The Dimensions

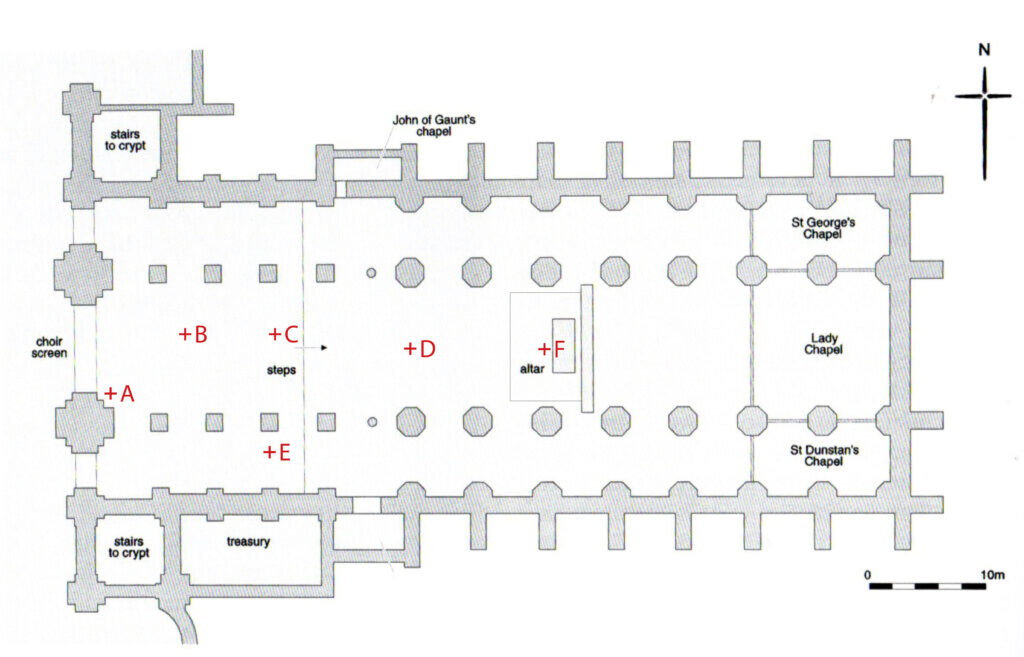

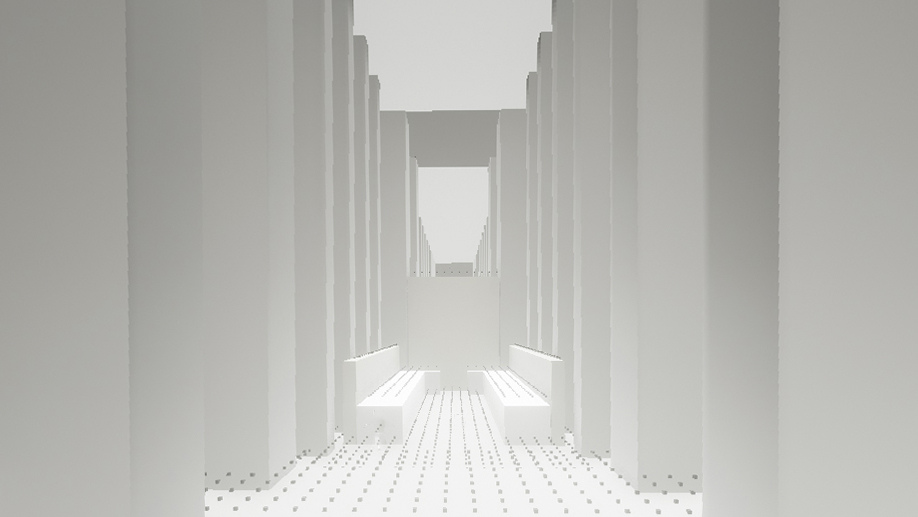

While our acoustic model of St Paul’s Cathedral includes the entire building, our chief focus has been on the Choir of the Cathedral, where worship services were conducted. The basic shape of the Choir was a rectangle measuring roughly 240 feet from the Choir Screen to the East Wall and 84 feet from the north wall to the south wall. The center section (between the columns) was about 42 feet. The length of the space occupied by the stalls was about 60 feet from the Choir screen to the bottom of the steps leading up to the altar platform, then about 82 feet from the top of the steps to the altar itself. The distance from the partition behind the altar to the East Wall was about an additional 85 feet.

Unlike the acoustic model we created for the Paul’s Cross Project, the model for the Cathedral Project includes a ceiling over the Choir and also a change in the height of the ceiling relative to the floor, due to the steps that take one up a couple of feet or so east of the Choir Stalls. The height of the ceiling at its highest point above the western part of the Choir (the area with the stalls) was about 90 feet; the height of the ceiling above the floor east of the steps leading from the stalls to the area in front of the altar was about 86.5 feet.

An acoustic model is a model of the space within the place one is modeling, rendered in its most basic geometric forms. To this model one adds information about the sound-handling properties of the materials out of which the forms inside the model were constructed, in this case, chiefly stone and wood. In a space, sound moves in wave forms that proceed away from the sound source with predictable attenuation of volume, until a sound wave strikes something. Then, depending on the form of the object and the materials out of which the object is made, the sound wave is to some degree either absorbed, reflected, or dispersed. The work of acoustic modeling software is to modify sound waves so as to create the experience of hearing sounds in the space one is modeling.

EXPLORING THE SOUNDS OF WORSHIP

To sample differences in the sound as it varies from listening position to listening position, click on the image below to play a 2 minute video, taken from the service of Easter Matins. The video switches from one listening position to another for both spoken and choral sections of the recording.

EXPLORE TYPES OF SOUND

THE BELL

The tolling of the bell is an important part of worship because it serves to signal the hour, to call worshippers together or to attention, and to mark the passage of time during the service itself, helping worshippers to place the events unfolding around them in the broader unfolding of the their day, or of their lives, as a reminder of time’s passage and of their own mortality.

The worship services we have recreated include the sounds of the organ and the human voice. Festival worship services at cathedrals like St Paul’s in the early seventeenth century may also have included the sounds of other kinds of instruments, including stringed instruments and wind instruments of various kinds. Unfortunately, in our parallel universe, budgets precluded the hiring of instrumentalists other than the organist. So here is one of the organ voluntaries we included in our recordings.

THE ORGAN

THE VOICE

The other instrument involved in our worship services is of course the human voice, which appears in a variety of uses.

Spoken, solo, addressing the Congregation

Spoken, solo, in Prayer (with congregational response)

Spoken, solo, Blessing

Spoken, solo, Words of Comfort

Spoken, solo, reading from the Bible

Spoken, corporate, prayer

Chant, solo, chanting biblical passage

Chant, corporate, call and response

Sung, corporate, Creed

Sung, corporate, Canticle

Sung, corporate, Anthem

Sung, Anthem with organ

EXPLORING AMBIENT NOISE

Ambient noise — the constituting elements of the early modern London soundscape — was a major component of the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project’s acoustic modeling. We wanted to include the experience of listening to Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon against the background of some, but certainly not all, of the kinds of ambient noise that would have provided an acoustic background to the preacher’s delivery.

We wanted to do this because one of the major questions we sought to explore in that Project was the audibility of a preacher delivering a sermon in an open space of significant size without amplification for his voice. So we chose to include a selection of sounds for which Gipkin’s painting of a Paul’s Cross sermon provides documentation.

These include horses, birds, and dogs, which are programmed to be heard randomly during the course of the preacher’s delivery, without and effort to “script” their appearance. One can explore the result of our efforts on the Virtual Paul’s Cross website, here.

Ambient Interior Noise

For the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project, however, the question of ambient noise is both less and more complex. The Cathedral Project’s acoustic modeling recreates the sound of worship inside the Cathedral, and especially in the Choir of the Cathedral, where worship services were conducted.

The Bell

The bell, on the other hand, provides a different kind of ambient acoustic experience. Thanks to Tiffany Stern’s research (2011), we know that the clock at St Paul’s Cathedral sounded the time on the quarter hour as well as on the hour. This bell was certainly audible inside the Cathedral.

In our recordings of worship services inside the Cathedral, the bell ( a struck clock bell, not a swinging peal bell) is audible, its sound modeled to reflect the softer, yet still audible, sound of the bell as heard from within the Choir of the Cathedral as it rings out the hours and quarter hours during the portions of the day in which the worship services were being conducted.

On Easter Sunday, the clock bell sounds out 10:00 at the beginning of Morning Prayer, then every quarter-hour through the sequence of morning services. According to our experience, this sequences of services would have lasted — with a sermon during Holy Communion — for just over 4 hours.

One of the major questions we faced in this Project has been the question of whether the three services of the morning — Morning Prayer (or Matins), the Great Litany, and Holy Communion — were conducted sequentially, without breaks in between, or whether there were breaks of an unknown amount of time between them. We decided, finally, to stage them as one continuous service, separated only by short organ voluntaries to signal that one service was ending and another was beginning. This accords with William Harrison’s description as well as avoids working out whether or not services separated by a significant break would have required processions of clergy and musicians out at the end of one service and processions back in before the beginning of the next.

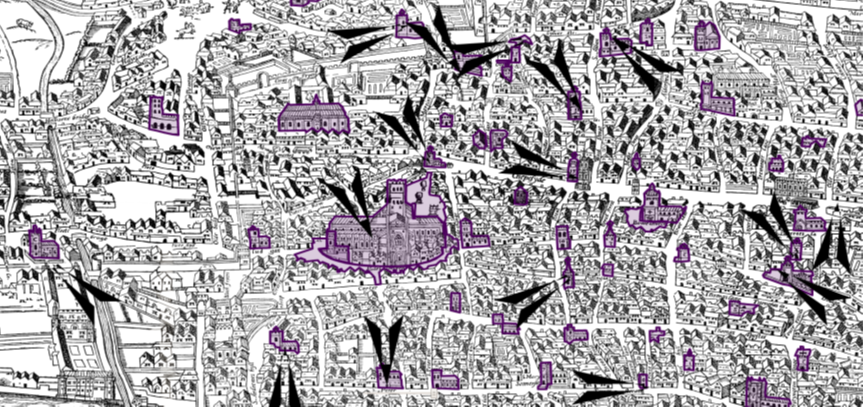

For Evening Prayer, the clock can be heard sounding 4:00 as the service begins. This works well for listening purposes inside the Cathedral. But we now have recognized that the Cathedral’s clock bell was not the only bell one could have heard if one were standing outside, in Paul’s Churchyard, let us say at 11:00 in the morning. The research of Paul Glennie, Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of Bristol, and a historian of church bells, has helped us identify a number of other churches near St Paul’s which also had clocks with bells.

We figured out that a bell rung within 500 meters of Paul’s Churchyard would have been noticeable audible (not just potentially audible) within the Churchyard. We figured out from Glennie’s research into the bells of London’s churches that there were 14 buildings with striking clocks within that radius, including St Paul’s, the Royal Exchange, and 12 churches. The churches were St Michael le Querne, St Benet’s, St Andrew by the Wardrobe, St Margaret Moses, St Michael Queenhithe, St Peter Westcheap, St Michael Wood Street, St Botolph Aldersgate, St Bride’s, St Olaf, St Anne and St Agnes, and St Alban Wood Street.

We then created 14 tolls of 11 bell-strokes. Based on Sterne’s research into the lack of synchronicity among the clock bells, we started our tolls a bit prior to 11:00 and staggered the entry of each toll, so that the entire time of all 14 tolls extends a good bit beyond the time a single toll would take. While doing so, we varied the sound of the bells so each discrete tolling of 11 AM would be (at least slightly) distinct in tone from the others. We also changed the volume of each toll to reflect the distance each one was from Paul’s Churchyard.

We then ran into a problem of representation, because folks who listened to our audio file of the bells tolling would inevitably turn their speaker volume up to hear the softer tolls, then be stunned when the closest tolls started at a much louder level. We tried several ways of modeling this and discovered that to make the file useful to folks we needed to compress the volume levels of the different tolls into a narrower range than we computed was most realistic. So we decided to compress the range of loudness variation from toll to toll into a narrower than acccurate range. As a result, the closer bells would have been louder than presented here, and the furtherer ones would have been softer.

So, click below to hear our simulation of the sound of clock bells at 11:00 am as heard by someone standing in the Cross Yard outside of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Paul’s Walk

The big exception to our generalization about the walls of the Cathedral screening out ambient noise is of course the sounds emanating from the Cathedral’s Nave, the famous Paul’s Walk, the largest enclosed space in London, notorious in this period for being so noisy that it disrupted worship in the cathedral’s Choir.

Thomas Dekker, in his The Dead Terme. Or, VVestminsters complaint for long vacations and short termes, has the character Paules Steeple describe the goings-on in Paul’s Walk:

What whispering is there In Terme times, how by some slight to cheat the poore country Clients of his full purse that is stucke vnder his girdle? What plots are layde to furnish young gallants with readie money which is shared afterwards at a Tauern) therby to disfurnish him of his patrimony? what buying vp of oaths, out of the hands of knightes of the Post, who for a few shillings doe daily sell their soules? What layinge of heads is there together and tilting of the brains, still and anon, as it growes towardes eleuen of the clocke, (euen amongst those that wear guilt Rapiers by their sides) where for that noone they may shift from Duke Humfrey, & bee furnished with a Dinner at some meaner mans Table? What damnable bargaines of vnmercifull Brokery, & of vnmeasurable Usury are there clapt vp? What swearing is there: yea, what swaggering, what facing and out-fasing?

What shuffling, what shouldering, what Iustling, what Ieering, what byting of Thumbs to beget quarels, what holding vppe of fingers to remember drunken mée∣tings, what brauing with Feathers, what bearding with Mustachoes, what casting open of cloakes to publish new clothes, what muffling in cloaks to hyde broken Elbows, so that when I heare such trampling vp and downe, such spetting, such talking, and such humming, (euery mans lippes making a noise, yet not a word to be vnderstoode,) I verily beléeue that I am the Tower of Babell newly to be builded vp, but presentlie despaire of euer béeing finished, because there is in me such a confusion of languages.

For at one time, in one and the same ranke, yea, foote by foote, and elbow by elbow, shall you sée walking, the Knight, the Gull, the Gallant, the vpstart, the Gentleman, the Clowne, the Captaine, the Appel-squire, the Lawyer, the Usurer, the Cittizen, the Bankerout, the Scholler, the Begger, the Doctor, the Ideot, the Ruffian, the Cheater, the Puritan, the Cut-throat, the Hye-men, the Low men, the True-man, and the Thiefe: of all trades & professions some, of all Countryes some; And thus dooth my middle Isle shew like the Mediterranean Sea, in which as well the Merchant hoysts vp sayles to purchace wealth honestly, as the Rouer to light vpon prize vnjustly. Thus am I like a common Mart where all Commodities (both the good and the bad) are to be bought and solde. Thus whilest deuotion kneeles at her prayers, doth prophanation walke vnder her nose in contempt of Religion. [1]Note: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A20054.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext)

We considered trying to model Dekker’s description of the sound generated by a crowd of folks behaving as Dekker describes. But we finally gave up. The important thing about Paul’s Walk, for our purposes, is the fact that the Nave of the Cathedral was often crowded, although not necessarily at every service time — some sources describe the crowds as assembling in the late morning, then taking a break for lunch, only to return in the early afternoon — and that the sound of the crowd sometimes was audible in the Choir during times of Divine Service.

To capture some sense of what this must have sounded like, we created the three tracks below. Each allows us to hear the clergy and singers seek to begin the opening of the service of Evening Prayer on the Tuesday after the First Sunday in Advent in 1625. Each also includes general crowd sounds, at different volume levels, all heard from Position B in the Choir. If the clergy and musicians who complained about the noise coming over the Choir Screen and distracting them from their work of Bible readings, prayers, and thanksgivings spoke truthfully, their experience at the beginning of Divine Service may have sounded something like this:

References

| ↑1 | Note: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A20054.0001.001/1:5?rgn=div1;view=fulltext |

|---|