A Table of Continuities in Liturgical Practice

The Church of England experienced the Reformation in ways that fundamentally changed the life of the institution and the spiritual life of the nation. An emphasis on change, however, has a way of obscuring continuities between the medieval Church in England and the Church of England.

Among the points of continuity are the following:

1. Preservation of the Church’s organizational structure and the three basic orders of ordained ministry (Bishops, Priests, and Deacons). The system of minor orders that flourished in the Middle Ages disappeared, but the historic orders remained.

2. Preservation of the Church’s organizational structure of Dioceses and Provinces, headed by the Archbishop of Canterbury as Primate of All England and the Archbishop of York as Primate of England. The world of monasticism and religious orders disappeared, but the parochial system remained.

3. Preservation of the medieval Church’s system of Canon Law.

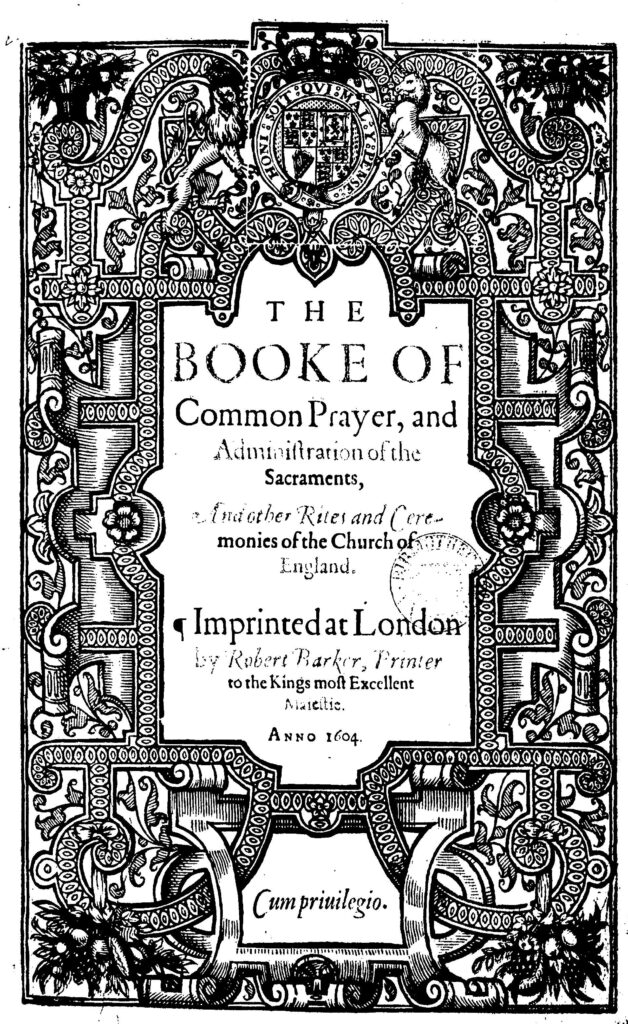

4. Continuation of formal liturgies, organized into “one use” by Thomas Cranmer in the Book of Common Prayer.

5. Continuation of the basic structure of worship for cathedrals and parish churches. The daily pattern of worship in the medieval church was Matins, Mass, and Evensong. The Church of England continued this practice on Sundays and Holy Days, adding the Great Litany to the morning rota on Sundays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

6. Continuation of specific formal rites for the traditional seven sacraments of the medieval Church. The reformed Church of England affirmed Baptism and Eucharist as the only Biblically-supported sacraments but supplied rites for the other five (Confirmation, Marriage, Ordination, Unction [in the form of rites for Visitation and Communion of the Sick], and Penance [incorporated into public rites for confession and absolution and into the rites for Ministry to the Sick]).

7. Continuation of services of the Hours (simplified from the 7-Hour structure of the Medieval monastic day to the two services of Morning and Evening Prayer). Therefore, continuation of the essentially Benedictine character of English spirituality.

8. Continuation of a formal rite for Burial of the Dead.

9. Continuation of celebrations of Saints’ Days (reduced to the saints who appear in the New Testament) and other special days like Ash Wednesday, Annunciation Day, Ascension Day, Trinity Sunday, and All Saints’ Day.

10. Continuation of the Christian Year, with its seasons of Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Easter, and Sundays after Trinity Sunday.

11. Continuation of worship in Latin (although restricted to chapels at Oxford and Cambridge Universities and other places where Latin was understood as well as English.

12. Continuation of a formal organization of programs of reading the Bible in services of public worship, as organized by the Daily Offfice and Eucaristic Lectionaries.

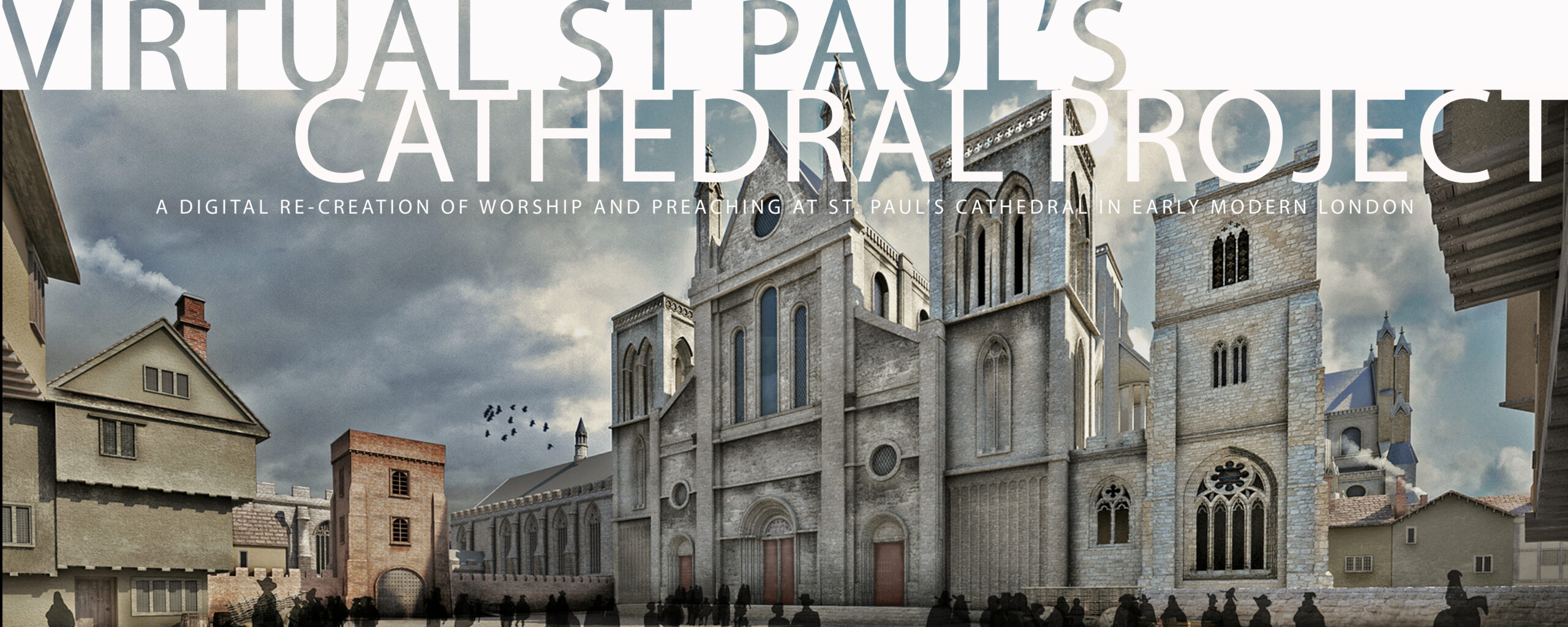

13. Continuation of use of Cathedrals as buildings and organizations outside the structure of parochial congregations.

14. Continuation of the use of formal choirs and sung services at Cathedrals and Collegiate churches like Westminster Abbey.

15. Continuation of the use of distinctive vestments for clergy, including copes (in Cathedrals), surplices, tippets, and clerical caps (use of chasubles, although authorized by the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion, did go out of fashion).

16. Continuation of the use of names of the Saints who did not survive the Reformers’ pruning of the Roman calendar of Saints to include only New Testament figures. For example, the name of St Hilary of Poitiers, whose feast day is January 13th, is still used to name court and academic terms that include St Hilary’s feast day. Also, in Shakespeare’s Henry V, when King Henry declares that the day of the Battle of Agincourt is taking place on St Crispin’s Day, his audience would have known that St Crispin’s feast day was October 25th.