holy Scripture read in the Church) should continually profit more and more in the knowledge of God, and be the more inflamed with the love of his true religion.

Noting that this “godly and decent order” has been “so altered, broken, and neglected” that the process of reading Books of the Bible would be started, then interrupted, and often never completed, Cranmer says he offers in the Lectionary of the Daily Offices a Kalendar which is “plain and easy to be understood, wherein (so much as may be) the reading of holy Scripture is so set forth, that all things shall be done in order, without breaking one piece thereof from another.”

“There must be some rules,” Cranmer says, “therefore certain rules are here set forth, which, as they be few in number; so they be plain and easy to be understood. So that here you have an order for prayer (as touching the reading of the holy Scripture), much agreeable to the mind and purpose of the old fathers, and a great deal more profitable and commodious, than that which of late was used.”

His Lectionary “ordained nothing to be read, but the very pure word of God, the holy Scriptures, or that which is evidently grounded upon the same; and that in such a language and order as is most easy and plain for the understanding, both of the readers and hearers. It is also more commodious, both for the shortness thereof, and for the plainness of the order, and for that the rules be few and easy. Furthermore, by this order the curates shall need none other books for their public service, but this book and the Bible: by the means whereof, the people shall not be at so great charge for books, as in time past they have been.”

Cranmer also claims, “where heretofore, there hath been great diversity in saying and singing in churches within this realm: some following Salisbury use, some Hereford use, some the use of Bangor, some of York, and some of Lincoln: now from henceforth, all the whole realm shall have but one use.”

Cranmer’s Prayer Book seeks to overcome the passivity of the Medieval congregation by creating interchanges between the Officiant and the congregation at numerous points through all the Prayer book sservices, also by having numerous occasions in which the Officiant and the congregation join in on group affirmations, such as the Apostles Creed at Morning and Evening Prayer and the Nicene Creed at Holy Communion, also Confessions of Sin and corporate recitations of the Lord’s Prayer.

Given that a significant percentage of the congregation in churches across England were unable to read — a point that William Harrison mentions in his Description of England — the ways in which the interactive aspects of the Book of Common Prayer were implemented, so that congregations could join in “one voice” in address to God, are worthy of further investigation. Some historians believe that clergy solved this problem by speaking the congregation’s parts, line by line, with the congregation repeating each line after the officiating priest.

The rubrics of the Prayer Book suggest, however, that a number of strategies were employed. In addition, congregations surely memorized frequently-used prayers– such as the Lord’s Prayer, repeated several times in the course of a day’s worship — and regularly-repeated formularies — such as the Creeds or the Confessions. In addition, there is a kind of corporate memory, enabled by a mix of parishioners with and without Prayer Books; those with Prayer Books read from them, while other members of the congregation used the readers’ words as prompts for their memories, so they could join into the repetition.

The Directions for Readings

To reconstruct the Office of Morning or Evening Prayer for any day in the calendar year requires several steps. In carrying them out, one needs to remember that the calendar in use in England in the Early Modern Period was the Julian, not the Gregorian, Calendar. To find the date on the Julian Calendar for any day in the Gregorian Calendar, go to this site’s conversion program.

The first step is to identify the portions of the Psalter to be read at Morning and Evening Prayer.

The Psalms

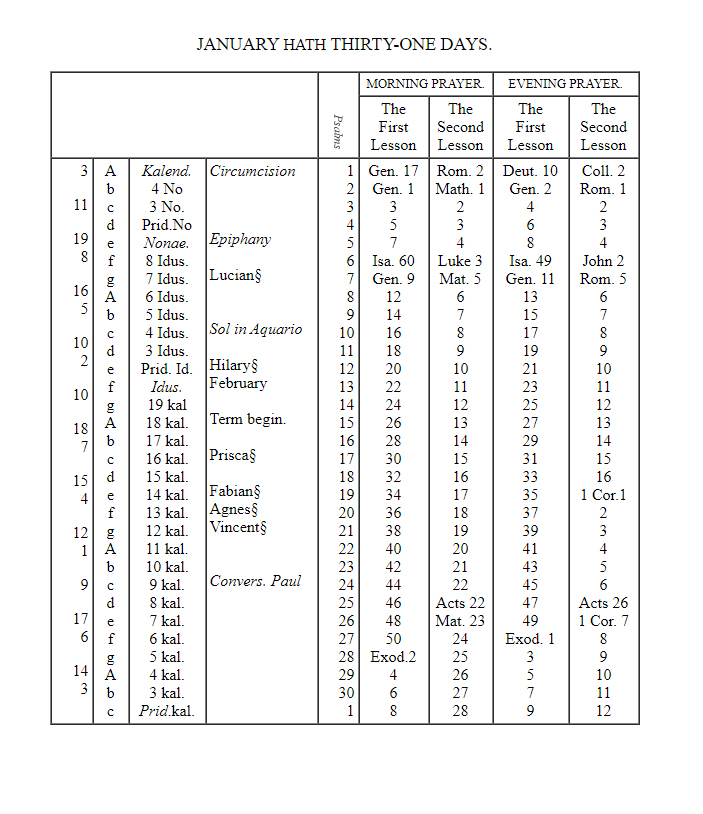

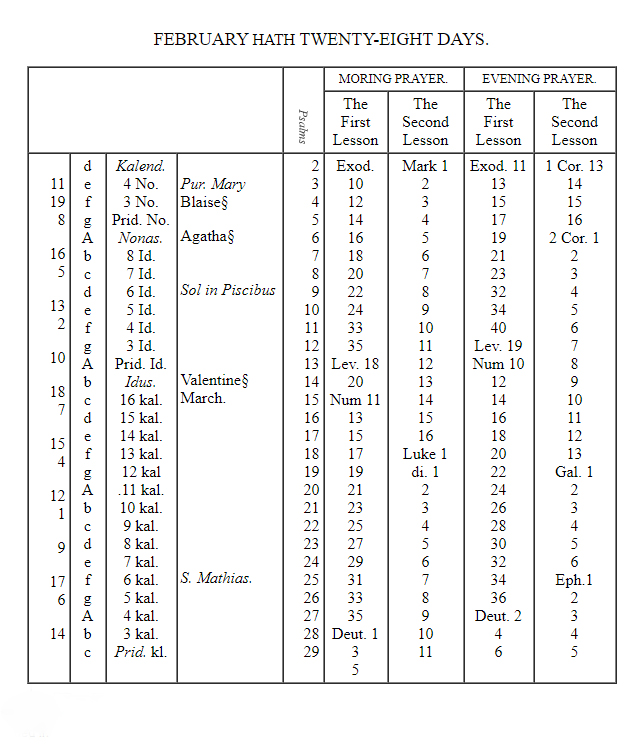

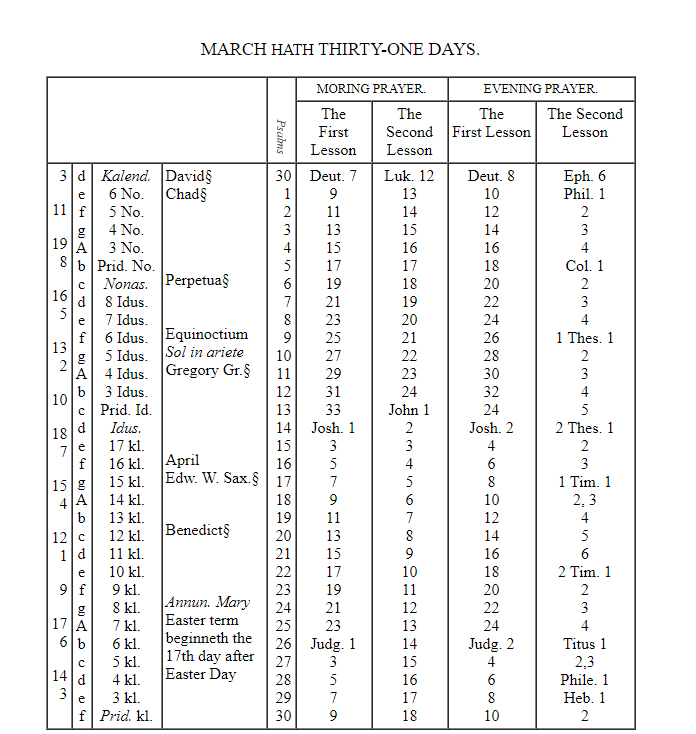

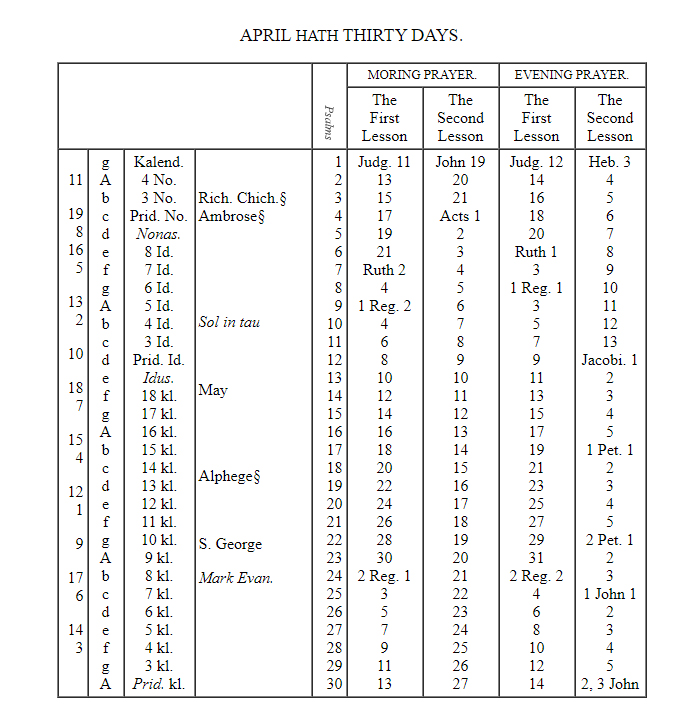

Cranmer’s directions for reading the Psalter so that the Book of Psalms is read straight through breaks the Psalms down according to the table below. For months with 30 days, the first day of the month starts the process with Day One’s readings. Exceptions are months with fewer or more than 30 days. For February, the Order of the Psalter starts with Day 2 and ends with Day 29. For months with 31 days, the month starts with Day 1 and repeats the readings for Day 30 on the 31st day of the month.

EXPRESSYNG THE ORDRE OF THE PSALMES AND LESSONS, TO BEE SAID AT THE MORNING AND EVENING PRAYER THROUGHOUT THE YERE, EXCEPTE CERTAIN PROPRE FEASTES, AS THE RULES FOLOWYNG MORE PLAYNELY DECLARE.

THE ORDER HOW THE PSALTER IS APPOYNTED TO BE READDE.

THE Psalter shalbe readde through, ones euery moneth, and because that some Monethes bee longer then some other be; It is thought good, to make them even by this meanes.

To every moneth shalbe appointed (as concerning this purpose) just xxx dayes.

And because January and Marche hathe one daye above the sayed nomber, and February, which is placed betwene them bothe, hath onely xxviii dayes, February shall borow of either of the monethes (of January and Marche) one day, and so the Psalter, which shalbe redde in February, must begin the last daie of January, and ende the first daie of Marche.

And where as May, July, August, October and December, hath xxxi dayes a pece, it is ordred that the same Psalmes shalbe redde the haste day of the sayed Monethes, which were redde the daye before, so that the Psalter may beginne againe the first daie of the next Monethe ensuyng.

Now to knowe what Psalmes shalbe redde every daie, looke in the Kalender, the nomber that is appointed for the Psalmes, and then fynde thesame nomber in this Table, and upon that nomber shall you see, what Psalmes shalbe sayde at Morning and Evening prayer.

And where the cxix Psalme, is devided into xxii porcions, and is overlong to be redde at one time: it is so ordred, that, at one time, shal not be readde above foure or fyve of the sayd porcions, as you shall perceive to be noted in this Table folowyng.

And here is also to be noted, that in this Table, and in all other partes of the service, where any Psalmes are appoyncted, the nombre is expressed after the greate Englyshe Bible, whiche from the ix Psalme, unto the cxlviii Psalme (folowing the devision of the Hebrues) doth vary in nombres from the common Latine translacion.

THE TABLE

FOR THE ORDER OF THE PSALMES, TO BE SAIED AT

MORNING AND EVENING PRAIER.

| [Day of the month] | ¶ Morning Praier | ¶ Evening Praier |

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 | 1,2,3,4,5 9,10,11 15, 16, 17 19, 20, 21 24, 25, 26 30,31 35, 36 38,39,40 44,45,46 50, 51, 52 56, 57, 58 62, 63, 64 68 71, 72 75, 76, 77 79, 80, 81 86, 87, 88 90, 91, 92 96, 97 102, 103 105 107 110, 111, 112, 113 116, 117, 118 119, verses 33 – 72 119, verses 105 – 144 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125 132, 133, 134, 135 139, 140, 141 144, 145, 146 | 6, 7, 8 12,13,14 18 22, 23 27, 28, 29 32, 33, 34 37 41, 42, 43 47, 48, 49 53, 54, 55 59, 60, 61 65, 66, 67 69, 70 73, 74 78 82, 83, 84, 85 89 93, 94 98, 99, 100, 101 104 106 108, 109 114, 115 119, verses 1-32 119, verses 73 – 104 119, verses 145 – 176 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131 136, 137, 138 142, 143 147, 148, 149, 150 |

On Major Feasts of the Church Year, the following Psalms were substituted from the ones appointed on the above table, to wit:

Proper Psalms on Certain Days

| Matins | Evensong | |

| Christmas Day. Psalm | 19 45 85 | 89 110 132 |

| Easter Day | 2 57 111 | 113 114 118 |

| Ascension Day | 8 15 21 | 24 68 108 |

| Whitsunday | 45 67 | 104 145 |

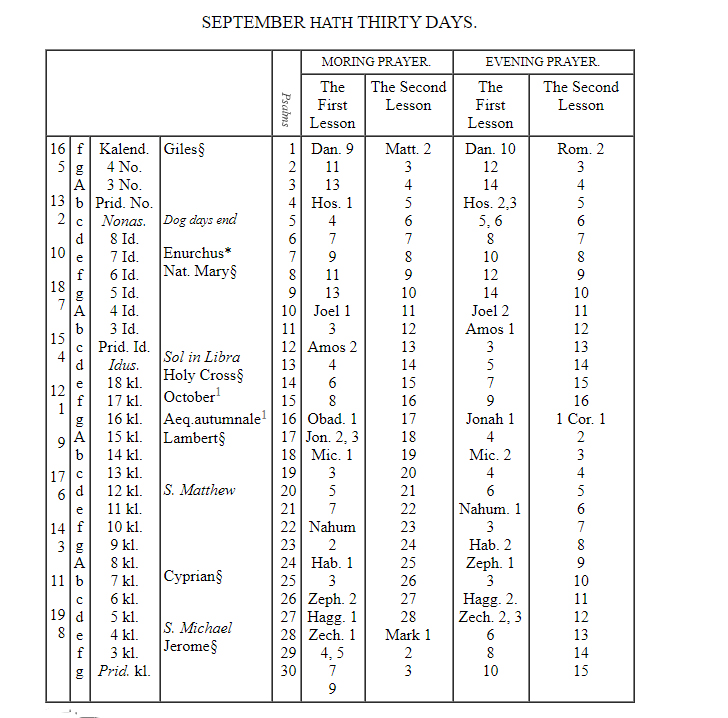

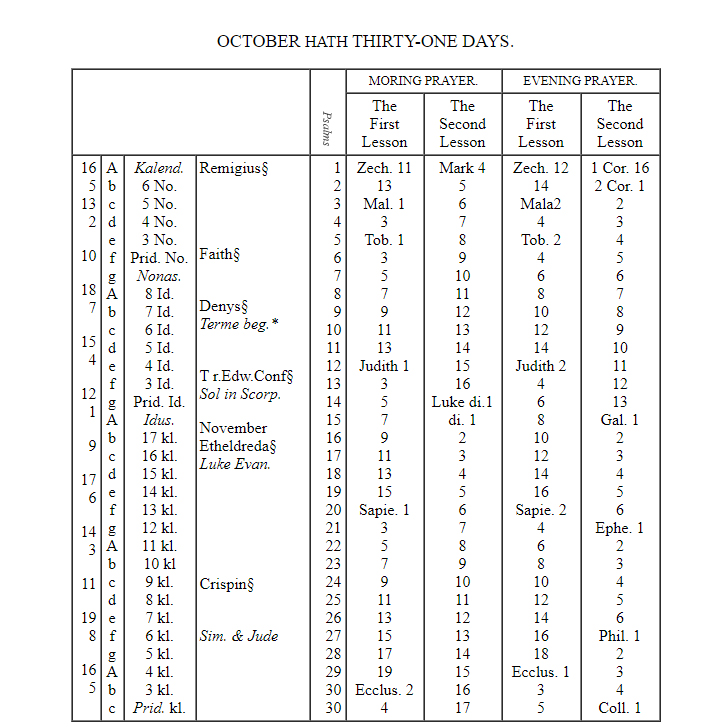

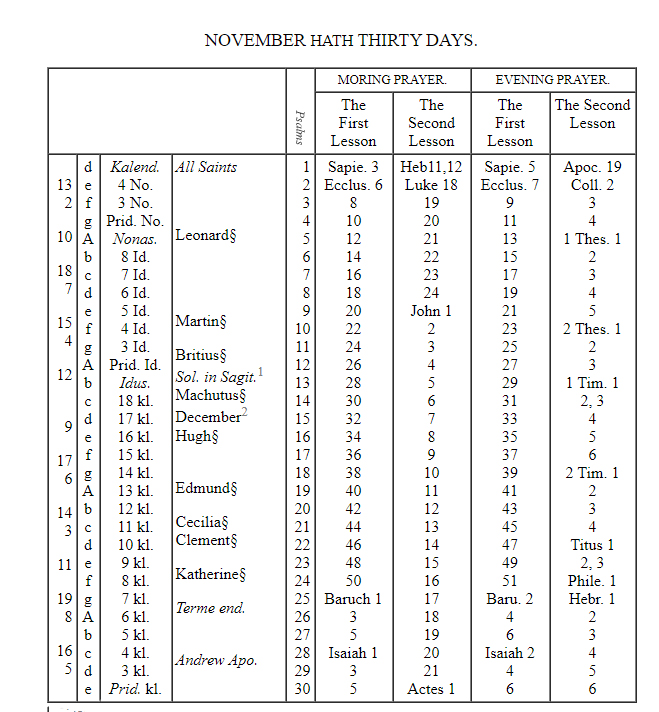

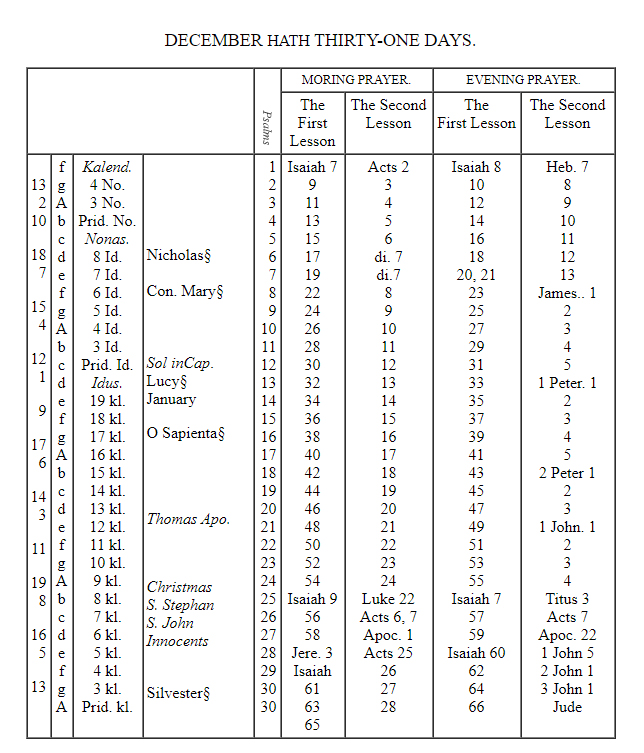

The second step is to determine which Old and New Testament Readings were used at Morning and Evening Prayer

THE ORDER HOWE THE RESTE OF HOLY SCRIPTURE (BESYDE THE PSALTER)

IS APPOINTED TO BE READDE.

THE OLD Testament is appointed for the fyrst lessons, at Morning and Evening prayer, and shal be read through, everye yere once, excepte certaine bokes and Chapiters, whiche be leaste edifying, and mighte beste bee spared, and therefore bee lefte unread.

The newe Testament is appointed for the seconde Lessons, at Mornyng and Evenyng prayer, and shalbe read over orderly every yere thryse, besyde the Epistles and Gospels: except the Apocalipse (Book of Revelation), out of the which there bee onely certayne Lessons appointed, upon diverse proper feastes.

And to knowe what Lessons shalbe readde every daye: fynde the day of the moneth in the Kalender folowing; and there ye shal perceyve the bokes and Chapiters that shalbe read for the Lessons, both at Mornynge and Eveninge prayer.

And here is to bee noted, that whensoever there bee any proper Psalmes or Lessons appointed for the Sondayes or for anye feaste moveable or unmoveable: then the Psalmes and Lessons, appointed in the kalender shalbe omitted for that tyme.

Ye must note also that the Collect Epistle and Gospell, appointed for the Sondaie shal serve al the weke after, except there fall some feast that hath his proper.

This is also to bee noted, concernyng the Leape yeares, that the xxv daye of February, which in Leape yeare is coumpted for two dayes, shal in those two dayes, alter nether Psalme nor Lesson: but the same Psalmes and Lessons, whiche be sayde the first daye, shall also serve for the second daye.

Also, wheresoever the beginnyng of any Lesson, Epistle or Gospel is not expressed: there ye muste beginne at the beginning of the Chapiter.

And wheresoever is not expressed howe farre shalbe read, there shall you reade to the ende of the Chapiter.

The third step is to check for exceptions to the Daily Office Calendar of Readings for Special Days

| Proper Lessons to Be Read for the First Lessons Both at Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer on the Sundays throughout the Year, and for Some Also the Second Lessons |

The fourth step is to consult the Tables for Finding Readings for Every Day of the Year for Morning and Evening Prayer

The fifth step is to determine if the day one is interested in is a Holy Day. If so, one needs to consult the Lectionary for Holy Communion to learn which readings were assinged for that particular Holy Day.

The assigned Prayers and Readings for Sundays and Holy Days are found in the section of the Book of Common Prayer entitled The Collects, Epistles, and Gospels, to be Used at the Celebration of the Lord’s Supper and Holy Communion through the Year.

This section is found in the Prayer Book immediately after the The Great Litany. It provides a Collect, or special prayer for the day, a reading from the Epistles, and a Reading from the Gospels for every Sunday and Holy Day on the Calendar of the Church of England. Those days are spelled out, as follows:

These to be observed for Holy dayes, and none other.

THat is to say, All Sundayes in the yeere. The dayes of the Feasts of the Circimcision of our Lord Jesus Christ. Of the Epiphany. Of the Purification of the blessed Virgin. Of S. Matthias the Apostle. Of the Annunciation of the blessed Virgin. Of S. Marke the Evangelist. Of S. Philip and Jacob Apostles. Of the Ascension of our Lord Jesus Christ. Of the Nativity of S. John Baptist. Of S. Peter the Apostle. Of S. James the Apostle. Of S. Bartholomew the Apostle. Of S. Matthew the Apostle. Of S. Michael the Archangel. Of S. Luke the Evangelist. Of S. Simon and Jude Apostles. Of All Saints. Of S. Andrew the Apostle. Of S. Thomas the Apostle. Of the Nativity of our Lord. Of S. Steven the Martyr. Of S. John Evangelist. Of the holy Innocents. Munday and Tuesday in Easter weeke. Munday and Tuesday in Whitsun weeke.

The sixth step is to assemble all the readings, together with the Collect appointed for the Day and locate where they come in the order of the worship services appointed for that day. One then can read through the service or sequence of services, placing the sermon one is interested in its particular spot, either in the service of Holy Communion or at the end of Evensong.

References

| ↑1 | David Griffiths, The Bibliography of the Book of Common Prayer: 1549 – 1999 (British Library, 2002), p. 6. |

|---|