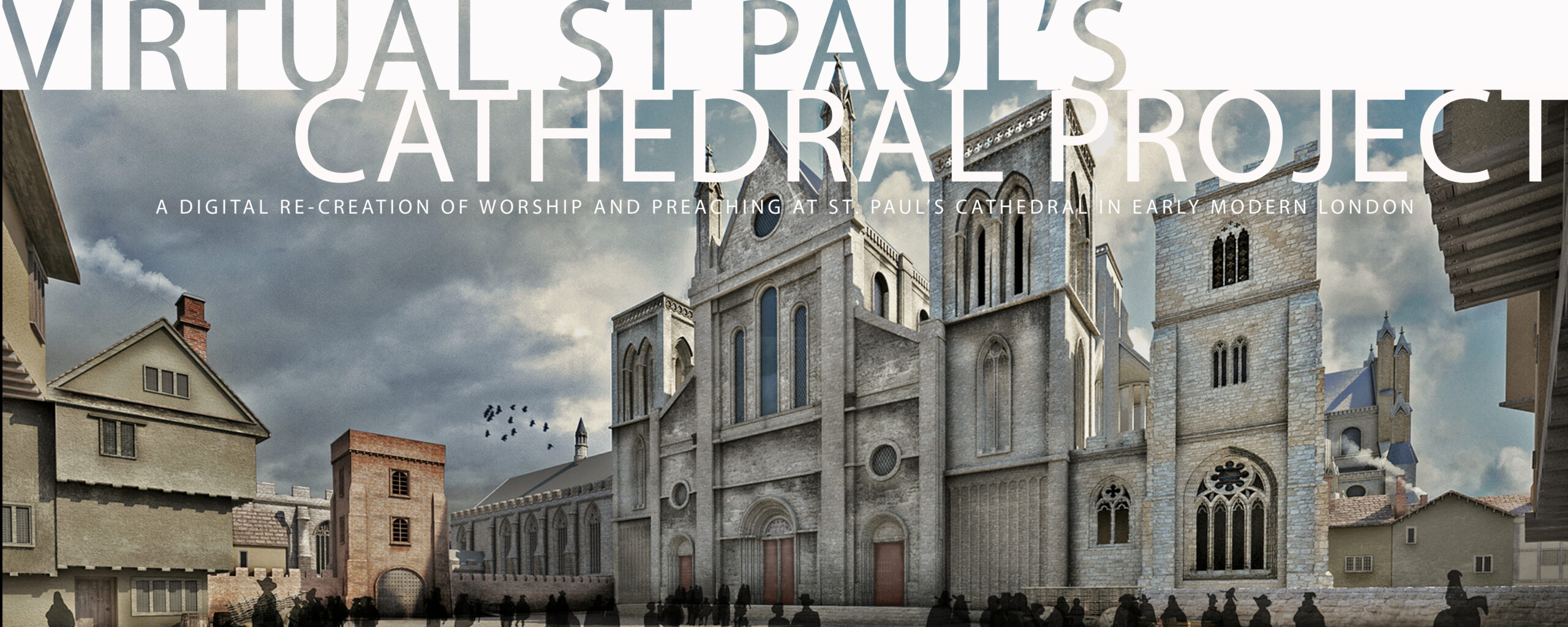

The purpose of the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project — and its companion project, the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project –– is to make available in real time the experience of daily worship in the Church of England in the early seventeenth century. The chief function of a cathedral in early modern England was to maintain the daily round of worship services according to the use of the Book of Common Prayer, as an end in itself, as the material embodiment of the diocese at prayer, and as a model of devotion and practice for other churches in the diocese.

As a result, we will be able to glimpse how the daily worship of the post-Reformation Church of England, as scripted by the BCP, both informed congregations as to who they were as the church, the Body of Christ on Earth, and also formed them as Christian community, doing the work of “living in love and charity with their neighbors.” The worship of the Church of England provided the context for all religious reflection, preaching, and practice. Now, useers of this site can experience that liturgical day, learn how it was constructed, what was involved in performing it, and what messages were learned through its use.

St Paul’s Cathedral thus serves as an example, a standard, and a proxy for parish churches in their own embodiment of this prescribed round of services. The style of cathedral worship was distinctive, with its use of organ and a professional choir of men and boys, but the services themselves were the same. While the continued existence of cathedrals in the post-Reformation Church of England has puzzled many historians, yet their presence as physical embodiments of episcopal governance and their function as symbols of the diocese at prayer seems entirely understandable for a Church resolved to be, or out of necessity came to be, a Church pragmatic in its determination to accommodate a full range of spiritualities, from, in Peter White’s words, “conscientious Catholics at one extreme and Protestants desirous of further reformation at the other.” [1]In Predestination, policy, and polemic, p. 92.

In recreating the experience of early modern worship, we emphasize the importance of understanding the practice of corporate worship in the post-Reformation Church of England, with its set organization of services, its prescribed rotation of Psalms and readings from scripture, its observation of the seasons of the Church Year, its practice of the sacraments of Baptism and Holy Communion, and its providing the liturgical context for the preaching of sermons.

This round of services included Divine Service, the services of Morning and Evening Prayer “daily throughout the yeere.” This practice was the foundation of public worship; in addition to acts of confession and absolution for sins as well as prayers of intercession and thanksgiving, it provided the liturgical framework for bringing the majority of scripture into the public soundscape, providing for repetition of the entire Book of Psalms once a month, the majority of the Old Testament once a year, and the majority of the New Testament three times a year.

To these Daily Offices was added the Great Litany “upon Sundayes, Wednesdayes, and Fridayes and at other times when it shalbe commanded by the Ordinarie” (the Bishop of the Diocese). Holy Communion was celebrated on Sundays and Holy Days throughout the year. The Calendar of Holy Days at this point in the life of the Church of England included, in addition to Sundays, 33 Holy Days, including the Feast Days of 21 Saints (all biblical figures) and 12 major festival days (such as Christmas, Easter, Whitsunday, Trinity Sunday, and All Saints Day).

All these special days were contained within the great cycle of seasons in the Christian Year, beginning with Advent (the four Sundays before Christmas), continuing with Christmas (twelve days) and Epiphany (January 6th until Ash Wednesday), moving on to Lent (the 40 days, plus Sundays, between Ash Wednesday and Easter (the days between Easter Day and Trinity Sunday), then shifting from remembrance of Jesus’ life to the life of the Church with Trinity Sunday and the Sundays after Trinity.

Definitions of Christianity that focus chiefly on theological texts privilege the cognitive meaning-making of the faithful, thus isolating the faith in the work of the study, of the scholar or theologian alone, in the process of thinking and writing. So much of the scholarship about post-Reformation England attends only to the arguments of the learned about doctrine and belief while ignoring the daily formation for Christian living provided by, and informed by, the performed language of the Book of Common Prayer and the biblical texts it brings to people’s attention on a daily basis.

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project therefore enables us to understand and appreciate how the rites for public worship scripted by the Book of Common Prayer provided the context for the English Reformation’s renewal of interest in preaching. The cycle of rites scripted by the Book of Common Prayer and their attendant reading of assigned Lessons from the Bible. The Prayer Book’s organization of public worship, with its structured progress of scriptural readings, set prayers and canticles, and sacramental rites for incorporation into and strengthening of the Christian community, created the background for preaching, from the perspective both of clergy and of layfolk.

A sermon was called for in the rite of Holy Communion, regardless of whether or not the service proceeded beyond the Liturgy of the Word. Sermons could be attached to other services like Evening Prayer. Even sermons that were delivered extra-liturgically — like the regular sermons at Paul’s Cross outside St Paul’s Cathedral — were delivered in the context of expectations among layfolk that gatherings for worship would be structured formally, on the model of Prayer Book rites. So we see in John Gipkin’s painting of a Paul’s Cross sermon in progress that the preacher for the day is vested as he would have been for services in the Cathedral’s Choir. The Cathedral’s verger stands behind the Preaching Station in the formal attire of his office, having led a procession from the Cathedral to the Preaching Station before the opening of the event; now he stands ready to lead another procession back to the Cathedral when the sermon is over.

For clergy, as well as laity who followed the Prayer Book’s discipline of reading the Daily Offices, the texts of the Bible, as they unfolded day by day inevitably informed their reflection on scripture and on the faith of the Church. This immersion in the ongoing process of biblical readings sometimes is reflected in sermons and devotional writings, for which practice John Donne provides some examples. In his Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, Donne repeatedly makes reference to the Book of Ecclesiasticus, a relatively minor biblical text included in the Apocrypha section of the Hebrew Bible, thus an unlikely source of comfort for someone dealing with a major illness. Yet it happened to be one of the sources for daily scripture readings at Morning and Evening Prayer precisely during the time we believe Donne was ill in the late fall of 1623. The specific Psalms Donne was called on to read daily as holder of the Prebendary of Chiswick (Psalms 62 – 66) became the focus of several of his sermons. But even when direct reference to the Lessons for the Day do not appear in a sermon, they form part of the context for the preacher’s reflection on his subject and hence are worthy of inclusion in scholarly consideration of a sermon when we know the date of delivery and may indeed help with dating when we do not.

Historians of the English Reformation often argue about beliefs (predestination, etc.) that limit the numbers of the redeemed, while the Book of Common Prayer, in all its 16th and 17th century versions, performs the creation and evolution of a worshipping community from the perspective of a hypothetical universalism. Everyone born in England after the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) was required to be baptized within a few days of birth at the local parish church, to attend church on Sundays, and to receive the bread and wine of Holy Communion at least three times a year, and always on Easter Sunday. So all were told that their sins were forgiven, that they were enabled to “lead a new life, walking from henceforth in [God’s] holy ways,” that they were “very members incorporate in the mystical Body of Christ.” that they were “heirs through faith of [God’s] holy kingdom.”

Historians also take sides in on the question of whether or not the English Reformation should have taken place at all, since it was, at least initially, a Reformation from the top down, motivated by Henry VIII’s desire to divorce his first wife rather than a popular movement, rising from the bottom up and embraced from the beginning by the general populace. On the other hand, historians who accept the significance of the English Reformation tend to share the perspective of the more radical English Protestants that the English Reformation did not turn out to create the kind of church it should have, that it should instead have followed the example of the Reformed churches in Zurich and Geneva in abolishing the episcopate, the use of set prayers as contained in the Book of Common Prayer, and other traces of what was understood to be the Medieval Church.

Nonetheless, as we will see, the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion (1559) reaffirmed the structure and the enabling texts of the Edwardian Reformation, most of all seeking national unity in religious belief and practice. Cranmer said that the Book of Common Prayer would provide “one use,” which enabled all Englishfolk to pray, as William Harrison puts it, in the unity of one voice, enabling “the whole congregation at one instant pour[s] out their petitions unto the living God for the whole estate of His church in most earnest and fervent manner.”

The vast majority of participants in the liturgical life of the Church of England learned about their faith through corporate practice, through hearing and reciting and reflecting on the words of the liturgies they encountered in corporate worship. Our emphasis on worship in this Project derives from our belief that liturgical worship’s mix of the fixed, the ephemeral, and the varied is essential to the character of public worship, hence is central to the creation of religious identity. John Donne says, in the Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, that he knows God is present to the faithful in Church, where scripture is read, the ancient Creeds are repeated, the Gospel is preached, the Sacraments performed, and all done decently and in good order. Donne knows God is there, where the people are gathered, in Church; God’s presence in Donne’s bedroom, where he is confined by his sickness, is, for much of the Devotions, a matter of speculation.

In taking this approach, we affirm what is of course at the heart of what it means to be Christian from the earliest days, by participation in the gathering of the Church’s members, continuing “the apostles’ teaching, the breaking of bread, and the prayers.” In other words, we attend to the significance of Cranmer’s emphasis on the Book of Common Prayer as a unifying force in the development of a national religious identity.

Our goals for this project have included exploring how the liturgies and sermons that survive for us in books and manuscripts served for Donne and his contemporaries as scripts for performance that achieve their true identity when enacted by clergy and their congregations in particular places on specific occasions, thus recovering interactive and performative elements in English worship. Our development of an interface that gives us access to Donne’s preaching and its liturgical context as events helps us understand more fully his own personal transitions as lived events, as he came to recognize that “no man is an island,” that we are all involved with each other in a larger vision of humanity.

References

| ↑1 | In Predestination, policy, and polemic, p. 92. |

|---|