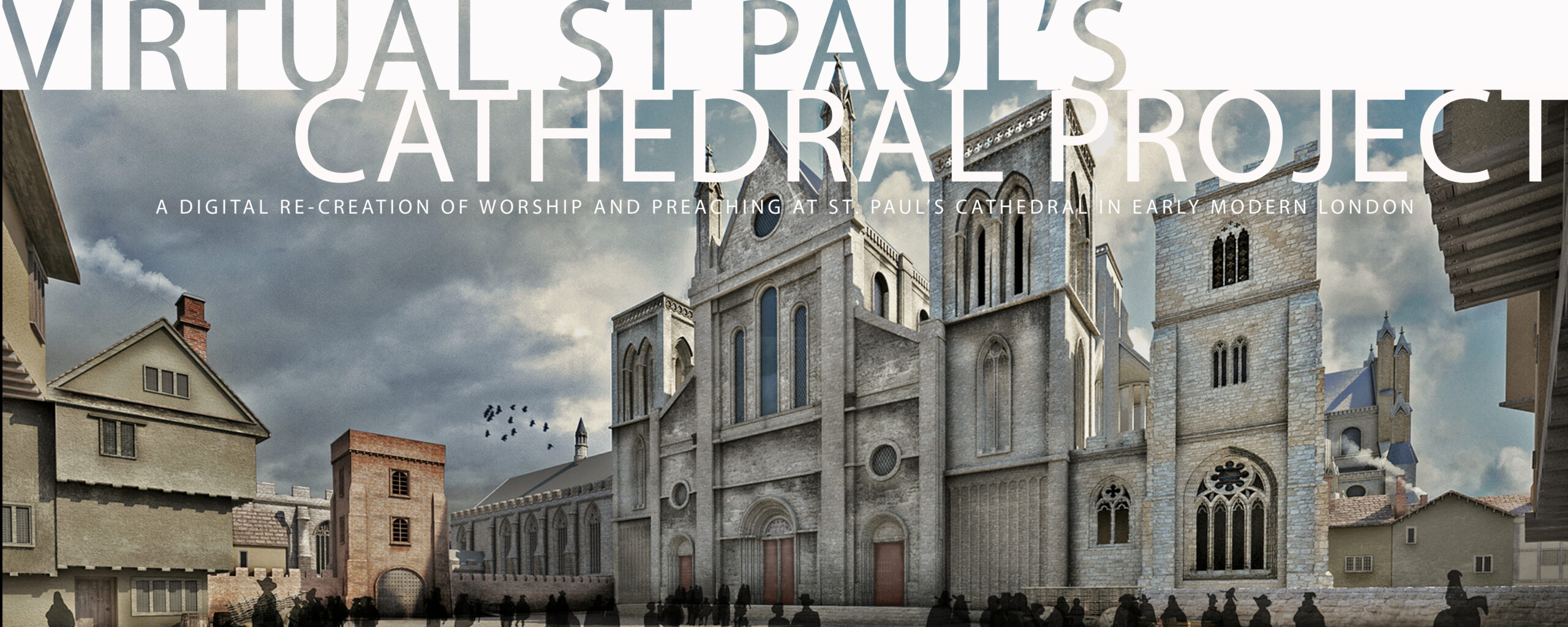

The Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project enables us to experience the sounds of worship in London’s St Paul’s Cathedral in the 1620’s, even though the building itself was destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Our ability to hear sounds recorded in the present as though we were hearing them in physical locations now inaccessible to us is dependent on two processes.

The first is our ability to model electronically the acoustic properties of lost spaces. An acoustic model provides the basic geometry of a space, along with the the acoustic properties of the materials used in the construction of that space.

Sound, once emitted, behaves in predictable ways. If the space in which the sound is heard is an open space, then the sound attenuates over time at a predictable rate as it moves through space. So, the further the hearer is from the sound source, the quieter the sound relative to the volume of the sound at the moment of emission.

If the space is confined by natural or architectural features, the geometry of the space and the composition of the surfaces in the space affect the transmission of sound. Sound, when it encounters an object, is either transmitted, reflected, or absorbed to a greater or lesser degree, depending on the size, shape, and physical characteristics of the materials that make of the surface of objects in the path of the sound waves.

The second is our ability to create recordings of sounds that include only the emitted sound itself, eliminating or minimizing effects of the properties of the spaces in which the sound was recorded. These recordings are called “dry” recordings, as opposed to “wet” recordings, which include both emitted and reflected sound, enabling us to hear the resonances and reverberations of the specific spaces in which the sound was recorded.

The driest of dry recordings are made in anechoic chambers, recording studios whose walls and floor are made of thick, highly absorbent materials. “Anechoic” literally means “without echo”; Ben Crystal’s recording of Donne’s Gunpowder Day sermon for the Virtual Paul’s Cross Project was made in an anechoic chamber at Salford University, in Manchester, England.

Anechoic chambers are best used by solo performers. Ensembles can make recordings in anechoic chambers but only by performing the composition over and over, with one member of the ensemble performing in the anechoic chamber at a time. The rest of the ensemble performs in another space; all the performers are linked to each other electronically so they can all still play together. The final recording consists of a compilation of all the performances made in the anechoic chamber.

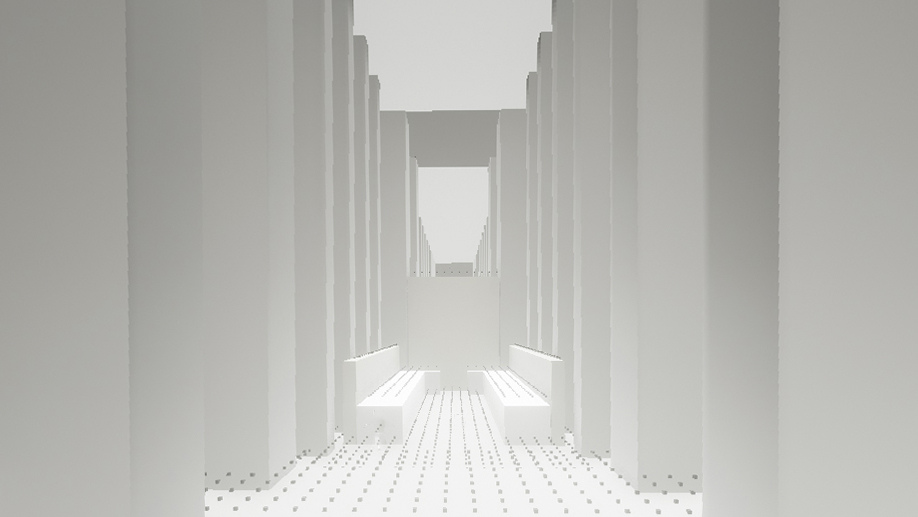

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir, from the Pulpit. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Given the the fact that the Choir of Jesus College, which stood in for the Choir of St Paul’s Cathedral, consists of 22 members, if we had chosen to use an anechoic chamber for our recordings, each of the compositions performed by the Choir would have had to be recorded at least 22 times. This would have been prohibitively expensive for the budget of the Cathedral Project.

Fortunately, recordings sufficiently dry for use in an auralization project can also be made in a more conventional studio by combining a number of recording equipment and techniques. These include the use of sound-deadening material on the surfaces of the studio as well as individual highly directional microphones for each sound source. Directional microphones shield out ambient noise and pick up only sounds produced by the source right in front of them, by, for example, a person speaking or singing.

For the Virtual St Paul’s Cathedral Project, this technique was used for all recordings. The bulk of the recordings, including all recordings by the Jesus College Choir as well as by the actors Colin Hurley, David Crystal, and William Sutton were recorded in the West Road Recording Studio in Cambridge University’s Centre for Music and Science.

The recording engineer Matthew Dilley, of About Sound, organized the recording sessions; the recording engineer Daniel Halford conducted the recordings.

St Paul’s Cathedral, the Choir, from the Dean’s Stall. From the Visual Model, rendered by Austin Corriher.

Ben Crystal’s recording of John Donne’s Easter Day sermon and other material were made at the Sans Walk Studio in London. Matthew Dilley was the recording engineer.

The part of the crowd disporting itself in Paul’s Walk (ie the Nave of St Paul’s Cathedral) was played by members of the faculty in linguistics and their graduate students at NC State University, gathered in Post Pro Studio in Raleigh, NC, with technical support provided by Matthew Horton, acoustic engineer.

In Raleigh, the work of organizing the files into usable material was completed by Neal Hutcheson, our colleague in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences and an Emmy Award-winning documentarian and film-maker.

Grey Isley (see more above on Grey’s role in ths Project) created the Acoustic Model.

Seth Hollandsworth, a student in computer science and mechanical engineering at NC State University, carried out the auralization process under the supervision of acoustic engineer Dr. Yun Jing .