Early History

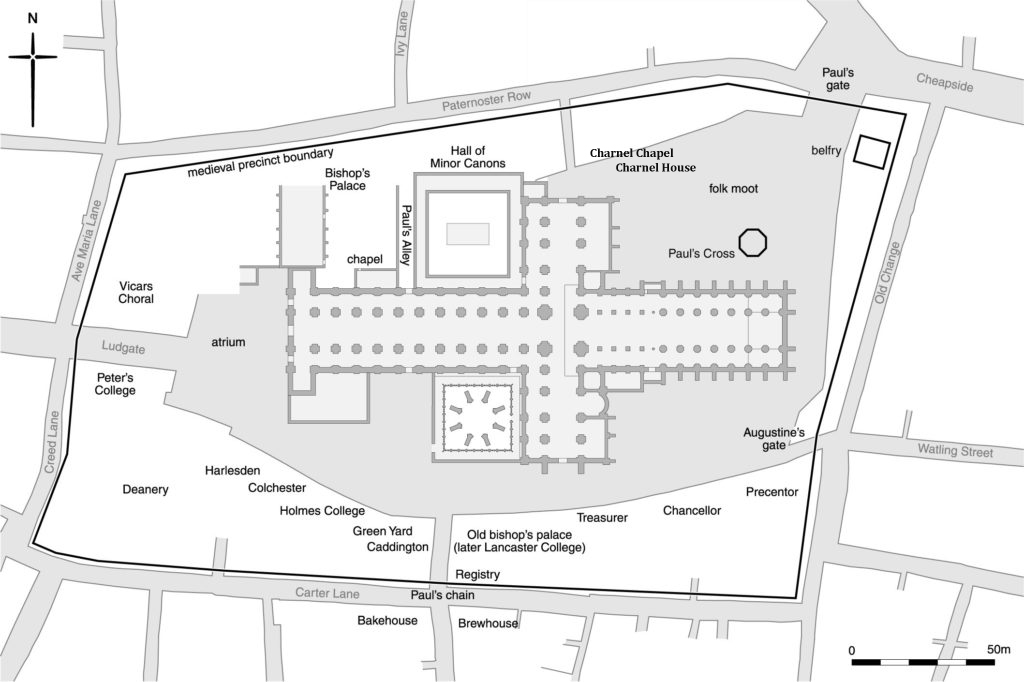

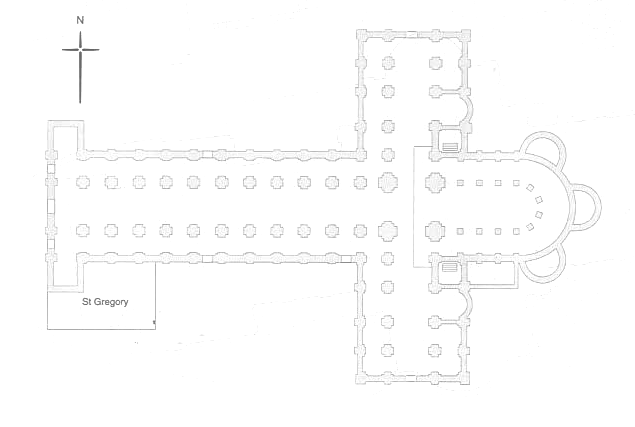

St Paul’s Cathedral in 1621, when John Donne became its Dean, was a building that had been constructed in two basic phases. The first, begun toward the end of the eleventh century, was built to replace an earlier cathedral which was destroyed by fire around 1087. The cathedral was built beginning at the east end; the Choir was completed by 1148. Construction of the Crossing and the Nave continued for nearly a hundred years, so that the resulting cathedral, completed in the Romanesque or Norman style, was not consecrated until 1240. 1

Richard Halsey has argued that the design of the interior of St Paul’s nave 2, “appears to be a design of the early 12th century that ultimately owes its three-storey elevation to Saint-Etienne, Caen.”

So, both the design for Norman St Paul’s and the stone used to construct it were imported to London from Normandy, yet another dimension of the Norman Conquest.

The second phase of construction began in 1256, in part in response to the change between Romanesque architecture, with its rounded arches and heavy walls, to Gothic style, with its pointed arches, larger windows, and thinner walls supported by flying buttresses.

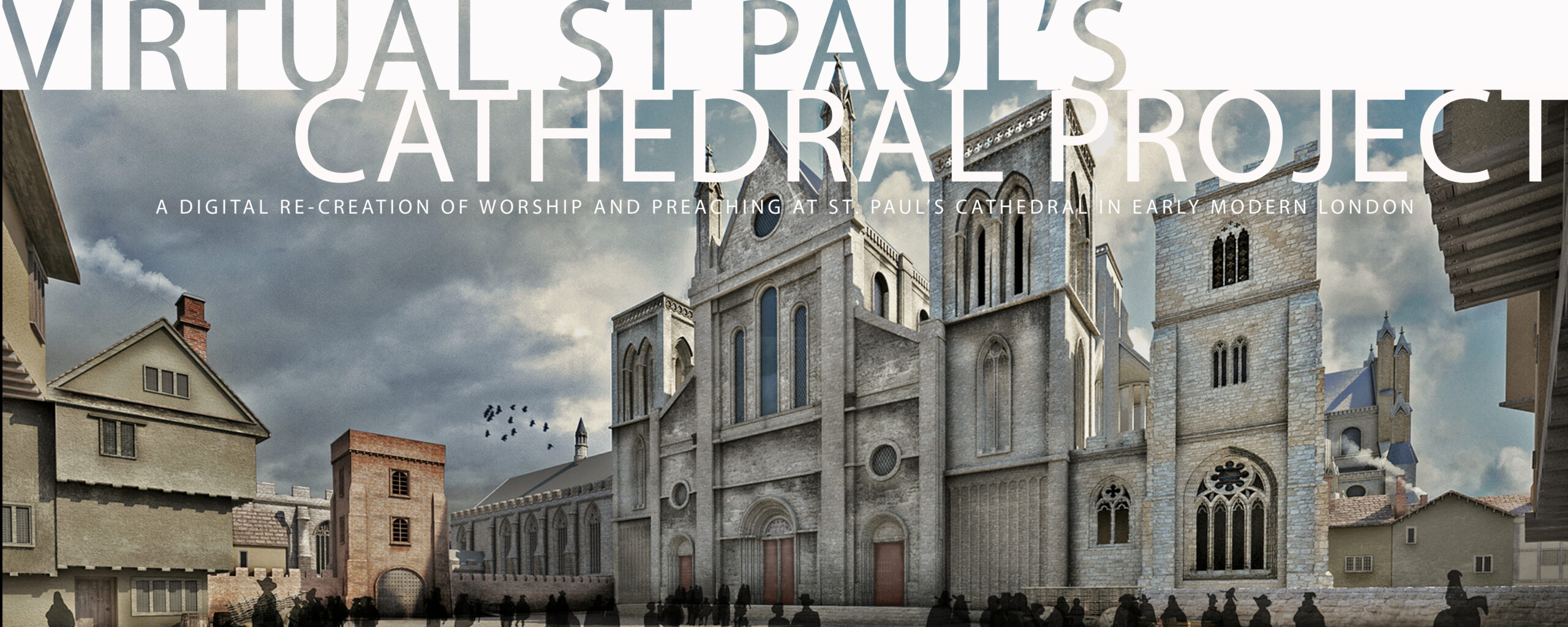

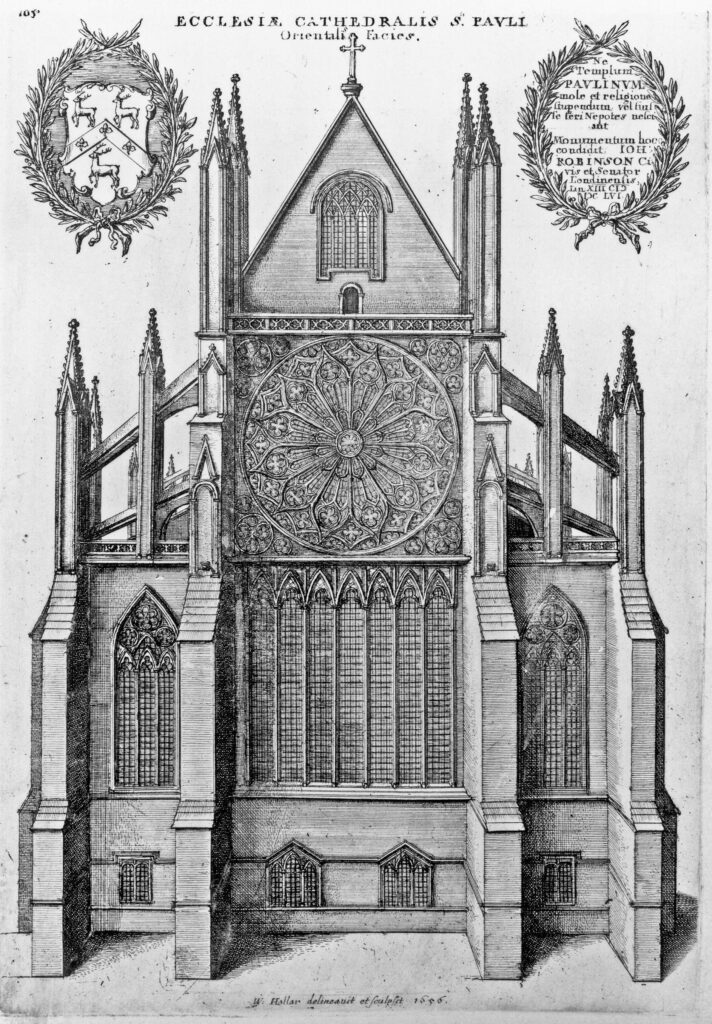

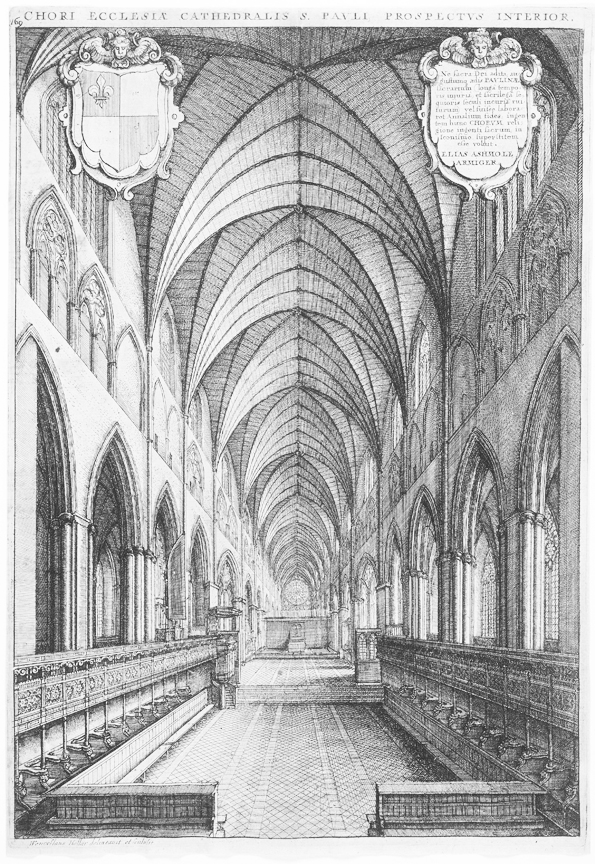

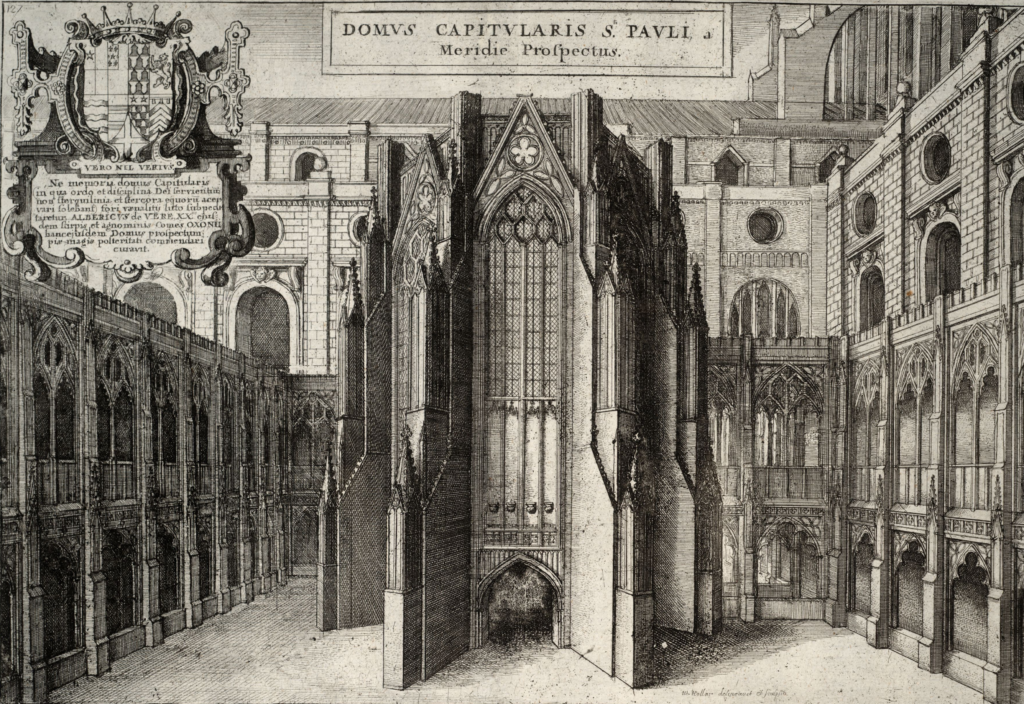

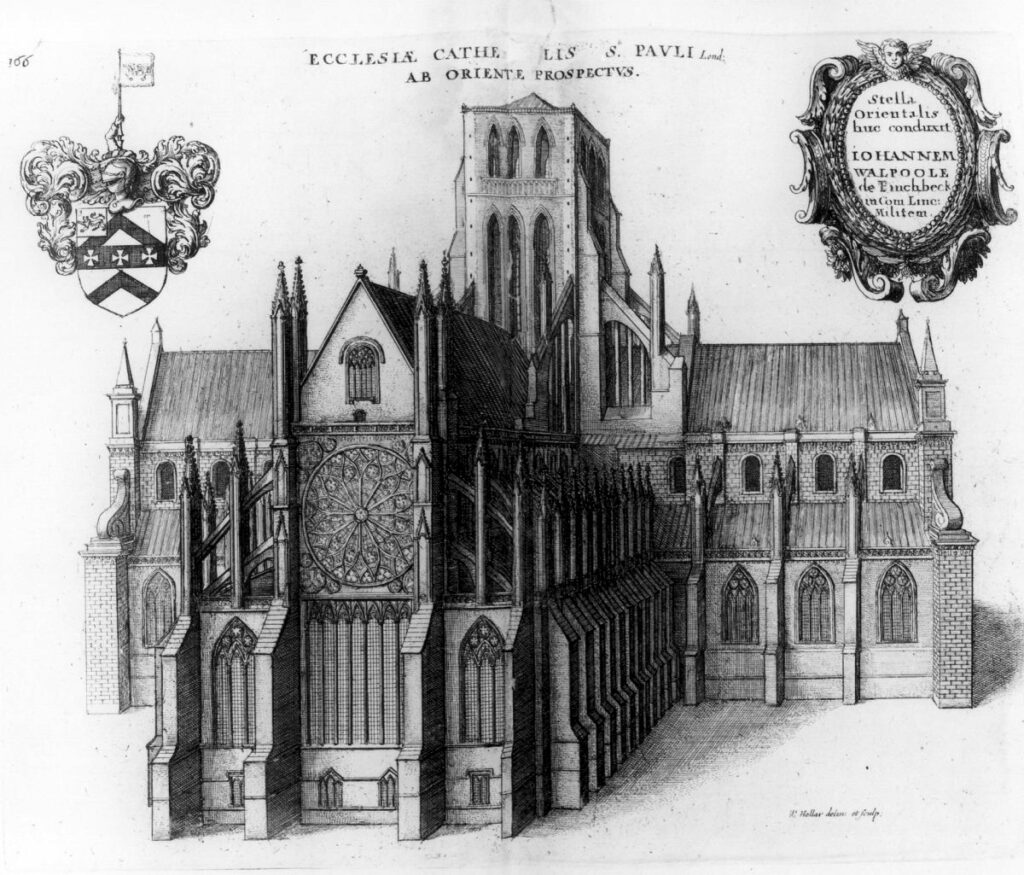

Images of St Paul’s Cathedral by Wenceslaus Hollar. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

This “New Work” included replacement of the Choir and part of the transepts. This part of St Paul’s Cathedral was consecrated in 1300 but not completed until 1314.

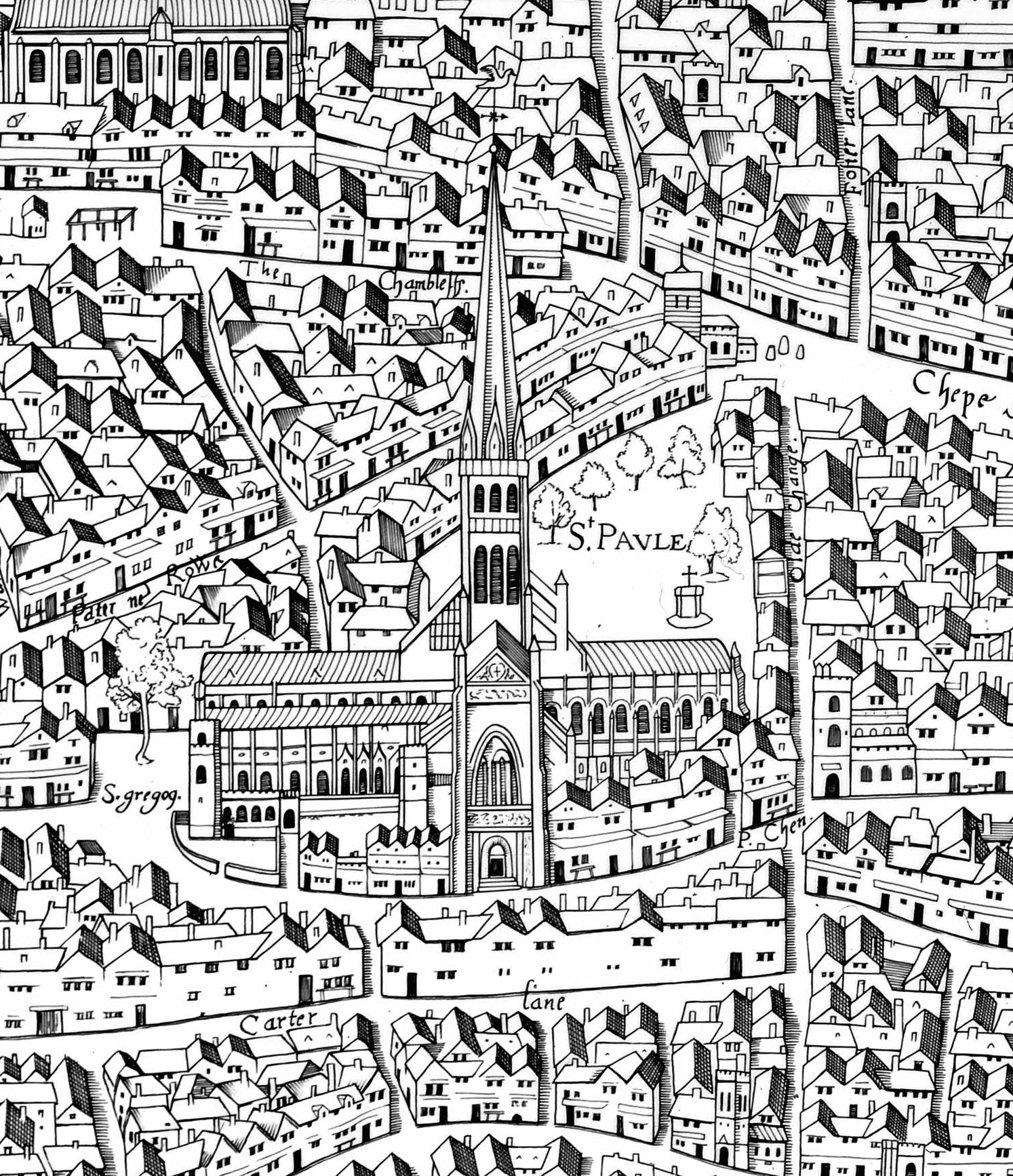

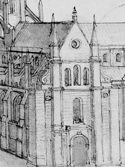

The image of St Paul’s from the Copperplate Map of the mid-1500’s shows the completed Cathedral, with its spire of some 204 feet in height. This spire was destroyed by a fire started by a lightning strike in 1561.

St Paul’s Cathedral, Detail from the

Copperplate Map (1550?). Image

courtesy the Museum of London.

In the Time of Donne

As a result, when Donne became Dean in 1621, at least parts of the building’s nave had been standing for over 400 years. The Choir had been completed for over 300 years. It was common knowledge in the early years of the 17th century that the building was in serious need of repair. As someone once reminded me, the windows had not been washed in 400 years.

Exactly how the Cathedral showed signs of its age has not been specified, but one can easily imagine leaking roofs, broken or missing windows, and the occasional stone falling from the ceiling. Several efforts were made to raise funds for renovating the building, most notably a campaign headed by John Gipkin in 1616. King James supported this effort, a considerable sum of money was raised, and building supplies were purchased and delivered to Paul’s Churchyard.

These building supplies were sitting in Paul’s Churchyard when Donne became Dean in 1621, but nothing further came of this effort. There is, in fact, a legend that the Duke of Buckingham confiscated some of these materials for repairs on his own London home. Donne’s inaction in this matter remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of his tenure as Dean.

In the Time of Inigo Jones

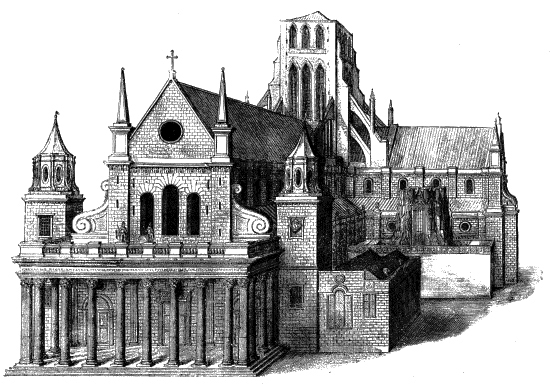

After Donne’s death, of course, efforts to refurbish the Cathedral began again, now with the support of Charles I and William Laud, by then the Archbishop of Canterbury. The architect Inigo Jones was hired, money was raised, and Jones began an ambitious program of renovation. He started with the Nave, the cathedral’s oldest section, seeking to transform it from a Norman building into a structure that drew on the classical architecture of Rome and the Italian Renaissance.

The extent of Jones’ transformation of the medieval building can be appreciated especially in his treatment of the West Front, which included, in addition to recladding the original structure, the addition of a portico with a classical colonnade and the tacking-on of various forms of neo-classical fru-fru.

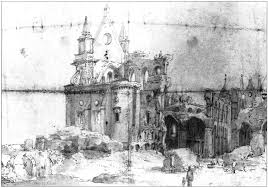

One can see quickly the difference Jones made in the look of the Nave by comparing the south side of the Nave to the left of the Chapter House and the south side to the right of the Chapter House in this image by Wenseslaus Hollar. Jones’ work apparently ran the length of the Nave and continued onto the west facade of the South Transept, but he skipped this space and left us a helpful glimpse of the original Norman architecture.

At least, he left untouched the glorious Gothic design of the Chapter House and its surrounding Cloister.

Trying to see through Jones’ remodeling work to the look of the building in Donne’s day has been one of the most challenging tasks of this Project. There is more discussion of the challenges Jones’ work posed for us in another section of this site. Let this final example suffice to communicate the feelings of this Principal Investigator.

This engraving, made after the Great Fire of 1666, shows the interior face of the South Transept, as well as details of the Crossing. If one looks at the interior of the Great Window, here, one can see the outline of that window, of a Gothic design, clearly showing that the New Work included replacing the Norman Great Window with one of Gothic design.

What Jones did was fill in the form of the Gothic window to house the frames of three tall, round-topped windows, copying his design used on the Facade of the North Transept, below.

Images of St Paul’s Cathedral: Left image by Thomas Wyck. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons; center and right images by Wenseslaus Hollar. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Jones ran out of money, or time (before the outbreak of the English Civil War), before he got any further, so the Gothic Choir in all its glory is featured in Wenseslaus Hollar’s engravings of the 1650’s, to our unending gratitude!

REFERENCES

- The most important work on the fabric of pre-Fire St Paul’s is John Schofield’s magisterial St Paul’s Cathedral before Wren (English Heritage, 2011), but see also St Paul’s: The Cathedral Church of London 604 – 2004, ed. Derek Keene, Arthur Burns, and Andrew Saint (Yale, 2004).

- In his essay in St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren on “Placing St Paul’s in the development of English greater churches” (pp. 233 – 236)