When John Donne took up residence inside Paul’s Churchyard in the Deanery in 1621, he moved into a space that had been going through a series of significant changes over the past 100 years.

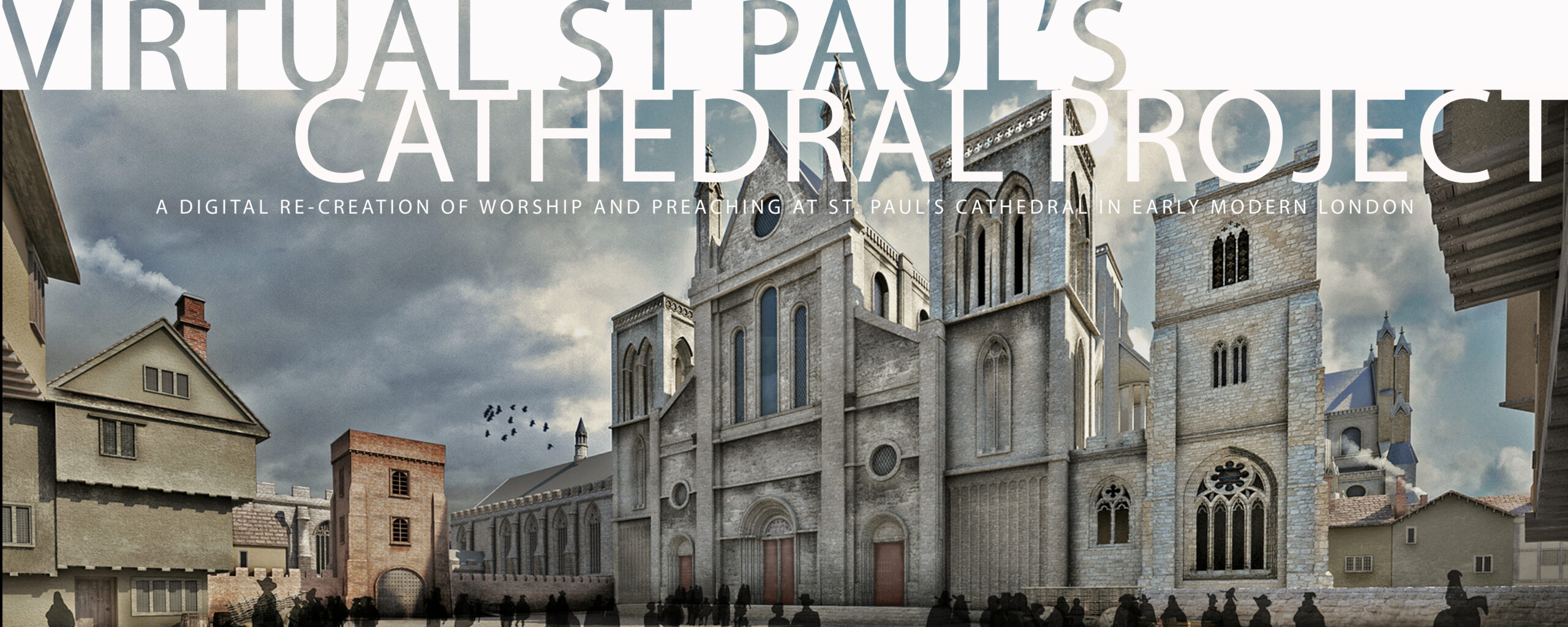

In the early modern period, St Paul’s Cathedral — even after its spire was destroyed by fire in 1561 — continued to loom over the London cityscape, a constant point of reference for anyone out and about in the growing commercial world of England’s largest city. During this period, London’s population grew from about 50,000 to 500,000 people, crowding the streets of the medieval City and spurring rapid expansion of its ever-growing suburbs.

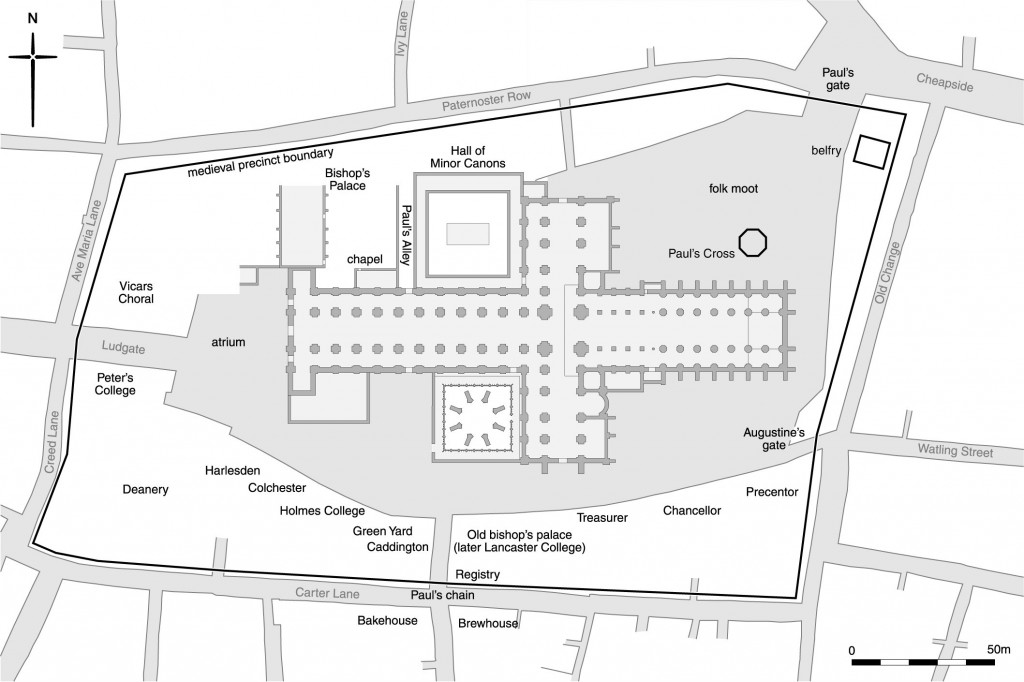

Surrounded by a wall, bounded to the north by Paternoster Row, to the east by Old Change Street, to the south by Carter Lane, and to the west by Ave Maria Lane, accessible only through through passages and gateways – notably Paul’s Gate, to the north, Augustine’s Gate to the east, Paul’s Chain to the south, and of course Ludgate itself to the west — medieval Paul’s Churchyard was a place set apart from the growing commercial city surrounding it.

St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1450. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011)

In 1500, the Churchyard was chiefly a place devoted to the practice of medieval Catholicism. With its daily round of worship services chanted in Latin, with its large numbers of chantry priests saying Mass for the repose of the souls of the departed, and its shrine to St Erkenwald drawing pilgrims from near and far, Paul’s Churchyard served as the religious center of this rapidly-growing city.

As a result, life inside the medieval Churchyard was almost totally devoted to maintaining the worship life of the Cathedral. Buildings surrounding the Cathedral provided housing for the Dean and the other three chief officers of the Cathedral’s Chapter of thirty Canons – the Treasurer, the Chancellor, and the Precentor. The Deanery was located on the southwest side of the Churchyard; the houses for the other three officers were located south of the south side of the Cathedral, between the Cathedral and Carter Lane.

St Paul’s Churchyard also provided group housing for the members of the Choir – the Vicars Choral, the Minor Canons, and the Choristers. Lodging for the Vicars Choral was at the west end of the Churchyard, north of Ludgate Street. The Minor Canons lived north of the Nave, between the Cathedral and Paternoster Street. The Choristers lived in the Almoner’s House, south of the Cathedral and adjacent to the Chapter House.

Also occupying lodging inside Paul’s churchyard were the Bishop of London, his family, and his core staff. Other employees of the Cathedral — the bell ringers, the custodians, the grave diggers, the Library staff, and the personal servants of the Dean, the Officers, and the Bishop of London may also have lived inside the Churchyard.

Since most of St Paul’s thirty Canons were non-residentiary — they had posts in parish churches in London and its environs — the four chief officers of the Cathedral bore full responsibility for the work of the Cathedral and the maintenance of the Cathedral’s fabric. The Dean of a cathedral was responsible for the overall internal management of the cathedral. He also was the chief liturgical officer of the Cathedral, responsible for ensuring that worship was conducted appropriately; he also had a prescribed role in worship services, especially on the principal festivals of the Church Year. The Dean also presided at meetings of the chapter of Canons (also known as Prebends at St Paul’s).

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Treasury. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Among the chief officers, the Treasurer was responsible for the cathedral’s fabric and furniture; he also provided bread and wine for the Eucharist as well as candles for illumination in the Choir. He also regulated the ringing of the bells and other similar activities. The Chancellor of the Cathedral had oversight of its schools, as well as of its other educational programs. The Chancellor was also in charge of the reading of Lessons at worship services and served as the secretary and librarian of the chapter. The Precenter was the priest responsible for regulating the musical portion of the services, providing housing for the singers, and making sure the organ, the vestments, and other material required for worship were available and in working order.This basic organization of the medieval Cathedral’s officers and staff persisted after the Reformation. Not surviving the Reformation, however, were the clergy who lived in St Peter’s College, Holmes College, and Lancaster College and who spent their days in the Cathedral’s chantry chapels, saying Mass for the repose of the souls of those who had endowed this practice. They constituted a significant number of residents; estimates of the number of priests living at St Peter’s College alone range as high as 54 men.

To enable them to do their work, chantry chapels lined the cathedral’s Nave and the side aisles of the Choir. At the cathedral’s east end stood the Shrine of St Erkenwald, the patron saint of London and the goal of pilgrimages to the shrine. While we are told that St Erkenwald did not attract the kind of attention among those who would go on pilgrimages that the Shrine of St Thomas Beckett did at Canterbury, he did have his devotees who made the journey up Ludgate Hill, through the entrances to the Cathedral’s interior, and around to the east end of the Cathedral to perform their devotions.

In spite of the sense one gets that the focus of attention for those living inside Paul’s Churchyard in the late Middle Ages was entirely on what one might call “Holy Work,” there were connections between the cathedral precincts and the larger city around it. People living in houses adjacent to the Churchyard were members of parishes whose churches were inside the Churchyard. St Gregory’s Church stood adjacent to the southwest front of St Paul’s Cathedral. St Faith’s Church was actually in the basement of the Cathedral, underneath the choir.

This map of parish boundaries shows the areas of London from which these parish churches drew their congregants; St Gregory beside St Paul’s drew folks from the south and west of the cathedral, while St Faith’s drew on residents who lived to the north and east of the cathedral.

The chief responsibility of a cathedral is maintaining the regular round of worship services, yet the cathedral itself had no formal congregation, since it was, in effect, the church of the entire Diocese of London, so, presumably, on many occasions the only people in the Choir for regular services were the cathedral’s clergy and its musicians. (Cathedrals are, of course, called cathedrals because they house the cathedra, or chair that is one of the symbols of the Bishop’s office. A formal seating of the Bishop in his cathedra, inside his cathedral, is part of the ceremony through which a new Bishop of a Diocese is installed. Nonetheless, they were, presumably, joined on occasions by visitors to the cathedral, especially pilgrims coming to worship at the Shrine of St Erkenwald.

The medieval cathedral’s role in the larger community is illustrated further by the fact that it was always on the path of the Lord Mayor of London’s annual procession through the city, as well as a part of the occasional royal procession as well. The churchyard was also the site of acts of public penance as well as for executions of those convicted of capital crimes. Citizens of London could also request burial in Paul’s Churchyard; later their bones would be unearthed and moved to the Charnel House in the northeast side of the Churchyard.

Nonetheless, the English Reformers found enough commercial and very worldly activity going on at St Paul’s and other churches in the country to make the financial corruption of the medieval church a chief target of their reforming energies. The chantry priests were supported by money left by the well-to-do in their wills so that Masses could be said so that God would count the good deed of saying Mass against the departed’s sentence of years in Purgatory, a doctrine the Reformers rejected out-of-hand. The Reformers also rejected the value for one’s salvation of activities like veneration of the saints, going on pilgrimages, owning relics of the saints, purchasing pardons and indulgences, and adoring paintings and depictions in stained glass of the saints.

The English Reformers found enough commercial and very worldly activity going on at St Paul’s and other churches in the country to make the financial corruption of the medieval church a chief target of their reforming energies. The chantry priests were supported by money left by the well-to-do in their wills so that Masses could be said so that God would count the good deed of saying Mass against the departed’s sentence of years in Purgatory, a doctrine the Reformers rejected out-of-hand.

The Reformers also rejected the value for one’s salvation of activities like veneration of the saints, going on pilgrimages, owning relics of the saints, purchasing pardons and indulgences, and adoring paintings and depictions in stained glass of the saints. For St Paul’s, a center for these practices, the consequences were significant. While the core organization of the Cathedral – its Chapter of Canons, its organizational structure of Dean, Precentor, Treasurer, and Chancellor, its staff of Minor Canons and Vicars Choral all remained. But the chantry chapels were torn down or abandoned, their clergy dispersed; the Charnel House and its chapel were torn down and the bones carted off; the Shrine of St Erkenwald was dismantled; the Cloister in the north central part of the Churchyard was demolished, stained glass windows were smashed; wall paintings were whitewashed over.

The financial cost to the cathedral soon became evident; the Cathedral’s spire was struck with lightning in 1561 and was never replaced. By the early years of the seventeenth century, people recognized that the fabric of the cathedral was in serious need of refurbishing, yet fundraising efforts never succeeded in bringing in enough money to secure the building.

There had always been unused space in Paul’s Churchyard, especially in the northeast quadrant, around the Paul’s Cross Preaching Station (see the Cathedral as shown in the Copperplate Map, above). As a result of the abandonment of chantry priests’ residences, buildings owned by the Cathedral could be put out for lease. The clearing away of the Chantry Chapel in the area around Paul’s Cross opened up even more space, making other changes possible.

The creation of new space made other changes possible, perhaps the most interesting of which is an event which took place in 1554, five years after the dissolution of the chantry system, when the Stationers Company took over the property of the now vacant Peter’s College and established the Stationers Hall, which served as their headquarters until they moved to Ave Mary Lane in 1606. The existence of the Stationers Hall in this space reflects the technological development of the printing press, given organizational form in a system of production to support the cultural shift toward printed books from handwritten manuscripts through the development of the book trade in early modern London.

As a result of the development of printing, the world of a new kind of commerce moved aggressively into Paul’s Churchyard. The location of the Stationer’s Hall in the abandoned residence of chantry clergy in Peter’s College encouraged the development of the book trade in Paul’s Churchyard. This started in the area around the Paul’s Cross preaching station with sales from horse-drawn carts, then from freestanding bookstalls, then from the ground floors of mixed use houses that sprung up around the sides of Paul’s Churchyard, then along the sides of the North Transept.

Interesting to note that when the Stationers Company moved out of the former Peter’s College, the property next became the Feathers Tavern – surely a telling transformation in the concept of the sacred, as the site of dwelling for priests who spent their days consecrating bread and wine eventually became a place for selling a dramatically different kind of food — whatever is the early modern equivalent of fish and chips, or bangers and mash, or Scotch eggs, with good English ale to wash it down.

Such transformations outside the cathedral – constituting, as they do, the flourishing of a commercial space in a formerly sacred space – need to be seen as reflecting a shift away from an understanding of the Churchyard as the reserve of the sacred to an understanding that accepted the mix of the commercial and the sacred, all in one space. Regardless of the commercial implications of the ways that sacred activities were funded in the medieval arrangement of space, the post-Reformation arrangement located the religious alongside the commercial spheres of activity.

This distinction was blurred a bit by the fact that a substantial percentage of books sold in the bookshops of Paul’s Churchyard were on religious topics, whether they were Bibles or service books like the Book of Common Prayer, or printed collections of sermons, or devotional works. Sales of printed sermons could improve the economic life of their preachers, but many clergy refused to have their sermons printed out of a sense that the transition from spoken word to print publication detracted from the spiritual efficacy of the sermon delivered rather than expanded the scope of the sermon’s audience.

In any case, in the bookshops of Paul’s Churchyard the religious text sat next to the secular text in what to some must have seemed a significant juxtaposition. This narrative of the growing mix of of the sacred and the secular in Paul’s Churchyard is further supported by the consequences of the Reformation inside the cathedral. For, post-Reformation, the Nave of St Paul’s was no longer needed to provide space for festive religious processions, or for side altars where the Chantry priests could ply their trade. So this space – the largest enclosed space in London – became available to be repurposed for other activities.

While the Nave of the medieval Cathedral had seen limited commercial activity of various kinds. After the Reformation, however, only the occasional procession through the Nave — of the Lord Mayor of London and his entourage or of the clergy of the Province of Canterbury gathering for a meeting of Convocation — served as a reminder of what had been. For the post-Reformation Nave became in the next few decades the infamous Paul’s Walk, where Londoners of fashion came to see and be seen, and where lawyers and prostitutes gathered seeking clients “Paul’s Walk,” wrote John Earle, “is the land’s epitome,” but not a place in which worship was (or was able to be) conducted:

It is a heap of stones and men, with a vast confusion of languages . . . . . The noise in it is like that of bees, a strange humming or buzz, mixed of walking, tongues, and feet. It is a kind of still roar or loud whisper. It is the great exchange of all discourse, and no business whatsoever but is here stirring and afoot. . . . . It is the general mint of all famous lies, which are here, like the legends of popery, first coined and stamped in the church. All inventions are emptied here, and not few pockets. 1

So our search for the sacred inside St Paul’s thus shifts to the Choir of the Cathedral, seen here, in our reimagining of it for the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project. Here, Divine Service was sung, morning and evening; here, the Great Litany was chanted; here, Holy Communion was celebrated on Sundays and Holy Days. Here, preachers appointed by the Bishop of London preached in the mornings; here, the Dean of the cathedral or his appointed replacement preached in the afternoons.

The chief responsibility of a cathedral is maintaining the regular round of worship services, yet the cathedral itself had no formal congregation, since it was, in effect, the church of the entire Diocese of London. The emphasis in the post-Reformation Church of England was on the nation united in prayer, in praise, in sacramental union of “the mystical bodie of thy Sonne, which is the blessed company of all faithful people.” St Paul’s Cathedral was the functioning symbol of the Diocese of London, even as Canterbury Cathedral was the functioning symbol of the Province of Canterbury and York Cathedral was the functioning symbol of the Province of York. 2

No surprise, then, that the Puritans, who were determined to divide the English into the elect and the damned, sought after the Civil War to eliminate the cathedral system. Presbyterians, on the grounds that they could not find the Cathedral system in the Bible, closed the buildings. St Paul’s was stripped of its furniture; there are legends that Oliver Cromwell quartered his troops’ horses inside the building.

The official formularies of the Church of England gathered the individual into the parish community, the parish community into the diocesan community, the diocesan community into the Provincial community, the Provincial communities into the nation at prayer. Justification was by faith, the true and lively faith; evidence for one’s having the true and lively faith was found outside of oneself, in the doing of good works of charity to one’s neighbors, thus in one’s relationships with one’s fellow parishioners.

The Puritan party, as we will explore elsewhere, sought signs of one’s election within; the worship of one’s parish was, presumably, not to support prayer in unity with one’s parishioners but only to help one in the search within, thus was ancillary to what was important, not central to it. The Puritans who came to power after the defeat of Charles I sought a national church on the Presbyterian model, but the disintegrating trajectory of Puritanism led not to national unity on a new model of religious authority, but to further disintegration into congregationalism, then into the multiplication of diverse sects and cults, a trajectory that continues today.

REFERENCES

- From John Earle’s Microcosmographie, cited from John Dover Wilson, Life in Shakespeare’s England (London, 1964), 124.

- For more on the English cathedral in the early modern period, see Stanford E. Lehmberg, English Cathedrals: A History (2005), Cathedrals Under Siege: Cathedrals in English Society, 1600–1700 (1996), and The Reformation of Cathedrals: Cathedrals in English Society (2016).