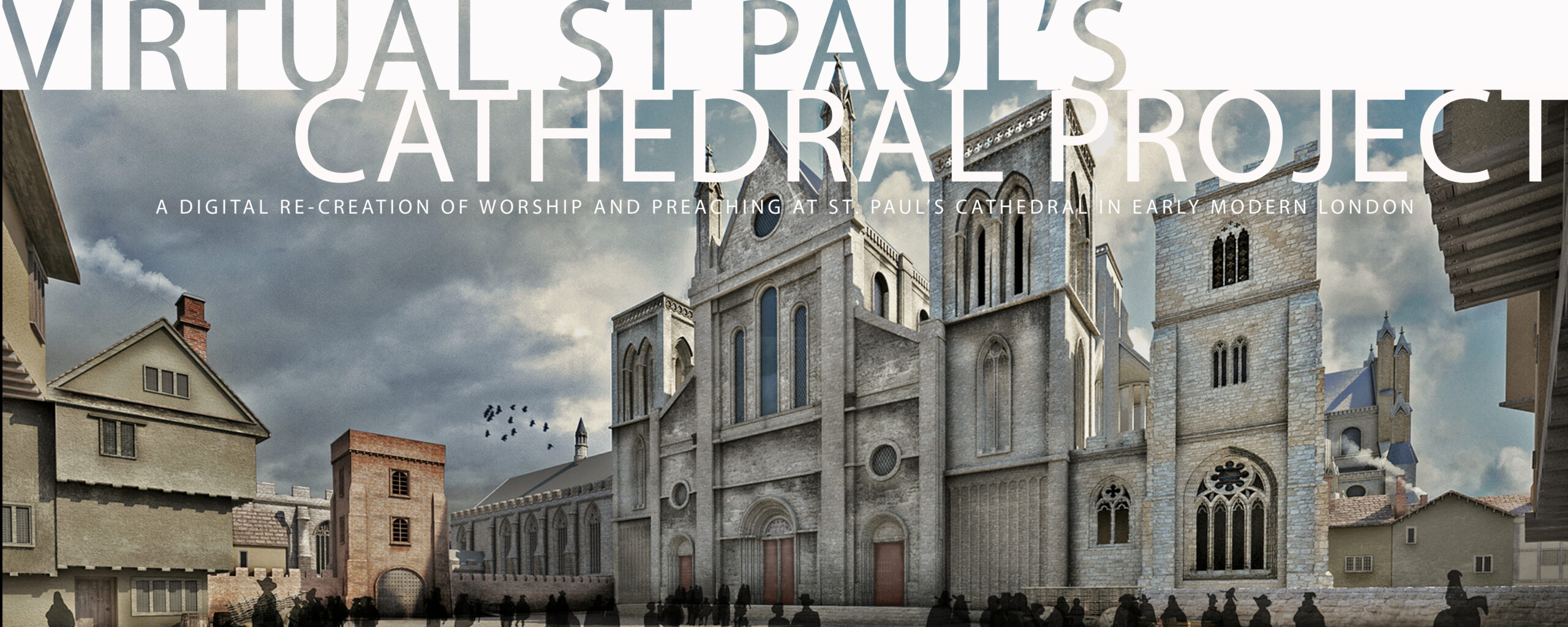

The Virtual Cathedral Project helps us understand the broader context for preaching in post-Reformation England. Arguments for a sermon-centric understanding of English religious life in this period often do not recognize the ways in which the corporate worship life of the Church of England created and defined the larger rhythms and cycles of prayer, sacrament, and biblical awareness that lay behind the individual work and spiritual lives of clergy.

Corporate Worship as Point of Conflict

One of the chief arguments of the Virtual Cathedral Project is that public worship in the early modern Church of England formed the context for the religious life of everyone. Even those who objected to worship using the Book of Common Prayer — with its set prayers, its emphasis on corporate worship, and its retention of many elements of medieval liturgical practice — found the corporate worship of the Church of England to be that which they objected to, and thus defined themselves over against.

One point for further research is the evolving sense of an appropriate alternative to worship using the Book of Common Prayer. Opponents to use of the Prayer Book proposed several kinds and forms of alternatives between adoption of the Elizabethan Prayer Book of 1559 and the Directory for Public Worship in 1644. By 1644, the directions for worship had devolved into suggestions for sources, such as Paul’s description of Jesus’ Last Supper with his disciples in I Corinthians, and directions for the order of events rather than scripts for set prayers. Earlier alternatives such as A Booke of the forme of common prayers, administration of the sacraments, &c. agreeable to Gods Worde, and the vse of the reformed churches are worthy of study because they serve as indications of the evolving nature of the opposition. Especially noteworthy is the increasing diminution of congregational participation and the emerging dominance of the Reformed preacher.

Corporate Worship as Context for Sermons, Devotional Works, and Religious Poetry

The discipline of reading the Daily Offices — with their attendant prescribed cycle of readings from the Old and New Testaments and the Book of Psalms — brought the texts of specific biblical passages to people’s awareness on a set schedule of repetition. For most people with preaching responsibilities, regardless of what text they chose to preach on for a specific occasion, their awareness of biblical passages must have been shaped by the order, and occasion, of reading the Bible according to the Prayer Book lectionaries.

Therefore, one opportunity for scholars of early modern English preaching is found in recreating the order and indentity of Biblical passages being read during Divine Service and at Holy communion in English churches.

The depth of this practice can perhaps be grasped through one of its manifestations. The Book of Psalms was read through in public worship once a month at the observance of the Daily Offices. In addition, at St Paul’s Cathedral, each of the Canons was assigned a portion of the Psalter to recite in private every day. As a result, the 30 Canons of the Cathedral knew that they, collectively, were reading the book of Psalms through once a day, in addition to the daily portion of the Psalter they read when they read the Daily Offices. This model of treating the Book of Psalms as central to their spiritual lives, in both their individual and corporate dimensions, had its most intense manifestation in the worship practice of Nicholas Ferrar’s community at Little Gidding, where the community read the Psalter through collectively every day.

Awareness of the time taken up by the performance of these rites as prescribed by the Book of Common Prayer helps us imagine the role they played in forming the larger context for the delivery of sermons. Worship according to the Book of Common Prayer occupied a significant part of the day, every day, and especially on Sundays and Holy Days. As modeled by the Cathedral Project, worship on Sundays began at 10:00 and lasted, with an hour-long sermon, as late as 1:00 in the afternoon. Worship resumed in mid-afternoon and lasted at least 45 minutes to an hour, whether or not there was an afternoon sermon.

Time in/of Worship

Recognition of the amount of time that worship lasted in English churches calls for renewed scrutiny to the question of where sermons fitted in to this routine. We know that sermons took place as part of regular morning worship on Sundays or Holy Days in the context of the Service of Holy Communion, between the recitation of the Creed and the “Prayer for the Whole State of Christ’s Church,” regardless of whether or not the service ended at that point or continued to include the celebration of Holy Communion.

According to William Harrison, the practice of sermons following Evensong in the afternoons was normative in the Church of England (“In the afternoon likewise we meet again, and, after the psalms and lessons ended, we have commonly a sermon, or at the leastwise our youth catechised by the space of an hour”). We have assumed this schedule was the practice at St Paul’s Cathedral.

This raises the possibility of research into the broader liturgical context of a particular sermon, into what, for example, were the sections of the Bible read on the particular day of a sermon’s delivery, or even a few days prior to its delivery, and whether or not they appear in the Biblical references of the sermon under consideration. It may also be able to provide dates of delivery for particular sermons by locating the sermon’s biblical references in relationship to the biblical texts that were read on a particular day.

Sermons could also take place at other times during the week, either formally as part of regular worship or as stand-alone events, perhaps in the context of a formal structure modeled on the services of the Book of Common Prayer or as, in effect, free-standing lectures. Nevertheless, to folks for whom the preaching of sermons was the most important religious activity one could engage in — rather than an important but not dominant part of a larger worship service — opposition to the formal liturgies of the Church of England was understandable.

Recognition of Prayer Book services as the normative context for preaching, however, calls for more research into how the extra-liturgical preaching of sermons — when and where it occurred — was organized and staged and how the scheduling of it fitted into the larger liturgical day. It also calls for more research into the relationship between sermons and their liturgical settings. Even if a particular sermon was preached extraliturgically — on its own rather than within a formal liturgical context — we may learn much by seeing if we can locate the biblical texts cited in the sermon in the lectionary readings for a particular day.

Divine Service and the Paul’s Cross Sermon

One of the abiding questions addressed both by the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project and the Virtual Cathedral Project is the relationship between what was happening inside the Cathedral while Paul’s Cross sermons were going on outside. By choosing a major Festival Day for our reconstruction, we happily avoided dealing with this question. But it is an important one for our understanding of the functioning of worship inside St Paul’s and the extraliturgical preaching going on outside the Cathedral.

Given the fact that the performance of the regular liturgical day, every day, was at the heart of the work of the Cathedral, one would assume that the performance of the regular liturgical day on a Sunday went on inside, even while the sermon was being preached at the Cross. To suspend it, presumably so the staff of the Cathedral could attend the sermon at Paul’s Cross, would be to abdicate that responsibility. Besides, the number of people required to maintain the regular performance of Divine Service would have been no more than the Choir plus one or a handful of the Cathedral’s cadre of resident clergy. Such a number would surely not have been missed among the crowd assembled for the sermon at Paul’s Cross.

While it is true that the Gipkin painting of a Paul’s Cross sermon in progress shows members of the Cathedral’s Choir perched precariously atop the Sermon House, the very precariousnesss of their position and the unlikelihood that they could maintain this pose for the full two-hour length of the sermon all conspire to suggest convincingly that this painting is more symbolic than literal in its depiction of events. I am definitely of the belief that during the delivery of a Paul’s Cross sermon the Choir was inside doing its job of singing the morning services of Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, and Holy Communion.

Regardless of whether a particular worship venue fitted preaching into its daily observation of the Prayer Book rites or whether it also offered extra-liturgical sermons, the clergy who preached those sermons — if they fulfilled their ordination vows — they also read the Daily Offices of Morning and Evening Prayer, as well as other services when appointed, either publicly in cathedrals or churches or in the privacy of their studies. So this means that awareness of the Bible was profoundly shaped by the system of delivery of biblical texts structured by the Lectionaries of the Book of Common Prayer.

As a result, by using the Lectionaries from the early modern Books of Common Prayer, we can know what texts from the Bible they were reading as part of their daily devotional lives. So, whether or not they make reference to those readings in their sermons or devotional writings — as Donne did in his repeated references to the relatively minor Book of Ecclesiasticus in his Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions — or draw exclusively on texts that support or illustrate the arguments they make in those sermons, we still know what was also on their minds.

Worship in Cathedrals and Parish Churches

An additional topic for research is the relationship between worship at cathedrals like St Paul’s and local parish churches. Scholarship on this topic has tended to emphasize differences, notably the absence in many, perhaps most, parish churches of organs, choirs, and the vestments associated with cathedral ceremonial. More recent scholarship has revealed, however, that collegiate churches and a significant minority of parish churches did maintain their organs and choirs, so they, presumably, followed the pattern of Cathedral choirs in performing work by Tallis, Byrd, Gibbons, and Batten.

Another source for their use was the set of four part-books published by John Day between 1560 and 1565 under the title CERTAINE notes set forth in foure and three parts to be song at the morning Communion, and euening praier, very necessarie for the Church of Christe to be frequented and vsed: & vnto them added diuers godly praiers & Psalmes in the like forme to the honor & praise of God. Not many editions of this work were published, but, then, there were not all that many congregations able to take advantage of its use.

Worship and Music

Research is also warranted into the question of what music, if any, was to be heard in parishes without instruments or choirs. Here, one must distinguish between singing the texts that constituted Prayer Book worship and singing that would have accompanied or enriched the texts of services like Morning and EVening Prayer and Holy Communion. For the daily recitation of Psalms, there were many editions of the Psalter from the Great Bible that were, according to their title-pages, The Psalter or Psalms of David: pointed as they are to be sung or said in churches, with the system of pointing enabling congregations to sing the appointed Psalms for the day to the tunes of simple chants.

One source is, of course, the many editions of Sternold and Hopkins’ Metrical Psalter. The Metrical Psalter itself is generally seen as a point of division between parish and cathedral, since historians assume that the singing of texts from the Metrical Psalter was always extra-liturgical, an add-on to Prayer Book worship rather than a support for it. The use of the Metrical Psalter outside of parish worship is well-documented, as is its use as an aid during worship services, much the way many Christian traditions today have hymnals for use at various times during worship.

Which raises the question of why the Metrical Psalter contains not only settings for metrically-regularized versions of all the Psalms, but also for other aspects of Prayer Book worship including the Canticles of Morning and Evening Prayer. If these settings were not used in worship services, the question arises, why were they included at all? And retained through the many, many editions of the Metrical Psalter printed in the early modern period? Thus providing more questions for further research.

What is well-documented is the practice of singing a Psalm before and after a sermon, described thus by William Harrison — “then proceed unto an homily or sermon, which hath a psalm before and after it” — perhaps from the Metrical Psalter. While this is often cited as a point of division between the ceremonial of cathedral and parish, it is, in fact, a sign that parish worship is being adapted from the cathedral model, since, as Clifford tells us, at St Paul’s, the sermon was preceeded and followed by an anthem.

The singing of Psalms by the assembled congregation has also been documented as part of the ceremonial surrounding sermons delivered at Paul’s Cross. Exactly how that worked is unclear, hence worthy of further study. Was there a distribution of paper copies of the music, perhaps? or the lining-out of Psalm texts by the Cathedral’s Choirmaster?

Worship and the History of Printed Books

The physical copies of Books of Common Prayer are themselves worthy of study for their written-in annotations. [1]A strong beginning to this practice is part of Daniel Swift’s discussion of the Prayer Book in his Shakespeare’s Common Prayers: The Book of Common Prayer and the Elizabethan Age (Oxford, … Continue reading. But they are also worthy of examination for the physical signs of their use. For example, frequently-used Prayer Books always reveal the sections of the book that are most frequently used, since the fingers that have touched those pages always leave their stains, visible in dark lines along the outside edges of the pages.

Who Attended Worship Services at St Paul’s Cathedral?

Also worth further study is the question of who, after all, attended worship at St Paul’s — or attended a Paul’s Cross sermon, for that matter — on Sundays when everyone in England was supposed to be attending worship in his or her parish church. There was clearly some form of accommodation; what was it and how did it work? Or, for that matter, was anyone keeping up with attendance in the parish churches? Were the rules of attendance honored more inthe breach than the observance?

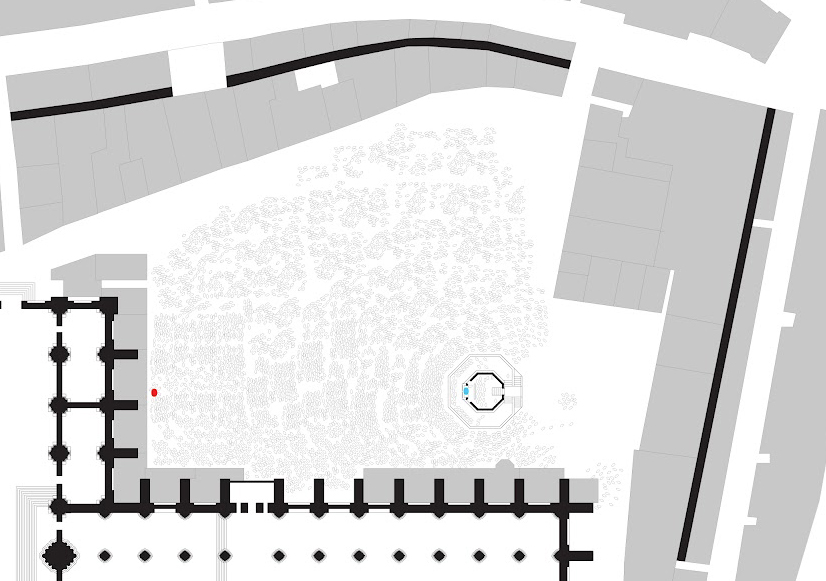

John Jewel, writing to a friend in Europe early in the reigh of Elizabeth I, estimated crowds of 5,000 or 6,000 people at Paul’s Cross sermons in which the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion was defended. Yet our modeling of crowd sizes for the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project indicate that a crowd of 5,000 people would really filled the space available for their occupancy.

Paul’s Churchyard with 5000 people. From the Paul’s Cross Visual Model, constructed by Joshua Stephens.

Estimators of crowd size today use the figure of about 4.5 to 5.0 square feet of space per person to arrive at figures for crowd size.

These numbers yield the possibility that about 6, 000 people could fit into this space. Given the fact that people were smaller physically in the early modern period, a number between 6, 000 and 7, 000 people does not seem impossible as an upper limit to the number of people who could fit into Paul’s Churchyard for a Paul’s Cross sermon.

These numbers are complicated, however, by the fact that a crowd density of one person for each 4.5 square feet yields a very high level of crowd density, perhaps an unsustainable level of crowd density, especially given the fact that the people assembled were expected to – mostly – stand in place for over two hours.

Someone at the back of this size of crowd would, I suspect, feel trapped against the north transept of the cathedral. People in crowds where the density is too great for physical and psychological comfort will either feel increasing unease — not conducive to careful listening to the preacher — or leave the space.

So we have concluded that Jewel’s numbers for the size of the crowd are exaggerations, a common result in any case, but especially for someone like Jewel who was providing these figures for a friend as part of his argument that things were going well for the restored post-Reformation Church of England. Using a modern sense of the space per person needed for a more comfortable, perhaps more sustainable, level of crowd density, we might imagine allowing each person 9 square feet, which yields space for a crowd of 3, 000.

The question still remains, however, as to who, actually, attended worship — either on a daily or weekly basis — at St Paul’s Cathedral. there are at least two sides to this question.

One is the position of Donne scholars, who want to know who was in the audience for the sermons Donne delivered inside St Paul’s, in the afternoon, at the end of Evensong, in the Choir, on Sundays and Holy Days. For us, we may find it difficult to believe that Donne would go to all the trouble it must have taken to prepare an hour-long sermon of the sort Donne preached. We must imagine that he always preached to a full house.

We know that the members of the Cathedral’s staff who were responsible for the conduct of services on that day would certainly be in attendance. That would add up to 28 or so members of the Choir, plus the organist, plus clergy (at least one) responsible for leading the service on that day, plus other members of the Resident Clergy or any visiting Canons, plus a bellringer and other staff members. So, in the mid-thirtys, as a minimum.

We also know that on certain special occasions the Lord Mayor of London and members of his entourage attended services at the Cathedral. They all had assigned seats or positions to stand when they were in attendance. But their attendance was tied to the significance of those special occasions, and thus was probably not a frequent event. Surely, also, visitors to the Cathedral on Sunday afternoons might have found their way into the Choir, even as people do today, for Evensong.

But, still, there may well have been days when Donne’s turn came up on the rota of preachers at Evensong when he was, quite literally, preaching to the Choir.

The second side to this question is that of those who participated in these services, who understood that the chief function of a cathedral in early modern England was to maintain the daily round of worship services according to the use of the Book of Common Prayer, as their “bounded duty and service.”

Cathedral clergy and musicians maintained this daily round as an end in itself, as the material embodiment of the diocese at prayer, and as a model of devotion and practice for other churches in the diocese. Worship in St Paul’s Cathedral was a manifestation and embodiment of the entire Diocese of London collectively hearing God’s Word, taking part in God’s sacraments, and offering to God the world in its brokenness for God’s healing.

So, from this perspective, while there surely were days when no one except the members of the Cathedral’s Choir and its clergy were present for one of Donne’s sermons, that probably made no difference to Donne or his colleagues, whatsoever.

“Morning Prayer in the Chapel at 8 and again in the Choir at 10”

We assert throughout this website that we are modeling full days of worship in the Cathedral on Easter Day 1624 and on the Tuesday after the First Sunday in Advent in 1645. In so doing, we are ignoring a comment made by a member of the Dean and Chapter in response to William Laud’s Visitation Articles in 1636, that a full day of worship at St Paul’s began with “Morning Prayer in the Chapel at 8 and again in the Choir at 10.”

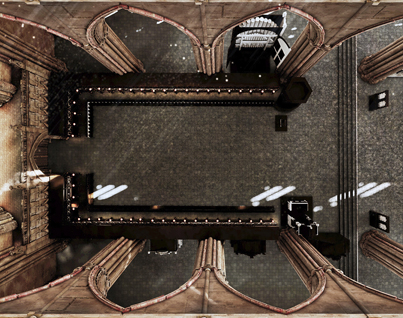

The Chapel in question was in the South Transept of the Cathedral and was known traditionally as the Morning Prayer Chapel. Here is an image of the Morning Prayer Chapel from an early stage of the Visual Model.

We had extensive conversation among the members of the Production Team and the Advisory Committee about how to respond to this comment in the Cathedral’s response to these Visitation Articles. Some folks thought that they referred to a basic, read version of Morning Prayer, to be followed by the full choral version at 10:00 in the Choir. Others thought they referred to an undetermined set of prayers read in the morning, in this Chapel, not to Divine Service as specified by the Book of Common Prayer, since Prayer Book Morning Prayer required more than a single participant.

We finally decided not to recreate a said version of Morning Prayer, but to leave resolution of the mystery of exactly what this comment meant to further research. In any case, anyone who believes that the “Morning Prayer” referred to in the Cathedral’s response to the Laudian Visitation Articles WAS the service called Morning Prayer in the Book of Common Prayer and who wants a truly complete liturgical Easter Sunday, can simply find the script for Easter Matins and read it through, providing both sides of the versicles and responses and omitting the texts of the choral anthems. The scripts for both services would otherwise be identical.

References

| ↑1 | A strong beginning to this practice is part of Daniel Swift’s discussion of the Prayer Book in his Shakespeare’s Common Prayers: The Book of Common Prayer and the Elizabethan Age (Oxford, 2013), especially pp 39-48 |

|---|