As Christian Steer has put it, “St Paul’s was a mausoleum of the dead.” [1] Christian Steer. “The Canons of St Paul’s and their Brasses.” Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society (2016), 233. St Paul’s Cathedral and the Churchyard around it served as graveyards for the nobility and the commonality throughout the Middle Ages and into the early modern period. Any Londoner could request to be buried in Paul’s Churchyard, chiefly in the northeast corner of the Churchyard. During the early modern period, Londoners sometimes complained about the gravediggers leaving newly dug graves open when night fell, creating a hazard for Londoners cutting across the Churchyard in the dark.

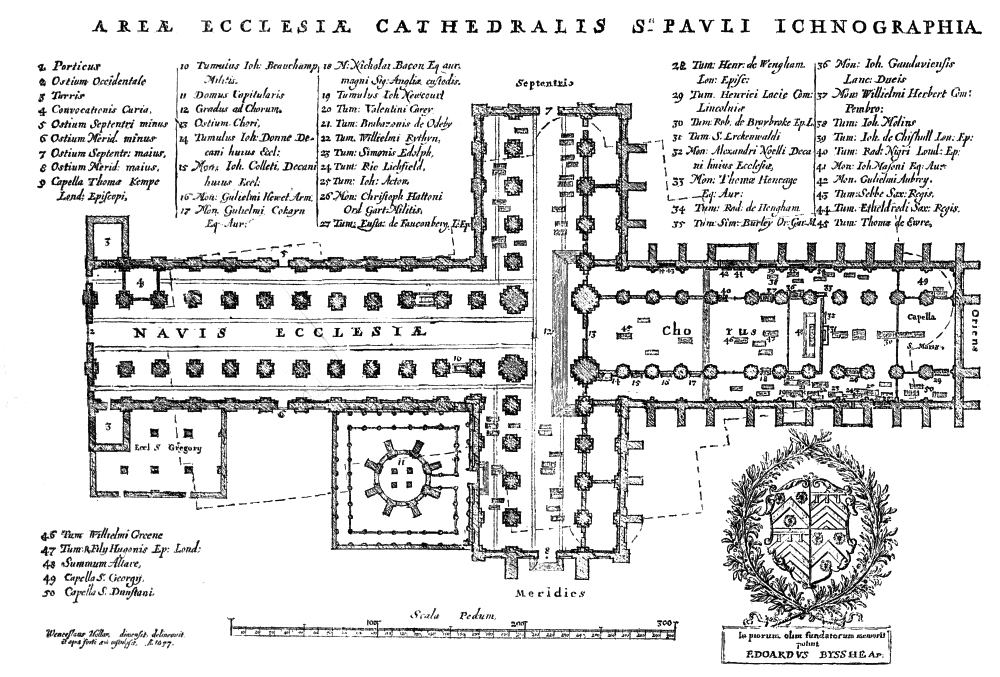

Medieval St Paul’s Cathedal contained many statues and shrines to the saints, as well as side altars and the central high altar, all of which were destroyed in the iconoclastic phase of the English Reformation. Monumental brasses crowded the floor, making it, in Steer’s terms, “a spectacular floor space,” consisting of “a rich series of floor slabs, series of floor slabs, either incised or of Lombardic brass lettering, rmembering long dead canons.” [2]Steer, 234.Tombs of the nobility and senior clergy previously buried in St Paul’s survived, as did the practice of burying folks there and erecting monuments to them.

In some cases, such as that of Sir Philip Sidney, the body was interred but no monument was erected. The Dutch traveler Abraham Booth visited St Paul’s in the 1620s and wrote this description of Sidney’s burial site in his journal. [3]For Booth’s Journal, go here: <https://www.uu.nl/en/utrecht-university-library-special-collections/collections/manuscripts/modern-manuscripts/the-description-of-england-by-abraham-booth>. This translation from Booth’s account of his visit to St Paul’s, is courtesy the distinguished Shakespearian actor William Sutton, who appears in the role of a Canon of St Paul’s in our worship service recordings).

Behind the choir hangs a tapestry scene with the epitaph for Sir Philip Sidney without any tomb; remarkable, that the noble class, of which England is so prized, set up no statelier resting place for his remains. The epitaph sounds like this:

England, Netherlant, the Heavens and the Arts,

The soulders, and the World have made six parts

Of the noble Sidney: for none will suppose

That a smal heape of stones can Sidney enclose.

His body hath England, for she it bred;

Netherland his bloud, in her defence shed;

The Heavens have his soul, the Arts his fame;

The soldiers the griefe, the World his good name.

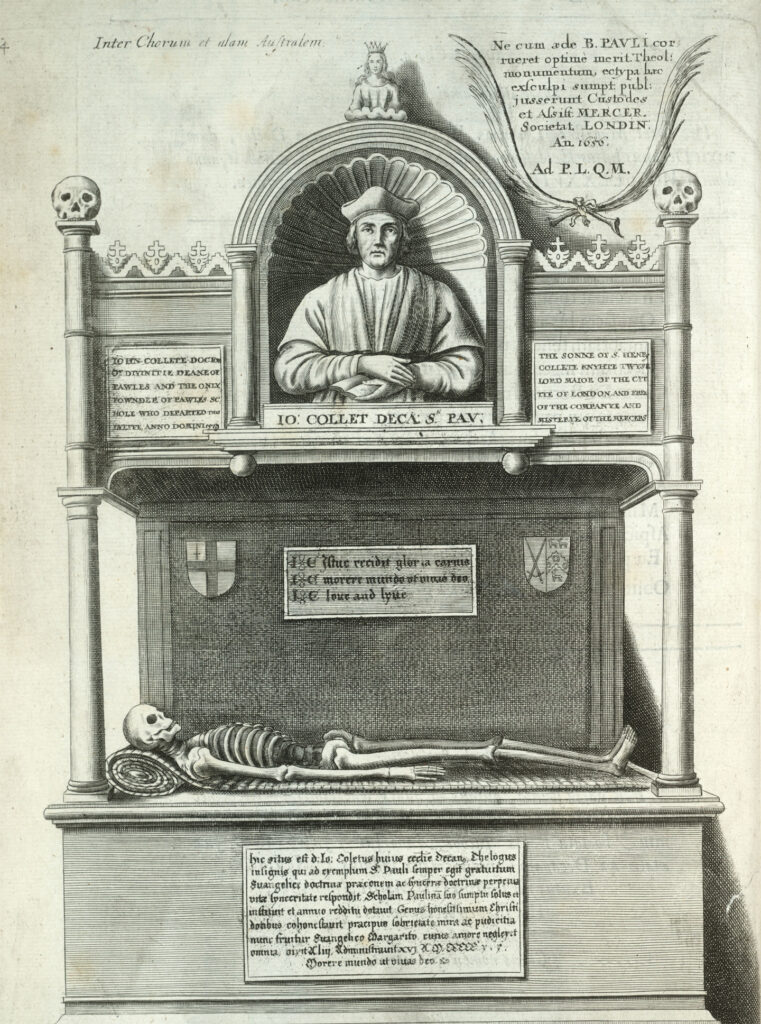

Space inside the Cathedral was generally reserved for members of the nobility or for senior clergy. John Donne was buried inside the Cathedral when he died in 1631, in the south aisle of the Choir adjacent to the monument to John Colet, Dean of St Paul’s from 1505 to 1519. Some folks were buried in the Cathedral’s floor, scattered through the Nave and into the Choir. Others were buried in tombs constructed along the sides and aisles of the Nave and Choir.

Most of the gravesites inside the Cathedral were marked by stone slabs in the floor, usually with an inscription or a monumental brass. Hollar depicts a number of these gravestones in his engravings for William Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658).

Members of the nobility as well as some wealthier or more prominent people who were buried in St Paul’s were recognized by the construction of substantial monuments to their memory. Hollar depicted a number of the free-standing tombs and funeral monuments as well as other burial or memorial sites that were located against the outer walls of the Cathedral. With the assistance of Hannah Faux and Juan Jose Fuldain of the Museum of London Archaeology, John Schofield has developed three-dimensional models of some of these monuments, which are included in our Visual Model.

On this page of the website we have brought together copies of Hollar’s engravings of some of these monuments, together with images of Schofield’s models and (when available) renderings of the Visual Model to suggest the appearance of these monuments in their original setting.

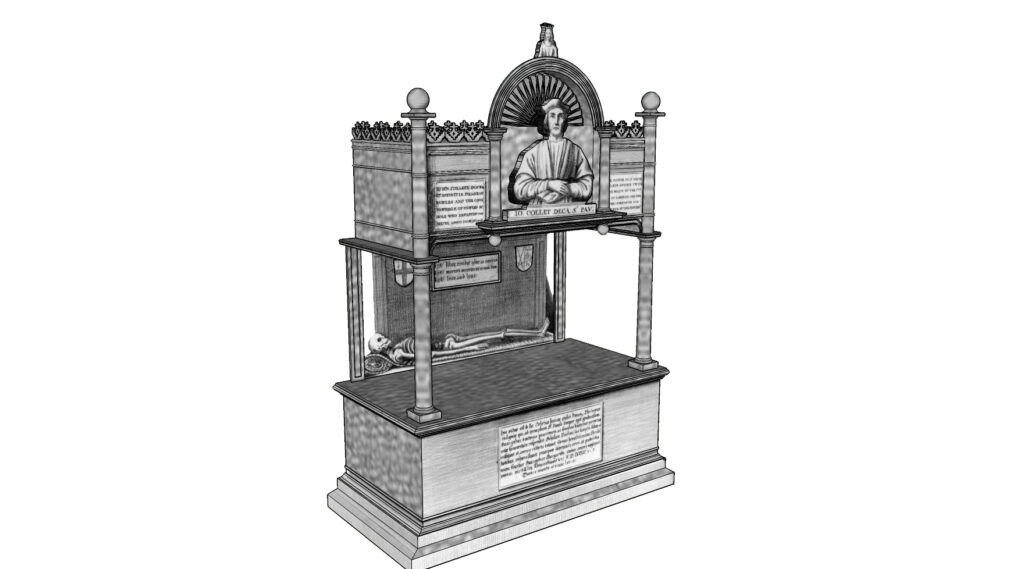

The first of these is the Monument of John Colet, Dean of St Paul’s from 1505 to 1519. Colet’s monument was located in the South Aisle of the Choir, facing southward behind the Choir stalls. Colet’s monument would be joined by John Donne’s monument in 1631, which was located one bay westward of the site of Colet’s monument.

Monument to John Colet. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to John Colet. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

Monument to John Colet. Rendering by Grey Isley

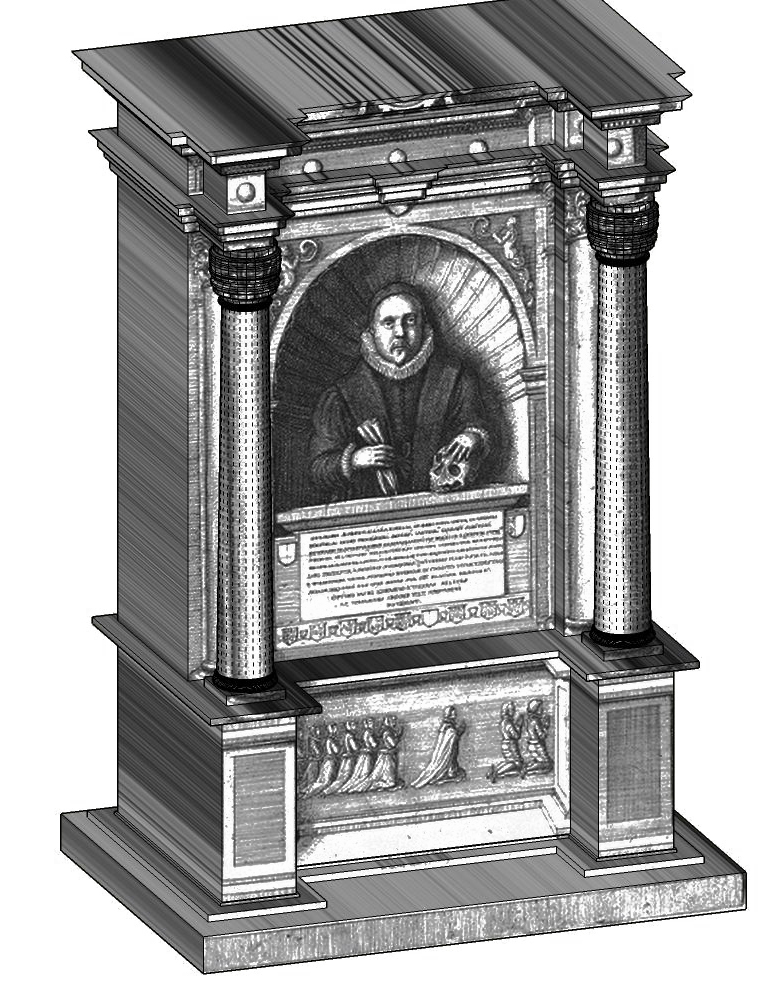

Below is the monument to William Aubrey, which was located in the Choir against the North Wall.

Monument to William Aubrey. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to William Aubrey. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

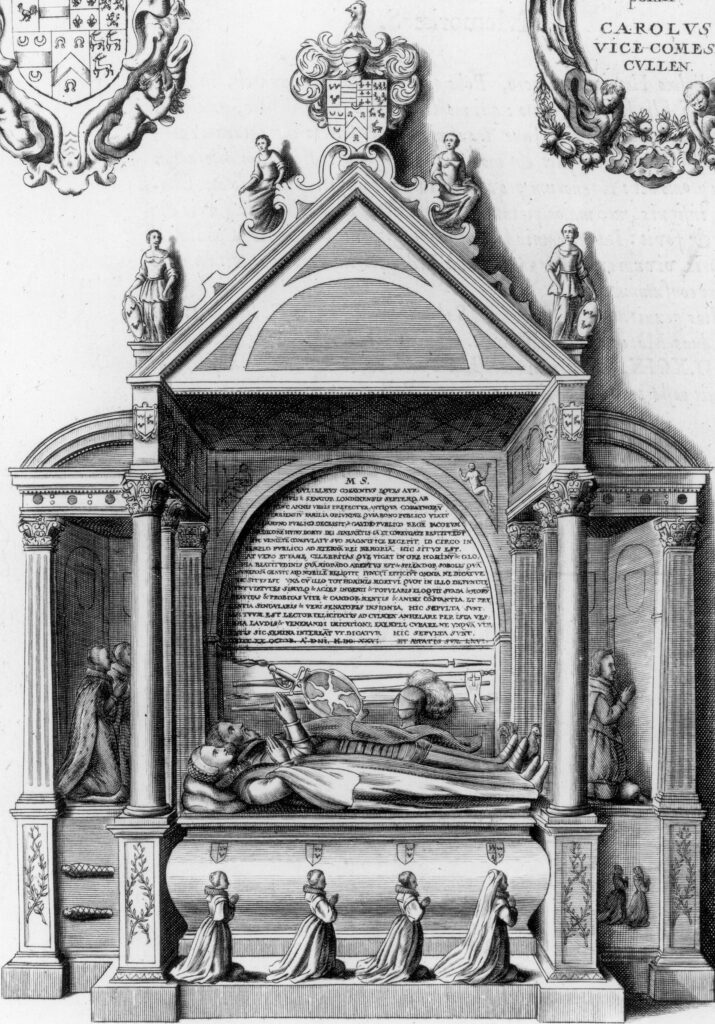

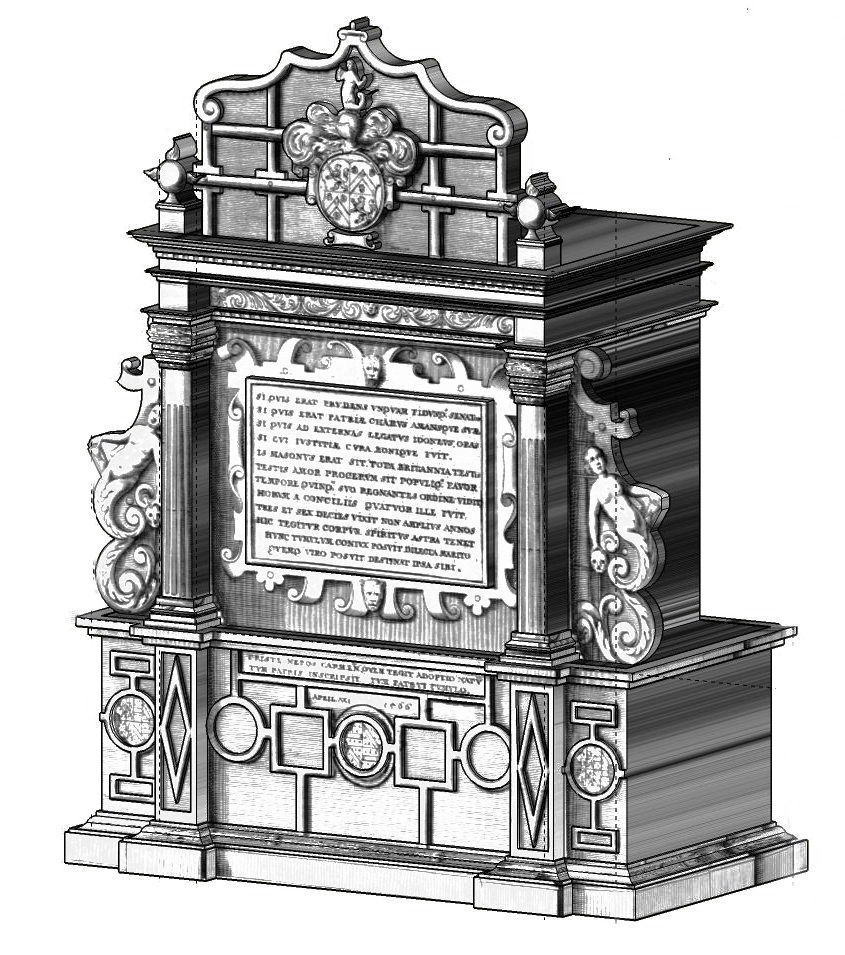

Monument to Nicholas Bacon. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to Nicholas Bacon. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

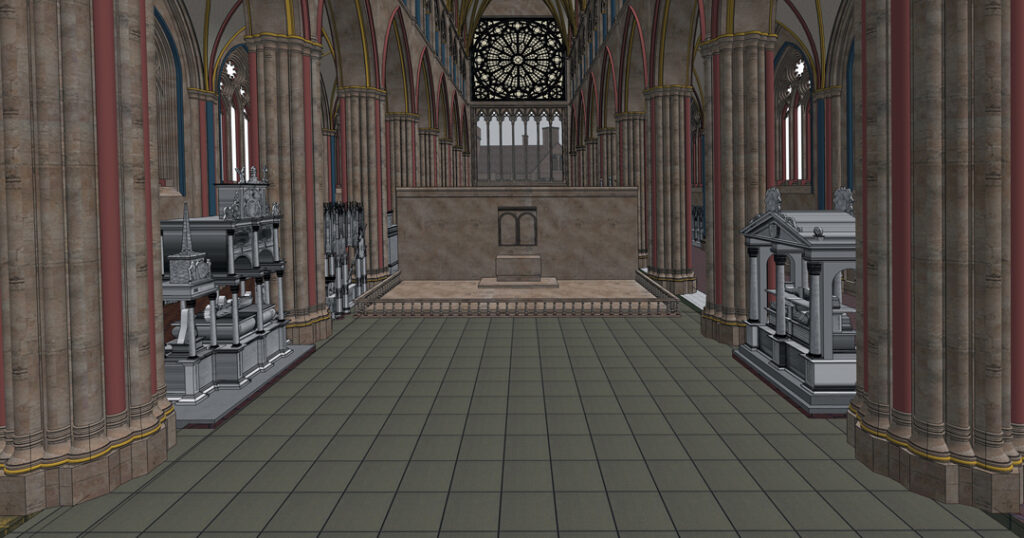

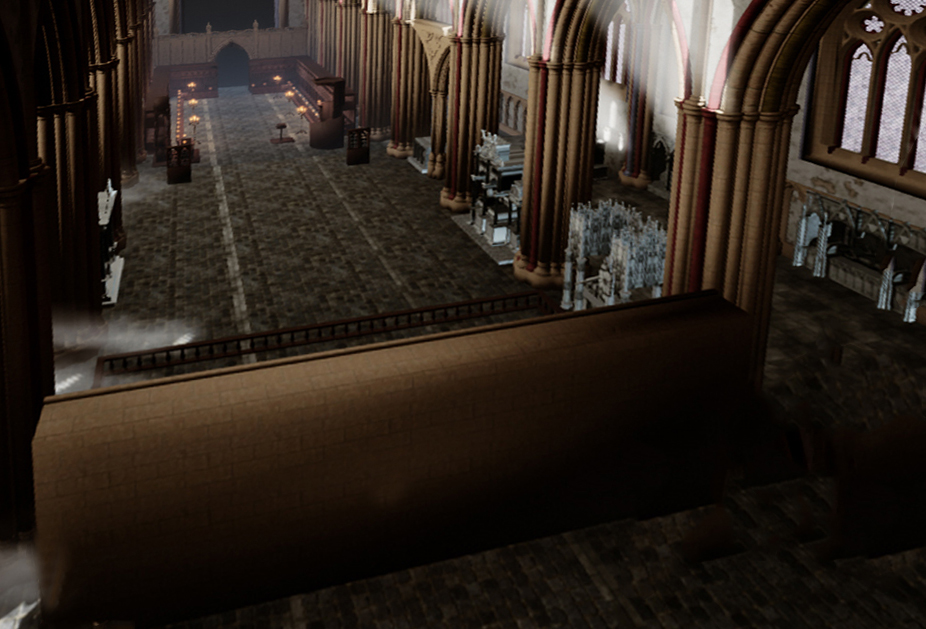

Nicholas Bacon’s monument was located in the Choir, and is shown in the image of the Choir below.

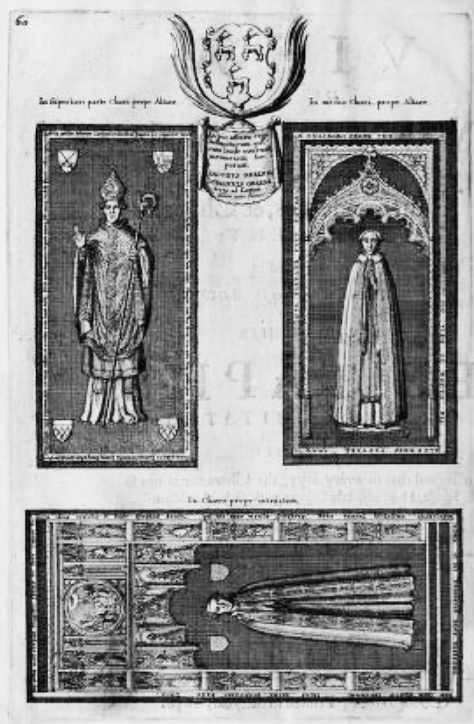

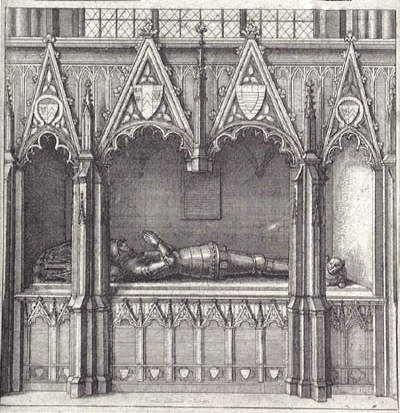

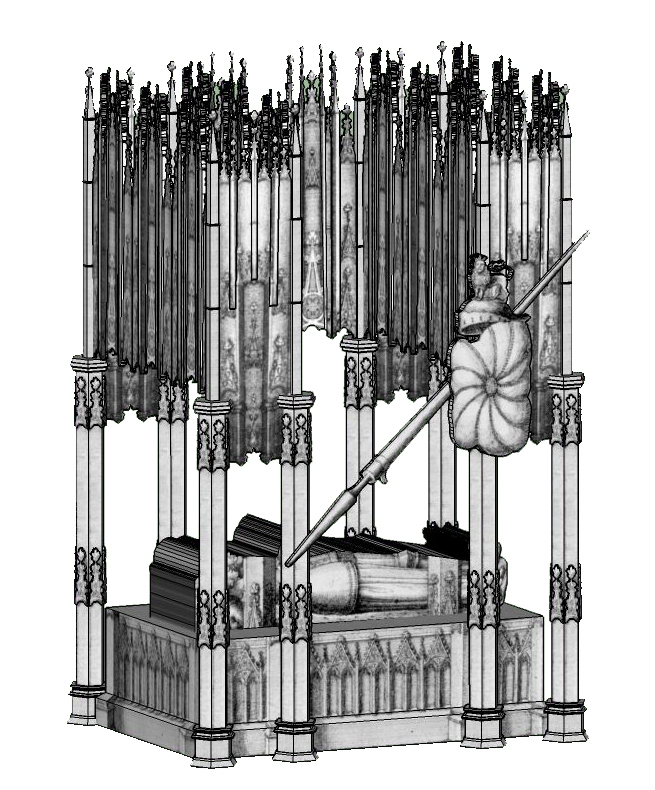

Next we have the monument to Sir Richard Burley, which was located in the Choir, near the Altar.

Monument to Sir Richard Burley. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

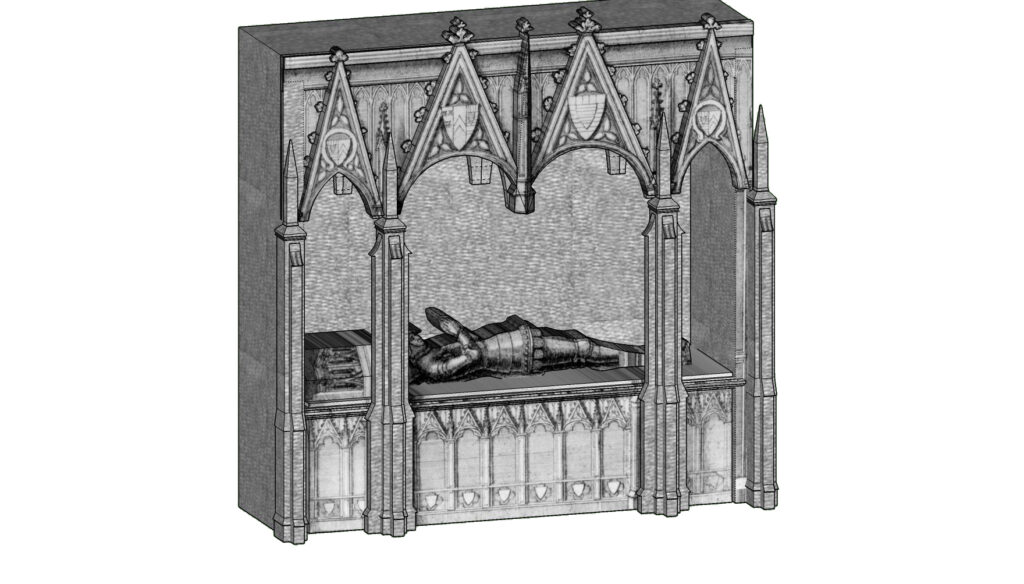

Monument for Sir Richard Burley. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

.

Monument to Sir William Cockayn. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to Sir William Cockayn. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

The Monument to Sir William Cockayn was located in the Choir, immediately behind the Bishop’s Throne.

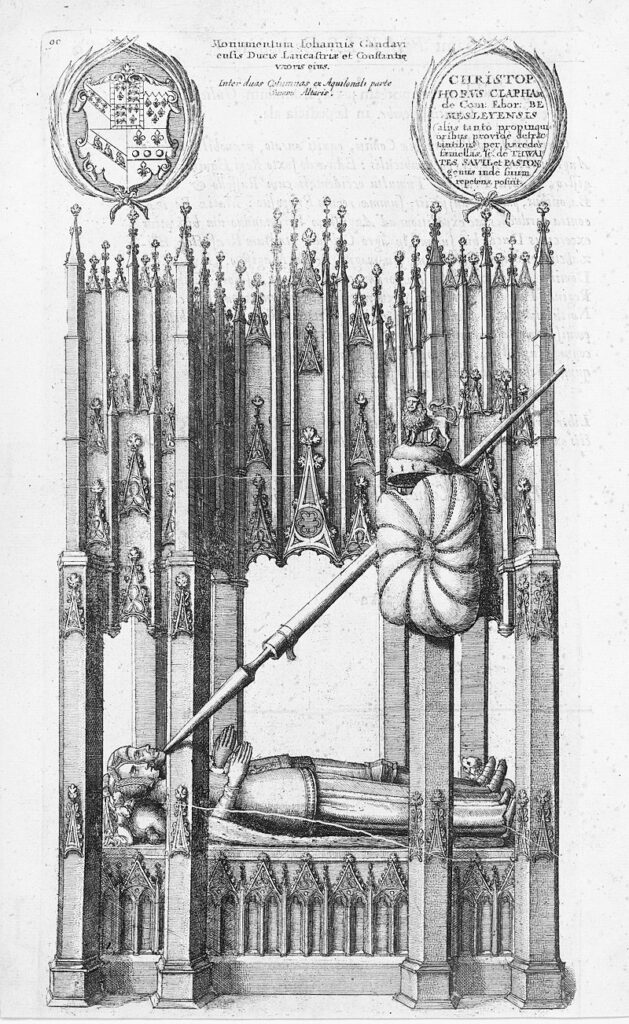

Monument to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

The monument to John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, was located in the Choir, near the Altar, and is visible in the image above.

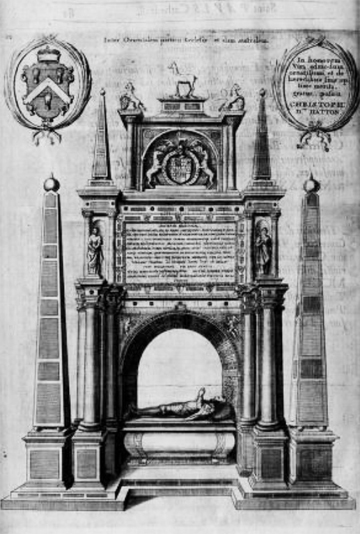

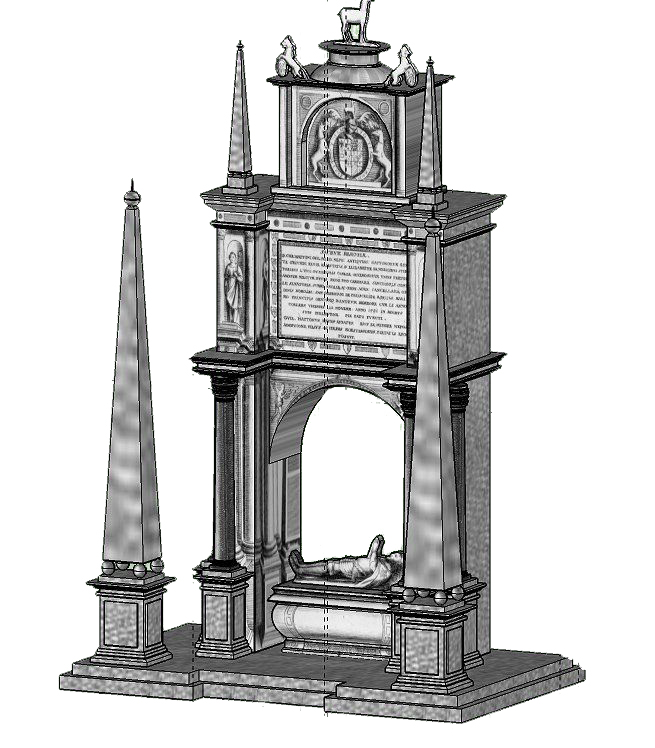

Monument to Sir Christopher Hatton. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to Sir Christopher Hatton. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

Sir Christopher Hatton’s monument was located the south aisle of the Choir.

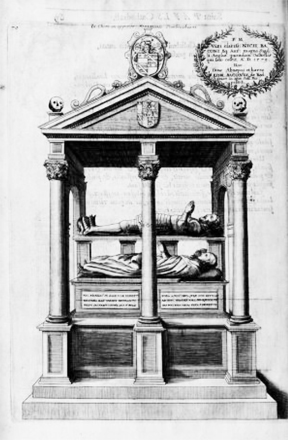

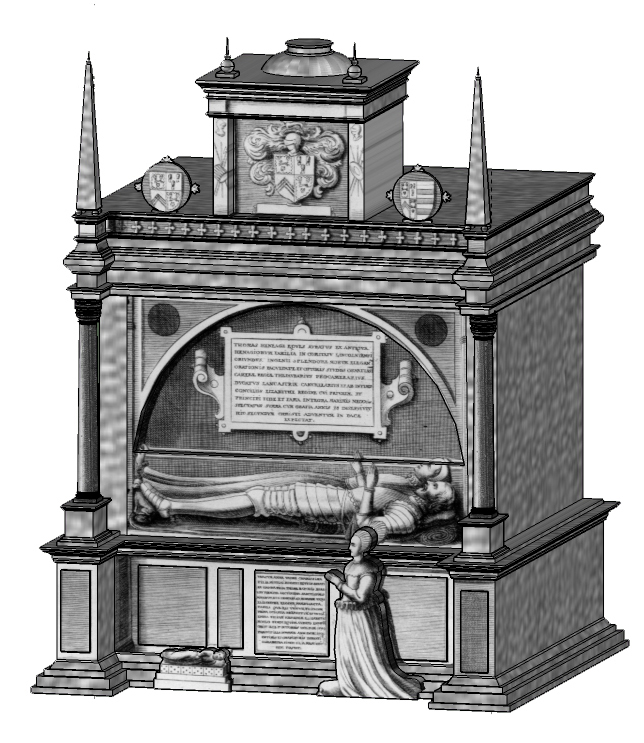

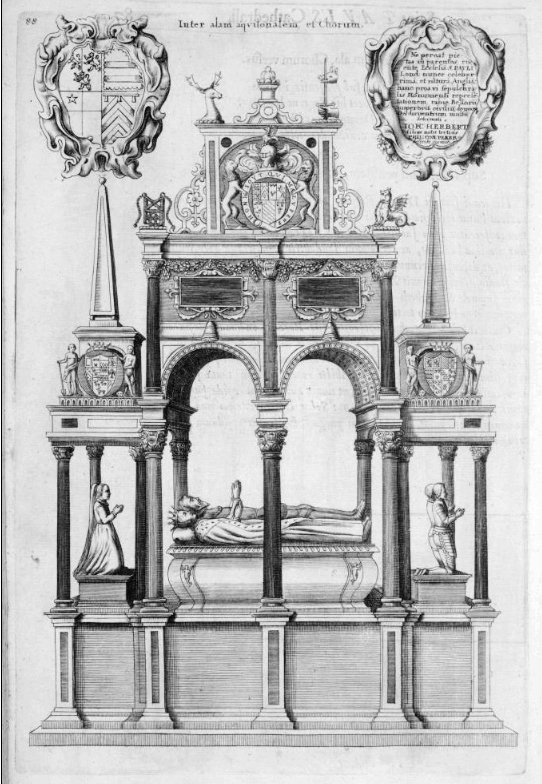

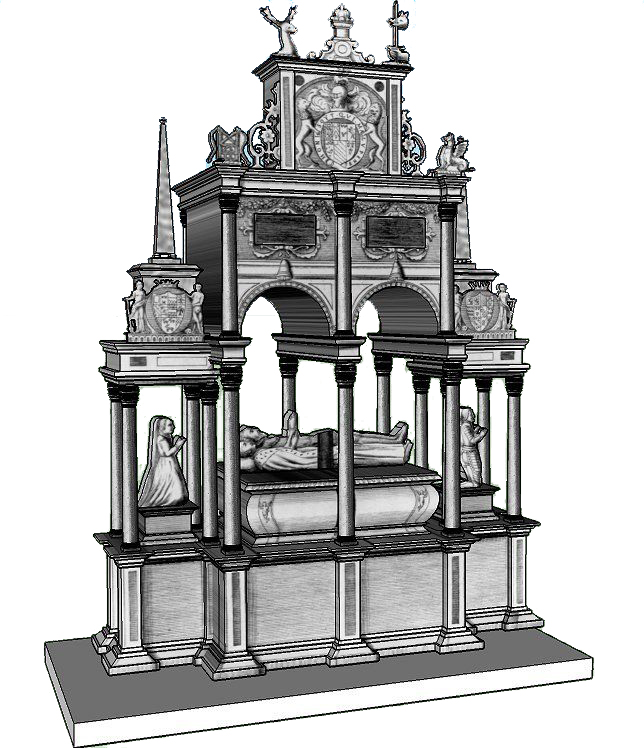

Monument to Sir Thomas Heneage and his wife. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to Sir Thomas Heneage and his wife. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

The monument to Sir Thomas Heneage and his wife was located in the north aisle of the Choir, near the Altar. Part of the statue of Heneage, shown here on his monument, survived the Great Fire and is now on view in the basement of Wren’s St Paul’s.

Sir Thomas Heneage. Image courtesy Wikimedia Comons.

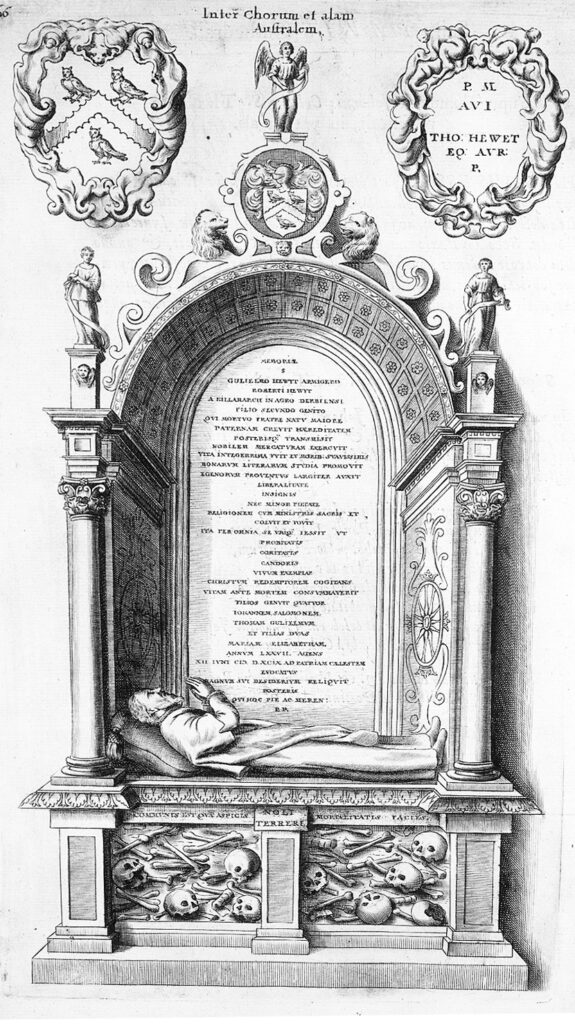

Monument to William Hewett. Engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, from William Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Monument to William Hewett. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

The monument to William Hewitt was located in the south aisle of the Choir, behind the Choir stalls, facing south.

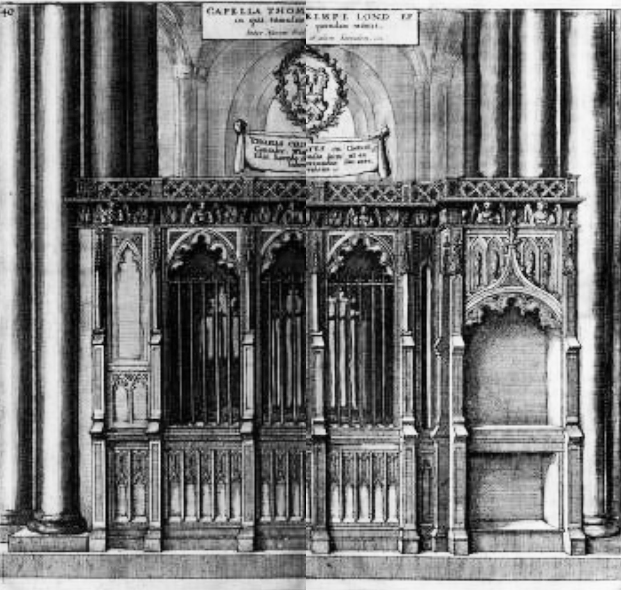

Bishop Robert Kempe, his Tomb. Engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar. From Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Bishop Robert Kempe, his Tomb. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Bishop Kempe’s tomb was located in the Nave just west of the Choir Screen, and can be seen in the images above and below.

Sir John Mason’s tomb was located near Aubrey’s, in the Choir against the North Wall.

Sir John Mason. Engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar. From Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Sir John Mason. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

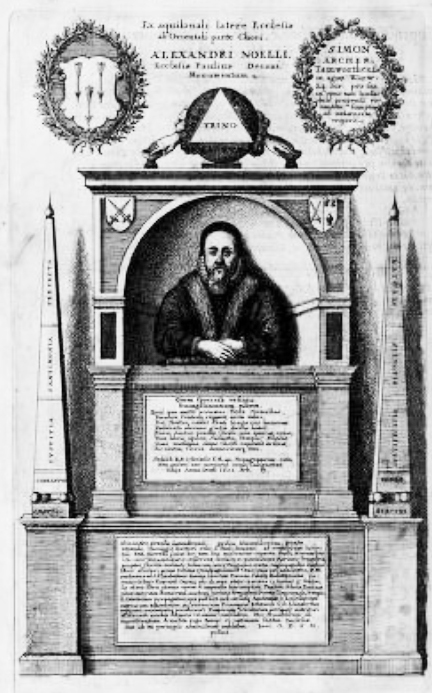

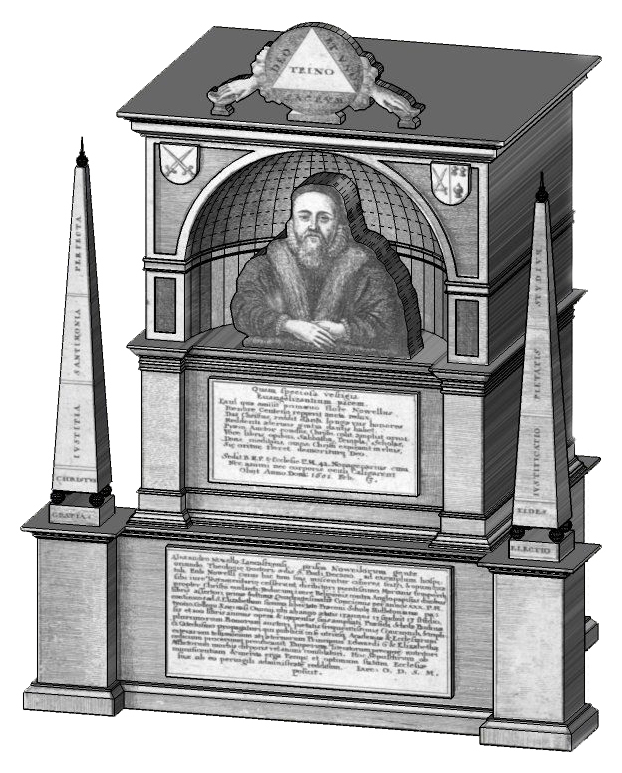

Alexander Nowell’s monument was located in the east end of the Choir, on the east side of the partition that, on the west side, provided a backdrop for St Paul’s Altar.

Alexander Nowell. Engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar. From Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Alexander Nowell. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the South Aisle of the Choir, looking east. Model created by Grey Isley.

The monument to the Earl of Pembroke was located in the North Aisle of the Choir, near the Altar, and is visible to the left side of the image above.

The Earl of Pembroke. Engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar. From Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

The Earl of Pembroke. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

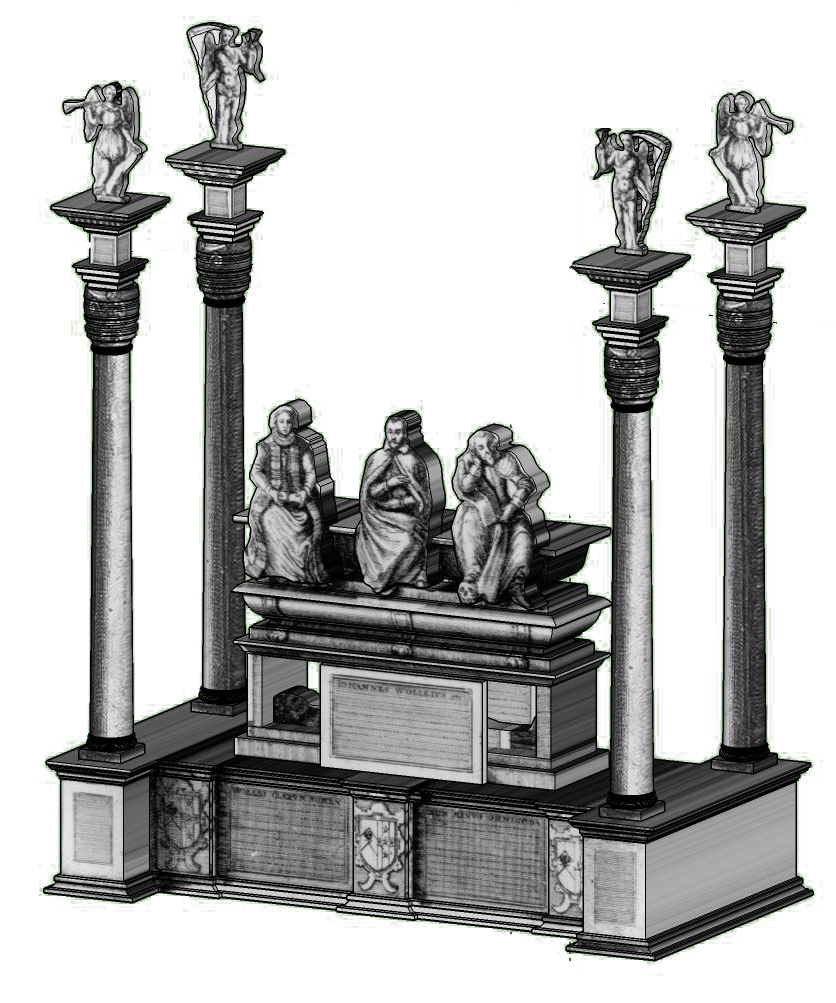

Nearby was the monument to Sir John Wolley and his wife Elizabeth. Their effigies also survived the Great Fire and are on view in the basementof Wren’s St Paul’s. See a photo of Elizabeth Wolley’s effegy, above.

Sir John Wolley, Wife, Son. Engraved by Wenceslaus Hollar. From Dugdale, History of St Paul’s Cathedral. Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

Sir John Wolley, Wife, Son. Model by Juan Jose Fuldain.

A Look into the Future

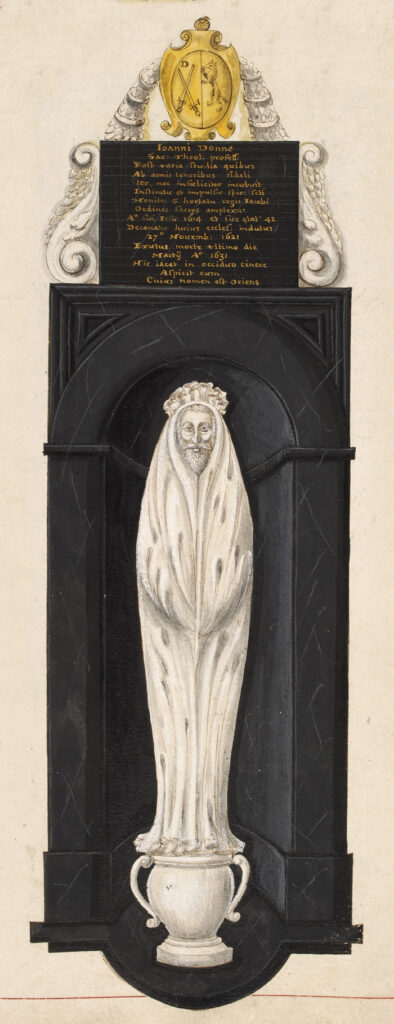

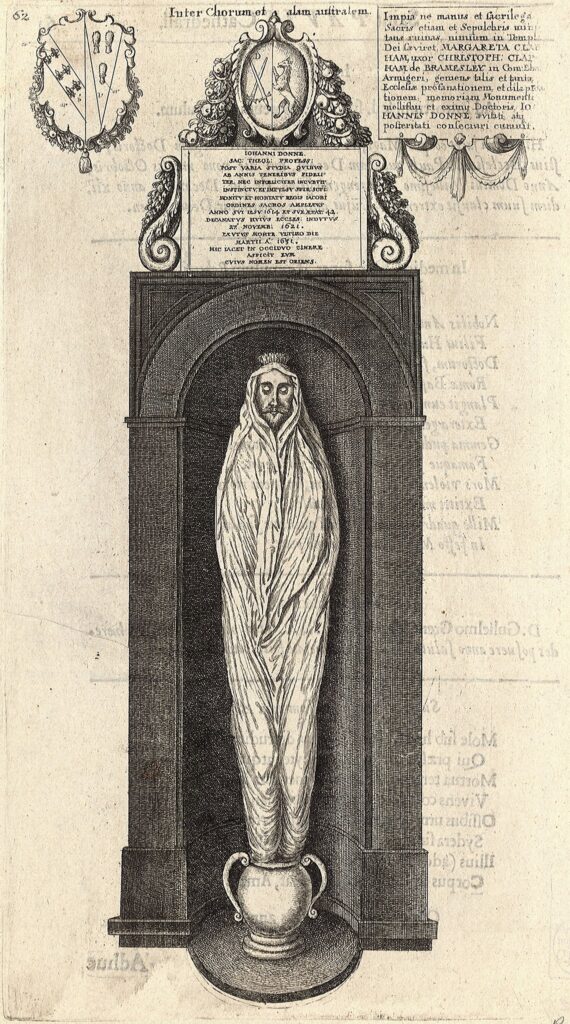

John Donne, before his death on 31 March 1631, posed in his winding sheet for a life drawing which became the basis for the monument to him in St Paul’s, erected just west of the monument to John Colet. Above the statue is a Latin epigraph, which he probably composed (see text below). Above the epigraph is Donne’s seal as Dean of the Cathedral, showing on the left the crossed swords of St Paul, with the letter “D” for Decanus, and on the right a heraldic wolf.

The presence of the wolf derives from the fact that Donne believed that he was related through his father to the Dwn family of Kidwelly, in Carmarthenshire. Donne used the arms of that family on his earliest portrait, painted in 1591, as well as on one of his seals, and, again, here, on his monument. The arms of the Dwn family include the figure of a wolf rearing up, as well as a crest of snakes bound in a sheaf (see Donne’s poem “A Sheaf of Snakes,” written for George Herbert for Donne’s use of that element in his supposed family coat of arms).

The statue in St Paul’s was said by Izaac Walton, Donne’s first biographer, to show Donne at the moment of his resurrection, at the moment, anticipated in Job 19 vs. 27, in which his body is rising but his eyes have not yet opened to behold his savior. The statue itself was one of the few monuments in St Paul’s to survive the Great Fire; it was stored in the basement of the Wren building until, in the latter part of the 19th century, it was reinstalled in a reconstruction of the original niche for it shown in Hollar’s engraving of the monument (see image on the left, below), except that, in the reconstruction, the heraldic wolf has been turned into a rearing horse and the text of the epigraph has been rearranged from its original urn-shape configuration into a rectangular box.

John Donne Memorial, drawn by William Sedgewick (1641)

John Donne Memorial, engraved by Wenseslaus Hollar (1658). Image courtesy the Wenseslaus Hollar Digital Collection, University of Toronto.

John Donne Memorial, Today

Donne’s epigraph reads,

IOHANNI DONNE.

SAC: THEOL: PROFESS:

POST VARIA STVDIA QVIBVS

AB ANNIS TENERIBVS FIDELI=

TER, NEC INFŒLICITER INCVBVIT

INSTINCTV ET IMPVLSV SPIR: SCTI:

MONITV ET HORTATV REGIS IACOBI

ORDINES SACROS AMPLEXVS

ANNO SVI IESV 1614 ET SVAE ÆTAT. 42.

DECANATVS HVIVS ECCLES: INDVTVS

27° NOVEMB: 1621.

EXVTVS MORTE VLTIMO DIE

MARTII A. 1631.

HIC IACET IN OCCIDVO CINERE

ASPICIT EVM

CVIVS NOMEN EST ORIENS.

In the 19th century translation by Francis Wrangham, this reads,

JOHN DONNE,

Doctor of Divinity,

after various studies, pursued by him from his earliest years

with assiduity and not without success,

entered into Holy Orders,

under the influence and impulse of the Divine Spirit

and by the advice and exhortation of King James,

in the year of his Savior 2614, and of his own age 42.

Having been invested with the Deanery of this Church,

November 27, 1621,

he was stripped of it by Death on the last day of March 1631:

and here, though set in dust, he beholdeth Him

Whose name is the Rising.

References

| ↑1 | Christian Steer. “The Canons of St Paul’s and their Brasses.” Transactions of the Monumental Brass Society (2016), 233. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Steer, 234. |

| ↑3 | For Booth’s Journal, go here: <https://www.uu.nl/en/utrecht-university-library-special-collections/collections/manuscripts/modern-manuscripts/the-description-of-england-by-abraham-booth>. |