This being done, we proceed unto the communion, if any communicants be to receive the Eucharist; if not, we read the Decalogue, Epistle, and Gospel, with the Nicene Creed (of some in derision called the “dry communion”), and then proceed unto an homily or sermon, which hath a psalm before and after it, and finally unto the baptism of such infants as on every Sabbath day (if occasion so require) are brought unto the churches; and thus is the forenoon bestowed. — William Harrison, A Description of England (1577)

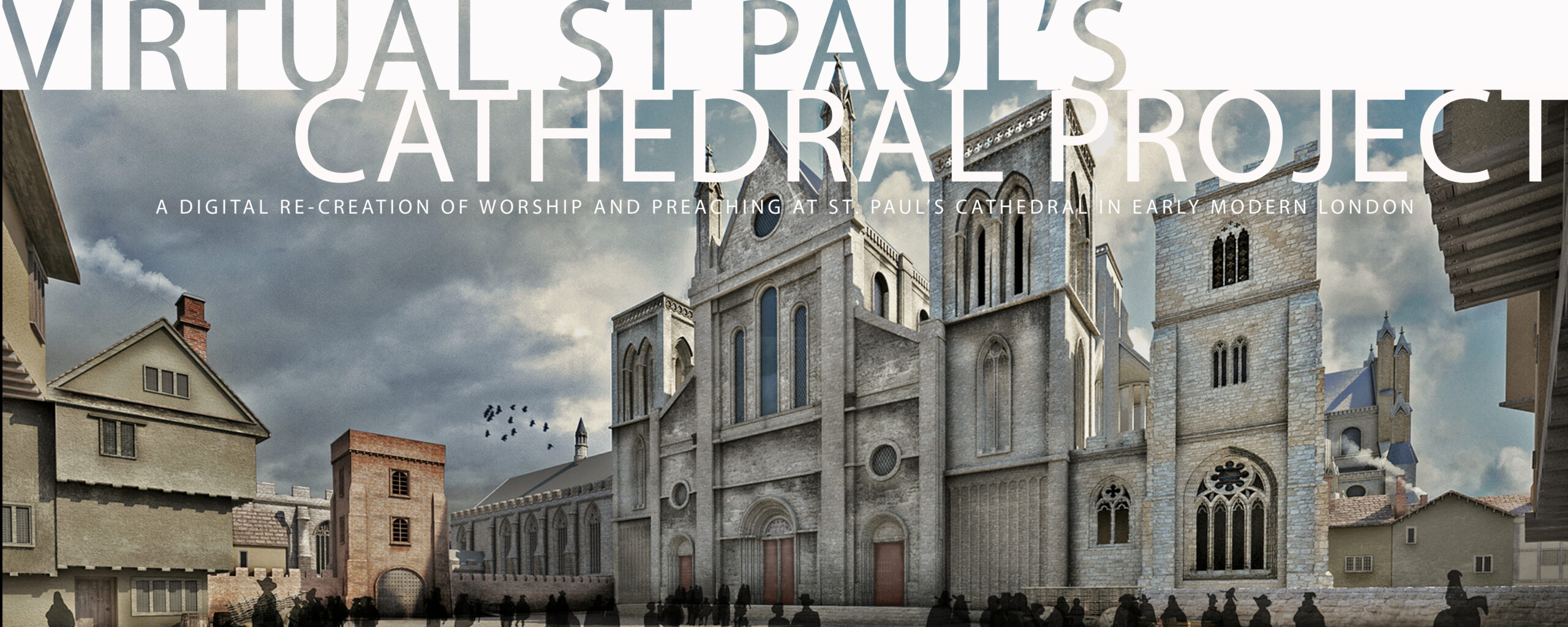

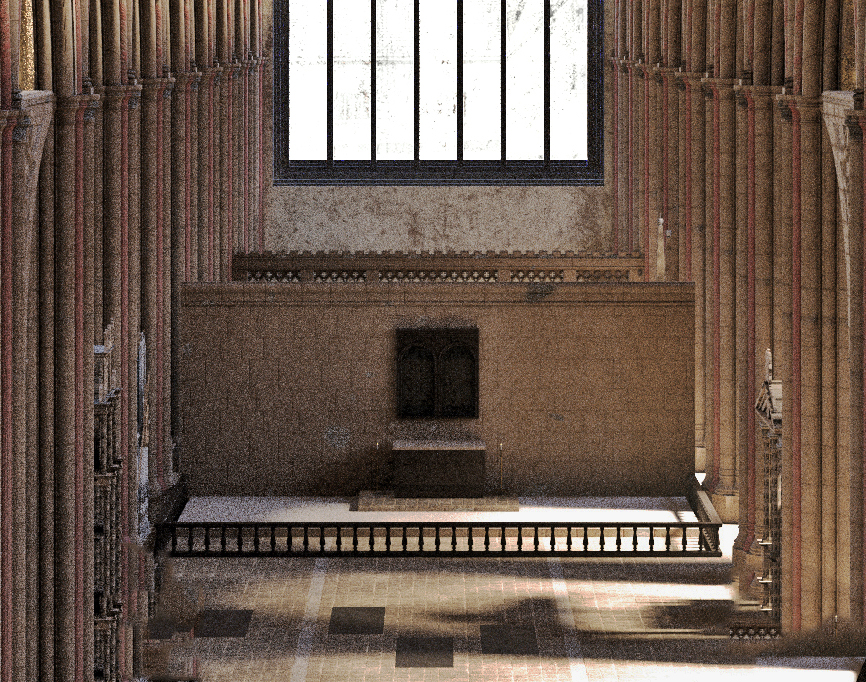

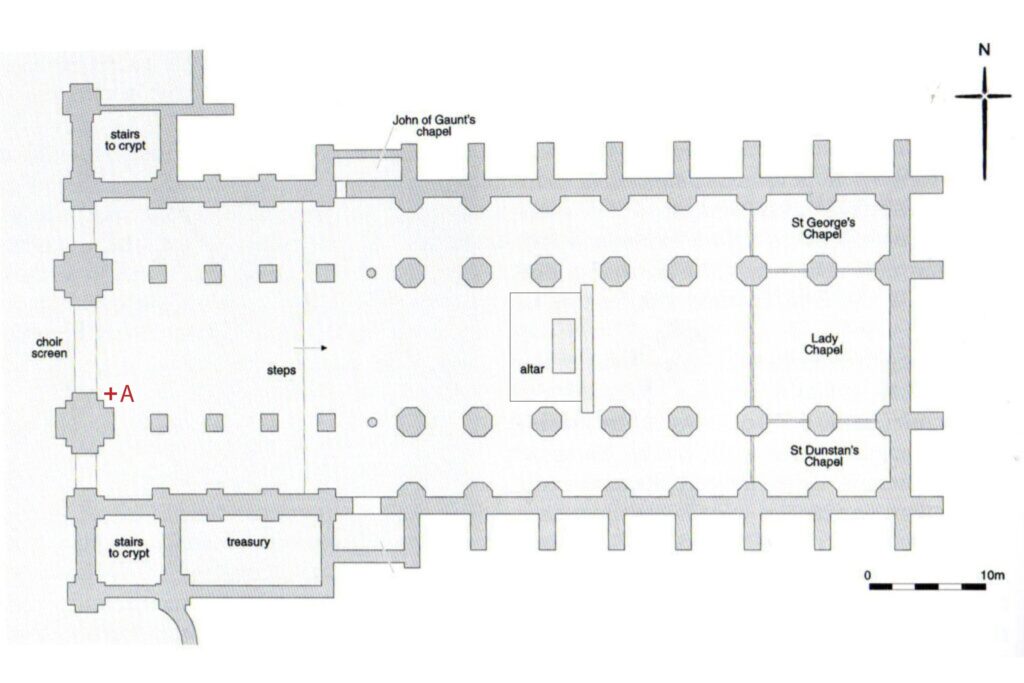

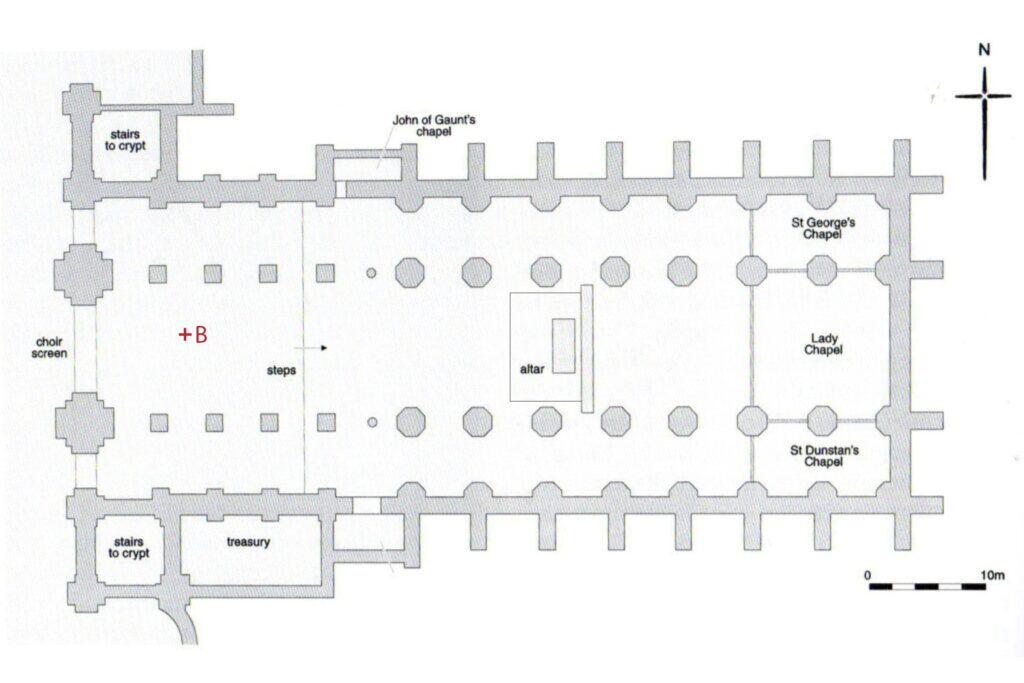

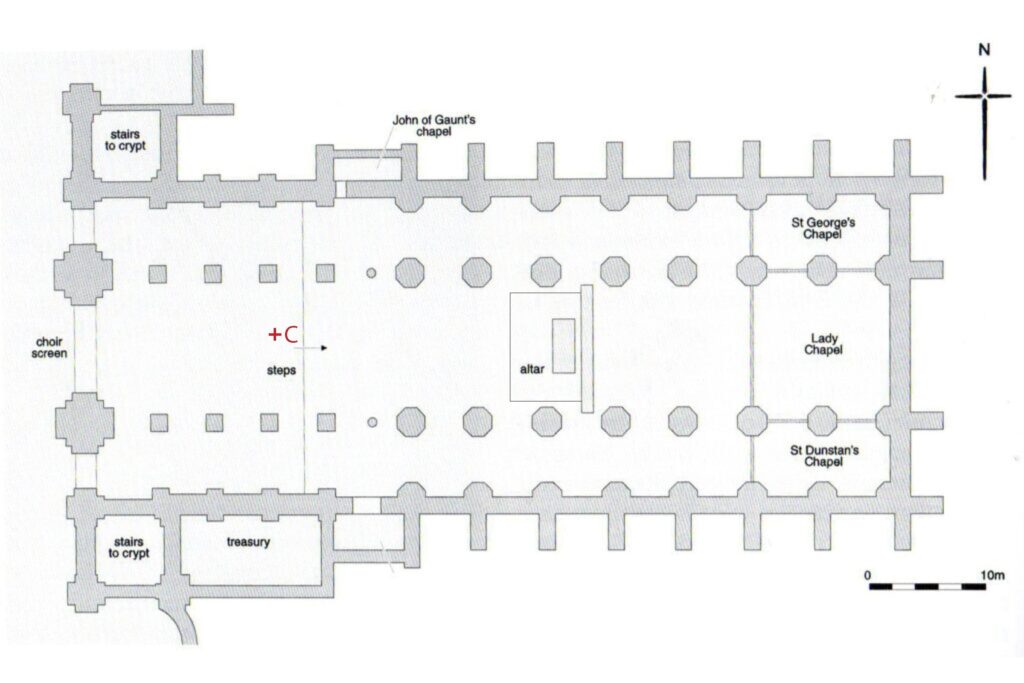

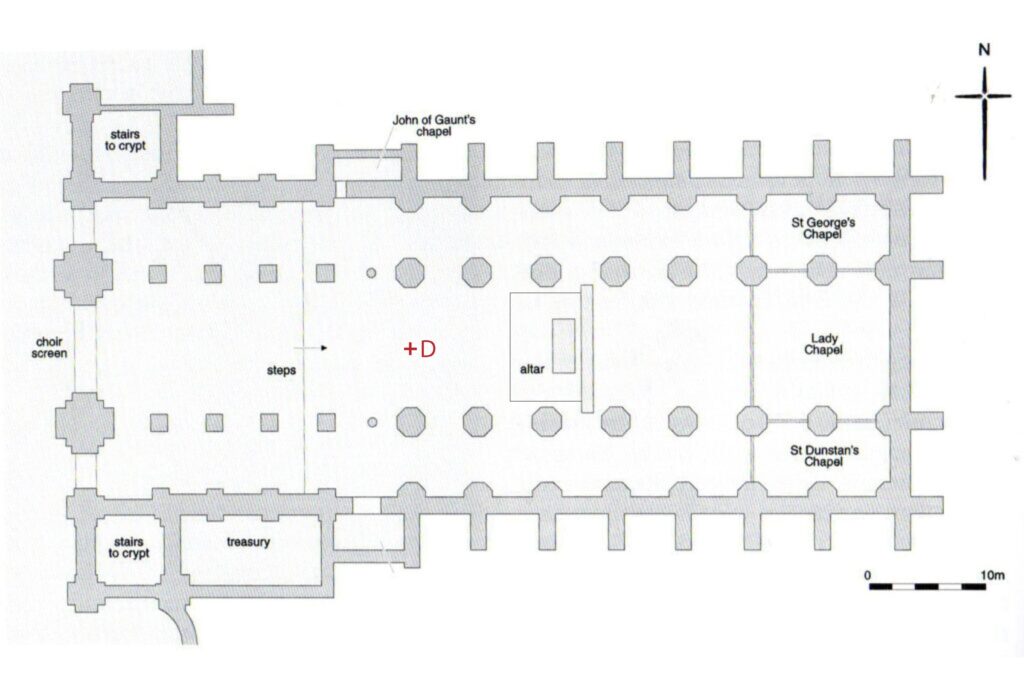

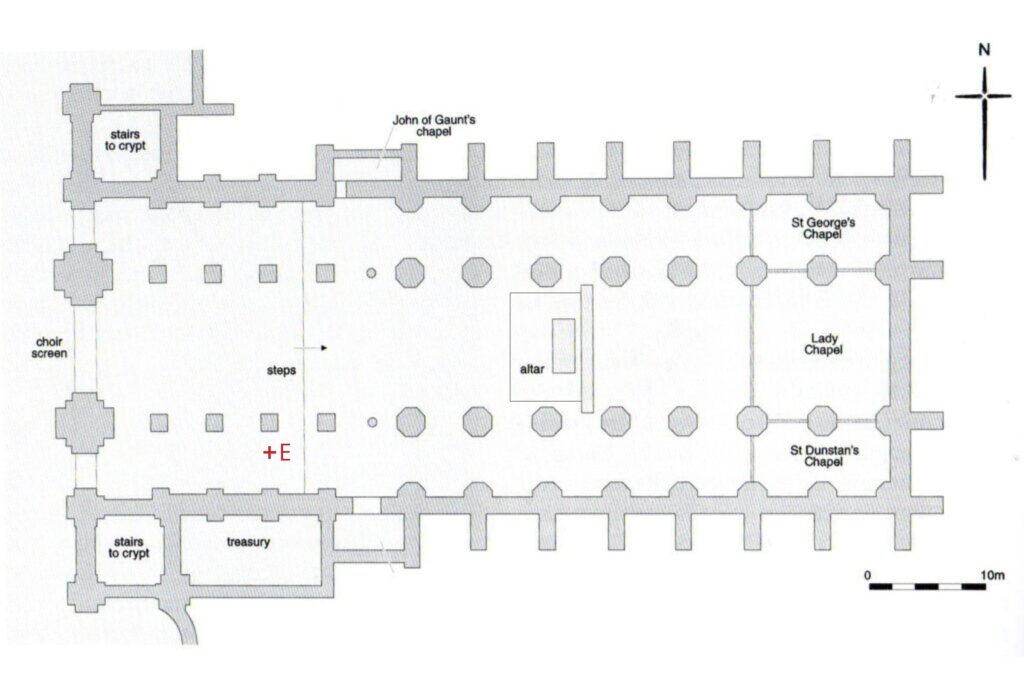

This page of the Cathedral Project website allows the user to experience the rite of Holy Communion from each of the five different Listening Positions we have chosen as representative of the acoustic experience of worship in the Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral during Donne’s tenure as Dean.

At the point in this service when members of the congregation are to come forward to receive the bread and wine of Holy Communion, the Listening Position shifts to Position F, just before the Altar. This shift seems appropriate as an experience for every user of this site, since according to the Canons of the Church of England every member of the Church of England was required to receive the elements of Communion on Easter Sunday.

At the bottom of this page is an annotated script of this service. To experience all the services from a single Listening Position, go to the Locations page.

Listen from the Dean’s Stall

From Mid-Choir

From the Pulpit

From Midway between the Stalls and the Altar

From the South Aisle

The Annotated Script

Guide to the color coding: The words in black are the words spoken. The words in red are the directions printed in the Book of Common Prayer for the conduct of the service, hence the name rubrics for these directions. The words in blue are the annotations.

THE ORDRE

FOR THE

ADMINISTRACION OF THE LORDES SUPPER,

OR

HOLY COMMUNION.

This is the script for Holy Communion on Easter Day 1624 used to make recordings of this service found elsewhere on this website. Where there are choices to be made in the Rite, only the choices made for these recordings are included. To see the full text of the Rite, consult the Book of Common Prayer in its 1550 or 1604 editions. The easiest way to do this is to consult the edition of the 1559 Prayer Book edited by John E. Booty and published by the University Press of Virginia for the Folger Shakespeare Library, either in the first edition of 1976 or the second edition, with a new Foreword by Judith Maltby, published in 2005.

The Rite for the Service of Holy Communion in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer is entitled “The Supper of the Lorde and holy Communion, commonly called the Masse.” The title “THE ORDER FOR THE ADMINISTRACION OF THE LORDES SUPPER, OR HOLYE COMMUNION” was adopted for this rite in the Prayer Book of 1552 and remained so through the Prayer Books of 1559, 1604, and 1662. This name change reflects Cranmer’s determination both to distinguish what was happening in the Prayer Book’s Communion Rite from what was happening in the Medieval Church’s Mass (so as to avoid adoration of the consecrated bread and wine), while at the same time to affirm that the Rite was a Rite of Communion, the recognition of and the building up of the gathered community of the Church as “very members incorporate in [Christ’s] mystical body, which is the blessed company of all faithful people.”

________________________________________

Cranmer’s Rite of Holy Communion is in a kind of dialogue with the Medieval Mass. The opening prayers below make public and corporate the private preparatory rite of the celebrant and other clergy in the Latin rite.

Priest

OUR Father, whiche arte in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kyngdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heaven. Geve us this day our dayly breade. And forgeve us our trespasses, as we forgeve them that trespasse against us. And lead us not into temptacion. But deliver us from evil. Amene.

ALMIGHTY God, unto whom al hartes be open, al desires knowe, and from whom no secretes are hyd: clense the thoughtes of our hartes by the inspiracion of thy holy spirite, that we may perfectly love the, and worthily magnify thy holy name, through Christe our Lorde.

The people shal aunswere.

Amen.

What follows in the Latin rite is the Kyrie (in Greek, “Kyrie, eleison/ Christe, eleison/Kyrie, eleison; in English, “Lord, have mercy upon us; Christ, have mercy upon us; Lord, have mercy upon us”). In Cranmer’s version, the phrase becomes “Lord, have mercy upon us, and incline our hearts to keep this law,” and is used as a response to a recitation of the Ten commandments.

Then shal the Priest rehearse distinctly at the .x. Commaundementes, and the people knelyng, shal after every Commaundemente aske Goddes mercye for theyr transgressyon of the same, after thys sorte.

Kyrie (responses to the Commandments) by Thomas Morley

Minister. God spake these wordes, and saide, I am the Lord thy God, Thou shalt have none other Goddes but me.

People. Lorde have mercye upon us, and encline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

Minister. Thou shalt not make to thy self any graven ymage, nor the likenes of any thyng that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneth, or in the water under the earth. Thou shalt not bow doune to them, nor worshyppe the, for I the Lord thy God am a gelous God, and visite the synne of the fathers uppon the children, unto the thyrde and iiii. generacyon of them that hate me, and shew rnercie unto thousandes in theim that love me, and keepe my commaundementes.

People. Lorde have mercye upon us, and encline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

Minister. Thou shalt not take the name of the Lorde thy God in vaine, for the Lorde wil not holde hym giltlesse that taketh his name in vaine.

People. Lorde have mercie upon us, and encline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

Minister.Remembrethat thou kepe holy the Sabboth daie: .six. dayes shalt thou laboure, and doe all that thou haste to do, but the seventh day is the Sabboth of the lorde thy god. In it thou shalt do no maner of worke, thou and thy sonne and thy daughter, thy man servaunt, and thy mayd servaunt, thy Catel, and the straunger that is within thy gates: For in six daies the Lord made heaven and earth, the Sea and all that in them is, and reasted the seventh daye. Wherefore the Lorde blessed the seventh daye and halowed it.

People. Lorde have mercy upon us, and encline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

Minister. Honour thy father and thy mother, that thy daies may be long in the lande which the Lord thy God geveth the.

People. Lorde have mercy upon us, and encline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

The Minister. Thou shalt not do murther.

People. Lorde have mercy uponus, and encline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

Minister. Thou shalt not committe adultery.

People. Lorde have mercy upon us, and encline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

Minister. Thou shalt not steale.

People. Lorde have mercy upon us, and incline our hartes to kepe this lawe.

Minister. Thou shalte not beare false wytnesse agaynste thy neyghboure.

People. Lorde have mercy upon us, and encline our hartes to kepethis lawe.

Minister. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbours house, Thou shalt not covet thy neighbours wife, nor his servaunt, nor hismaide, nor his oxe, nor his asse, nor any thing that is his.

People. Lord have mercy upon us, and write al these thy lawes in our hartes we beseche the.

In the Latin rite, the Kyrie is followed by a song of praise and thanksgiving to God, called the Gloria in excelsis; In Cranmer’s version, the Gloria is shifted to the end of the Communion Rite, to serve as a culmination of the congregation’s journey from hearing God’s Word proclaimed in Bible readings and in preaching, through prayers of intercession, confession, and absolution, to participation in the offering, blessing, breaking, and receiving of the consecrated bread and wine. Here, the Gloria’s words of praise and thanksgiving (“We praise thee, we bless thee, we worship thee, we glorify thee, we give thanks to thee for thy great glory”) take their meaning directly from the congregation’s participation in the Holy Communion.

Instead of the Gloria after the Kyrie, Cranmer moves on to the Collect for the Day, the Collect for the Monarch, and the readings appointed for the day from the New Testament’s Epistles and Gospels. There are two kinds of texts used in celebrations of Holy Communion — the Propers and the Ordinary. The Propers are texts — especially the Collect for the Day and the appointed readings from the Bible that vary from Sunday to Sunday or from Holy Day to Holy Day — that are the proper texts for use on those specific days. The Ordinary parts of the service are all the parts — like the Prayer for the Whole State of Christ’s Church, the recitation of the Nicene Creed, and the central texts of the Prayer of Consecration — that do not vary from service to service. Hence, they are the texts that are ordinarily used on occasions like this.

¶ Then shall folowe the Collect of the day with one of these two Collectes folawyng for the King, the Priest standyng up and saying.

The Collect for the Day is one of the Proper parts of this service, the Collect specified by the Eucharistic Lectionary of the early Prayer Books for use on Easter Sunday. Included in this list of required usages for Easter Sunday are the readings for the Epistle and Gospel.

Priest.

Let us praye

ALMIGHTIE God, whiche through thy onely begotten sonne Jesus Christ hast overcome death, and opened unto us the gate of everlasting life; we humbly beseche thee, that, as by thy speciall grace, preventing us, thou doest put in our mindes good desires, so by thy continuall help we may bring the same to good effect; through Jesus Christ our Lorde who lyveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end.

The people shal aunswere.

Amen.

ALMIGHTY God, whose kyngdom is everlasting, and power infinite, have mercy upon the whole congregacion, and so rule the heart of thy chose servant James our King and governoure that he (knowing whose minister he is) may above all thinges, seke thy honoure and glorye: and that we his subjectes, (dulyconsidering whose aucthority he hath) may faithfully serve, honour, and humblye obey him in the and for the, according to thy blessed worde, and ordinance, through Jesus Christ our Lord, who with the and the holye ghost, lyveth and reygneth ever one God, worlde without ende.

The people shal aunswere.

Amen.

Immediately after the Collectes, the Priest shall reade the Epystle beginning thus.

EPISTLE AND GOSPEL TO BE SUNG IF THEY ARE AT MATTINS

The Epystle written in the Third Chapiter of Colossians.

If ye then be risen with Christ, seek those things which are above, where Christ sitteth on the right hand of God.

Set your affection on things above, not on things on the earth.

For ye are dead, and your life is hid with Christ in God.

When Christ, who is our life, shall appear, then shall ye also appear with him in glory.

Mortify therefore your members which are upon the earth; fornication, uncleanness, inordinate affection, evil concupiscence, and covetousness, which is idolatry:

For which things’ sake the wrath of God cometh on the children of disobedience:

In the which ye also walked some time, when ye lived in them.

And the Epystie ended, he shal say the Gospel, beginninge thus.

The Gospell wrytten in the twentieth Chapiter of John.

The first day of the week cometh Mary Magdalene early, when it was yet dark, unto the sepulchre, and seeth the stone taken away from the sepulchre.

2 Then she runneth, and cometh to Simon Peter, and to the other disciple, whom Jesus loved, and saith unto them, They have taken away the Lord out of the sepulchre, and we know not where they have laid him.

3 Peter therefore went forth, and that other disciple, and came to the sepulchre.

4 So they ran both together: and the other disciple did outrun Peter, and came first to the sepulchre.

5 And he stooping down, and looking in, saw the linen clothes lying; yet went he not in.

6 Then cometh Simon Peter following him, and went into the sepulchre, and seeth the linen clothes lie,

7 And the napkin, that was about his head, not lying with the linen clothes, but wrapped together in a place by itself.

8 Then went in also that other disciple, which came first to the sepulchre, and he saw, and believed.

9 For as yet they knew not the scripture, that he must rise again from the dead.

10 Then the disciples went away again unto their own home.

And the Epistle and Gospel being ended, shalbe said the Crede.

The Nicene Creed is specified for use in the Rite of Holy Communion, while the Apostles Creed is specified for use at Morning and Evening Prayer, except, as we have seen, for Easter Sunday, when the Creed of St Athanasius is specified for use at Morning Prayer.

Creed by Thomas Morley

I BELEVE in one God, the father almighty maker of heaven and earthe, and of all thynges visible and invisible: And in one Lorde Jesu Christe, the onely begotten sonne of GOD, begotten of his father before al worldes, god of God, lyghte of lyghte, verye God of verye God, gotten, not made, beynge of one substance wyth the father, by whome all thinges were made, who for us men, and for oursalvacion came doune from heaven, and was incarnate bythe holy Ghoste, of the Virgine Mary, and was made man, and was crucified also for us, under poncius Pilate. He suffered and was buried, and the thyrde dayhe rose againe accordinge to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven, and sitteth at the right hande of the father. And he shal come againe with glory, to judge both the quicke and the deade, whose Kyngdome shall have none ende. And I beleve in the holye Ghoste, The Lorde and gever of life, who procedeth from the father and the sonne, who with the father and the sonne together is worshipped and glorified who spake by the Prophetes. And I beleve one catholicke and Apostolicke Churche. I acknowledge one Baptisme, for the remission of synnes. And I loke for the resurreccion of the dead : and the lyfe of the worlde to come.

The people shal aunswere.

Amen.

After the Creede, if there be no Sermon, shall follow one of the Homilies alreadie set forth, or heerafter to be set foorth by common authoritie.

The sermon delivered on behalf of Bishop Andrewes by David Crystal is the sermon that Bishop Andrewes had prepared to deliver on Easter Sunday 1624 but was unable to do so because he was ill on that day. We do not know what prayer Bishop Andrewes prayed at this particular moment in the service. We do know he must have prayed a prayer and also the Lord’s Prayer as prefatory to his announcing his text and commencing with his sermon, because preachers were instructed to do this by the Canons of the day. We have provided the Bishop of Winchester with a prayer here, as we did for Dean Donne at his sermon for Evensong on Easter, by adapting the directions given preachers as to what the content of their prayer before sermon should include.

Sermon by Lancelot Andrewes

Let us pray for Christ’s Holy Catholic Church, the whole Congregation of Christian people dispersed throughout the whole world, and especially for the Churches of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Let us pray most especially for the King’s most excellent Maiestie our Soveraigne Lord James, King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland, Defendour of the Faith, and Supreme Gouernour in these Realmes, and all other his Dominions and Countreyes, over all persones, in all causes, aswell Ecclesiasticall as Temporal. Let us pray also for our noble prince Charles; Frederick Prince Electour Palatine, and the Lady Elizabeth his wife. Let us pray also for the Ministers of God’s holy word and sacramants, aswell Archbishops and Bishops, as other Pastours and Curates. Let us pray also for the King’s most honourable Counsell, and for all the Nobility and Magistrates of this Realme, that all and every of these in their severall Calling, may serve truly and painefully, to the glory of God, and the edifying and well governing of his people, remembering the account that they must make. Also, Let us pray for the whole Commons of this Realme, that they may live in true Faith and Feare of God; in humble obedience to the King, and Brotherly charity one to another. Finally, let us praise God for all those which are departed out of this life in the Faith of Christ, and pray unto god that wee may have grace to direct our lives after their good example: that this life ended, wee may bee made partakers with them of the glorious Resurrection in the life Everlasting., through the merits of Christ Jesu our Savior, who liveth and reigneth with thee in the unity of the Holy spirit, one God, world without end.

The people shal aunswere.

AMEN.

OUR Father, whiche arte in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kyngdom come. Thy will be done in earth as it is in heaven. Geve us this day our dayly breade. And forgeve us our trespasses, as we forgeve them that trespasse against us. And lead us not into temptacion. But deliver us from evil.

The people shal aunswere.

AMEN.

THE SERMON

Priest

A Reading from the Epistle to the Hebrews, the twelfth chapter, beginning at the 20th verse.

Now the God of peace, that brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus Christ, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant,

Make you perfect in every good work to do his will, working in you that which is well pleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ; to whom be glory for ever and ever. Amen.

Here endeth the reading.

These words, ‘Who hath brought Christ again from the dead,’ make this a text proper for this day; for as this day was Christ ‘brought again’ from thence.

And these words, ‘the blood of the everlasting testament,’ make it as proper every way for a Communion; for there, at a Communion, we are made to drink of that blood. Put these together, 1. the bringing of Christ from the dead, 2. and ‘the blood of the Testament,’ and they will serve well for a text at a Communion on Easter-day.

For the nature, it is a benediction. The use the Church doth make of it and such other like, is to pronounce them over the congregation by way of blessing. For not only the power to pray, to preach, to make and to give the Sacrament; but the power also to bless you that are God’s people, is annexed and is a branch of ours, of the Priest’s office. You may plainly read the power committed, the act enjoined, and the very form of words prescribed, all in the sixth of Numbers. There God saith, ‘Thus shall you bless the people,’ that is, do it, you shall, and thus you shall do it, in hæc verba. Neither was this act Levitical, or then first taken up, it was long before: ‘while Levi was yet in the loins of Abraham,’ even then it was a part of Melchisedek’s priesthood, and if the bread and wine were no more but a refreshing, the only part that we read of, to say Benedictus over Abraham, as great a patriarch as he was. There is nothing else mentioned to shew he was a Priest, but that.

This blessing they used first and last, but rather last. For lightly then, the people were all together. They be not so as first, but only a few then. And here, you see, the Apostle makes it his farewell. With this he shuts up his Epistle, and with some other such, all the rest. And that, by Christ’s example. The last thing that Christ did in this world, was: He lift up His hands ‘to bless His disciples,’ and so went away to heaven. And so you shall find it was the manner in the Primitive Church: at the end of the Liturgy, ever to dismiss the assembly with a blessing. Which blessing they were then so conceited of, they would not offer to stir, not a man of them, till bowing down their heads they had the blessing pronounced over them. As if some great matter had lain in the missing of it; as if they had been of Jacob’s mind, Non dimittam Te nisi benedixeris mihi: they would neither let the priest depart, nor depart themselves, till they had their blessing with them; such a virtue they held in it. The blessing pronounced, they had then leave to go, with λαοiς αφες, in the Greek; missa est fidelibus, in the Latin Church; and none went away before.

An evil custom hath prevailed with our people; away they go without blessing, without leave, without care of either. Mark if they run not out before any blessing, as if it were not worth the taking with them.

I marvel how they will be ‘inheritors of the blessing,’ that seem to set so little by it. If they mean to hear ‘Come ye blessed,’ they should methinks love it better than by their running from it they seem to do.

This would be amended. We are herein departed from the Primitive Christians, with whom it was in more regard. Sure there is more in the neglect of it than we are aware of.

This blessing could not be delivered in better terms than in those that came from the Apostles themselves, which accordingly have been sought up here and there in their writings, and by the Church sorted to several days which they seemed best to agree with. As this here, having Easter-day in it, was made an Easter-day benediction. For the special mention in it of Christ ‘brought again from the dead,’ doth in a manner appropriate it to this feast. Utter it but thus: ‘The God of peace Who did now, as upon this day, bring again Christ from the dead’–do but utter it thus, and it will appear most plainly how well they suit, the time, and the text.

For the sum. It is no more in effect but shortly this. That God would so bless them and us, as to make us fit for, and perfect in, all good works. A good wish at any time. But why at this time specially, upon mention of Christ’s rising, he should wish it, is not seen at first. Yet there is some matter in it, that at Christ’s rising He doth not wish our faith increased, or our hope strengthened, or any other grace or virtue revived; but only, that good works might be perfected in us, and we in them. Surely, this sorting them thus together seems to imply as if Christ’s resurrection had some more peculiar interest in good works, as indeed it hath. And there hath ever been, and still are, more of them done now at this time, than at any other time of the year.

A general reason may be given. That what time Christ doth for us some principal great work, as at all the feasts He doth some, and now at this time sensibly, we to take occasion by it at that time to do somewhat more than ordinary in memory and honour of it. More particularly, some such as may in some sort suit with and resemble the act of Christ then done. As it might be, when Christ died, sin to die in us; when Christ rose again, good works to rise together with Him. Christ’s passion, to be sin’s passion; Christ’s resurrection, good work’s resurrection. Good-Friday is for sin, Easter for good works. Good-Friday to bring sin to death, Easter to bring good works from the dead. And we that were dead before to good works, by occasion of this to revive again to the doing of them; and not as the manner is with us, sin to have an Easter, to rise and live again, and good works to be crucified, lie dead and have no resurrection.

For the partition. Two verses there are, and two parts accordingly. 1. the premises, and 2. the sequel. The premises are God, and the sequel good works. The former verse is nothing but God, with His style or addition; ‘The God of peace Which brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant. The latter is all for good works, ‘Make you perfect in every good work to do his will, working in you that which is well pleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ.” We may consider them thus. Of the two, 1. one a thing done for us, in the former verse; 2. the other, a thing to be done by us, in the latter verse. The bringing back Christ, the benefit done us by God; the applying good works, our duty to be done to Him for it.

The thing done is an act, that is, a bringing back. Which act is but one, but implieth another precedent necessarily, For αναγαγων, which is a ‘bringing back,’ implieth αγαγων, which is a ‘bringing thither.’

To this act there is a concurrence of two agents. 1. One, the party that brought; 2. the other, the party that is brought. The party that brought is God, under the name or title of ‘the God of peace.’ The party that was brought is Christ, set forth here under the metaphor of a Shepherd, `the great Shepherd of the sheep.’

‘The God of peace’ did bring again this ‘Shepherd;’ from whence and how? 3. From whence? ‘From the dead.’ Then among the dead He was the first. First, brought thither; 4. how from thence? by what means? ‘By the blood of a Testament everlasting.’ All which is nothing else but the resurrection of Christ extended at large through all these points.

The thing to be done, that God would so bless them as ‘to make them,’ 1. First, ‘fit to do;’ 2. and then ‘to do good works.’ 1.’Fit to do,’ in the word καταρτίσαί ‘To do.’ Wherein we consider two things; 1. the doing. To which doing there is a concurrence of two agents. 1. Είς το ποίήσαί νμάς, what we to do; 2. and πoiων εν ύμίν, what He to do. 2. And then the work itself expressed in two words, 1. θελήμα, and 2.ενάρεστον — θελήμα, that is, ‘His Will;’ ενάρεστον , ‘that which is well pleasing’ in His sight. These two be holden for two degrees; and the latter of the twain to have the more in it.

And last of all, the sequel. Where is to be shewed, how these two hang together and follow one upon the other. First, the ‘God of peace,’ and the bringing of Christ from death. Then, how the bringing of Christ from death concerns our bringing forth good works. Which being shewed, what this feast of Easter hath to do with good works will fall in of itself. That with Christ now rising they also should now rise–they are thought as good as dead–that there may be a resurrection of them as Christ’s resurrection.

‘The God of peace, which brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant.” Here is a long process, What needs all this setting out His style at length? Why goes He not to the point roundly? And seeing good works’-doing is His errand, why saith He not shortly, God make you given to good works! and no more ado? but tells us a long tale of Shepherds and Testaments, and I wot not what, one would think to small purpose? But sure to purpose it is, the Holy Ghost useth no waste words, nor ever speaks but to the point we may be sure.

Let us see, and begin with His first title,’the God of peace.’ God’s titles be divers, as be His acts; and His acts are, as His properties be they proceed from. And lightly, the title is taken from the property which best fits the act it produceth. As when God proceedeth to punish, He is called the ‘righteous God;’ when to show favour, ‘the God of mercy,’ when to do some great work, ‘the God of power.’ Now then this seems not so proper; should it not rather have been, ‘the God of power Which brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant.” To bring again from death seems rather an act of power than of peace. One would think so. But being well looked into, it will be found to belong rather to peace. No power of His will be set on working, will ever bring again from the death, unless He be first pacified and made the Lord of peace. Of His power there is no question; of His peace there may be some. I shall tell you why. For all the Old Testament through you shall observe God’s great title is ‘the Lord of Hosts,’ which in the New you shall never read; but ever since He rose from the dead it is, instead of it, ‘the God of peace.’ To the Romans, Philippians, Thessalonians, Galatians, Colossians, Corinthians, and now here to the Hebrews; and still, ‘the God of peace.’ It is not amiss for us, this change. For if the Lord of Hosts come to be at peace with us, His hosts shall be all for us, which were against us, while it was no peace. So as make but God ‘the God of peace,’ and more needs not. For His peace will command His power straight.

When His hosts were so about Him, it seemed hostility; how came He then to lay away that title of ‘the Lord of Hosts,’ to become Deus pacis? That did He by thus doing; He brought again one from the dead, and that bringing brought peace, and made this change stylo novo, ‘the God of peace.’

This brings us to the other, the second party; He is not named till all be done, and then He is in the end of the verse,’our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ.’ But at first He is brought in as a Shepherd. Think never the meaner of Him for that. Moses and David, the founders of the monarchy of the Jews; Cyrus and Romulus, the founders, one of the Persian, the other of the Roman monarchy, were taken all from the sheepfolds. The heathen poet calls the great ruler of the Grecian monarchy but ποίμενα λαων, that is, the ‘Shepherd of the people.’ Christ gives it to Himself and God doth not disdain it in the eightieth Psalm. And the name, howsoever it falls to us of the Clergy now, ab initio non fuit sic. Secular men, Joseph, Joshua, and David, were first so termed, and are more often so termed in the Bible than we.

The term of ‘Shepherd’ is well chosen as referring to ‘the God of peace.’ Peace is best for shepherds and for sheep. They love peace: then they are safe, then they feed quietly. Yet not so but that shepherds have ventured far to rescue the sheep from the bear and from the lion, as did King David, and as the Son of David here That ventured farther than any, Who is brought in here in sanguine, ‘bleeding,’ howsoever it comes.

But this title was not so much for God as for us–Pastorem ovium; and in ovium are we, there we come in, we hold by that word. For so there is a mutual and reciprocal relation between Him and us; that we thereby may be assured by this very term relative, whither, and whensoever He was brought, all He did or suffered, it was not for Himself. For then an absolute name of His own would have been put. All for this correlative, for ovium, that is, for us. He is no ways considered in all this, as absolutely put or severed from us, His flock, but still with reference and relation unto us.

But because others enter common in this and other His names with Him, He bears it with a difference; Pastor Magnus, the great Shepherd. Not, as Diphilus said to Pompeuis Magnus, Nostrâ miseriâ magnus es, ‘great by making others little,’ but misericordiâ suâ magnus, ‘by making Himself little to make us great.’

The gradual points of His greatness, in respect of others, are these. Great first, for totum is parte majus; greater is He That feeds the whole, than they that but certain parcels of the flock. All else feed but pieces; so they be but petty shepherds to Him. But He, the whole, main entire flock; He and none but He. So He ‘the great Shepherd’ of the great flock.

Again, greater is He That owns the sheep He feeds, than they that feed the sheep they own not. All others feed His sheep; none can say, pasce oves Meas. His they be; and reason. For ‘He made them,’ they be ‘the sheep of His hands;’ He feeds them, so the sheep of His hands, and of ‘His pasture’ both.

But this is not the greatness here meant. But Ecce quantam charitatem, ‘see the great love’ to His sheep! Others sell and kill theirs. He is so far from selling or killing as He, this Shepherd, was sold and slain for them, though they were His own. Paid for them, bought them again, and then ‘He brought them again.’ It may be there were others had ventured their lives, but not lost them and so lost them as He did. Which makes Him not only great, but primae magnitudinis, that is, simply the greatest that ever was.

Of which greatness, two great proofs there are in the two words: 1. Sanguis, and 2. Testamentum. Sanguis, a great price; Testamentum, a great legacy. Sanguis, what He suffered; Testamentum, what He did for them.

The next word is in sanguine, a Shepherd ‘in His blood.’ So this Shepherd sweat blood, ere He could bring them back. It was no easy matter, it cost blood; and not any blood, such as He could well spare, but it cost Him His life-blood. It could not be the blood of the Testament, but there must be a Testament; and a Testament there cannot be, but the Testator must die. So He died, He was brought to the dead for it. This blood brought Him to His testament, which is further than blood.

We said there were two acts; 1. One expressed ‘brought Him thence,’ αναγαγων. The other implied, ‘brought Him thither,’ αγαγων. But first, brought thither,’ before ‘brought thence.’ We will touch them both. 1. Why brought thither, and how? 2. and why brought thence, and how?

If when He was ‘brought thence’ it was peace, when He was ‘brought thither,’ it was none. How came it there was none? What made this separation? That did sin, sin break the peace.

Why, sin touched not Him, ‘He knew no sin.’ True; it was not for Himself or any sin of His. Whose then? Here are but two, 1. Pastor, and 2. ovium; Pastor He, ovium, we. If not the Shepherd’s then the sheep’s sin; if not His, ours. And so it was; peccata vestra, saith God in Esay, and speaks it to us. No quarrel He had to the Shepherd; nothing to say to Christ, as Christ. But He would needs be dealing with sheep, and His sheep fell to straying, and light into the wolves’ den; and thither He must go to fetch them, if He will have them.

For ovium then is all this ado, and that is, for us. For all we, ‘as sheep, had gone astray.’ I may say further; all we, as sheep, were appointed to the slaughter. So it was we should have been carried thither, and the Lord laid upon Him the transgressions of us all, and so He was carried for us. This Pastor became tanquam ovis, ‘as a sheep,’ for His sheep, and was brought thither, and the wolves did to Him whatsoever they would.

As if God had said: Away with these sheep, incidant in lupos, quia nolunt regi a pastore, ‘to the wolves with them, seeing they will be kept in no fold.’ But that the Shepherd endured not; but rather than they should, He would. When it came to this, who shall go thither, Pastor or ovium, the sheep or the Shepherd? Sinite hos abire, they be His own words, ‘Let them go their way,’ let the sheep go, and ‘smite the Shepherd,’ sentence Him to be carried thither. The sheep were to be, they should have been; but the Shepherd was. In sanguine nostro it should have been; in sanguine suo, ‘His blood,’ it was. So to spare ours, He spilt His own.

Thither now He is brought, brought thither by His own blood-shedding. We can understand that well, but not how He should be brought thence by His blood. Yet the text is plain, how He was brought again, in sanguine, by His blood.

First then, let us make God, ‘the God of peace,’ and when He is so, you soon see Him ‘bring Him back again.’ That which broke the peace as we said, the very thing that carried Him to the cross, took Him down thence dead, carried Him to His grave, and there lodged Him among the dead, was sin. Away with sin then, that so there may be peace. But there is no taking away sin but by `shedding of blood’ -the blood either of Pastor or of ovium, one of them.

Why then here is blood, even the Shepherd’s blood; and shed it is, and by the shedding of it sin is taken away, and with sin God’s displeasure. It is the Apostle’s own word. ‘Hatred was slain,’ and so hatred being slain, peace followed of her own accord. ‘He was our peace,’ saith the Apostle, in one place; ‘He made our peace,’ or pacified all ‘by His blood,’ in another.

Now then, upon this peace, He that was before carried away was brought back again, and so well might be. For all being discharged, He was then to be inter mortuos liber, no longer bound, but ‘free from the dead;’not to be kept in prison any longer, but to come forth again. And by His very blood to come forth again. For it was the nature of a ransom which being laid down, the Prisoner that was brought thither is to go thence, whither He will. For a ransom hath potestatem eductivam or reductivam, ‘a power to bring forth, or bring back again’ from any captivity.

In both these bringings, God had His hand; God bringeth to death, and bringeth back again. True, if ever, in this Shepherd. Brought Him to the dead, as’the Lord of Hosts;’ brought Him from the dead, as being now pacified, and ‘the God of peace.’ Out of His justice, God smote the Shepherd; out of His love to His sheep, the Shepherd was smitten. But Quem deduxit iratus, reduxit placatus; ‘Whom of His just wrath against sin He brought thither, now having fulfilled all righteousness He was to bring thence again.’ And so brought back He was, and the same way that He was carried thither. Carried the way of justice, to satisfy for them He had undertaken for. And having fully satisfied for them, was in very justice to be brought back again. And so He was; God accepted His passion in full satisfaction, gave present order for His raising again.

And let not this phrase of God’s bringing back, or of Christ’s coming back, of God’s raising Him, or of Christ’s rising, any-thing trouble you. The resurrection is one entire act of two joint Agents, that both had their hands in it. Ascribed one while to Christ Himself, that He rose, that He came back; to shew that He had ‘power to lay down His life, and power to raise it again.’ Another while to God, that He raised Him, that He brought Him back; to shew that God was fully satisfied and well-pleased with it, reach him His hand, as it were, to bring Him thence again.

To shew you the benefit that riseth to us by this His rising. Brought thither He was to the dead: so, it lay upon us; if He had not, we should. We were ever carrying thither; and that we might not, He was. Brought thence He was, from the dead: so it stood us in hand; if He had not been brought thence, we should never have come thence, but been left to have lain there world without end.

Brought thither He would be–He and not we; He without us. So careful He was not to spare Himself that we might be spared. Brought thence He would not be, not without His sheep we may be sure. He would bring us thence too, or He would not be brought thence without us. You may see Him in the parable, coming with His lost sheep on His shoulders. That one sheep is the image of us all. So careful He was, as He laid him on His own neck, to be sure; which is the true portraiture or representation of His άνάγωγή. That if ‘the God of peace’ bring Him back, He must bring them also, for He will not come back without them. Upon His bringing back from death, is ours founded; in Him all His were brought back. In His person our nature, in our nature we all.

Think you after the payment of such a price He will come back Himself alone? He will let the sheep be carried thither, and not see them brought back again? He did not suffer all this we may be sure, to come away thence, and leave them behind Him. It was never seen that any that paid after so high a rate for any, be it what it will, that when He had done would not see it brought away, but lose all His labour and cost. No; as sure Himself was brought, so sure He will bring them whom He would not part from, He will die first. Nothing shall part them now. Pastor and ovium,”sheep” and “Shepherd” now, or no bargain. He with His flock, and His flock with Him; it with Him and He with it; He and they, or not He Himself; both together, or not at all.

Will you hear Himself say as much? “Father, My will is, that whither I go,” whence I come, where I am, thither, thence, and there, “these be also.”

But when He had brought us thence, what shall become of us trow? Will He leave us at random to wander in the mountains? No; but ubi desinit pastor, ibi incipit testator; ‘where the Shepherd goes out, the testator comes in.’ Which we find plainly in the word testament. For though peace be a fair blessing in itself, if no more but it; and bringing back be worth the while, yet here is now a greater matter than so. There is more in the blood than we are aware of. This is also meant; that there is the blood of a testament, which bodeth some further matter. There should need no testament, if it were for nothing but to make peace. A covenant would serve for that; ‘My covenant of peace would I make with thee,’ saith God. Sanguis foederis would have done that, if there had been no more but so. But here it is the blood of a testament.

It is sanguis cum testamento annexo, ‘blood with a testament annexed.’ Beside the pacification and back-bringing, this Scripture ‘offereth more grace;’ even a testamentary matter to be administered for our further behoof.

For I ask. Every drop of this blood is more worth than many worlds: Shall this blood then so precious, of so great a Person as the Son of God, be spent to bring forth nothing but pardon and peace? Being of so great a value, shall it produce but so poor an effect? Pity it should be shed, to bring forth nothing but a few sheep from death. There is enough in it to serve further to make a purchase, which He may dispose of to them He will vouchsafe to bring again from the dead. For when He hath brought them thence, how He will dispose them, that would be thought on too.

I find then ascribed to His blood, a price; not only of άπολυtρωσις, that is a ‘redemption or ransom,’ but also, περιοησις, that is, of ‘perquisition or purchase.’ And I find them both in one verse. So that this blood availed, as to pay our debt, so over and above to make a purchase; served not only to procure our peace, but to state us in a condition better than ever we were before. Not only brought us, but bought us; nay not only bought us and brought us back, but bought for us further an everlasting inheritance and brought us to it.

Two powers were in it; 1. as sanguis foederis, ‘the blood of the covenant,’ the covenant of peace, for in blood were the covenants made; that with Abraham in Genesis fifteen, that with Moses in Exodus twenty-four, in blood both; and among the heathen men, never any covenant of peace but in blood. 2. Now for peace this were enough; but it is sanguis testamenti too, “the blood of a testament,” which is founded upon better promises, bequeaths legacies, disposeth estates–matter far of a higher nature than bare peace. As the blood of the covenant, so it pacifieth and appeaseth; as the blood of the testament, so it passeth over and conveyeth besides.

But say it did not, it were for nothing else but our peace, yet it is much better for us, that our peace go by testament rather than by a covenant. Leagues, covenants, edicts of pacification, have often been, and are we see daily broken. Small hold of them; a stronger hold than so behoved us. A stronger hold there is not than that of a testament. That is holden inviolable, never to be reversed. Nothing in rebus humanis is held more sacred; so as peace by a testament is far the surer of the twain.

Of which testament, and the greatness of it, there is much to be said, for it is not as other testaments, to be fully ‘administered;’ this shall never be so, it is ‘everlasting.’ ‘Everlasting,’ for so is He That made it;’His goings out are from everlasting.’ ‘Everlasting,’ for so is the testament itself; though it be executed in time, it was made ab æterno, and lay by Him all the while. ‘Everlasting,’ for so is the blood wherewith it is sealed, the virtue and vigour thereof doth continue as a fountain in-exhaust, never dry, but flowing still as fresh as the very first day His side was first opened. We that now live, come to it of even hand with the Apostles themselves, that were then at the opening. And they that come after us, shall not come too late, but to full as good a match as either they or we. ‘Everlasting,’ for the legacies of it are so. Not as with us, of things temporal; nor as of the former testament of the land of Canaan, now grown a barren wilderness; but of eternal life and joy and bliss, of eternity itself. And lastly, ‘everlasting,’ that we may look for no more; our Gospel is Evangelium æternum, none to come after it. This is the last, and so to last for ever.

Now lay these together, and tell me, Was He not ‘the great Shepherd’ indeed That endured this carrying thither, whence this day He came? That paid this great ransom, purchased this great estate, made this great will, disposed these great legacies, even His heavenly kingdom to His little flock? Was He not every way as good as great?–which is the true greatness, εν τω εν τό μέγα. Here with us, men be good because they be great; with God they be great because they be good; for this His great love, His great price, His great testament, was He not worthy to wear His title of Pastor magnus, of ‘Pastor’ and of ‘Testator’ both? For so both He was, and we not only His sheep but His legataries, both in His Pastorship, and in His testatorship; in His bringing forward and in His bringing backward, no ways to be severed from us. He procured no peace, shed no blood, made no testament; was neither brought to the dead nor from the dead for Himself, but for His flock, for us still. All He did, all He suffered, all He bequeathed, all He was, He was for us.

And now when all is done, then now, lo, He is the ‘Lord Jesus Christ.’ Till then a Shepherd, wholly and solely; the more are we beholden to Him. Then lo, He tells us His name, that He is’the great Shepherd,’ He that was brought back; the blood His, His the Testament. Truly called ‘the Testament;’ there can no inventory be made of this. It hath not entered in the heart of man to conceive what things God hath prepared for those that have their part in this Testament, above all that we can desire or imagine. Upon earth there is no greater thing than a kingdom; and no less than a ‘kingdom it is His Father’s will to dispose unto us.’ But a kingdom eternal, all glorious and blessed, far above these here.

All this is a good hearing; hitherto we have heard nothing but pleaseth us well. God at peace; the Shepherd brought to death, that we might not; and brought from death, that we also might be brought from thence; and not brought and left to the wide world, but farther to receive those good things which are comprised in his Testament. This is done, done by him for us. Now to that which is to be done, to be done by us. Not for Him–I should not do well to say so- but indeed for ourselves. For so, for us in the end it will prove; both what He did, and what we do ourselves.

That which on our part the Apostle wisheth us is, that we may be so happy as that God would in effect do the same for us He did for Him, that is, bring us back; back from our sinful course of life to a new, given to do good works.

The Resurrection is here termed άναγωγή, ‘a bringing back.’ So that any bringing back from the worse to the better carrieth the type, is a kind of resurrection, refers to that of Christ Who died and rose that sin might die, and that good works might rise in us. Both the time and the text lay upon us this duty, to see if good works that seem to be dead and gone, we can bring life to them and make them to rise again.

The rule of reason is, Unumquodque propter operationem suam, ‘everything is, and hath his being for the work is to do.’ And these are the works which we were born, and came into the world to do. The Apostle speaks it plainly; we were created for good works, to walk in them.” And again, ‘That we were redeemed to be a people zealously given to good works.’ So they come doubly commended to us, as the end of our creation and redemption both.

In this text we see, it is God’s will, it is His good pleasure we do them, if we any thing regard either His will or pleasure.

In this text, the Apostle prays that we may ‘be made perfect in them.’ So, imperfect we are without them; imperfect we, and our faith both. ‘For by works is our faith made perfect,’ even as Abraham’s faith was. And the faith that is without them, is not only imperfect, but stark dead; so as that faith needs a resurrection, to be brought from the dead again.

And whatsoever become of the rest, in this text it is that He hath not left them out, nor unremembered in his testament. They are in it, and divers good legacies to us for them. Which, if we mean to be legataries, we must have a care of. For as His blood serveth for the taking away of evil works, so doth His testament for the bringing again of good. And as it is good philosophy, unumquodque propter operationem suam, so this is sure, it is sound divinity, unusquisque recipiet secundum operationem suam. At our coming back from the dead whence we all shall come, we shall be disposed of according to them; receive we shall, every man, ‘according to his works.’ And when it comes to going, they that have done good works shall go into everlasting life; and they, not that have done evil, but they that have not done good, shall go–you know whither. Let no man deceive you; the root of immortality, the same is the root of virtue–but one and the same root both. When all is said that can be, naturally and by very course of kind, good works, you see, do rise out of Christ’s resurrection.

‘Make you perfect’–so we read it; which shews we are, as indeed we are, in state of imperfection till we do them. Nay, if that be all, we will never stick for that; cognoscimus imperfectum nostrum, we yield ourselves for such, for imperfection; and that is well. But we must so find and feel our imperfection, that as the Apostle tells us in the sixth chapter before, “`we strive to be carried forward to perfection’ all we may. Else, all our cognoscimus imperfectum, will stand us in small stead.

Why, is there any imperfection in this life? There is: else, how should the Apostle’s exhortation there, or his blessing here take place. I wot well, absolute, complete, consummate perfection, in this life there is none. Non puto me comprehendisse, saith St. Paul, ‘I count not myself to have attained?’ No more must we, not ‘attained.’ What then?’But this I do,’ saith he, and so must we; ‘I forget that which is behind, and endeavour myself, and make forward still, to that which is before.’ Which is the perfection of travellers, of wayfaring men; the further onward on their journey, the nearer their journey’s end, the more perfect; which is the perfection of this life, for this life is a journey.

Now good works are as so many steps onward. The Apostle calls them so, ‘the steps of the faith of our father Abraham,’ who went that way, and we to follow him in it. And the more of them we do, the more steps do we make; the further still shall we find ourselves to depart from iniquity, the nearer still to approach unto God in the land of the living; whither to attain, is the total or consummatum est of our perfection.

But not to keep from you the truth, as it is, the nature of the Apostle’s word καταρτίσαι is rather to “make fit’ than ‘to make perfect.’ Wherein this he seems to say; That to the doing of good works, there is first requisite a fitness to do them, before we can do them; καταρτίσαι and ποιήσαι are both in the text. Fit to do them, ere we can do them. We may not think to do them hand over head, at the first dash. In an unfit and indisposed subject, no agent can work; not God Himself, but by miracle. Fit then we must be.

Now of ourselves, as of ourselves, we are not fit so much as ‘to think’ a good thought; it is the second of Corinthians, the third chapter, verse five. Not so much as to will, “for it is God That worketh in us to will.’ If not these two, 1. neither ‘think,’ 2. nor ‘will,’ then not to work. No more we are; neither to begin, nor having begun to go forward, and bring it to an end. Fit to none of these. Then made fit we must be, and who to reduce us to fitness but this ‘God of peace here That brought again Christ from the dead.’

Now if I shall tell you, what manner of fitness it is the Apostle’s word καταρτίσαι here doth impart, it is properly the fitness which is in setting that in, which was out of joint, in doing the part of a good bone-setter. This is the very true and native sense of the word: ‘set you in joint’ to do good works. For the Apostle tells us that the Church and things spiritual go by joints and sinews whereof they are compact, and by which they have their action and motion. And where there are joints, there may be, and otherwhiles there is a disjointing or dislocation, no less in things spiritual than in the natural body. And that is when things are miss-sorted, or put out of their right places.

Now that our nature is not right in joint is so evident, that the very heathen men have seen and confessed it.

And by a fall things come out of joint, and indeed so they did; Adam’s fall we call it, and we call it right. Sin which before broke the peace, which made the going from or departure which needed the bringing back; the same sin, here now again, put all out of joint. And things out of joint are never quiet, never at peace and rest, till they be set right again. But when all is in frame, all is in peace; and so it refers well to ‘the God of peace’ Who is to do it.

And mark again. The putting in joint is nothing but a bringing back again to the right place whence it slipped, that still there is a good coherence with that which went before; the peace-maker, the bringer-back, the bone-setter, are all one.

The force or fulness of the Apostle’s simile,’out of joint,’ you shall never fully conceive till you take in hand some good work of some moment, and then you shall for certain. For do but mark me then, how many rubs, lets, impediments, there will be, as it were so many puttings out of joint, ere it can be brought to pass. This wants, or that wants; one thing or other frames not. A sinew shrinks, a bone is out, somewhat is awry; and what ado there is ere we can get it right! Either the will is averse, and we have no mind to it; or the power is shrunk, and the means fail us; or the time serves not; or the place is not meet; or the parties to be dealt with, we find them indisposed. And the misery is, when one is got in, the other is out again. That the wit of man could not have devised a fitter term to have expressed it in. This for the disease.

What way doth God take to set us right? First, by our ministry and means. For it is a part of our profession under God, this name καταρτίσμός, to set the Church in, and every member that is out of joint. You may read it in this very term προς καταρτίσμόν. And that we do, by applying outwardly this Testament and the blood of it, two special splints as it were, to keep all straight. Out of the Testament, by ‘the word of exhortation,’ as in the next verse he calls it, praying us to suffer the splinting. For it may sometimes pinch them, and put them to some pain that are not well in joint, by pressing it and putting it home. But both by denouncing, one while the threats of the Old Testament, another while by laying forth the promises of the New, if by any means we may get them right again. This by the Testament, which is one outward means. The blood is another inward means. By it we are made fit and perfect, (choose you whether,) and that so, as at no time of all our life we are so well in joint, or come so near the state of perfectness, as when we come new from the drinking of that blood. And thus are we made fit.

Provided that καταρτίσαι do end, as here it doth, in ποιήσαι and έν έργω; that all this fit-making do end in doing and in a work, that some work be done. For in doing it is to end, if it end aright; if it end as the Apostle here would have it. For this fitting is not to hear, learn, or know, but ‘to do His will.’ We have been long at “Teach me Thy will, at that lesson. There is another in Psalm one hundred and forty -three, ‘Teach me to do Thy will’ ; we must take out that also. “Teach me Thy Will” and “Teach me to do Thy Will” are two distinct lessons. We are all our life long about the first, and never come to the second, to είς τό ποιήσαι. It is required we should now come to the second. είς τό ποιήσαι We are not made fit, when we are so, to do never a whit the more; καταρτίσαι is to end in ποιήσαι, which is doing, and in έργον , that is, in a ‘work.’

In work, and ‘in every good work.’ We must not slip the collar there, neither. For if we be able to stir our hand but one way and not another, it is a sign it is not well set in. His that is well set, he can move it to and fro, up and down, forward and backward; every way, and to every work. There be that are all for some one work, that single some one piece of God’s service, wholly addicted to that, but cannot skill of the rest. That is no good sign. To be for every one, for all sorts of good works, for every part of God’s worship alike, for no one more than another, that sure is the right. So choose your religion, so practise your worship of God. It is not safe to do otherwise, nor to serve God by Synecdoche; but εν παντί, to take all before us.

But in the doing of all or any, beside our part, είς τό ποιήσαι, here is also ποιων έν ύμίν, a worker besides. For when God hath fitted us by the outward means, there is not all. He leaves not us to ourselves for the rest, but to that outward application of ours joins His ποιων έν ύμίν, an inward operation of His own inspiring, His grace, which is nothing but the breath of the Holy Ghost. Thereby enlightening our minds, inclining our wills, working on our affections, making us homines bonae voluntatis; that when we have done well, we may say with the Prophet, Domine universa opera nostra operatus Es in nobis, ‘Lord, all our good works Thou hast wrought in us.’ Our works they be, yet of Thy working. And with the Apostle, ‘we did them, yet not we, but the grace of God that was with us.’ Both ways, it is true: what He works by us He works in us, and what He works in us He works by us. For ένεργεί, συνεργεί, take not away one the other, but stand well together. This for the doing.

Now for the work. In every good work we do His will; yet, it seemeth, degrees there are. For here is mention of θέλήμα, ‘His will;’ and besides it, of ενάρεστον, ‘His good pleasure,’ and this latter sounds as if it did import more than a single will. One’s good pleasure is more than his bare will. So in the chapter before he wisheth, λατρένσαι εναρέστως, that is, we may serve and please; that is, may so serve as that we may please. Acceptable service then is more than any, such as it is. There is no question but that, as of evil works some displease God more than other, so of good works there are some better pleasing, and that He takes a more special delight in.

And if you would know what they be, above at the sixteenth verse it is said, that ‘to do good and to distribute,’ that is, distributive doing good, it is more than an ordinary service; it is a sacrifice, every such work. It is of the highest kind of service, and that with that kind, (εναρεστείται, our word here) ‘God is highly pleased.’ So doth St. Paul call the bounteous supplying of his wants from the Philippians, θνσίαν δεκτήν, ‘a sacrifice right acceptable and pleasing to God,’ and όσμήν ύωδίας, ‘a most delightful sweet savour.’ And that you may still see He looks to the Resurrection, He saith, the Philippians had lain dead and dry a great while, as in winter trees do use. But when that work of bounty came from them, they did άναθάλλειν, ‘that is shoot forth, wax fresh, grow green again,’ as now at this season plants do. That so the very virtue of Christ’s resurrection did shew forth itself in them; so fitting nature’s resurrection time, the time of bringing things as it were from the dead again, with this of Christ. Which time is therefore the most pleasing time, the time of the greatest pleasure of all the times of the year. So, we know, how to do that is pleasing in His sight.

Yet even this pleasing and all else is to conclude, as here it doth, with ‘through Jesus Christ our Lord:’ He is in here too. In, at the doing; in, at the making them to please God, ut faciat quisque per Christum, quod placeat per Christum, ‘that what by Christ is done, by Christ may please when it is done.’ In at the doing, infundendo gratiam, gratiam activam, ‘by infusing, or dropping in His grace active;’ making us able and fit to do, and so to do them. In at the pleasing, affundendo graqtiam, gratiam passivam, ‘bypouring on His good grace and favour passive,’ as it might be some drops of His blood, whereby it pleaseth being done. Gracing His work, as we use to say, in God’s sight, that so He of His grace may crown it

We have gone through with both points. Now comes the hardest point of all, the sequel, to couple them and make them hang well together.

First then, they be ascribed to ‘the God of peace.’ There are but three things to be done in the text, and peace doth them all. And if peace, then God by no other title than ‘the God of peace.’ 1. Peace bringeth from death; for war, I am sure, brings to death many a worthy man. There is little question to be made of this; that ‘the God of peace’ doth the one, but the devil of discord doth the other.

Secondly, peace sets in joint, war brings all out of joint; war is not good for the joints as we see daily, peace doth them no hurt.

Thirdly, peace makes us fit for good; war for all manner of evil works, saith St. James in the third chapter, verse sixteen. Therefore ‘the God of peace,’ say we. And if it He take it from us for a time, that He bring it quickly back to us again. For when He was first brought into the world, among the living, at His birth, Janus was shut; the Angels, they sung ‘peace upon earth.’ And when He was ‘brought again from the dead’ this day, He was no sooner risen but the first news was, the soldiers ran all away–a sign of peace. And indeed, when He had slain hatred, it was most kindly then, to bring peace. At this evening with His own mouth He spoke it once and twice, pax vobis, over and over again, which is the Apostle’s benediction here. So resurrection and peace, they accord well.

Now for the sequel of good works, upon Christ’s bringing from the dead. Being to infer good works, He would never put in all this, of Christ’s bringing back again from the dead, if there had not been some special operative force to, or towards them, in Christ’s resurrection. If Christ’s rising made not for them, had not some special reference to them, some peculiar interest in them, all this had not been ad idem, but idle, and beside the point quite. We must take heed of this error, to think the passion or resurrection of Christ, though it be actus transiens that with the doing passeth away, that it hath not a virtue and force permanent; that it left not behind it a virtue and force permanent to work continually some grace in us; as to think His resurrection to be actus suspensus, an act to have his effect at the latter day, and in the mean time to serve for nothing but to hang in nubibis, as they say. But that this day it hath an efficacy continuing, that sheweth forth itself; and, as the rule is, in the soul, before it doth on the body. We shall leave the heathen to their habits and habitualities, but with us Christians this is sure: whatsoever in us, or by us is wrought, that is pleasing to God, it is so wrought by the virtue of Christ’s resurrection. We have not thought of it perhaps, but most certain it is so. So God hath ordained it. Whatsoever evil is truly mortified in us, it is so by the power of Christ’s death, and thither to be referred properly. And whatsoever good is revived or brought again anew from us, it is all from the virtue of Christ’s rising again. All do rise, all are raised, thence. The same power that did create at first, the same it is that makes a new creature. The same power that raised Lazarus the brother from his grave of stone, the same raised Mary Magdalene the sister from her grave of sin. From one and the same power both. Which keepeth this method; worketh first to the raising of the soul from the death of sin; and after, in the due time, to the raising of the body from the dust of death. Else, what hath the Apostle said all this while?

Now this power is inherent in the Spirit as the proper subject of it, even the eternal Spirit, whereby Christ offered Himself first unto God, and after raised Himself from the dead. Now as in the texture of the natural body ever there goes the spirit with the blood; ever with a vein, the vessel of the one, there runs along an artery, the vessel of the other, so is it in Christ; His blood and His Spirit always go together. In the Spirit is the power; in the power virtually every good work it produceth, which it was ordained for. If we get the Spirit, we cannot fail of the power. And the Spirit that ever goes with the blood, which never is without it.

This carries us now to the blood. The very shedding whereof upon the cross, primum et ante omnia was the nature of a price. A price, first, of our ransom from death due to our sin, through that His satisfaction. A price again of the purchase He made for us, through the [a]vail of His merit, which by His testament is by Him passed over to us.

Now then, His Blood, after it had by the very pouring it out wrought these two effects, it ran not waste, but divided into two streams. 1. One into ‘the laver of the new birth’–our baptism, applied to us outwardly to take away the spots of our sin. 2. The other,’into the Cup of the New Testament in His Blood,’ which inwardly administered serveth, as to purge and ‘cleanse the conscience from dead works’ that so live works may grow up in the place, so to endue us with the Spirit that shall enable us with the power to bring them forth. Hæc sunt Ecclesiae gemina Sacramenta, ‘these are,’ not two of the Sacraments, but ‘the two twin Sacraments’ of the Church, saith St. Augustine. And with us there are two rules. 1.One, Quicquid Sacrificio offertur, Sacramento confertur; ‘what the Sacrifice offereth, that the Sacrament obtaineth.’ 2. The other, Quicquid Testamento legatur, Sacramento dispensatur;’what the Testament bequeatheth, that is dispensed in the holy mysteries.’

To draw to an end. If this power be in the Spirit, and the blood be the vehiculum of the Spirit, how may we partake this blood? It shall be offered you straight ‘inthe Cup of blessing, which we bless in His name.’ For ‘is not the Cup of blessing which we bless, the communion of the Blood of Christ,’ saith St. Paul? Is there any doubt of that? In which Blood of Christ is the Spirit of Christ. In which Spirit is all spiritual power; and namely, this power that frameth us fit to the works of the Spirit, which Spirit we are all made there to drink of.

And what time shall we do this? What time is best? What time better than that day in which He first shewed forth the force and power He had in making peace, in bringing back Christ That brought peace back with Him, That made the Testament, That sealed it with His Blood, That died upon it, that it might stand firm for ever? All which were done upon this day. This day then somewhat would be done, somewhat more than ordinary, more than every day. Let every day be for every good work, to do His will; but this day to do something more than so, something that may be well-pleasing in His sight. So it will be kindly, so we shall keep the degrees in the text, so we shall give proof that we have our part and fellowship in Christ, in Christ’s resurrection;–grace rising in us, works of grace rising from it. That so, there may be a resurrection of virtue, and good works at Christ’s resurrection. That as there is a reviving άναθαλία in the earth, when all and every herbs and flowers are ‘brought again from the dead,’ so among men good works may come up too, that we be not found fruitless at our bringing back from the dead, in the great Resurrection, but have our parts as here now in the Blood, so there then in the Testament, and the legacies thereof, which are glory, joy and bliss, for ever and ever.

AMEN.

An organ voluntary is inserted here, following the pattern described by James Clifford in his The divine services and anthems usually sung in His Majesties chappell and in all cathedrals and collegiate choires in England and Ireland (London, 1664).

THE CHOIR SINGS AN ANTHEM: Christ our Paschal Lamb by Adrian Batten

Priest

After suche Sermon, homely, or exhortacion, the Curate shall declare unto the people, whether there be anye holy dayes or fastynge dayes the weke folowyng, and earnestly exhorte theim to remembre the poore, saying one, or moe of these sentences following, as he thinketh most convenient by his discretion.

Holy Communion continues with the Officiant’s informing the congregation of Holy Days or days of Fasting. We probably should have had the priest announce services planned at the Cathedral for the Holy Days of Easter Monday and Easter Tuesday, occasions for which Propers are provided in the Prayer Book. But we didn’t. Instead, we do have the Officiant fulfill the second specified task in this rubric, the task of inviting the congregation to contribute money to the support of the poor. He does this by proclaming a verse or verses chosen from a collection of biblical verses found at this point in the Prayer Book. For the complete list of 20 verses, consult a copy of the 1559 or1604 Prayer Books.

LET your light so shyne before men, that they maye see your good workes, and glorifye youre father whyche is in heaven.

Laye not up youreselves treasure upon the earthe, where the ruste and mothe doeth corrupte, and where theeves breake through and steale: But lay up for youreselves treasures in heaven, where neyther rust, nor motthe doeth corrupt, and where theeves do not breake thorowe and steale.

Blessed be the man that provydeth for the sycke, and nedy, the Lorde shall deliver him, in the time of trouble.

Then shal the Churchewardens, or some other by them appoyncted, gather the devocion of the people, and put the same into the poore mens boxe, and upon the offeryng daies appoincted, every man and woman shal pay to the Curate the due and accustomed offerings, after whiche done, the Priest shal saie.

Let us pray for the whole estate of Christes Churche militant here in earth.

ALMIGHTYE and everliving God, whych by thy holye Apostle hast taughte us to make prayers and supplicacyons, and to geve thanckes for all men: We humbly beseche thee moste mercifully (to accepte our almose) and to receyve these our prayers whyche of we offer unto thy divine majestie, beseechyng the to inspire continually, the universal Churche wyth the spiryte of truthe, unitye, and concorde: And graunt that all they that do confesse thy holy name, may agree in the truthe of thy holy woorde, and lyve in unytye and godlye love. We beseche thee also to save and defend alle Christyane Kynges, Prynces, and Governours, and specially thy servaunt, Elyzabeth our Quene that under her we may be godly and quietly governed: and graunt unto her whole Counsaill, and to all that be put in aucthoritye under her, that they may truely and indifferently minister justice, to the punishement of wyckednes and vice, and to the maintenaunce of goddes true religion and vertue. Give grace (O heavenly Father) to al Bishopes, Pastours and Curates, that they may bothe by theyr life and doctrine set furth thy true and lively worde and rightely and duely administer thy holy Sacramentes: and to all thy people gyve thy heavenlye grace, and especially to thys congregacion heare present, that with meke harte and due reverence, they may heare and receive thy holy worde, truely servyng the in holines and ryghtuousnes all the dayes of theyr lyfe. And we moost humbly beseche the of thy goodnes (O Lord) to comfort and succoure all theym whyche in thys transitory lyfe bee in trouble, Sorowe, nede, sicknes, or any other adversity. Graunt this, O father, for Jesus Christes sake our onely Mediatour and advocate. Amen

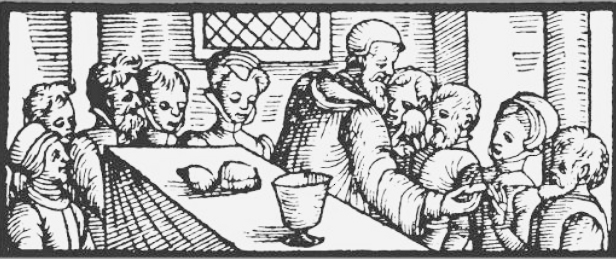

William Harrison, in his Description of England, notes that this moment in the Communion service is at a potential break point. Clergy were to celebrate Holy Communion only when several members of the congregation had indicated their interest in doing so. Given that Easter Sunday was one of the days in which reception of Holy Communion was required by law, one must presume that priests in parish churches across England on Easter Sunday 1624 would have made this possible by completing the entire service. But that was not always the case. Harrison describes what happened when the priest did not have enough participants to enable him to continue, private celebrations having been abolished at the Reformation. Harrison describes the process thusly: “This being done, we proceed unto the communion, if any communicants be to receive the Eucharist; if not, we read the Decalogue, Epistle, and Gospel, with the Nicene Creed (of some in derision called the “dry communion”), and then proceed unto an homily or sermon, which hath a psalm before and after it, and finally unto the baptism of such infants as on every Sabbath day (if occasion so require) are brought unto the churches; and thus is the forenoon bestowed.”

Since the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer require all clergy on the staffs of cathedrals or collegiate churches to receive Communion every Sunday, we presume that at St Paul’s the full rite of Holy Communion would have been so observed. So the full service continues in our reconstruction. It does so with the reading of an exhortation. The Book of Common Prayer contains three of these; consult a copy of the Prayer Book for 1559 or 1604 to read them all. The first is to be used when “the curate shall see the people negligent to come to the Holy Communion.” It admonishes people who do not receive Communion for their negligence, for they are rejecting God’s gracious invitation. The second of the three is to be used “at the discretion of the curate,” and consists of a warning against receiving Communion unworthily, for doing so will “increase your damnation.” Then the Prayer Book rubric says, of the third exhortation, “Then shall the priest say this exhortation.” This required exhortation mixes the subjects of the first two. Those who come to receive the bread and wine are promised that if they come “with a truly penitent heart and lively faith,” they will “spiritually eat the flesh of Christ, and drink his blood, then we dwell in Christ, and Christ in us, we be one with Christ, and Christ with us.” But if they receive unworthily, they will “eat and drink our own damnation.”

We have recorded the Cathedral’s use of this third, required exhortation, but not the other two. Cathedral clergy were, after all, directed by the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer to “receive the communion . . . every Sunday at the least,” unless, of course, “they have a reasonable cause to the contrary.”

Priest

The Exhortation

DERELY beloved in the Lorde: Ye that mynde to come to the holye Communion of the bodye and bloude of oure savioure Christe, must consyder what saincte Paule writeth unto the Corinthiens, howe he exhorteth all persones diligentlye to trye and examyne them selves, before they presume to eate of that breade, and drincke of that cuppe. For as the benefyte is greate, yf wyth a trulye penitente herte and lyvely faith we receive that holy sacrament (for then we spiritually eate the fleshe of Christ, and drincke his blonde, then we dwell in Christe and Christe in us, we be one wyth Christ, and Christe with us) so is the daunger great, if we receyve the same unworthely. For then we be gilty of the body and bloud of Christ our saviour. We eate and drincke our owne dampnation, not considering the lordes bodye. we kindle Gods wrath against us, we provoke him to plague us with divers diseases, and sundrye kyndes of death. Therfore if any of you be a blasphemer of god, an hinderer or slaunderer of his worde, an adulterer, or be in malyce or envye, or in anye other grevous crime, bewaile your Sinnes, and come not to this holy table, lest after the taking of that holy sacrament, the devil enter into you, as he entred into Judas, and fil you full of al iniquities, and bring you to destruction both of bodye and soule. Judge therefore your selves (brethren) that ye be not judged of the Lord. Repent you truly for your sinnes past, have a lively and stedfast faithe in Christ our saviour. Amende your lives, and be in perfect charitie wyth all men, so shal ye be mete partakers of those holy misteries. And above al thinges ye must geve most humble and herty thankes to God the father, the sone, and the holye ghost, for the redemption of the world by the deathe and passion of our saviour Christ, bothe God and man, who did humble him selfe, even to the deathe, upon the crosse, for us miserable sinners which lay in darckenes, and shadowe of death, that he mighte make us the children of God, and exalte us to everlasting life. And to thende that we should alwaie remembre the exceadinge greate love of our master and onelie saviour Jesu Christ, thus diyng for us, and the innumerable benefites (which by his precious bloudsheading) he hath obteined to us, he hath instituted and ordeined holy misteries, as pledges of his love, and continuall remembraunce of his death, to our great and endles comfort. To him therfore with the father and the holye Ghost, let us geve (as we are moste bounden) continuall thankes, submitting our selves wholy to his holie will and pleasure, and studiyng to serve him in true holines and righteousnes, al the daies of our life.

Priest+ Choir Amen.

The overall argument of our reconstruction of worship at St Paul’s is, throughout, that the Church of England from its beginning was corporate, liturgical, and sacramental, that words like “faith,” “worship,” “belief,” “prayer,” and “communion” take their meaning from their use in public, corporate worship, that the Prayer Book Rites enable the English to live their lives meaningfully and hopefully through the ways in which the private and personal dimensions of their lives are supported and blessed by being brought into the public, corporate worship of the community and the nation. The invitation which the priest reads next in the Communion Service summarizes succinctly the structure, progress, and significance of that life.

Then shall the Priest saye to them that come to receyve the holy Communion.

You that do truly and ernestly repente you of youre sinnes, and be in love, and charite with your neighbors and entende to lede a newe lyfe, folowing the commaundementes of God, and walkynge from hence furthe in his holy waies: Draw nere and take this holy Sacrament to your comforte make your humble confession to almighty God, before this congregation here gathered together in his holye name, mekely knelynge upon your knees.