Goals for the Visual Model

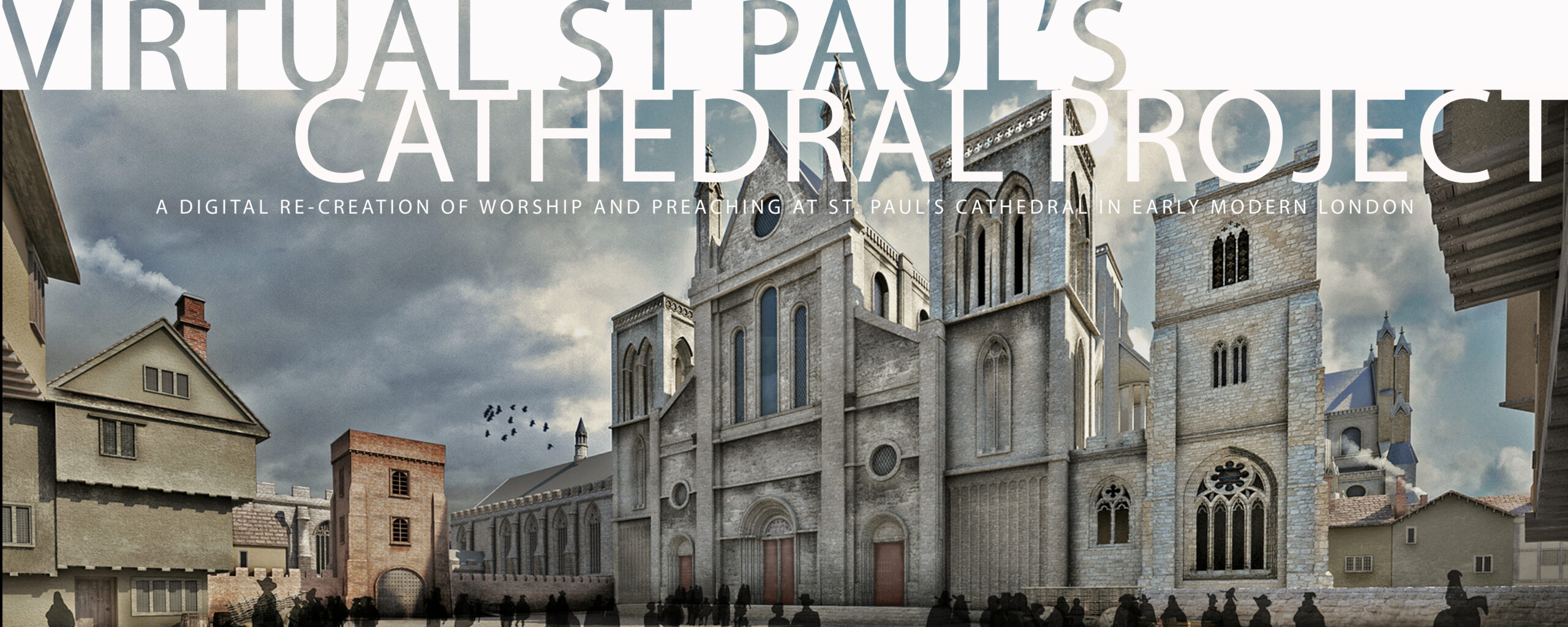

Our goals for creating the visual models of St Paul’s Cathedral and the buildings surrounding it in Paul’s Churchyard have been to achieve the highest possible degree of accuracy and authenticity in our work. Nonetheless, due to gaps in the evidence, we have had, from time to time, to infer various aspects of our models from the data we have or — when only minimal data is available — to use models representative of the genre or type of building we know or believe to have been in that spot.

One way of thinking about the visual model is to imagine it as an exercise in data visualization, not unlike a pie chart or a bar graph. In this case, however, the number and kinds of sources, their relative accuracy and authenticity, and their incorporation of nonrepresentational conventions of display exceed significantly the number of variables usually integrated in conventional data visualizations.

A good bit of information survives from pre-Great Fire London to help us achieve that goal. Unfortunately, the data we have is often partial, fragmentary, contradictory, or imcomplete. On a number of occasions, we have had to fill in missing portions of the data with what we hope to be informed guesses.

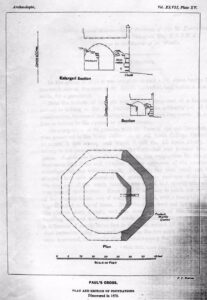

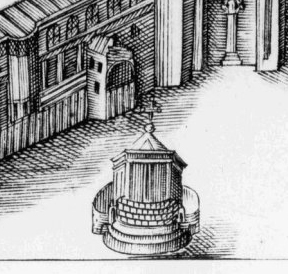

A good example of this is our model of the Paul’s Cross preaching station, visible on the website of the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project. Thanks to the work of Francis Penrose, Surveyor to the Fabric of St Paul’s in the late 19th century, we know with high accuracy the size of the base of the structure.

Penrose excavated the foundations of Paul’s Cross and published his findings. To read Penrose’s full account of his survey of the Paul’s Cross foundations, go here: Penrose Archaeologia (1883)

Penrose’s measurements only give us a design for the base of the structure and a sense of its overall scale. To move upward from the base, we turn to images of Paul’s Cross that survive from the early modern period. Although they differ in many details, they give us a pretty good general idea of what it looked like.

courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

What we don’t know, however, is the height of the building. The height we finally decided on is based on an assessment of the overall structure with regard for proportion, overall scale, and a sense of what height was needed for the structure to function comfortably as a setting for a two-hour-long event.

The models of buildings one sees on this website embody data that exhibit a range of levels and types of accuracy, of specificity or general categorization, of levels and types of accuracy. Images shown on this site reflect decisions that easily could have resulted in different images altogether.

Our models are, therefore, at best a mixture of hard data, inferences, and approximations of the objects and spaces they recreate. We use them best when we recognize that they are not mirror images of reality but tools for interpreting their subjects, as important for what separates them as they are for what links them to their subjects.

As this discussion suggests, the data we have available, while considerable, does not provide everything we need to know to produce a completely data-driven model. Although everything one sees in our model is based on a careful consideration of the historic record, there remain gaps to close, conflicting evidence to evaluate, choices to make, assumptions to ponder and question.

The models of buildings one sees on this website embody data that exhibit a range of levels and types of accuracy, of specificity or general categorization, of levels and types of accuracy. Images shown on this site reflect decisions that easily could have resulted in different images altogether.

We can sort the kinds of data available to us into the following categories:

1. Data-based accuracy — information that is accurate in the sense that it is based on actual measurements, like measurements of the cathedral’s foundations

2. Historic accuracy — information that comes to us from the historic visual record, which is only as good as the image is accurate. After all, Hollar’s drawings do not always agree with his engravings. Which should we follow, if we have both?

3. Representational accuracy — when, as is the case for many of the buildings in the Churchyard, we have the measurements of the foundations of the building, and maybe a detail or two about the number of stories or number of garrets, but no further details. But we know from other evidence what kind of building it was, and we know what features buildings of that kind had, so we can create a representation of that kind of building based on other buildings of that kind for which we have images or can look at surviving examples.

4. Informed guesswork — what we do when we know some things, but not others, so we have to make a guess about the missing details.

Modeling the Cathedral — the Exterior Model

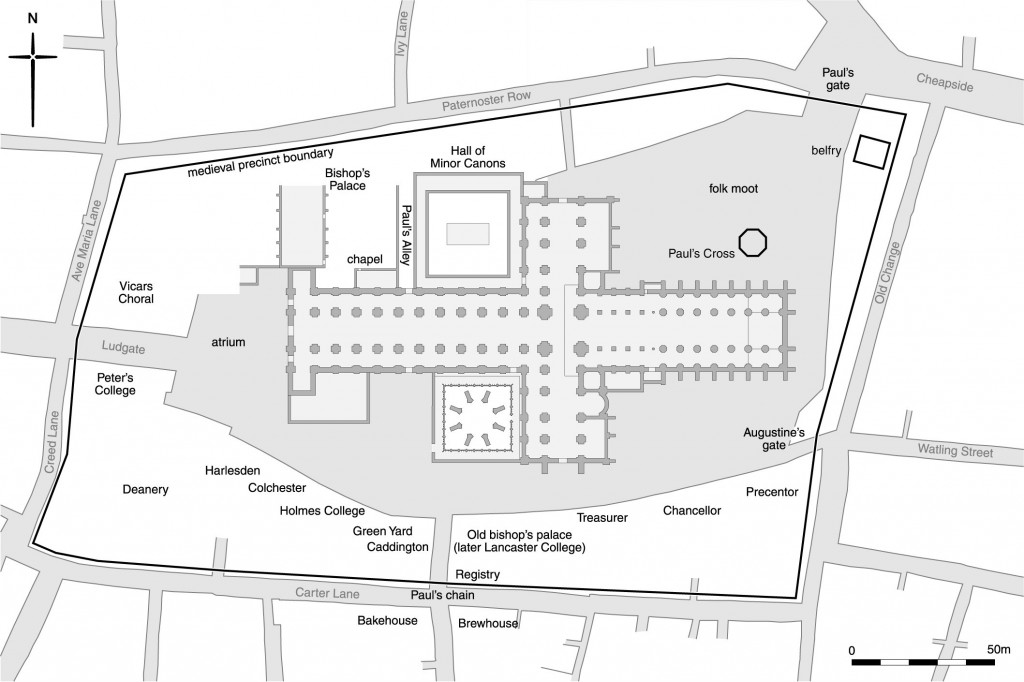

We started our modeling literally from the ground up. The Cathedral’s original foundations partly survive in the ground atop Ludgate Hill. They have been surveyed by archaeologists who have determined with a very high degree of accuracy the basic shapes and dimensions of the structure’s foundations.

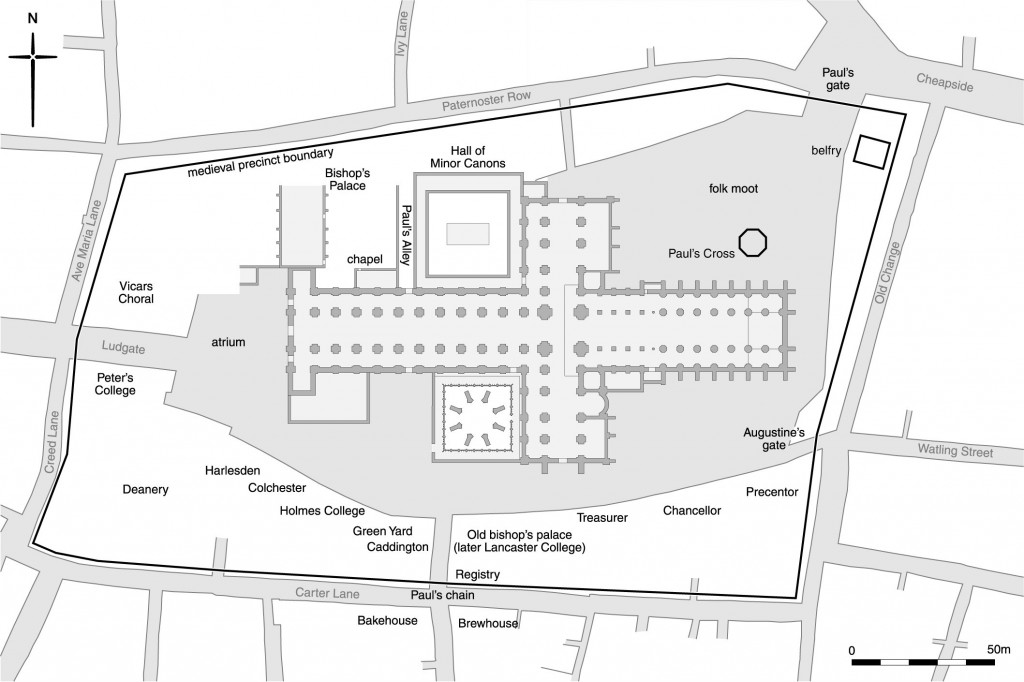

John Schofield, St Paul’s archaeologist, has gathered all this data into his monumental study St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren (English Heritage, 2011), a volume absolutely essential to our work. From Schofield’s work, we have derived the basic floorplan for the Cathedral, the basic measurements of the buildings and the space around them, and the basic geometry of the Churchyard itself.[1]For a discussion of the design and construction of St Paul’s in the context of other English and continental cathedrals, see Christopher Wilson, The Gothic Cathedral (London, 1990).

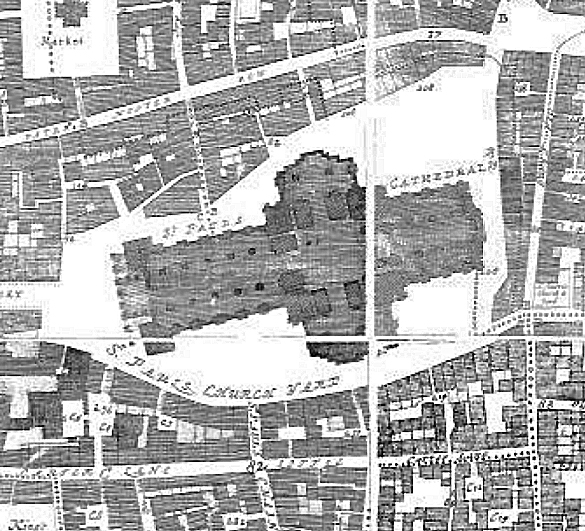

For the layout and locations of buildings around the Cathedral, we have relied on two basic sources of information. The first is a map of the Churchyard from the post-Fire Map of London by John Ogilby and William Morgan, which shows the lot lines of pre-Fire buildings. The second is Peter Blayney’s The Bookshops in Paul’s Cross Churchyard, a study, based on post-Fire lot surveys, of buildings occupied by booksellers in the northeast quadrant of the Churchyard. [2]The Bookshops in Paul’s Cross Churchyard (London: Bibliographical Society, 1990.

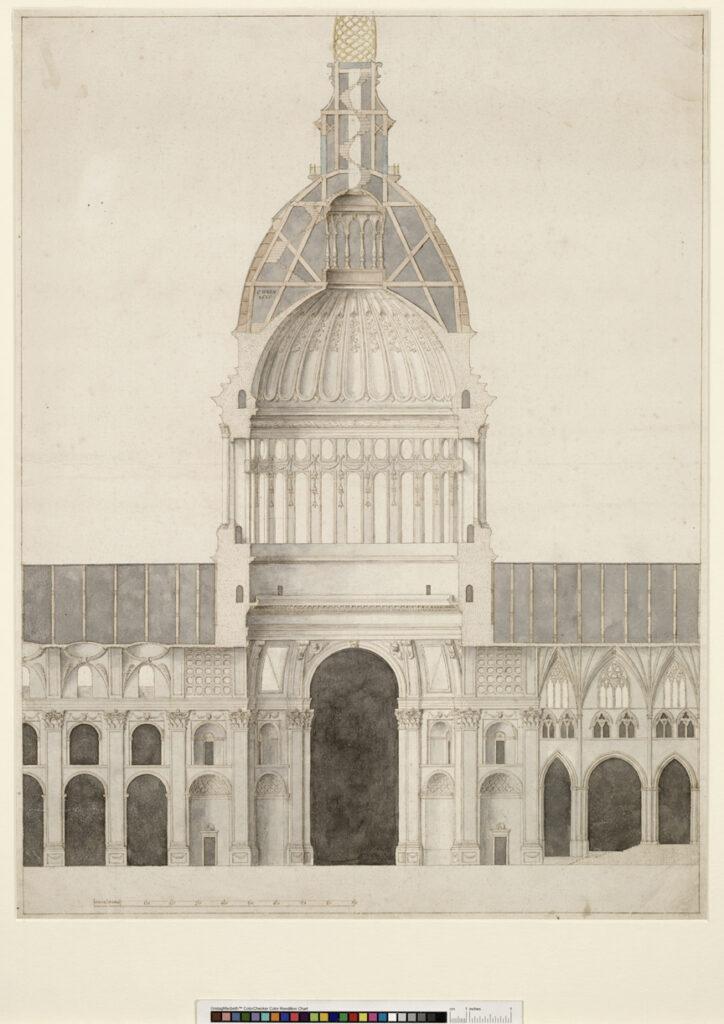

We have drawn on an unusual source for our measurements of the height of the Cathedral, Christopher Wren himself, who produced drawings showing sections of the Cathedral’s interior and a partial plan of the Cathedral in 1665 as part of his plan for remodeling the building. Wren thus provided us with the measurements for the shape and height of the arches, the windows, and the ceiling of the building’s various sections.

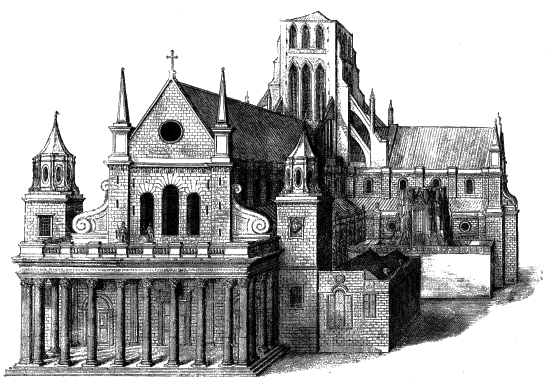

Wren was in the right time and the right place to be hired to plan the rebuilding of the Cathedral after it was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666. One can see in this drawing that the style and some of the features of Wren’s St Paul’s were already in his mind, regardless of what one thinks about the integrity of plopping a classical domed structure on top of a medieval building.

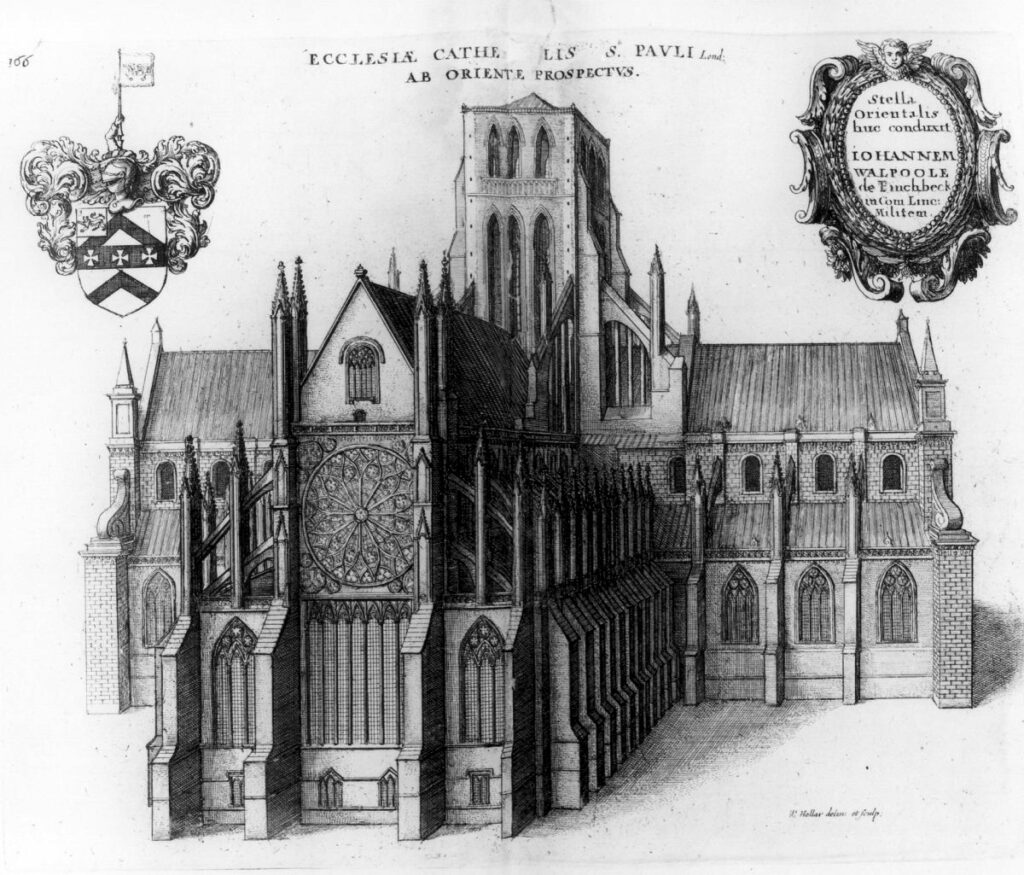

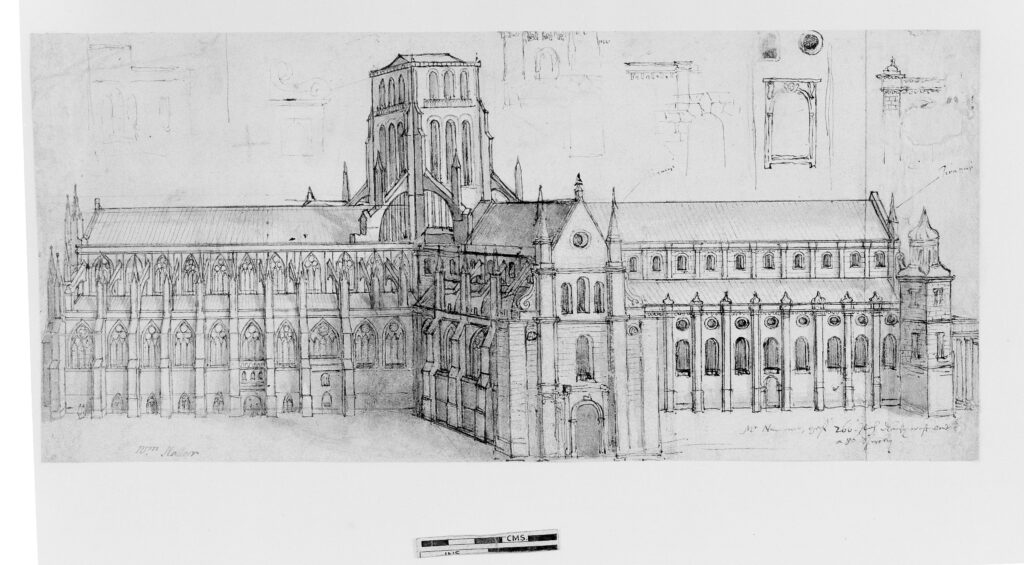

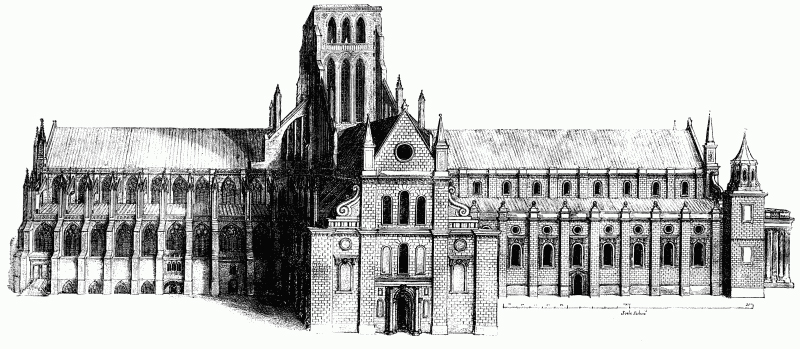

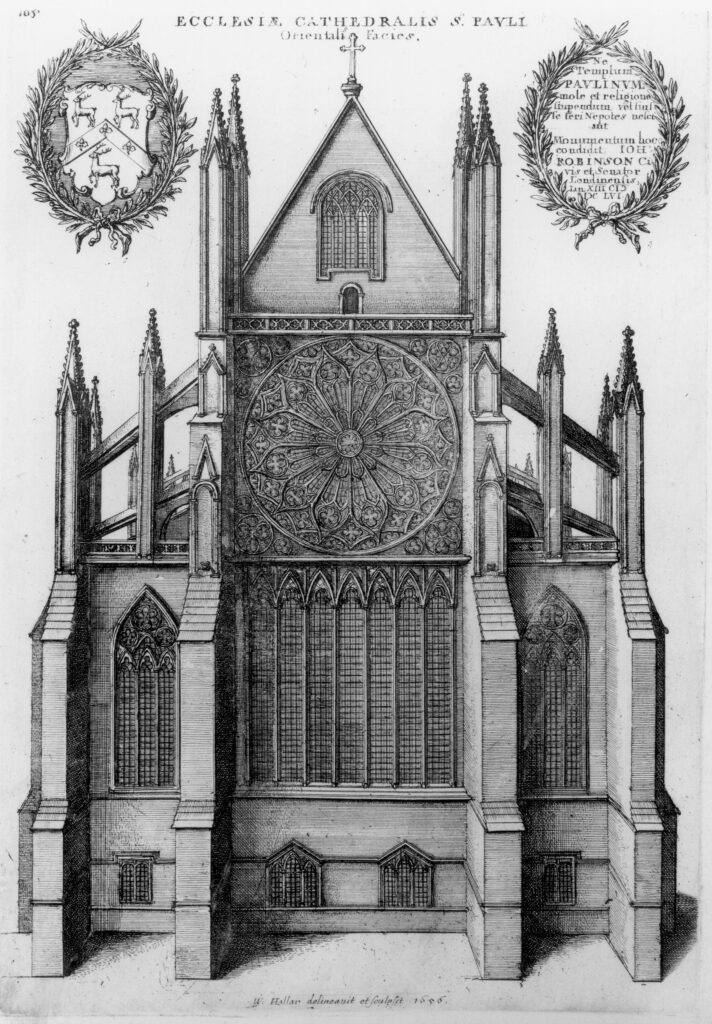

After the details we learned from the work of archaeologists and from Wren’s drawing, the most important source of information about the look of pre-Fire St Paul’s has come from the remarkable set of engravings that the Bohemian artist Wenceslaus Hollar prepared in the 1650’s for the English author William Dugdale, as illustrations for Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658).

Hollar’s set of engravings covers both the interior and the exterior of the Cathedral. They have been invaluable to us in imagining details of the Cathedral’s design and appearance.

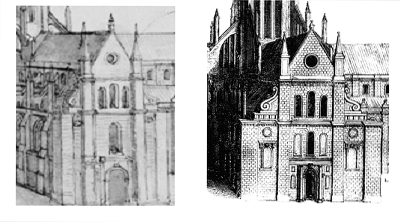

A small number of Hollar’s original drawings survive as well, most notably this image of the Cathedral’s east front and the following image of the Cathedral’s south side.

This image of the Cathedral’s south side, however, when compared to the engraving Hollar prepared for Dugdale’s book, points to the challenge sometimes presented by the surviving visual record.

While Hollar’s drawing is superficially identical to his engraving, we found that upon closer examination, differences between the two begin to appear.

For example, did the Cathedral — in the design of the facade of the South Transept — have one (the drawing, on the left, below) or 3 (the engraving, on the right, below) rounded-top structures over the main door? Were the panels to the left and right of the main door narrow without decoration (the drawing) or wider and decorated with carved panels (the engraving)? Were these panels narrow (the drawing) or wide (the engraving)?

This specific instance of variation between the drawing and the engraving — both by the same artist — was not important to us, because this part of the Cathedral shows, in Hollar’s drawing and engraving, a facade that is part of Inigo Jones’ neoclassical remodeling of the Cathedral from the late 1630’s, thus not a feature of the Cathedral as Donne would have known it. But the point here is that the visual record, the collection of images of St Paul’s Cathedral that come down to us from the early modern period, is not to be taken on face value, without careful consideration.

John Gipkyn’s famous painting of about 1616 showing Paul’s Churchyard during the delivery of a sermon at the Paul’s Cross Preaching Station, for example, shows a radically truncated Nave to the painting’s right, as well as missing bays in its depiction of the Choir, not to mention its giving the Choir Norman windows instead of the Gothic pointed arches that Hollar shows in his images of the Choir.

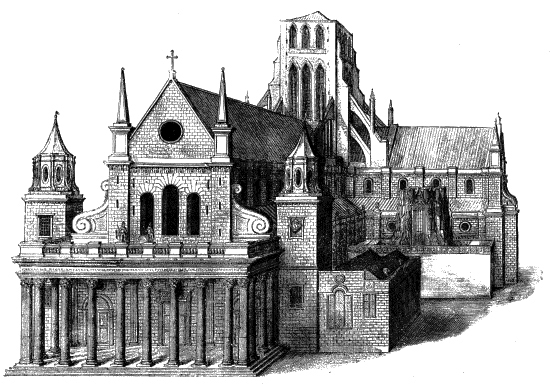

The Hollar images that show the exterior of the Nave and West Front also present the challenge of showing us not the facade of the Norman nave Donne would have known but the appearance of the building after Inigo Jones remodeled it in the mid-1630’s in a vaguely neo-classical style.

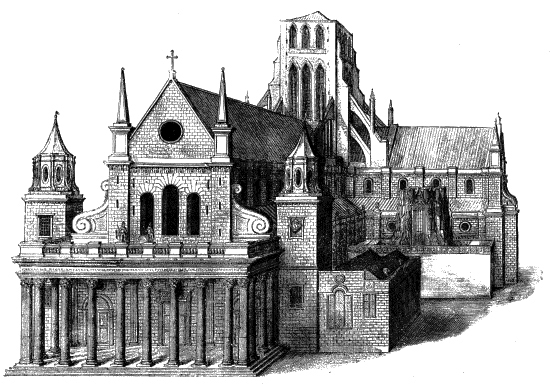

This is especially noticeable in his design for the West Front, but it is also the case with the North and South facades of the Nave. Hollar’s image, below, shows the Cathedral’s Chapter House in the center of the image, but shows Jones’ remodeled Nave facade to the left of the Chapter House and what we presume to be the Cathedral’s original Norman facade to the right of the Chapter House.

We, of course, based our configuration of the north and south facades of the Nave on Hollar’s treatment of this part of the South Facade.

Our goal in all areas of the Cathedral in which Jones covered the historic facade has been to see what design lay beneath Jones’ work. But, as we will discuss when we get to the Cathedral’s West Front, on some occasions Jones’ work is an important source of clues to what we believe to be the original design.

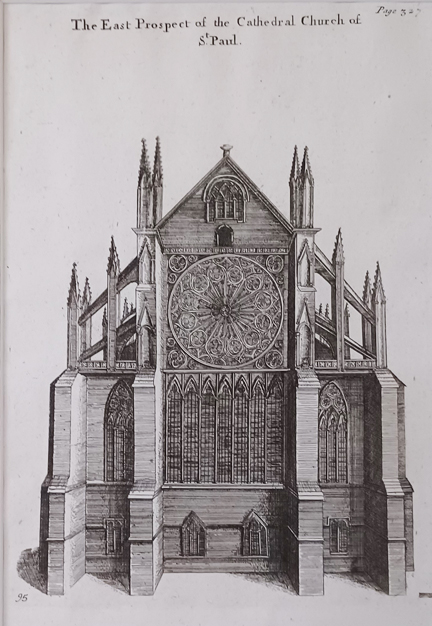

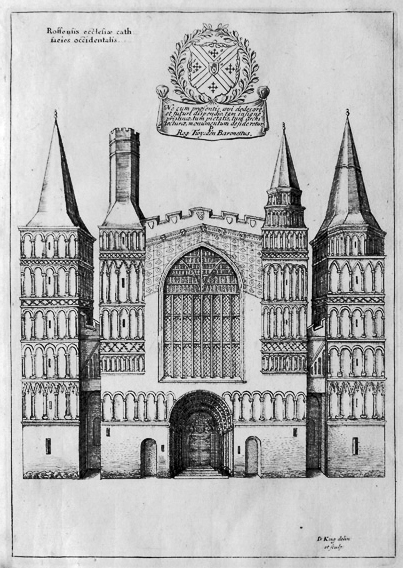

Other engravers made images of St Paul’s Cathedral, including Daniel King, who made this engraving of the East Front for his book Cathedrals and Conventuall Churches of England and Wales, published in 1656. King’s version essentially duplicates Hollar’s version of this view, but with small differences in the details. Hence we have the same challenge here as we do with Hollar’s own drawings and engravings of the same view of St Paul’s — to sort out and evaluate the differences and decide how to treat them

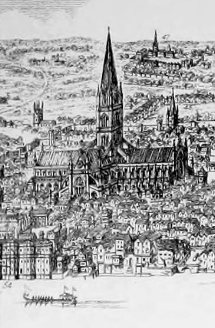

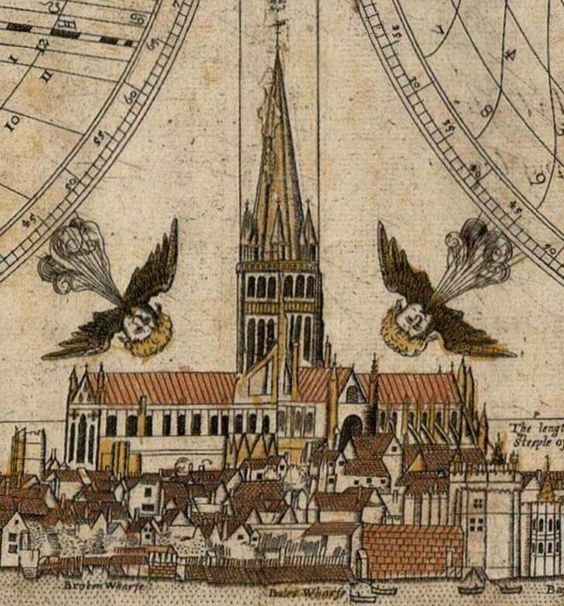

Other early modern images of St Paul’s Cathedral and its environs help us fill in details. The image below, from the Panoramic View of London by Antony Van del Wyngaerde, circa 1545, shows the cathedral with its spire intact.

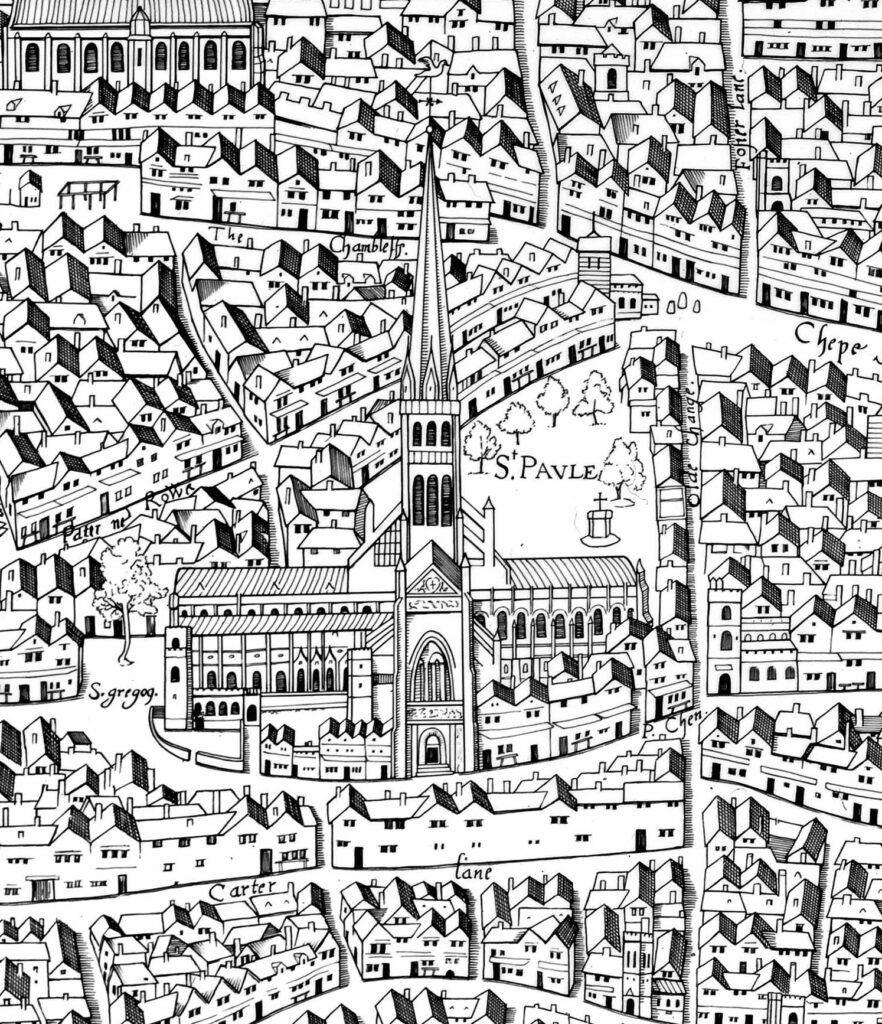

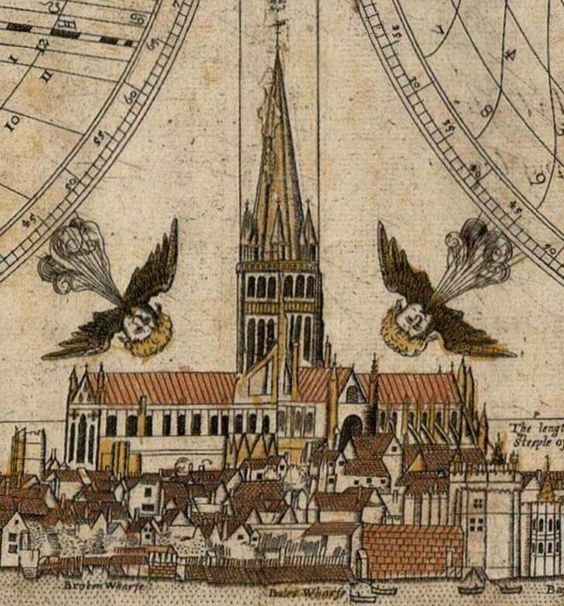

The image below, for example, from the “Copperplate Map,” shows the cathedral around the middle of the 16th century, with its spire intact.

The image below also shows the spire before it was struck by lightning in 1561. This image is important because it is one of the few to give us a glimpse of the West Front before Inigo Jones got his hands on it in the 1630’s.

The image below, from the Agas Map of 1563 shows the Cathedral after the ligntning strike and fire that destroyed the spire.

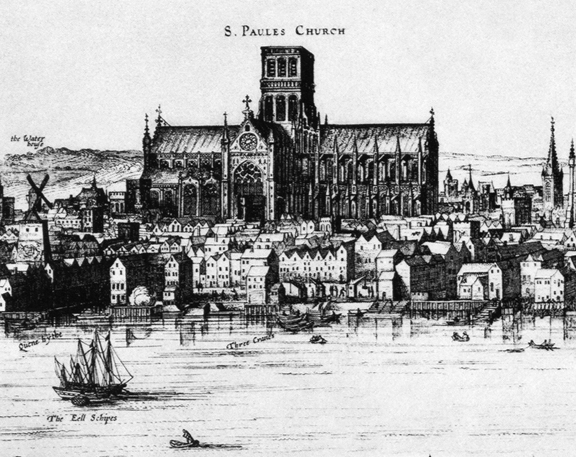

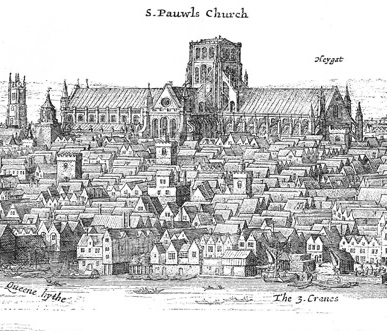

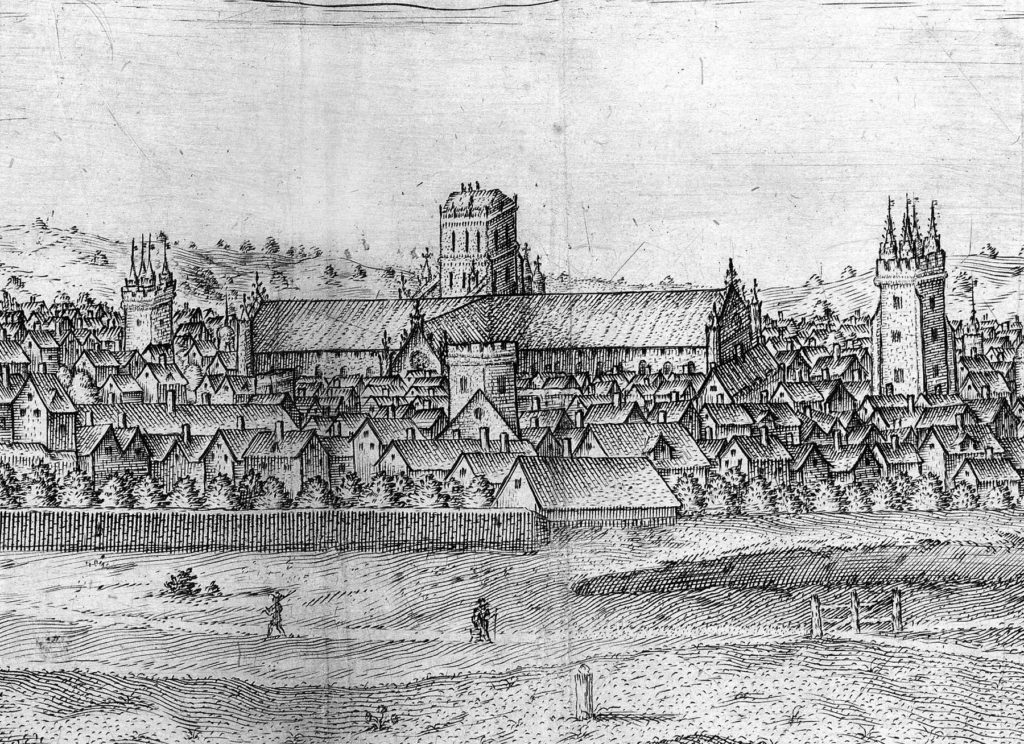

The image below of St Paul’s is from a panoramic view of London by John Norden, published around 1600. Below it are images of St Paul’s from other panoramic views of London.together they remind us that medieval St Paul’s dominated the skyline of London in the early modern period even as Wren’s cathedral does today.

The image below is from Claes Visscher’s Panorama of London, published in Amserdam in 1616.

The image below, from 1625, shows St Paul’s as part of the background for a graphic depiction of London in the grip of the Plague. What is suggested here is that St Paul’s was so much a part of the identity of London as well as a fixture of its skyline that depicting it was essential to any imagining of the city, even the city in the grip of danger.

The image below shows a gold medallion cast by Nicholas Briot cast in 1633 to celebrate the return to London of Charles I, perhaps in July after that year, after his trip to Scotland. The truncated tower of St Paul’s rises up over the City of London in the image on the reverse side, surrounded by the Latin text SOL ORBEM REIENS SIC REX ILLUMINAT URBEM, which translates as follows: “As the sun illuminates the world so does the King’s return gladden the city.”

St Paul’s Cathedral, 1633. Medallion cast to celebrate Charles I’s return to London after his coronation in Edinburgh in 1633. Used by permission of the Museum of London

This medallion was also cast in silver, now in the collection of the British Museum.

St Paul’s Cathedral, 1633. From the collection of the British Museum ( MG 1442). Image courtesy of the Museum.

The image below is from a panoramic view of London by Wenseslaus Hollar, dating from 1647.

Finally, two views of St Paul’s from the north. The first is by by an anonymous artist, from about 1597.

The image below is a 17th century pen and ink drawing of St Paul’s Cathedral, here seen from the north. This image, formerly attributed to Rembrandt, is now in the collection of the Berlin State Museum.

St Paul’s Cathedral inscribed in Stone

The above image is to be found in St Mary’s Church, Ashwell, here:

St Mary’s Church Ashwell, Hertfordshire. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Data from Other Sources

We have also sought to incorporate information not usually included in visual models of historic sites. This includes, especially, information about the relative ages of the buildings and the times of day and the kinds of weather one would expect to find on the specific occasions we are recreating.

For illustration, the image above, from the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, shows our model of the cathedral’s Cross Yard, with the Paul’s Cross preaching station in the center, the Sermon House against the cathedral to the right, and the houses surrounding the Cross Yard to the left. The image below shows the same view after the addition of details that reflect the relative ages of these structures and the look of a chilly, overcast day appropriate for outdoors on a chilly day in London in early November.

The look of the houses in this image brings us to another topic, our understanding of how buildings of this type would have looked in the early 1600’s.

We are familiar with this way of imagining the external appearance of early modern houses, with their supporting timbers exposed, because we are used to it from our experience with surviving structures of this type in England. For instance, the image below, which shows the facade of the Black Swan Public house in Yorkshire.

We followed, for the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project, the current practice of imagining early modern residential and commercial structures as having exposed beams painted black or brown, in contrast to the plaster facades, often painted white or in pastel colors, that fill in the space between the timbers.

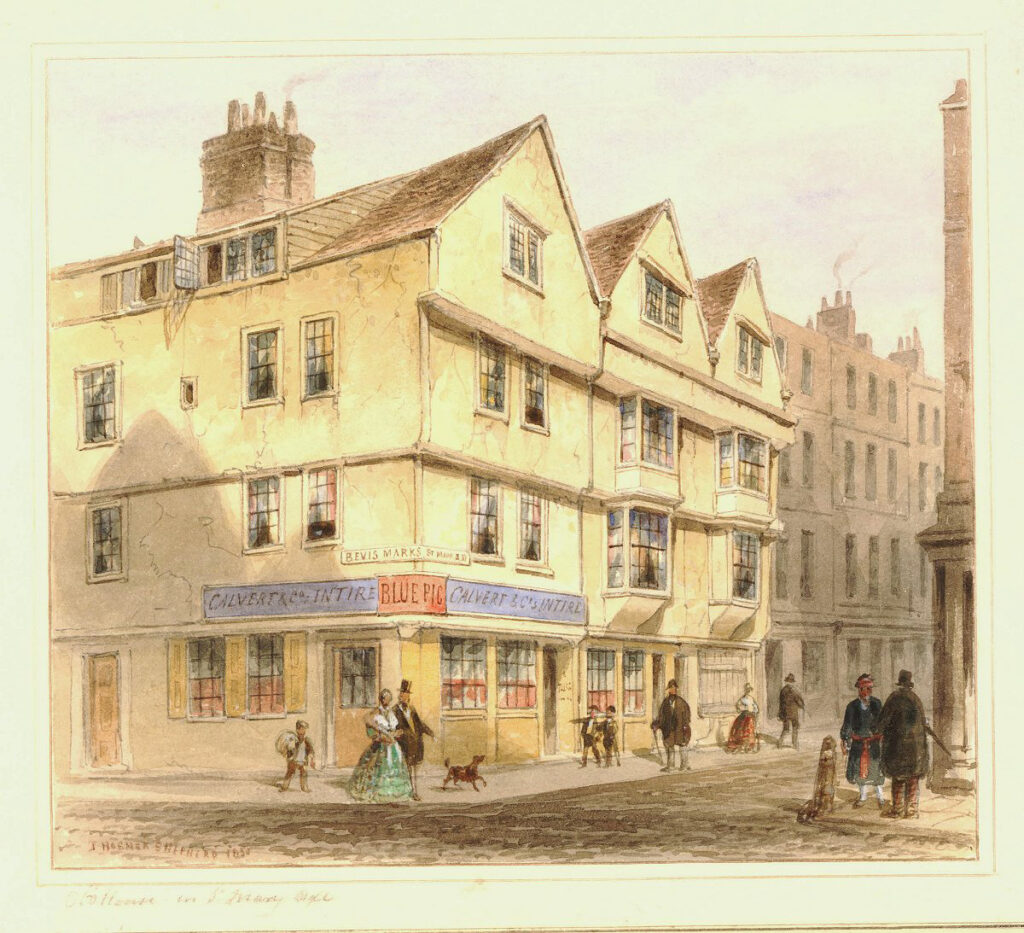

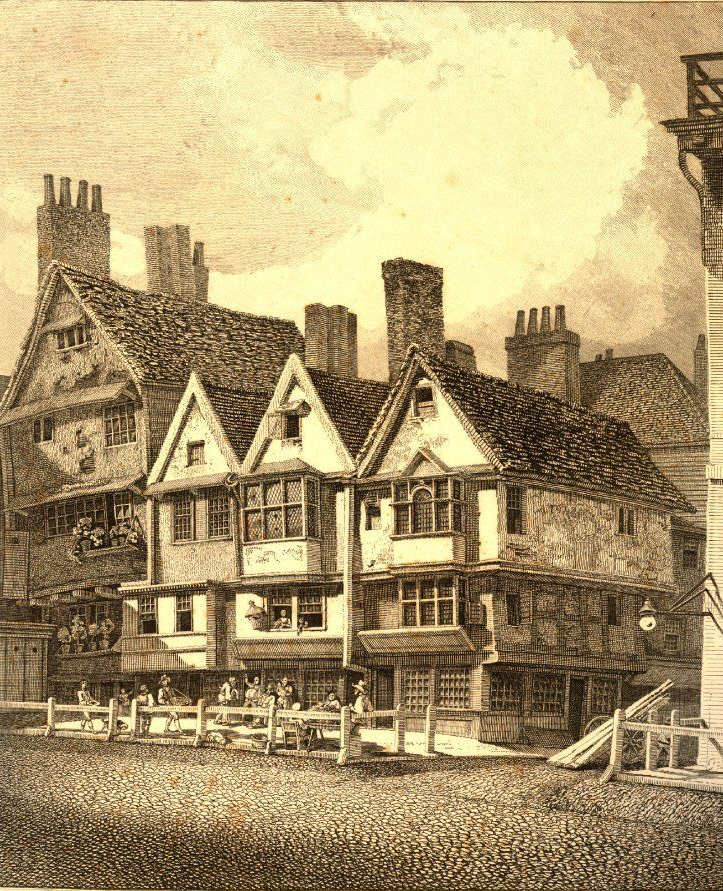

Houses in the Virtual Cathedral Project do not, however, look this way. After reviewing visual images of similar structures from the early modern period, for example the ones shown below, we found that the overwhelming majority of these images show buildings of this type as having plaster over the entire exterior of these buildings.

As a result, we have come to the conculsion that in the early modern period these buildings were plastered all over, not just between the structural timbers.

For discussion of this issue, see specifically Waldemar Komorowski, “Layering of Facades: A few comments on the colour of Krakow’s facades in earleir and contemporary times,” as well as the much broader discussion in John Schofield’s Medieval London Houses (Yale, 1995).

What this means, of course, is that the exposed-framing style of construction is a modern reinterpretation of early modern construction style, a reconstruction that ought to have a post-early modern origin-point and a history all its own. We look forward to reading such an account.

Representational Modeling I: The Case of the Bishop’s Chapel

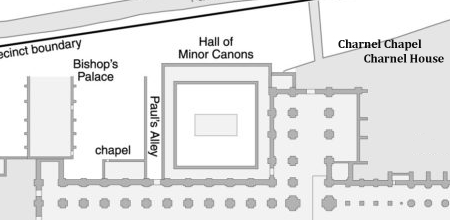

We also know that the Bishop of London had a Chapel that sat against the north side of the Cathedral, near the west front, adjacent to the Bishop’s Palace. We also know that, by the early 16th century, there was a large Cloister situated against the north side of the Nave, between the Bishop’s Palace and the North Transept, and south of the Hall of Minor Canons.

We also know that in the latter part of the 16th century this Cloister was demolished. We also know that after this Cloister was demolished, structures were built against the north side of the Nave. These structures served as workshops for tradesmen and craftsmen.

We know the size of the Bishop’s Chapel and the approximate era of its construction, but have no images of its appearance. We do not know the size or precise location of the workshops.

So the image above is representative much of our work, combining precise data (the location and size of the foundation of the Bishop’s Chapel), representational data (the appearance of a chapel of this size and era of construction), and guesswork (the location, size, and appearance of the workshops).

Representational Modeling II: St Paul’s Cathedral, the West Front

The most challenging part of modeling St Paul’s Cathedral in the early 17th century has been reconstructing the Cathedral’s West Front. This is because we were unable to find a complete visual depiction of the West Front as it looked before Inigo Jones’ remodeling work in the late 1630’s.

As a result, our visualization of the West Front constitutes the most speculative aspect of our visual model. Nonetheless, it is still based on a caareful review of the information available to us.

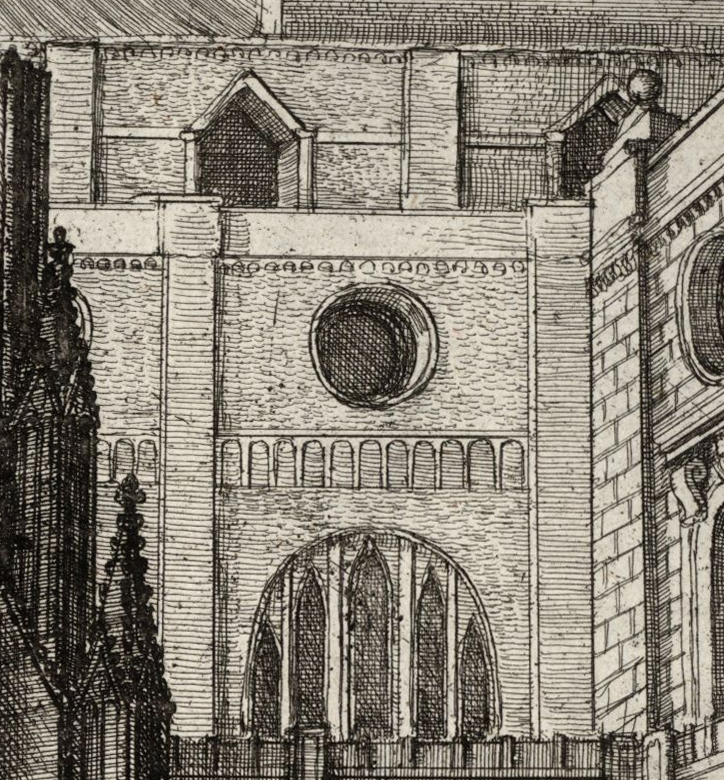

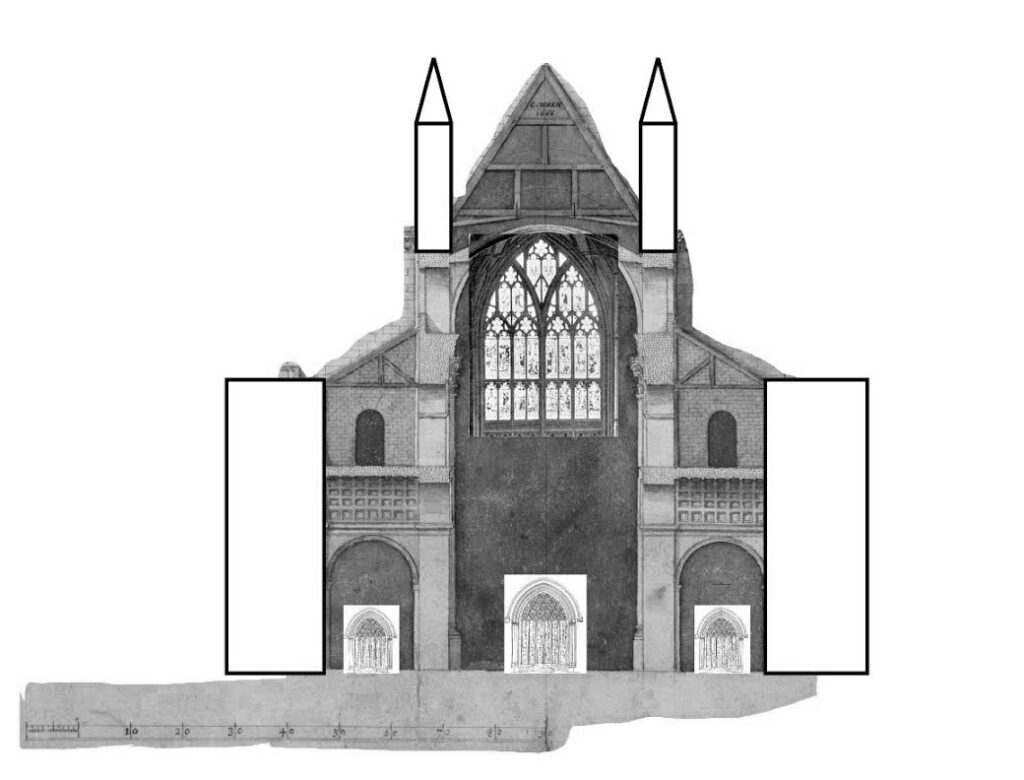

We do have partial views of the West Front which provide us with some clues as to the West Front’s appearance.

The image above shows the distinctive array of three tall windows in the facade, with the center of the three taller than the ones to its left and right.

This image shows the circular opening in the triforium and (perhaps) the top of the center of the three windows shown in the Prospect image.

Finally, this image at least suggests the circular window in the pediment and the long central window in the facade, below the pediment.

These images all show the West Front to contain a central rectangular form topped by the pediment and flanked by towers on each side. These images all display a configuration of multiple vertical windows in the upper section of the West Front, topped with a triangular pediment.

Two of the three images show a round widow located in the triforium.

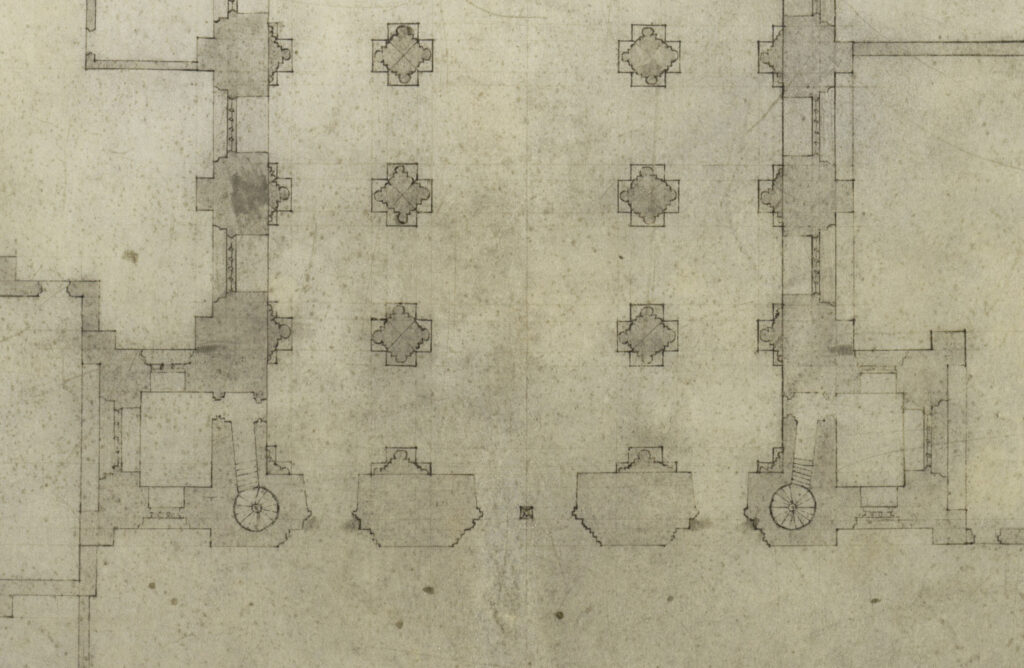

We also had visual evidence of the configuration of the West Front from this drawing of the Cathedral’s floor plan, showing the size of doorways, plllars, and other architectural features.

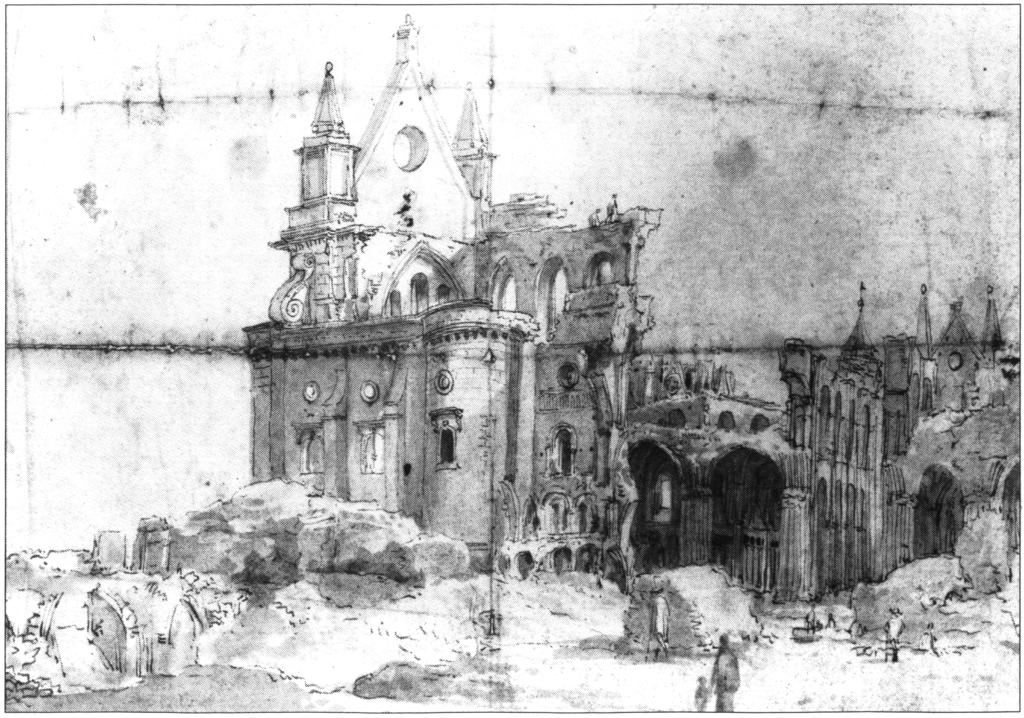

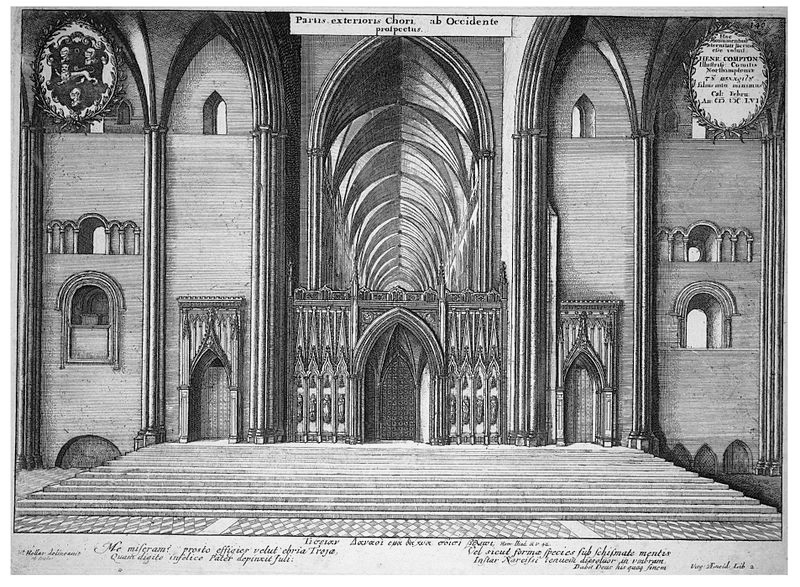

We then turned to assessment of the very problematic evidence provided by the visual record of the later seventeenth century.

Wenseslaus Hollar created a very detailed image of the West Front for Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s Cathedral, but it shows the West Front as recreated by Inigo Jones in the 1630’s, not the facade of the Norman cathedral.

Jones himself left us a preliminary draft of his plans for the West Front.

In spite of the imposition of Jones’s design, these images of the West Front show the persistence of the basic configuration of a pediment with a round window in it, over a rectangular facade, flanked on each side by a tower.

They also show a row of three windows, in which the center window is taller than the ones that flank it to the left and right. Both images of Jones’ work also show a large central doorway flanked on each side by smaller doorways.

We concluded that these elements would need to be included in our revisioning of the West Front.

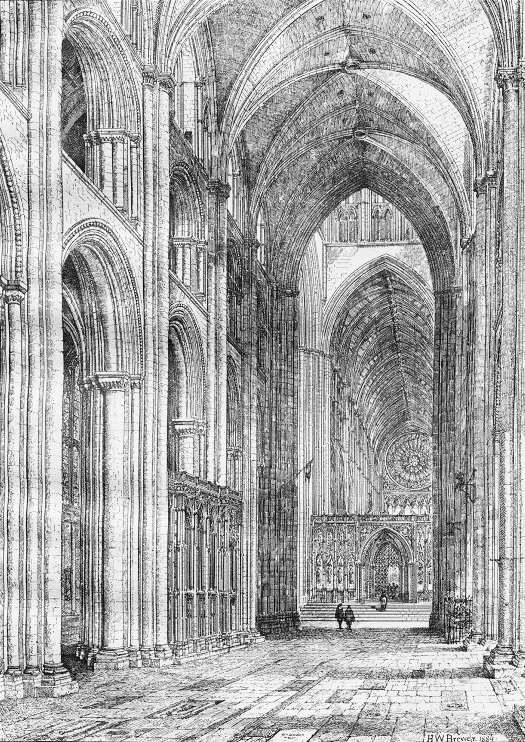

We then turned to Richard Halsey’s comment on the design of the interior of St Paul’s nave (in his essay in St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren on “Placing St Paul’s in the development of English greater churches” (pp. 233 – 236), that the nave “appears to be a design of the early 12th century that ultimately owes its three-storey elevation to Saint-Etienne, Caen.”

Fortunately for our purposes, this building survives so one can compare its interior design with Hollar’s image of St Paul’s Nave.

With Halsey’s insight about the interior of medieval St Paul’s as our guide, we discovered that the exterior of Saint-Etienne, Caen, looks like this:

Using this design as our guide, and incorporating the design elements for which we have strong evidence were part of St Paul’s West Front, we came up with this design for our model.

The result is a design that is more austere than other English cathedrals of this period. It does, however, incorporate the essential features documented by the 16th century visual images, together with the general style of St Etienne, in Caen.

Our sense of the austerity of this design is influenced by our knowledge of Norman cathedrals in England which have more ornate or complex designs. Part of that ornateness comes from the fact that many of them have been remodeled since their initial completion.

Images courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps the best example of a surviving Norman cathedral with which to compare our design for St Paul’s West Front is the cathedral at Rochester.

At Rochester, plans for a remodeling of the nave were shelved, preserving the original, austere Norman West Front. While slightly more ornate than our design for St Paul’s, this example reassures us that if we were actually able to visit London in 1600, we would recognize the West Front of St Paul’s.

All three of these cathedrals do show a single large window dominating the design of the West Front, while our model shows that space on the façade occupied by three slender windows. We considered patterning our design for St Paul’s West Front after these examples.

Such a move was supported by an image of the façade of the South Transept post-Fire, in which it is clear that Jones, in remodeling this part of the Cathedral in the 1630’s, filled in a large window space, topped by a pointed gothic arch, to install his three slender windows.

. Because of this image, we decided to model the façade of the South Transept with just such a window.

But, given the lack of any contemporary evidence that the West Front had such a window, and the evidence that it DID have the three slender window design, provided by the image from 1575 shown below, we decided to follow that evidence and to imagine that this design for the West Front influenced Jones to follow it when “neo-classicizing” the facades on the North and South Transepts.

Our Visual Models, therefore, are never more, or less, than the informed but still imaginative integration of surviving data. While other approaches to visualization might more accurately reflect the kinds, varieties, and absences of such data, the style we have adopted in this Project reflects our belief that — with all one’s sense of the limits on accuracy and the extent of approximation — the experience of seeing a model of the entire structure, however provisional or approximate in places that model might be.

The History of Reimagining the Exterior

As we developed the Visual Model, we discovered that much of what we thought we knew visually about the early modern Cathedral and its environs could be wrong. Our chief example this was of course the tradition of depicting domestic and commercial structures from this period with their framing timbers exposed and painted black to contrast with the whitewashed plaster walls filling in the spaces between the timbers. We came to recognize this mode of depiction as essentially a modern recreation of the past, one that could probably be dated to somewhere in the 19th century.

In the process of constructing the Visual Model, therefore, we wanted to make sure we used only visual data that had survived from before the Great Fire, because only those images had any chance of depicting what was there. We deliberately avoided looking at any post-Great Fire attempts at reconstructing what St Paul’s Cathedral looked like.

Having completed our Visual Model, however, we began to look at those who had gone before us in interpreting the pre-Fire evidence to see how our interpretations of the surviving preFire visual record compared with theirs.

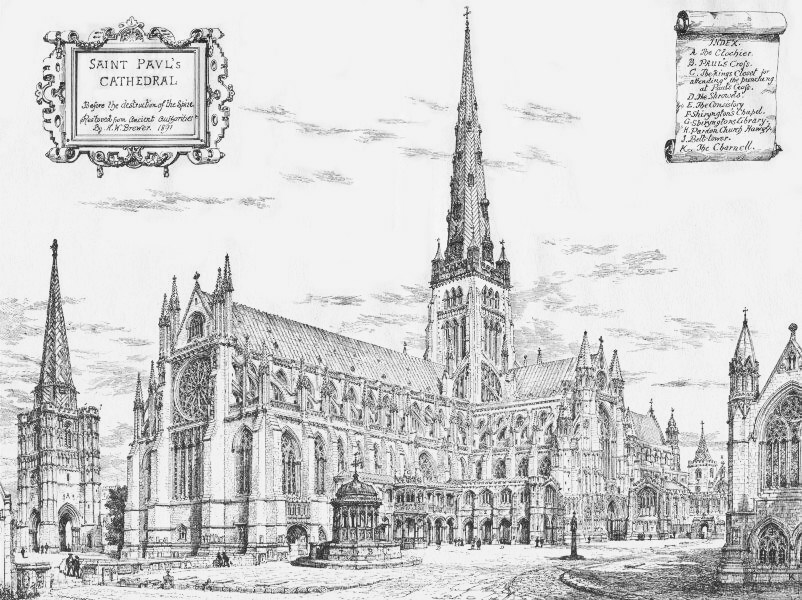

Here, for example, is an engraving by Henry W. Brewer, from the late 19th century, showing the Cathedral from the northeast sometime before the lightning strike of 1561 set fire to the Tower.

Another example is the model builder John Thorp’s model of the Cathedral, constructed in the early 20th century and now on display in the Museum of London.

We were particularly pleased to see how similar his reconstruction of the West Front is to ours.

Modeling the Cathedral — The Interior Model

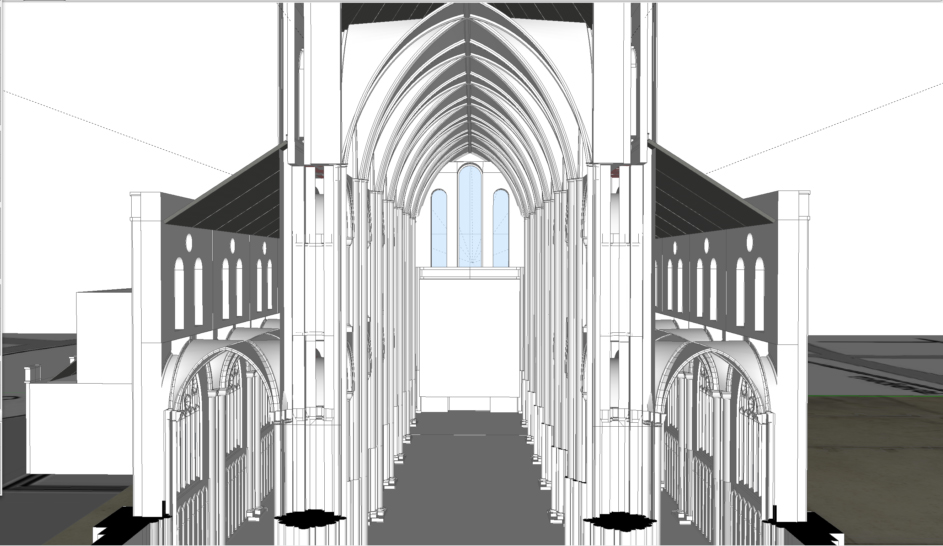

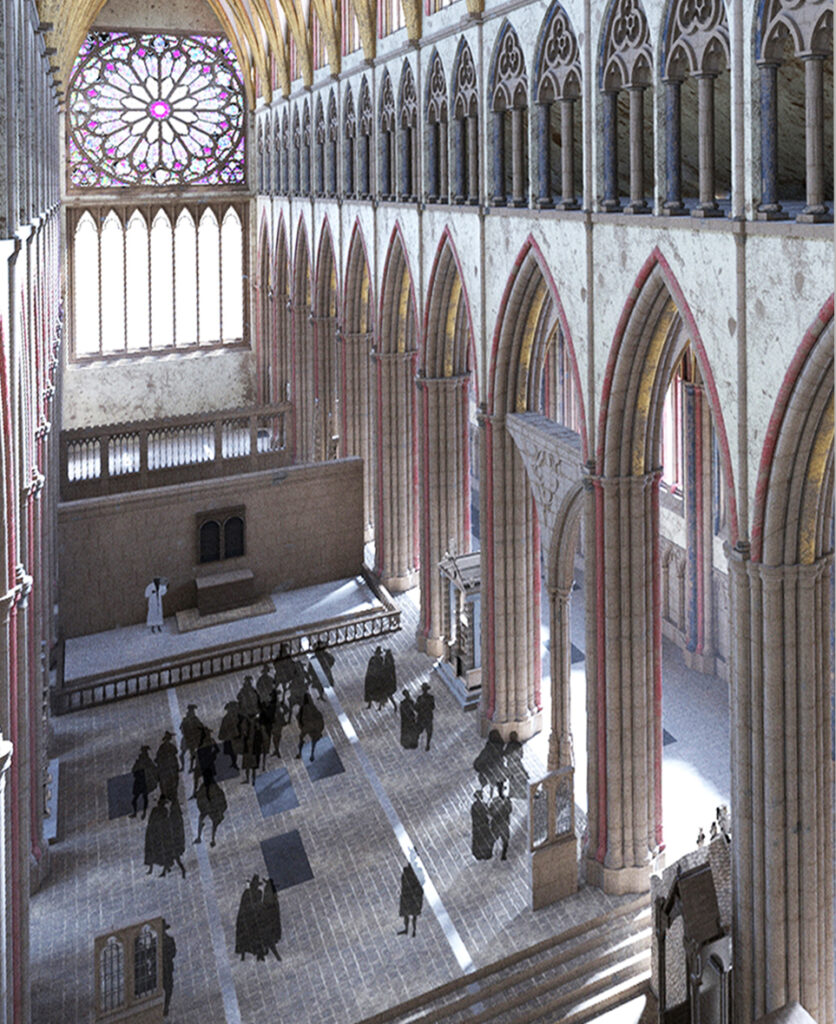

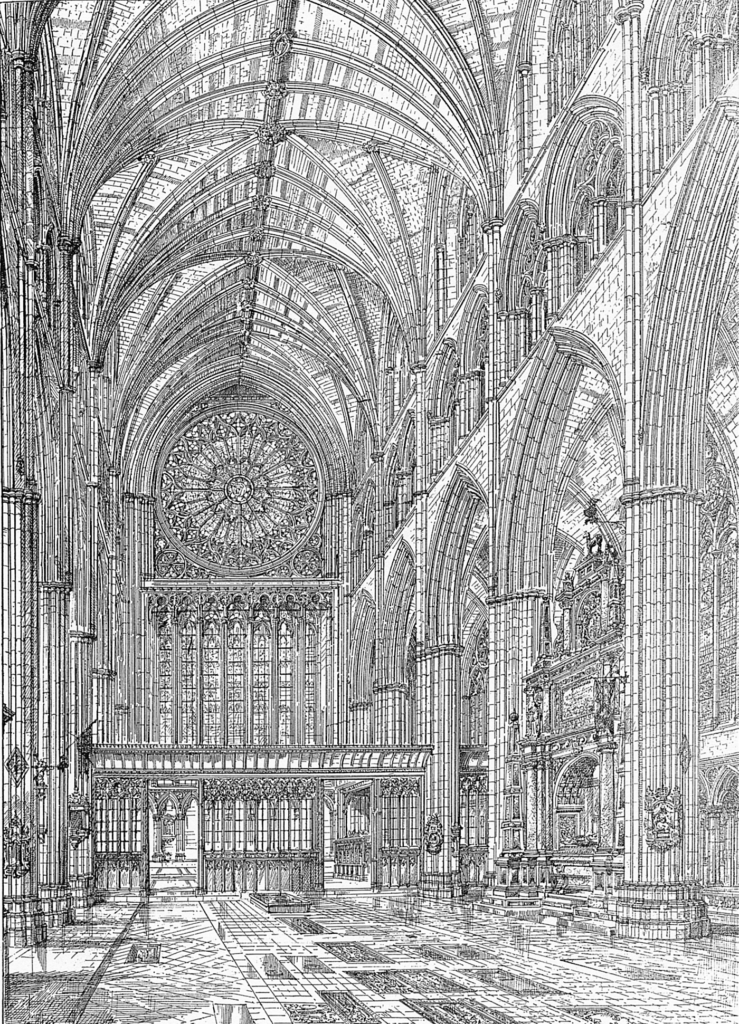

Modeling the Cathedral’s interior begins, of course, with the archaeological evidence for the shape, proportions, and dimensions of the Cathedral’s interior, evidence summarized by diagrams like the one above from John Schofield’s St Paul’s Cathedral Before Wren. From this kind of data, we understand the basic configuration of the spaces inside the building and their division into the spaces defined by the building’s components — the Nave to the west, the Crossing and North and South Transepts, and the Choir to the east. We also note the major points of access to the building — the three massive doors in the West Front, the doors slightly west of the center of the Nave that provide access to the Nave from the south and from the Nave to the North, through Paul’s Alley, and the massive doors in each of the North and South Transepts.

As far as measurements go, this data gives us a great deal to go on, except of course for the height of the ceiling inside the building. For this data, we returned to the unexpected source — shown above — of Christopher Wren’s scale drawing of the building showing its interior vertical dimensions.

Wren presumably would have left intact Jones’ tacking on classical columns and window treatments to the Norman Nave, but replaced the Cathedral’s truncated spire with a baroque dome, perhaps in imitation of, or envy of, the great dome of St Peter’s Basilica, in Rome, completed in 1590. Regardless of Wren’s plans, however, the Great Fire intervened in 1666 and Wren, on hand already, had the chance to redesign the entire building.

For our purposes, of course, what matters in Wren’s scale drawing is the dimensions of the vaulting, windows, and height of the ceiling. The Nave was about 263 feet from the West Front to the Crossing (where the Transepts intersect with the Nave and the Choir). The Nave was about 84 feet wide. The central aisle was about 42 feet wide, with each side aisle about 20 feet wide. Overhead, the internal crown of the vault of the nave was about 102 feet above the floor.

The Transepts were about 115 feet from the North Front to the South Front and were about 84 feet wide. The central aisle of each Transept was about 42 feet wide. Overhead, the internal crown of the vault of the Transepts was about 102 feet above the floor.

The Choir was 240 feet long and 84 feet wide, with the central aisle measuring 42 feet wide. The section of the Choir occupied by the Choir Stalls was about 33 to 35 feet long. Overhead, the height of the ceiling above the floor changed as one moved eastward. To get to the floor of the west end of the Choir from the Crossing, one had to climb a set of steps, a distance of about 12 feet. So the internal crown of the vault of the Choir above the heads of folks sitting or standing among the Choir Stalls was about 90 feet above the floor. To approach the Altar area, one had to ascend another set of steps, perhaps another 12 feet, so the internal crown of the vault of the Choir above the heads of folks standing or kneeling at the Altar was about 78 feet.

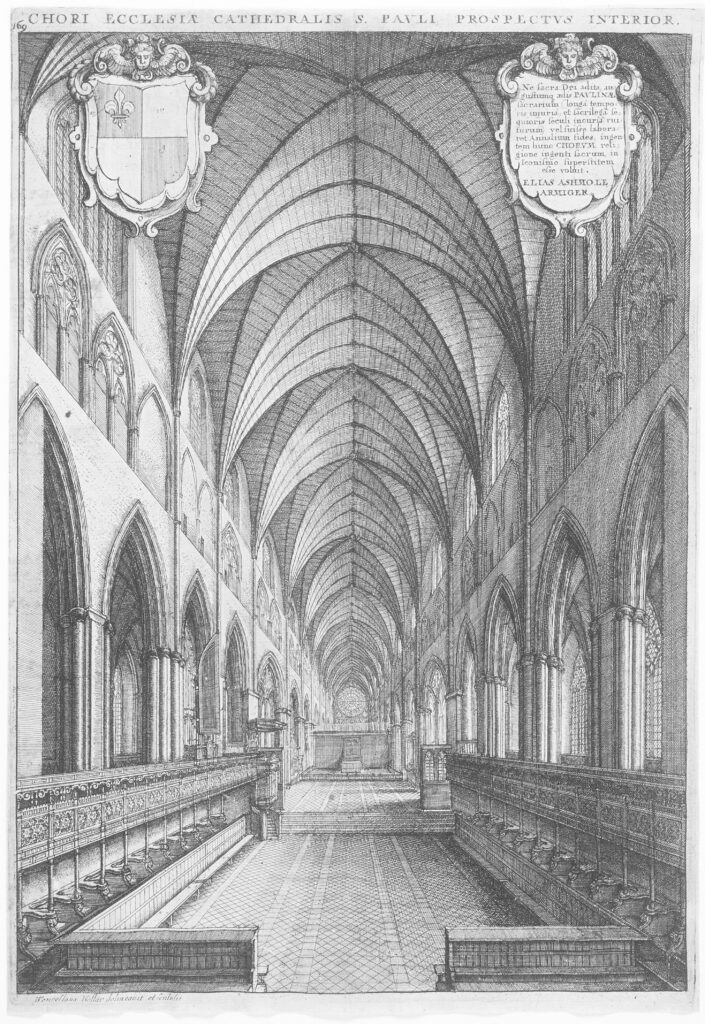

What we know about details of the interior of St Paul’s Cathedral is highly dependent on the set of engravings done by Wenceslas Hollar for William Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s Cathedral (1658), augmented, when possible by evidence drawn from the original building itself, based on construction stones that have been recovered since the Great Fire.

As discussed above, scholars have identified the basic design for the Nave of St Paul’s as that of the Church of Saint Etienne, in Caen, France.

Based on all the evidence, we began to create our model of the Nave by developing drawings such as these. The basic construction of the Nave was done by Carlos Lemos, of the Museum of London Archaeology. His work was incorporated into the larger model by Smith Marks, at NC State University.

The model developed, bay by bay, from the Crossing to the West Front.

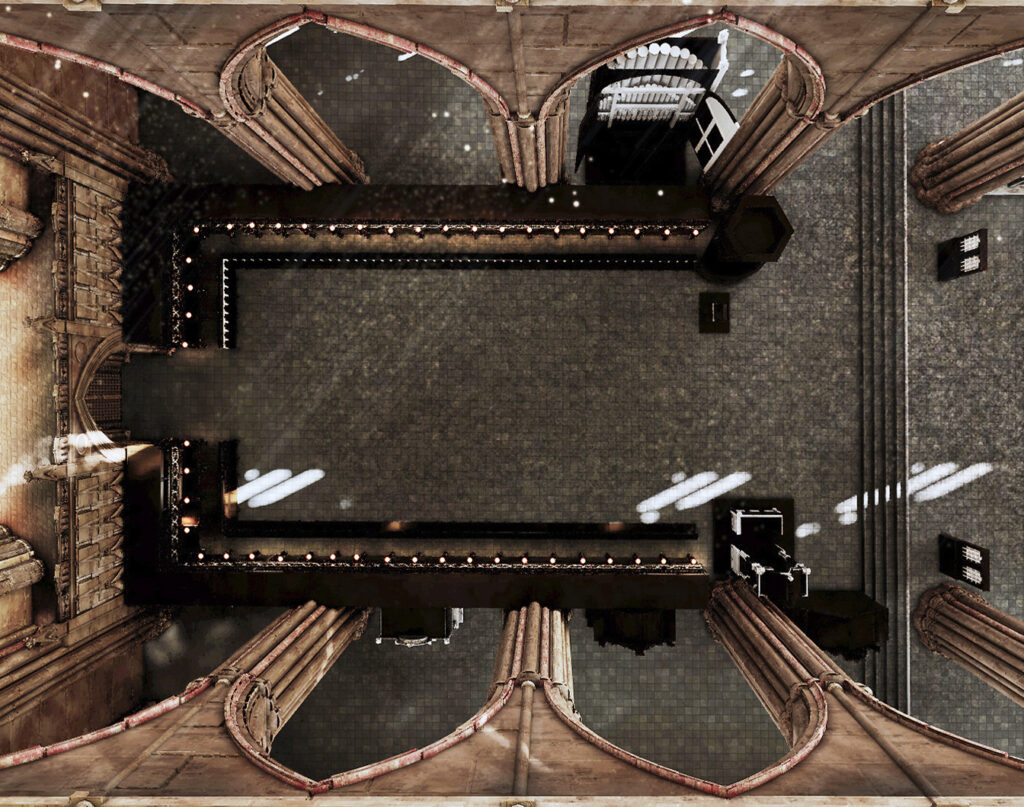

The rendering phase adds details of light and color and the effects of aging.

The Glass: St Paul’s Cathedral probably had an extensive program of stained glass prior to the Reformation. In creating the windows for our model, we chose to believe that — since London was a center of support for the Reformation — St Paul’s would have had this stained glass removed either during the reign of Edward VI or during the early years of Eliazabeth’s reign. We chose to model it with clear glass in the windows, following the argument of Richard Marks, although it is also possible that the glass might have been white, which would of course reduce the intensity of light coming through the windows.[3]Richard Marks, Stained Glass in England during the Middle Ages. Toronto, 1993, p. 324.

The Colors: Decisions about color were based on two sources. The red, orange, and yellow colors are based on the few fragments of painted stones which have come to us from the ruins of medieval St Paul’s. The blue and gold are taken from reconstructions of other great English and French churches, as established over time by scholars.

Some of the Cathedral images show especially the ribbing of the Cathedral ceiling glowing in a shade of blue or a shiny gold, neither of which was what we were working toward. The dull gold shown in other images is the goal we were trying to reach. The colors are deliberately faded and uneven in application as a way of suggesting ways in which the building might have manifested its need for repairs.

Hollar guided us as we look eastward from within the Nave. To turn around and look westward required turning Hollar’s image around and imagining how our model of the West Front would look from within.

Hollar does give us a view of the Choir Screen, see below.

Hollar’s image enabled us to imagine it, see the image below.

Above the Choir Screen was, of course, the Cathedral’s Tower, for which there is no surviving image from the inside, so we created this view, extrapolating the interior from Hollar’s exterior views of the Tower.

This is a good time to show an image of the entire ceiling, to link visually the Tower with the ceilings of the Nave and Choir.

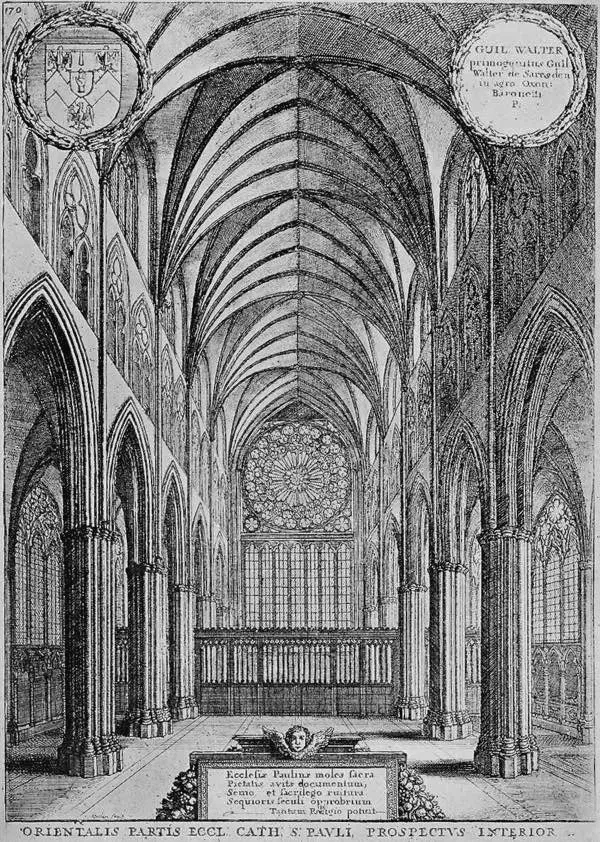

Hollar’s most important engraving for us is, of course, his image of the Cathedral’s Choir.

The details of Hollar’s image, while clearly delineated, are not unproblematic. The various elements of this depiction — the Stalls, the Pulpit, the the Organ, the Altar — are in their expected places. But we also know that when Hollar made this engraving in 1658, all this furniture had been removed previously by agents of Cromwell’s government. While it is possible that Hollar had seen the Cathedral’s Choir prior to the Civil War — some of his images of the Cathedral date from the 1630’s — he was, by the late 1650’s, chiefly working from memory.

One point that particularly concerned us was the number of Stalls in Hollar’s Choir, which seems to be limited almost completely to the number required for seating for all the Canons, or Prebends, of the Cathedral’s Chapter. There seem to be — in Hollar’s engraving — eleven seats on each side of the Choir, plus four running along the part of the Choir backed up against the Choir Screen, for a total of 30, the number of Prebends. There also seems to be open space for an additional 2 or 3 people on each side of the Choir, at the east end of the Stalls. So, according to Hollar, seating in the Stall area would accommodate 36 to 40 people. The benches running along the sides of the Choir provide additional seating, chiefly for the members of the Choir, which numbered 28 people, including 18 adults and 10 boys.

A recurrent theme of our work has been to understand the size and composition of worshippers at the Cathedral, especially the number of those attending John Donne’s sermons. The number of stalls as shown by Hollar meant that he was preaching to a congregation of about sixty people. There is evidence that on some occasions people who could not find seating in the Choir would have stood in the side aisles of the Choir, potentially accommodating a much larger group of worshippers. There is also the possibility that the top of the Choir Stalls could have provided additional seating.

Nonetheless, we explored what we believed was a more conventional seating plan, one visible in most if not all cathedrals today — multiple rows of banked seating as in the image below from Salisbury Cathedral, a “secular” cathedral, like St Paul’s, in the Middle Ages, “secular” because, unlike other medieval cathedrals in England, it had no monastic chapter associated with it.

This seating arrangement shows two rows of choir stalls on each side of the choir, plus a row of bench seating on each side, fronted by a long wooden stand to hold the Choristers’ music.

We were well into planning to create a similar seating plan for our model of St Paul’s until Advisory Committee member Gordon Higgot advised us that Westminster Abbey, in the late Middle Ages, had a seating plan almost identical to the plan Hollar shows for St Paul’s. So we decided to stick with Hollar in our model.

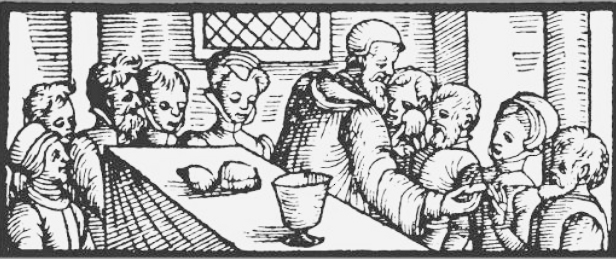

Between the Choir Stalls and the Cathedral’s Altar is an open space through which people coming up to the Altar to receive the bread and wine of communion would have had to pass. The priest celebrating Holy Communion is standing at the north end of the Altar, as he perhaps would have been.

The rubrics for the early Books of Common Prayer direct the Altar to be located away from the East Wall, where the high altar would have been located in the Medieval Cathedral. One alternative, in a space with Choir Stalls, would have been to have the Altar oriented east-west in the space between the Choir Stalls, with the Priest celebrating Holy Communion standing on the North Side, facing the communicants across the Altar as they kneeled at the Altar Rail, then going around the Altar to administer the bread and wine to them.

Administration of Communion in a parish church. Engraving c. 1580. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

In cathedrals, and in some parish churches, as time went by, the Altar was moved back to its traditional location, yet priests continued to stand at the North Side of the Altar, until sometime after the Restoration in 1660 they began facing eastward once more, with their backs to the congregation.

Hollar’s final contribution to the overall design of our Model is his image of the East End of the Cathedral.

From the position Hollar takes his image, behind us in the Medieval Cathedral would have been the Shrine of St Erkinwald; in front of us would have been St Mary’s Chapel. To the right of Our Lady’s Chapel would have been the Chapel of St Dunstan, while to the left would have been St George’s Chapel. The wooden screen across the central space and aisles could well have been part of the original medieval furnishings of 1313.

In our model, we essentially match Hollar’s image. For a more detailed walk around the Interior Model, check out the TAB labeled Interior Tour on the website.

The History of Reimagining the Interior

The images below are from Henry W Brewer’s set of engravings from the late 19th century, depicting his interpretation of Hollar’s engravings of St Paul’s interior.

Data Still to be Examined

Building our model has always been a work-in-progress. As we worked through the data available to us, we also from time to time became aware of sources of data with which we had previously been unaware. Some of this new information has been incorporated into the model. Other sources, however, came to our attention too late to be included. We also believe there is material yet to be found, all of which will shed further light on the structures inside Paul’s Churchyard.

Please see the material under the tab “Future Work in Modeling” for a discussion of sources of information of which we are aware but were unable to take advantage of, due to limits on our available time, staff, and money. We encourage scholars and students to criticize our models and methods, and to contact us with suggestions for improvement. While the Project has no funds currently available for further work, we will store the comments for eventual use. See the FEEDBACK page below the OVERVIEW tab for contact information.

References

| ↑1 | For a discussion of the design and construction of St Paul’s in the context of other English and continental cathedrals, see Christopher Wilson, The Gothic Cathedral (London, 1990). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Bookshops in Paul’s Cross Churchyard (London: Bibliographical Society, 1990. |

| ↑3 | Richard Marks, Stained Glass in England during the Middle Ages. Toronto, 1993, p. 324. |