There are clearly continental influences on the English Renaissance composers and certainly we know that Byrd for instance, knew music by earlier composers Diamante and Gomber and so on, the rather more refined continental polyphony. But there’s certainly a more distinctive English style, harmonically, and the use of particularly, well like bluesy notes, the flattened seventh, the English cadence they’re called. And I think this progression is very clear from the very florid style of the earlier composers such as John Taverner and Christopher Tye in his Latin music but running through Tallis more of a transitional figure, perhaps, leading up to the more refined polyphony of Byrd. But to my mind it all reaches up to it’s glorious flowering in the slightly later composers Orlando Gibbons particularly, whose music just seems to me to be so mellifluous, so melodic. It’s sort of effortless in every sense, through to the more madrigalian composers such as Thompkins and Wilkes, who respond to the text in a perhaps more dramatic way than composers such as Gibbons and Byrd did do in their own time. [1]From an interview in 2003, go here: http://music.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/0401_st_pauls/scott.shtml

— John Scott, Choirmaster, St Paul’s Cathedral

The Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral during Donne’s tenure as Dean consisted of 18 adults and 10 boys. Twelve of the adults — the Minor Canons — were clergy, while the other ten — the Vicars Choral — were laymen. The ten boys, under the supervision of the Master of Choristers, sang the soprano, or treble, parts, while the men sang the bass, tenor, and soprano parts. [2]For more on Cathedral music post-Reformation, see Jonathan Willis, Church Music and Protestantism in Post-Reformation England (Ashgate, 2010), p. 133.

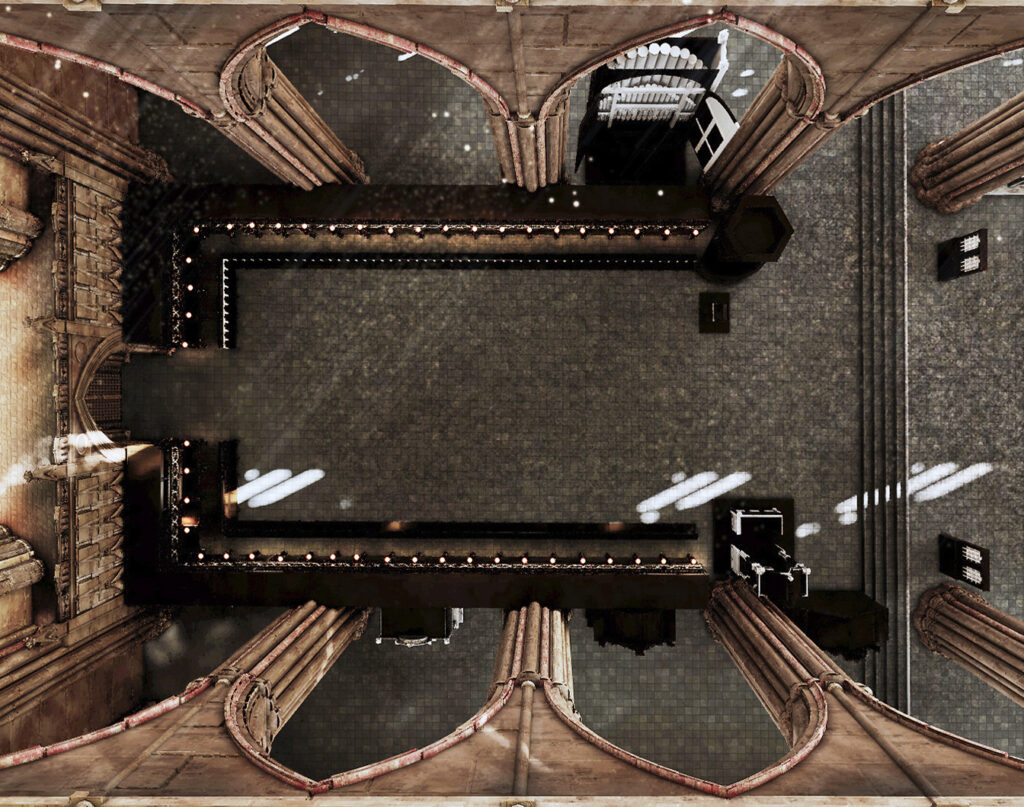

The cathedral’s primary source of musical accompaniment was the Great Organ, a description of its likely configuration has been supplied for us by Roger Bowers, music historian of Jesus College, as follows:

We have no surviving detailed account of the Great Organ at St Paul’s Cathedral.

“Perhaps something akin to the double organ at York Minster of 1632 (builder: Robert Dallam) might seem suitable to serve as at least a starting point. Notional standards of length were 10 ft. and 5 ft. (rather than today’s 8 ft and 4 ft.); if I understand the technicalities correctly, Diapasons sounded at 10 ft pitch, Principals at 5 ft. ‘Tin’ was conventionally an alloy of tin (around four parts) and lead (around one part).

York: Great organ (each rank of 51 pipes):

1. Open Diapason I (tin) [show pipes]

2. Open Diapason II (tin) [show pipes]

3. Diapason (wood)

4. Principal I (tin)

5. Principal II (tin)

6. Twelfth to the Diapason

7. Small Principal (tin)

8. Recorder (‘unison to the said Principal’)

9. Twenty-second

St Paul’s ‘Chaire’ department. Burward’s contract for Salisbury records the St Paul’s ‘Chaire’ department as then consisting of five ranks, of which three were identified as:

1. Stopped Diapason (wood)

2. Principal (metal)

3. Flute (wood)

Dallam’s ‘Chaire’ organ at York (each rank of 51 pipes) consisted likewise of five ranks:

1. Diapason (wood)

2. Principal (tin) [show pipes]

3. Flute (wood)

4. Small Principal (tin)

5. Recorder (‘unison to the voice’) (tin).

The happy congruence between what we know of the St Paul’s ‘Chaire’ department and the specification of the York ‘Chaire’ department suggests that all five of the St Paul’s ranks may have matched closely those at York; and this in turn suggests that the St Paul’s Great department is unlikely to have been very significantly different from that of York.”

There being no early modern English organs still in existence for us to use, the part of the organ at St Paul’s Cathedral in our recordings is played by an electronic recreation of the organ found in the Holy Trinity church in Smecno, in the Czech Republic. Built around 1587, this organ is the oldest preserved and playable organ in the Czech Republic.

Standing in for the organists at St Paul’s (John Tomkins, Adrian Batten from 1626, and Martin Peerson also from 1626), are Richard Pinel or the Organ Scholars at Jesus College Dewi Rees and Jordan Wong. The software for this electronic organ recreation was created by the Sonus Paradisi Virtual Pipe Organ Project, running on Hauptwerk Virtual Pipe Organ Software.

Musical selections playable from links below include the service music — Canticles and Anthems sung by the Choir and Organ Voluntaries played during the services — from our recreations of worship services found on other pages of this website.

The Tuesday after the First Sunday in Advent

Morning Prayer

Venite – Plainchant

Te Deum (Short Service) – Thomas Tallis

Benedictus (Short Service) – Thomas Tallis

Anthem

If ye love me – Thomas Tallis

Organ Voluntary

Evening Prayer

Magnificat (4th Service) – Adrian Batten

Nunc Dimittis (4th Service) – Adrian Batten

Anthem

Deliver us, O Lord God – Adrian Batten

Organ Voluntary

Easter Day

Morning Prayer

Christ rising again – William Byrd

Te Deum (Short Service) — Thomas Tallis

Jubilate Deo (Second Service) – Orlando Gibbons

Anthem

Sing Joyfully – William Byrd

Organ Voluntary

Holy Communion

Creed – Thomas Morley

Christ our Paschal Lamb – Adrian Batten

Organ Voluntary

Evening Prayer

Magnificat (Second Service) – Orlando Gibbons

Nunc Dimittis (Second Service) – Orlando Gibbons

Anthems

We praise thee, O God – Orlando Gibbons

O Praise the Lord – Adrian Batten

Organ Voluntary