This section of the Cathedral website offers a walking tour of Paul’s Churchyard with the goal of identifying particular sites of historic significance and clarifying the relationships among the various structures and locations within the Churchyard. To get an overview of the Exterior Model, go here for a whirlwind tour via the fly-around video of the entire Churchyard.

We begin our tour on the northeast side of the Churchyard, standing outside the Churchyard at the intersection of Paternoster Row and Cheapside, then entering into the Churchyard by way of Paul’s Gate.

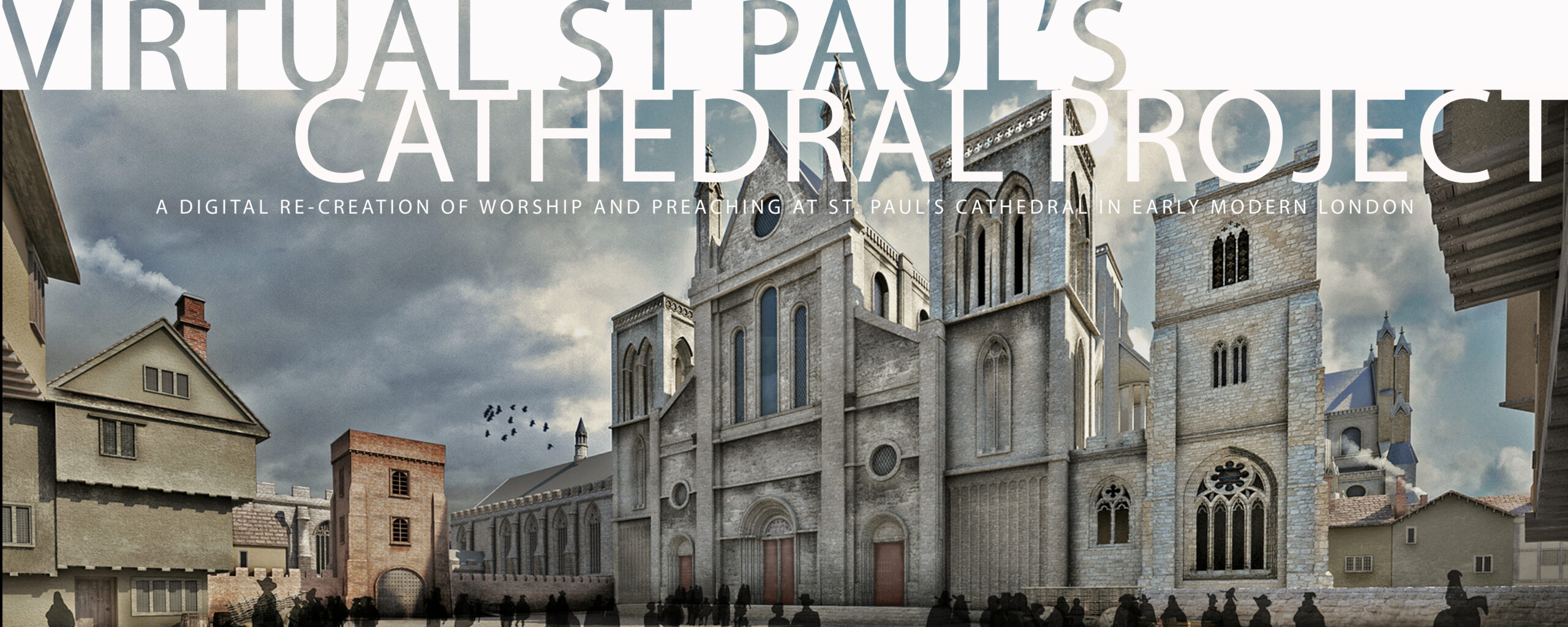

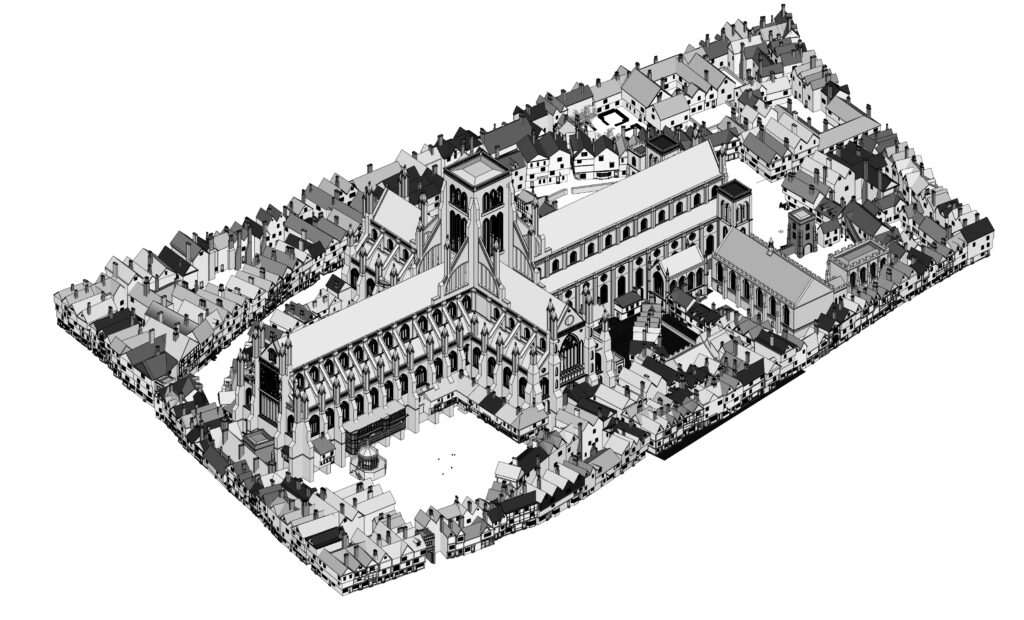

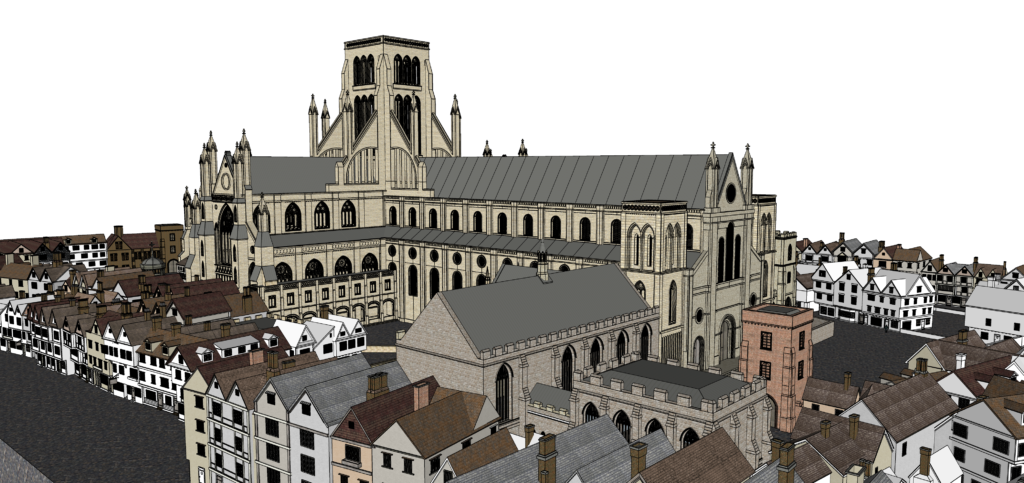

St Paul’s, the Visual Model, from Above. From the Exterior Model, created by Joshua Stephens, Grey Isley, Eli Simaan, Andrew McCall, Cameron Westbrook, Smith Marks, and Austin Corriher

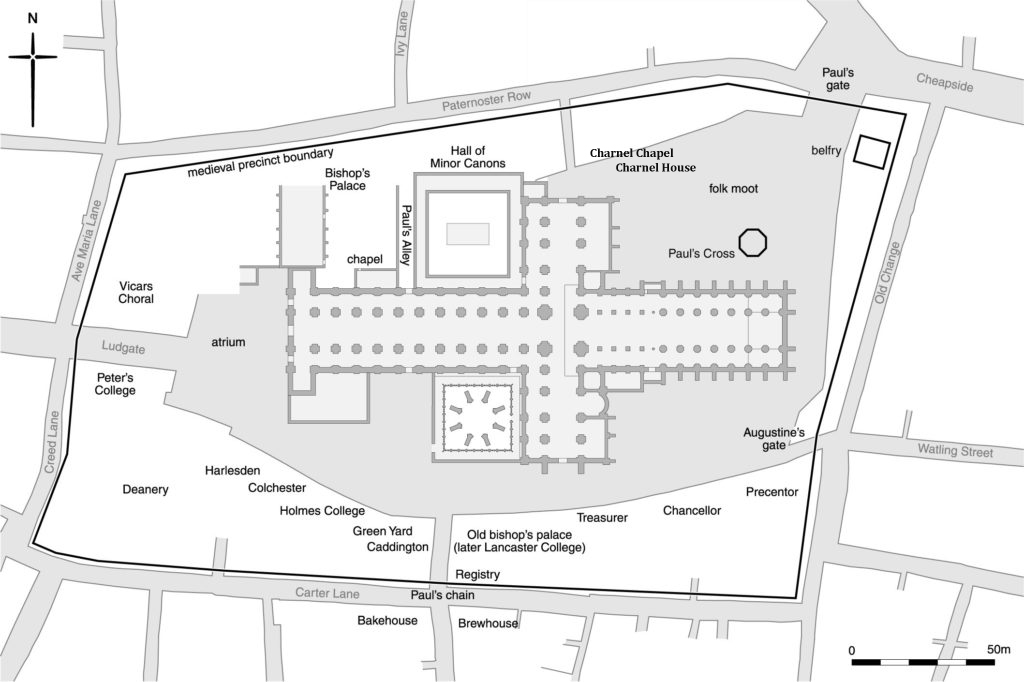

St. Paul’s Churchyard around 1450. Image courtesy John Schofield, from St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (2011).

You can enter Paul’s Churchyard either on a cloudy day in November of 1622 or on a sunny day in April of 1624. If you prefer November, go here to the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, where you can spend two hours listening to John Donne deliver his Paul’s Cross sermon for Gunpowder Day, November 5th, 1622. If you prefer April, remain here to celebrate Easter with John Donne and other members of the Cathedral staff, along with the Lord Mayor of London and his entourage.

St Paul’s Churchyard, Paul’s Gate. From the Visual Model rendered by Jorday Grey.

St Paul’s Churchyard, Paul’s Gate. From the Visual Model rendered by Austin Corriher.

Either way, you arrive in the section of Paul’s Churchyard known as the Cross Yard, where you will find the Paul’s Cross preaching station. If you are here in November, Donne’s sermon is in progress. If you are here in April, you are not here on Easter Sunday but a Sunday in Lent or a Sunday after Easter, when someone else is preaching a sermon at the Cross.

To the right of Paul’s Cross is the Sermon House, built to allow dignitaries to sit in covered seats while listening to the sermons preached at the Cross. In front of Paul’s Cross are benches which could be reserved for a fee for folks who wished to sit during the two-hour-long sermons. During the week, these benches were stored in the North Transept of the Cathedral.

Paul’s Churchyard, looking east, from the west.From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Jordan Gray.

Paul’s Churchyard, looking east, from the west. .From the Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens, rendered by Austin Corriher

Behind Paul’s Cross in the April version is a three-story brick building representing St Paul’s School, founded in 1509 by John Colet, then Dean of the Cathedral. The inclusion of St Paul’s School marks one of the major revisions in our Exterior Model between the version of 2013 and the version of 2021. Early in Donne’s tenure as Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, the poet John Milton was a student at St Paul’s School before he left for Cambridge University in 1623. In Milton’s poem “Il Penseroso,” the speaker remembers worship at the Cathedral, thus:

But let my due feet never fail

To walk the studious cloister’s pale,

And love the high embowed roof,

With antique pillars massy proof,

And storied windows richly dight,

Casting a dim religious light.

There let the pealing organ blow,

To the full-voic’d quire below,

In service high, and anthems clear,

As may with sweetness, through mine ear,

Dissolve me into ecstasies,

And bring all Heav’n before mine eyes.

– John Milton, “Il Penseroso,” 155-166

Behind Paul’s Cross in both images are mixed-use structures housing booksellers on the ground floor and living quarters for the booksellers above them. These were constructed in the years after the Dissolution of the Monasteries when the demolition of the medieval Charnel House and Charnel Chapel provided space for new construction. [1]See Thomas J. Farrow (2021), “The dissolution of St. Paul’s charnel: remembering and forgetting the collective dead in late medieval and early modern England, Mortality,” DOI: … Continue reading

Our purpose in juxtaposing these images is to draw attention to the differences in style of depiction between the houses in the Paul’s Cross model and the same buildings in the Virtual Cathedral model. The exterior walls of the houses in the Paul’s Cross model are in the style we generally associate with houses of this period, with the structural beams of the buildings exposed to the weather and painted black, with white-painted plaster covering only the spaces between the beams. These same houses in the Cathedral model show plaster covering the entire exterior structure and painted in various pastel shades.

St Paul’s Cathedral from the Northwest (Pre-rendered state). From the Visual Model, built by Grey Isley.

Go to the Constructing the Visual Model page for a discussion of the reasons for this change; for now, please note that it is truly rare for any surviving early modern image of houses to depict them with exposed structural beams. Yet one would think that such a significant visual element in the exterior of early modern houses that still survive would have made it into 16th or 17th century depictions of them.

One is in fact tempted to believe that the exposed beams with which we are so familiar as a feature of Elizabethan houses are an artifact of a much later restoration of these early modern structures rather than a characteristic of their original design.

Having faced eastward in the Cross Yard, we now turn westward for our last bi-seasonal depiction, with the grey days of November 1622 yielding to the bright sunshine of April 1624. The section of the Cathedral we see here is the Gothic part of the building, built in the 1400’s after the original Norman Choir was torn down and this Gothic structure built in its place.

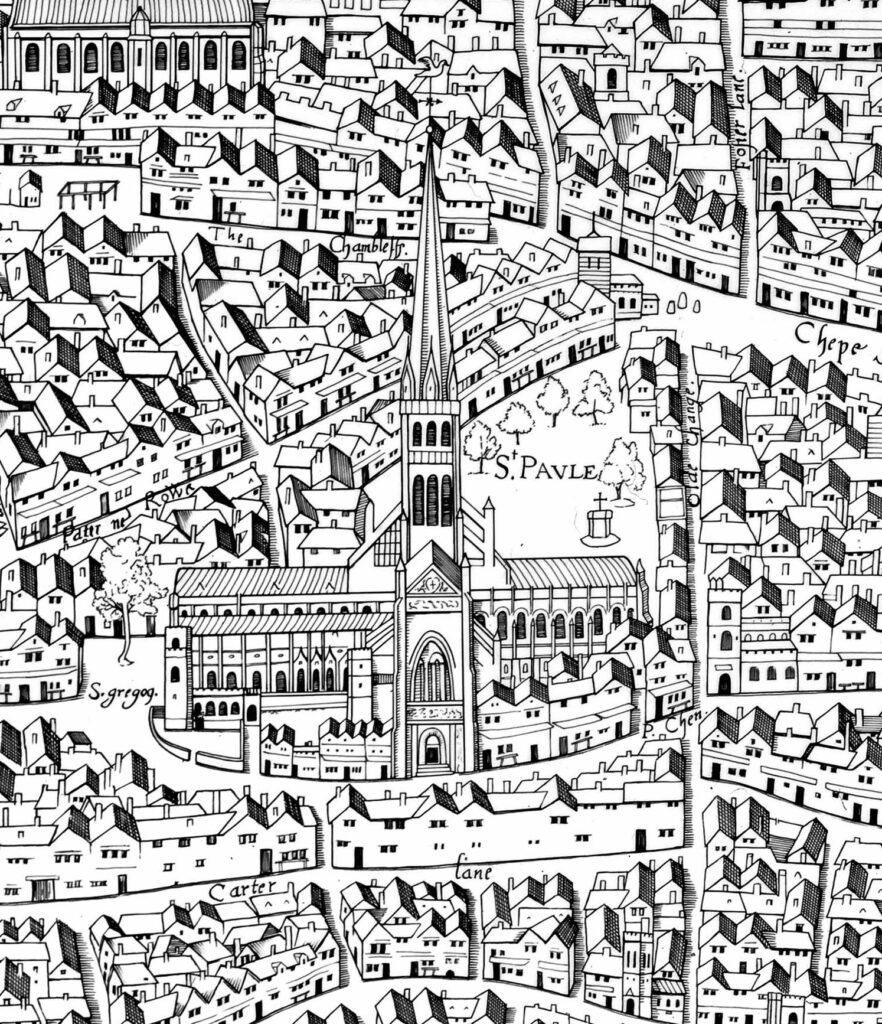

This point on our tour is as good a time as any to draw attention to the fact that in our model St Paul’s tower has no spire. The Cathedral had one, but it was struck by lightning and set afire in 1561. After the fire was put out, the spire was never replaced. The image below, from the Copperplate Map of London, shows the Cathedral’s spire in all its pre-1561 glory.

As we move further westward around the North Transept (and move upward for a better view), we see the full north front of the Transept, as well as the north end of the Cathedral’s Library, a long, narrow building tucked against the west side of the North Transept.

We also see an open area where the Cathedral’s Cloister was located before it was torn down during the Reformation. This space was soon filled in with additional housing. Moving further westward, we see emerging the Great Hall of the Bishop’s Palace. We also see the original Nave of the Cathedral, built in Norman/Romanesque style during the 1100’s.

As we return to the ground and move closer to the Palace, we see the Bishop’s Chapel against the northwest wall of the Cathedral. This is where John Donne was ordained both deacon and priest on January 23rd, 1615, in violation of the Canons of the Church of England, which specified that at least six months should elapse between one’s ordination to the diaconate and one’s ordination to the priesthood. But King James wanted Donne ordained, and James was Supreme Governor of the Church of England. And so it was done, by John King, Bishop of London.

We also see, in this image, the shops of artisans and craftspeople that were built during this period of time.

Moving further westward, our journey takes us into the forecourt of the Cathedral, where we see, to our left, the Palace of the Bishop of London, with its courtyard, its Great Hall, and other buildings where horses were stabled and the work of the Diocese of London was carried out.

If we approached the Cathedral from further west, perhaps from Westminster, we would come into the City of London through Ludgate and proceed eastward, approaching the Great West Front via a street lined on both sides with buildings.

To the left is the building housing the Vicars Choral, a group of professional musicians who were laymen, not clergy. There were places for six Vicars Choral on the staff of the Cathedral in Donne’s day, although the actual number varied from time. The Vicars Choral shared with the Minor Canons and the Choir Boys the work of preparing and performing the choral parts of the Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer, as well as other services of the week and Church Year.

To the right is Peter’s College, which in the Middle Ages was a domicile for priests who made their livings saying Mass for the repose of the souls of the well-heeled dead. Shortly after the Reformation, the Stationers Company had its offices in this building, but they soon moved north to another building located outside the Churchyard, in Ave Maria Lane. In Donne’s time as Dean, at least part of the space in this building was occupied by a pub.

As we move further east into the courtyard in front of the Cathedral, we see the Great West Front, which we see in two views. Th first view (above) shows the West Front in the cool light of morning, wile the second view (below) shows the West Front in the warm light of afternoon.

There are actually no surviving full-scale images of the West Front before the ones by Wenceslaus Hollar, but they show the West Front after Inigo Jones transformed it by covering it with a neo-classical façade some years after Donne died, making them useless for our purposes. So our version of the West Front is an invention, albeit not a totally ungrounded invention; see the discussion of how we did this on the Construction page of this website.

To the left of the West Front is, of course, the Bishop’s Palace, already noted; to the right is the tower of St Gregory’s parish church, the church for many of the people who lived inside the Churchyard.

If we turn right from our position before the West Front and go down a long passageway, we will arrive at the Deanery, where Donne lived from 1621, when he became Dean of the Cathedral, until his death in 1631. Given the fact that St Gregory’s is much closer to the Deanery than is the Choir of St Paul’s, it seems likely that when Donne mentions, in his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, that he was able to hear a congregation singing a Psalm while he is sick in his bedchamber in the Deanery, he is describing sounds coming from St Gregory’s Church.

Our image of the Deanery is based on information about the Deanery that our colleague John Schofield found in the London Metropolitan Archives. In our image of the Deanery we see the Dean’s Garden; on the other side of this part of the building were the Deanery’s main entrance as well as stables for his horses.

Returning to the Cathedral, and, again, taking flight, we can see the full length of the Cathedral’s south side including, especially the Chapter House and the Almoner’s House. We now know, thanks to the research of Roze Henschell, that the boys who were members of the St Paul’s Choir lived in this house. During a couple of periods of time, they also performed plays in this space, but not while Donne was Dean of the Cathedral.

Moving further eastward, we notice the Cathedral’s Chapter House and the Cloister around it. The Chapter House was the part of the Cathedral in which the Dean and the 29 other Canons comprising the Chapter of Clergy for the Cathedral had their official meetings.

As we move eastward down the south side of the Cathedral, we move into an area where the Officers of the Cathedral had their residences.

St Paul’s Cathedral from the South. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Among the houses shown here closest to the Cathedral were the official residences of the Cathedral’s Treasurer, the Chancellor, and the Precentor, the three chief officers of the Cathedral staff, along with the Dean. For details about who they were and what their duties were, see the “Officials” section of this website.

As we continue our journey eastward, we can see a small building nestled against the intersection of the South Transept and the Choir. This is the Cathedral’s Treasury. Interestingly, the lower half of this building is actually underground, presumably a security measure to protect the Cathedral’s financial holdings from potential theft.

As we continue our journey eastward, we are approaching Augustine’s Gate, an opening into the Churchyard from the east, from Old Change Street. We can look back to see the east face of the South Transept as well as the south side of the Choir.

The density of housing inside the Churchyard is at least partially a result of the fact that the population of London grew dramatically in the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth century, growing from about 100,000 in 1550 to over 200,000 by the early years of the seventeenth century.

To conclude our journey around St Paul’s Cathedral, we take one final look back through Augustine’s Gate before we head eastward through the Gate onto Old Change Street. We then head north on Old Change Street until we are directly behind St Paul’s School. Here, we take flight one last time so that we can look westward for a last lingering view of the East Front, the Great Rose window, St Paul’s truncated tower, and the west side of the City of London.

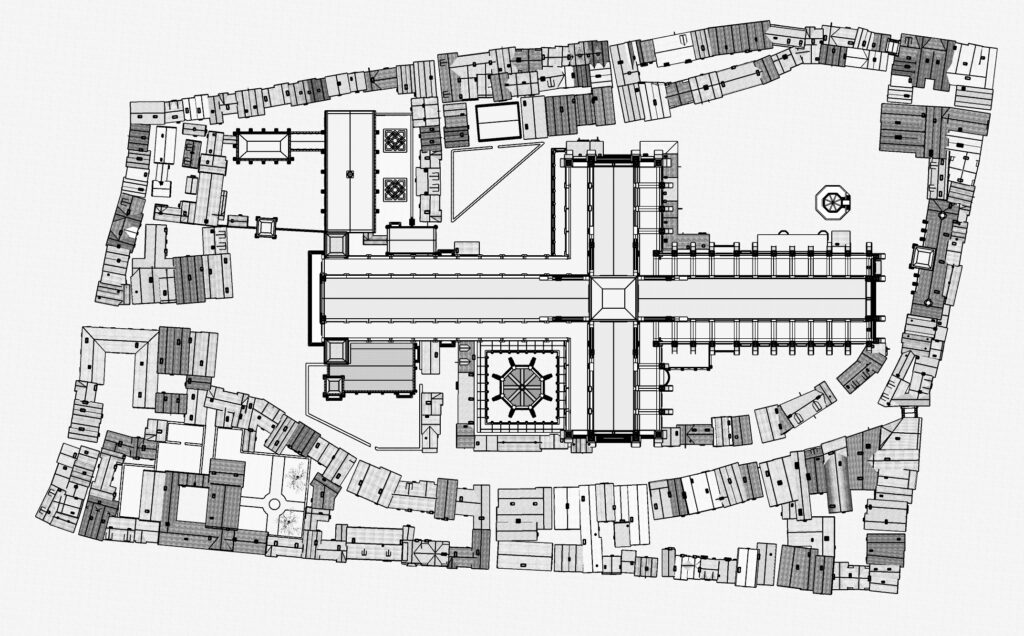

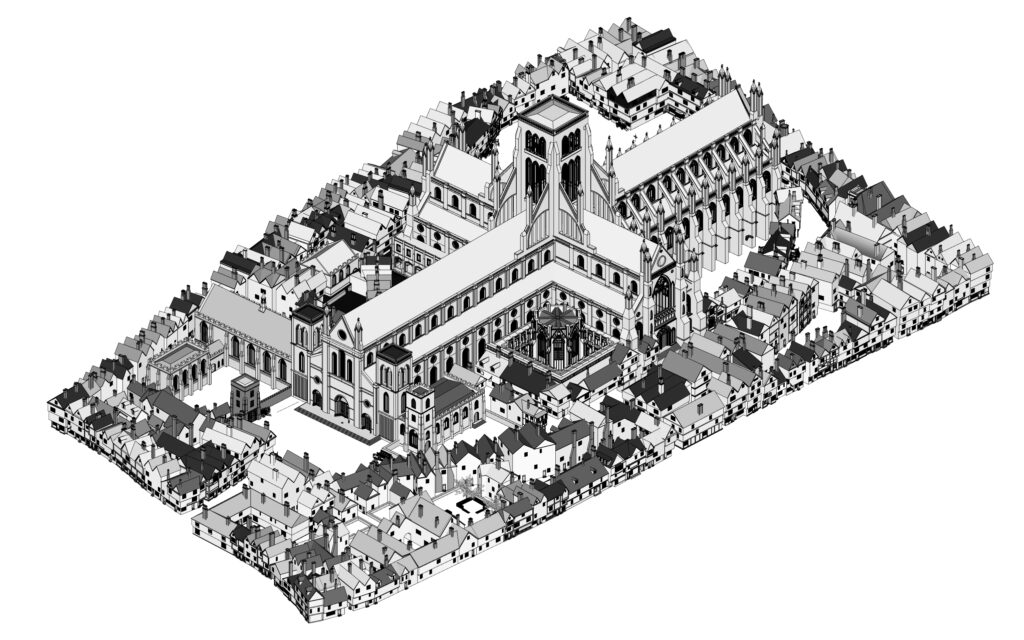

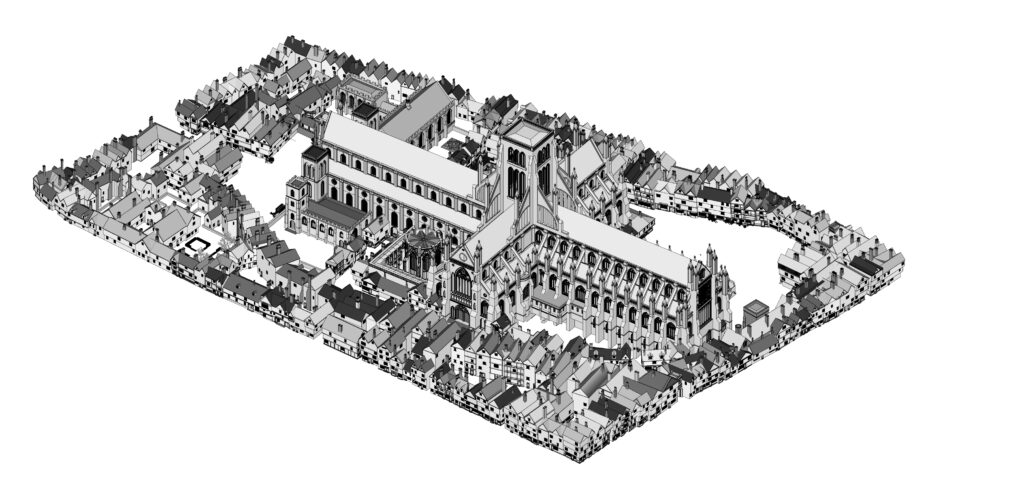

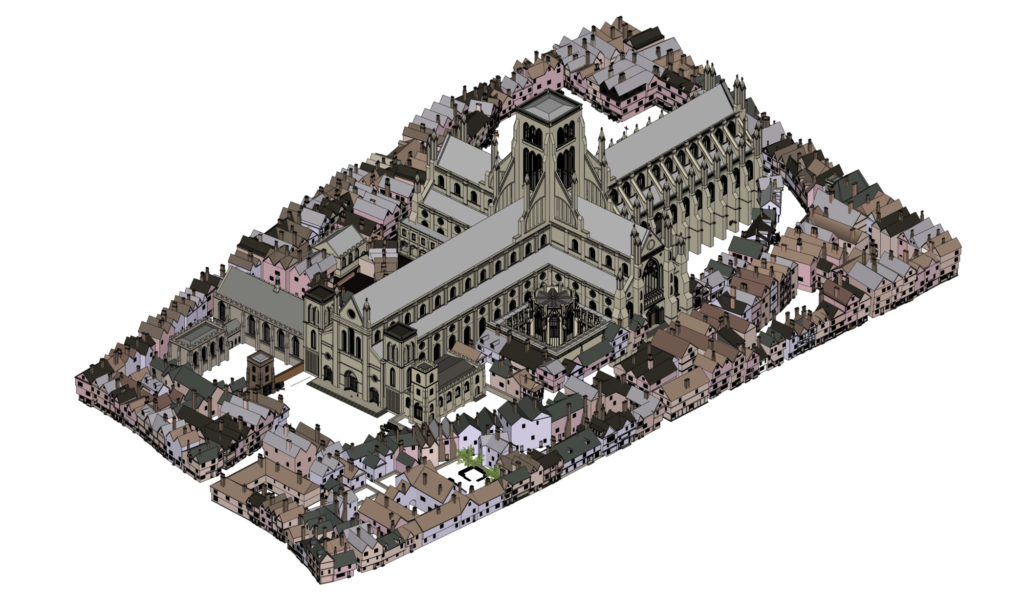

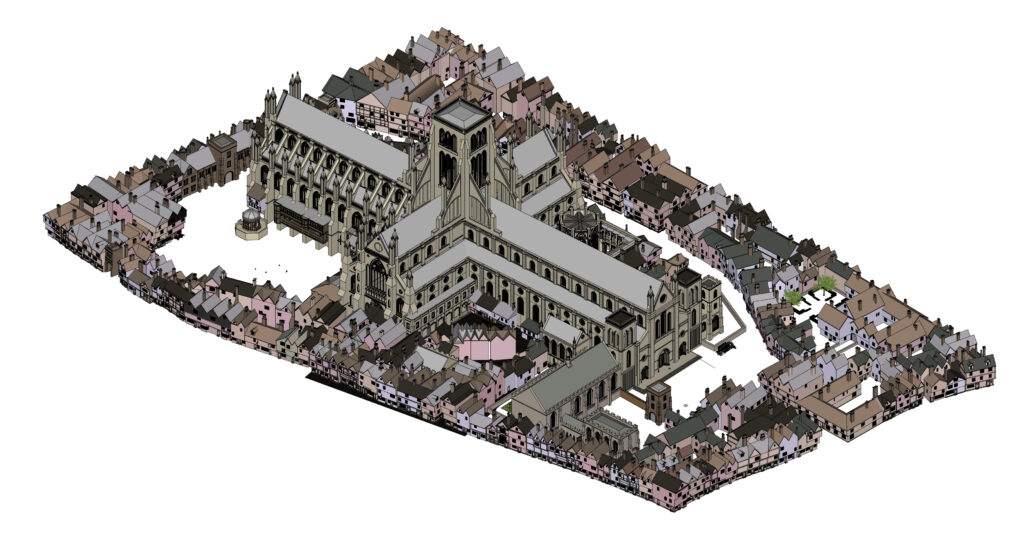

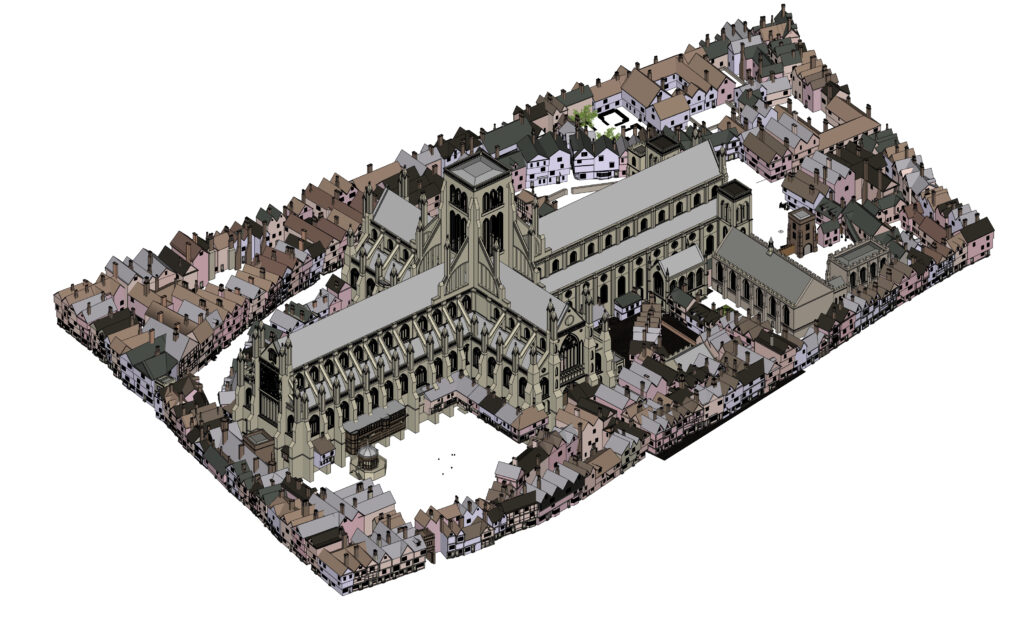

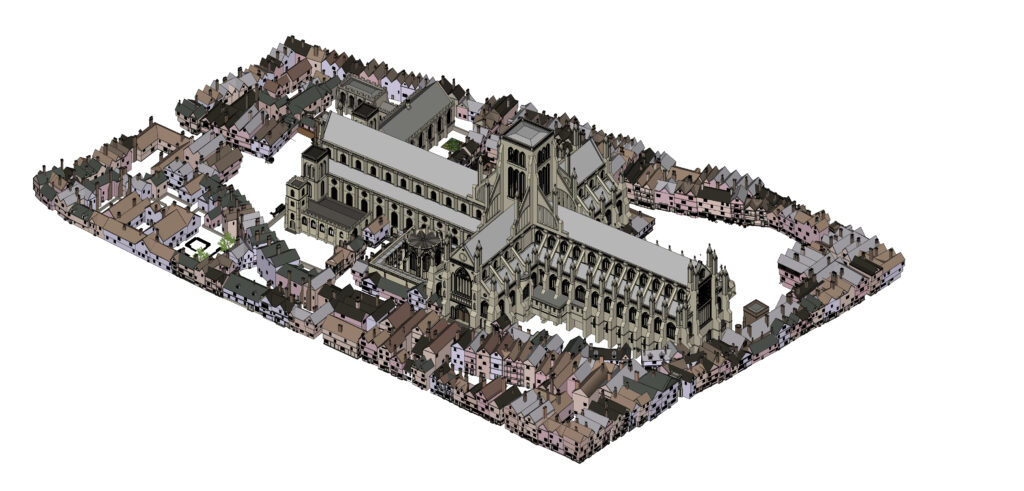

To help us integrate the specific details of the External Model into a sense of the larger whole, here are overhead views of St Paul’s Cathedral from four angles.

The first image shows us the Cathedral and Churchyard from the Southwest.

The second image takes us around to the north, to show us the Cathedral from the Northwest. From this angle we can see the Bishop’s Palace in the foreground, with the Cross Yard and Paul’s Cross in the background.

The third image takes us around to the east, to show us the Cathedral from the Northeast. From this angle we can see the Cross yard and Paul’s Cross in the foreground, with the Bishop’s Palace in the right background. foreground, with the Cross Yard and Paul’s Cross in the background.

Finally, we move around to the southeast, where we see the Cathedral and Churchyard from the southeast, with the South Transept and south side of the Choir in the foreground. Nestled at the intersection of the South Transept and the Choir is the Cathedral’s Treasury. The houses in the foreground include the houses for some of the Cathedral’s major Officers — the Treasurer, the Chancellor, and the Precentor.

To put all this information about the buildings around the Cathedral in Paul’s Churchyard, go to the fly-around video page and watch all this information fall into place.

References

| ↑1 | See Thomas J. Farrow (2021), “The dissolution of St. Paul’s charnel: remembering and forgetting the collective dead in late medieval and early modern England, Mortality,” DOI: 10.1080/13576275.2021.1911976“ |

|---|